21 rue la Boétie – Musée Maillol, Paris

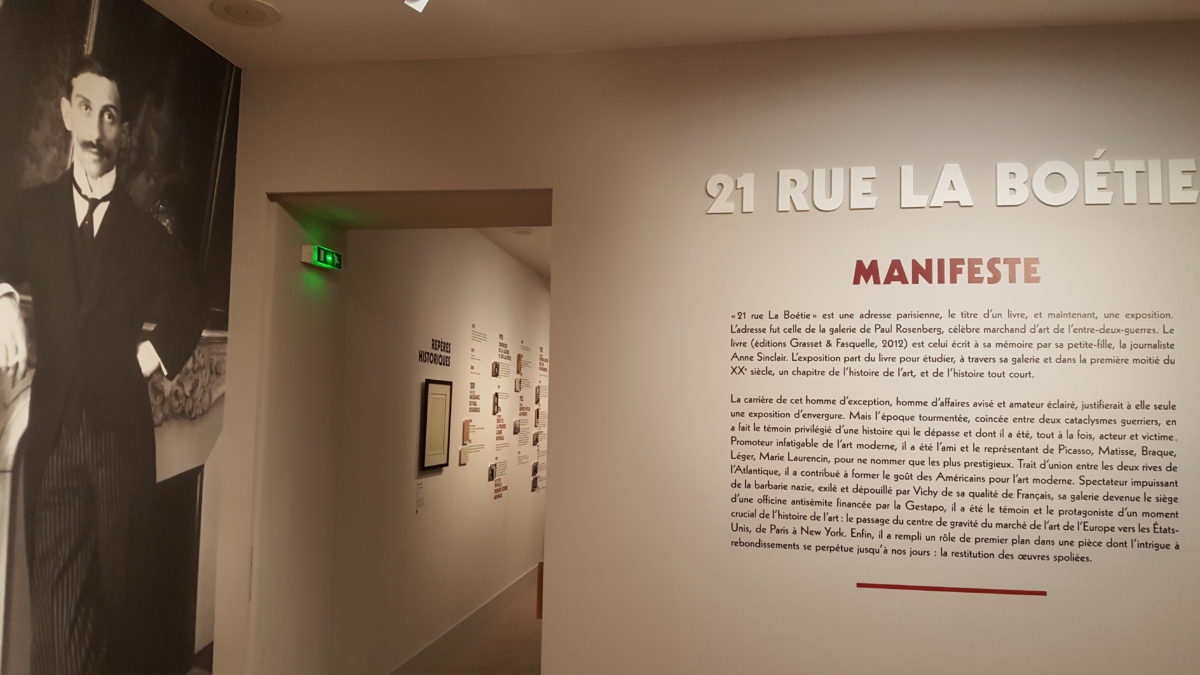

This is an exhibition with a very good starting point: a successful and creative businessman, buffeted by the vagaries of 20th Century history, whose story illustrates a much wider narrative. Plus that of a granddaughter (Anne Sinclair), public figure, painted by major artists as a child, and now author of a successful history of her grandfather’s life and gallery. The strength of 21 rue la Boétie is the way that the narrative move so easily from the small to the large, from the intimate family history to the crashing waves of discrimination, spoliation and exile. The drawback, at least to my mind, is where the waves become too large, and overwhelm the personal story.

Paul Rosenberg admittedly had a head start in becoming an influential figure in the art world. His father before him was an art dealer, and from him Paul inherited a stock of impressionist works as well as impressive contacts. Paul did not rest on these family laurels, however, but showed himself to be forward-thinking and savvy, making his clients feel safe in investing in modern art, developing strong relationships with artists such as Picasso, Braque, Léger and Laurencin, and committing to an aggressive output of exhibitions supported by all the modern techniques: catalogues, adverts, etc. He saw the potential of the American market early on, which was to prove fortunate later in life.

When life caught up with Paul Rosenberg, he was at the top of his game. Catch up with him it certainly did, however, and he ended up stripped of his French citizenship and in exile, with some of his works and archives intact, but with many others seized, and the gallery itself turned over to an ‘Instutute for the Study of Jewish Questions’. The American network he had built up now came in handy in reestablishing his gallery and career, and in fact Rosenberg was influential in the shift of the art world’s centre of gravity from Paris to New York in the post-war period. Rosenberg, like many others, fought to relocate and recover his property, but this is always easier said than done, and remains an ongoing project for his heirs.

So far so good as far as an interesting life story which neatly illustrates wider historical forces is concerned. The next question to which we must address ourselves is how the curatorial team (Belgian company Tempora) have made use of this to construct an exhibition. Firstly it should be noted that this is not the exhibition’s only location. First mounted in Liège, it will travel elsewhere once its time in Paris is finished. To me, however, the way in which space was geographically divided within the Musée Maillol between the portrait of the gallerist and his world upstairs and the wider historical narrative downstairs, reinforced what I saw to be the strengths and weaknesses of the approach.

The upstairs section I enjoyed immensely. Rich with works by major artists, many of which passed through the gallery and many from private collections, it also draws on period photographs and archival materials to create a picture not just of Rosenberg himself, but of the way in which the work of a good dealer is so important in shaping tastes and therefore prices and the art history canon itself. The strong relationship between Rosenberg and his inner circle of artists is reinforced by the portraits of himself and his family, which are often touching in their intimacy. Also very interesting is the way in which Rosenberg exhibited new artists alongside more established impressionists and post-impressionists to inspire confidence in his choices, here represented by Toulouse-Lautrec among others.

Moving downstairs, I found it harder to follow the thread of historical forces told through personal narrative. The scope widens in the second half of the exhibition to include degenerate vs. realist art, and Nazi expropriation, exhibitions and sales. Undoubtedly Rosenberg and his family were affected by these events, but I found the personal narrative of the first section to be somewhat diluted here. It becomes clearer again in the final sections on Rosenberg’s new life and influence in New York and on the restitution of spoilated works: a favourite topic of mine and neatly demonstrated by the life history of Matisse’s ‘Profil bleu devant la cheminée’, which was returned to the family in 2014 and subsequently sold at auction. Here again the sense of personality and of one man’s place in (art)history returns.

It’s undoubtedly a very good exhibition: engaging, interesting, thoughtful and respectful of Sinclair’s work and her relationship to the subject matter. I did find the middle section slightly weaker at the point that its scope was the widest, but would still encourage anyone with an interest in 20th Century history and art to go and see it. A note: the exhibition texts are only in French, so those of you who ne parlent pas français may be aiming for more of an immersive experience than an educational one.

Until 23 July