The Covid Diaries 88 – Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge

A review of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA) in Cambridge, including their exhibition [Re:] Entanglements: Colonial collections in decolonial times. A pleasant and forward-looking museum, perfect to get a flavour of Cambridge’s university museums.

MAA Cambridge

We are now most of the way through the Salterton Arts Review’s outing to Cambridgeshire. Today is my final Cambridge museum post, and the next post will be a daytrip to Ely. The University seems to manage pretty much all of the museums in Cambridge. See, for example, Kettle’s Yard and the Fitzwilliam. Nonetheless, some are what I would consider ‘proper’ university museums – ones which started as educational resources for students studying particular subjects. I’m talking about things like the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences and the University Museum of Zoology.

The Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology is one such museum. It started life in 1884 as the Museum of General and Local Archaeology. The collection continued to expand through donations and fieldwork and the museum moved to purpose-built premises in 1913. Today there is a charming display of archaeological and anthropological materials over two floors (one a mezzanine, so essentially one large space). Temporary exhibitions and local archaeology occupy a separate ground floor space. Let’s have a look in a bit more detail at what’s on offer, including a temporary exhibition which I loved.

MAA – Not An Encyclopedic Museum…

Given my enthusiasm for ‘old-fashioned‘ museums, I found the MAA rather charming. The majority of the collection is in the two-story space with a mezzanine, grouped more or less by culture. There are objects from Oceania, South America, Asia and other corners of the globe. There is also, slightly incongruously, an Inigo Jones choir screen salvaged from Winchester Cathedral.

The collection feels a little eclectic. I suppose this is because a lot of it has come either from donations, or from field work. So it’s not trying to be a comprehensive museum or either archaeology or anthropology. Rather, its trying to display well the objects it happens to have ended up with. The text panels accompanying objects are generally quite simple, but give interesting background information that it would be impossible to glean just from looking.

…But A Forward-Thinking One

So the collections and overall display at MAA may be a little old-fashioned (charmingly so). But the museum’s attitudes to the objects in its care seems to be rather forward-thinking. They have done a few simple things which I liked, and which help to ensure relevance despite some of the challenges these days with anthropological/ethnographic museums. These were:

- Visible storage – ie. getting as much out on display as possible. Even where this means revealing some of the ‘behind the scenes’ aspects.

- Contemporary commissions – there were quite a few of these, responding to or incorporating objects in the collection. This is a good way to engage with contemporary source communities and bring diverse voices into the museum space.

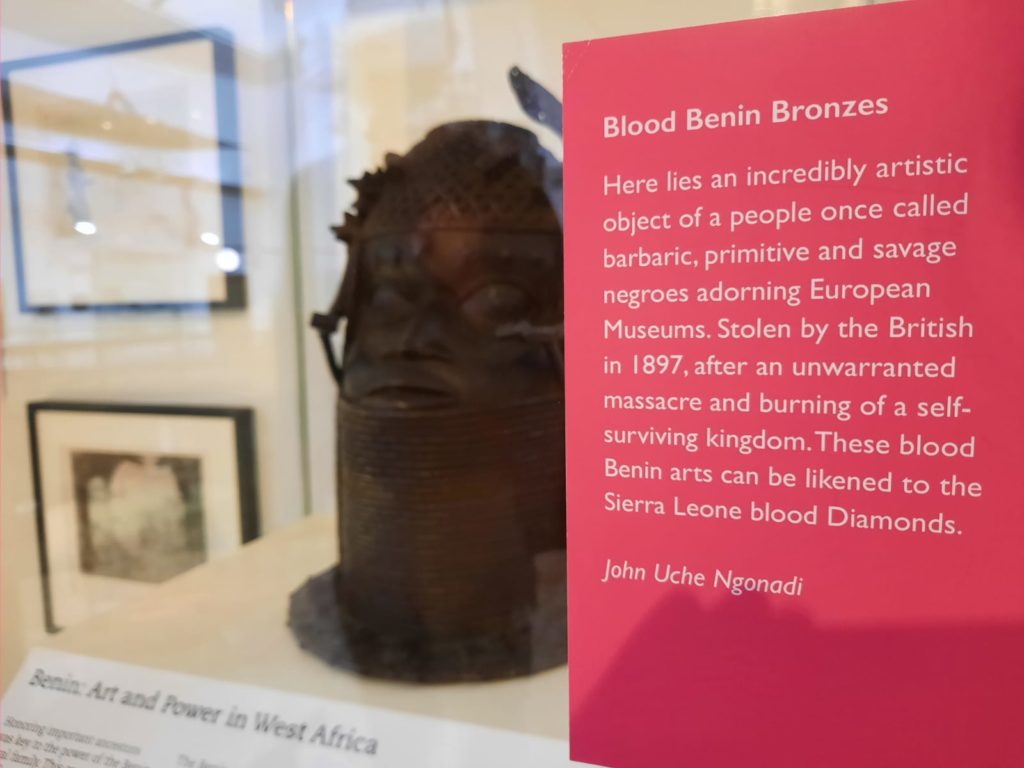

- Confronting the Benin Bronzes issue. These magnificent works were looted over a century ago after an unjust conflict. The tide seems to be turning in favour of return to Nigeria, and the MAA is very transparent about its approach.

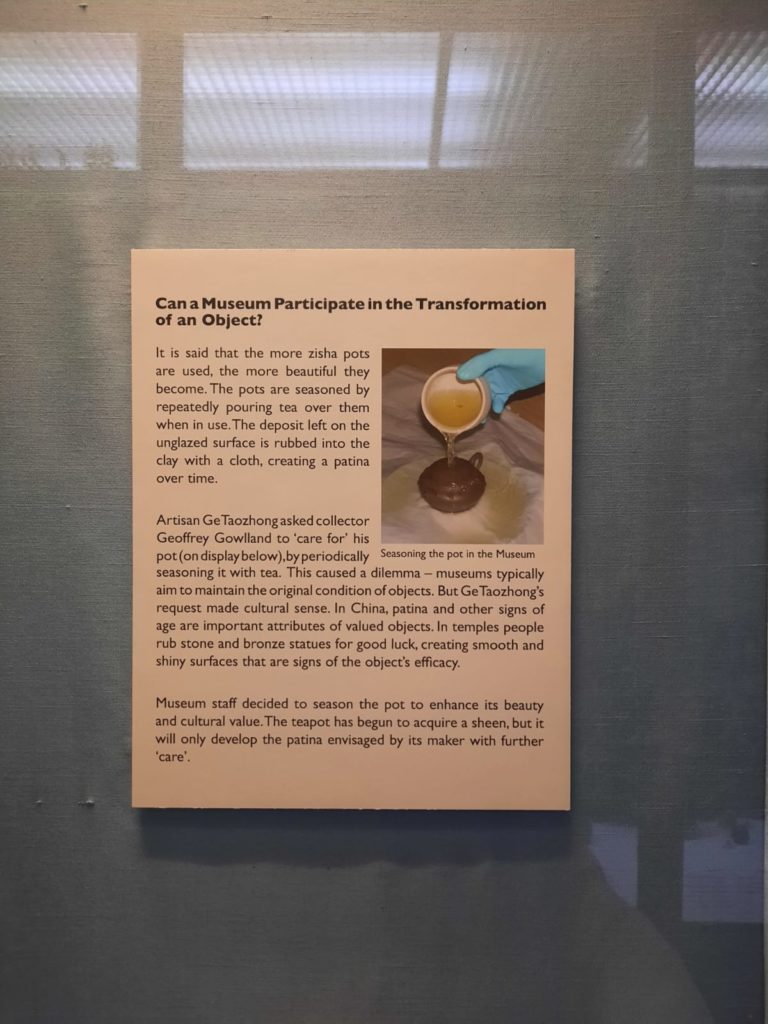

- Being up front about choices. Anthropological or ethnographic museums constantly face decisions about collections care. Should they preserve the objects in a static way like the Western museum tradition asks, or should they treat the objects as source communities would have treated them (eg. allowing them to disintegrate, refreshing decoration regularly, not displaying them in certain contexts, etc.)? In the images above there are two examples of where the MAA has made a choice to intervene, and clearly explains this, as well as the reason behind it. A teapot, for example, has been ‘seasoned’ with hot tea so that it becomes more beautiful. A descendant of the carver of a Maori flagpole (pouhaki) has restored it, to honour and celebrate his great-great-grandfather’s skill. Collections care standards are not pre-ordained, so I liked this up front approach.

[Re]: Entanglements – Colonial Collections In Decolonial Times

This ground floor exhibition was the final thing I saw at MAA, and I LOVED it. It was right up my street – tackling difficult questions about collections and exhibition ethics, and how we should view historic collections today. The subject of [Re]: Entanglements is the collection of African objects and archives amassed by Northcote Thomas, a Cambridge alumnus and ‘Britain’s first colonial anthropologist.’

Thomas assembled an ‘ethnographic archive’ between 1909 and 1915, collecting from peoples in Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone. He collected ‘masks, drums, carved wooden figures and staffs, pottery, textiles, charms, dolls, photographs, sound recordings, botanical specimens, published work and field notes.’ This was very much within a colonial context and power structure, but what is interesting is that the colonial authorities did not support Thomas’s project. Or rather, the Colonial Office in London was initially supportive, but local colonial governments in West Africa thought he was interfering. He was sympathetic to local communities and leaders, and was forthright in telling colonial authorities his views. Eventually the project became too expensive, and Thomas had not been making himself popular, so it ended.

Thomas mistakenly believed to begin with that the British Museum would acquire his collection. They didn’t want it, but the MAA took it on, although different sections are today dispersed (sound recordings to the British Library, seeds to Kew, etc.). The MAA continues to hold part of the collection today, but this is its first display as a distinct collection.

A Complex Legacy

[Re]: Entanglements looks at the legacy of Thomas and his collection. How should we understand the circumstances of collection of these objects, photographs, stories, plants, etc.? And what do they mean to us today? They are not easy questions to answer.

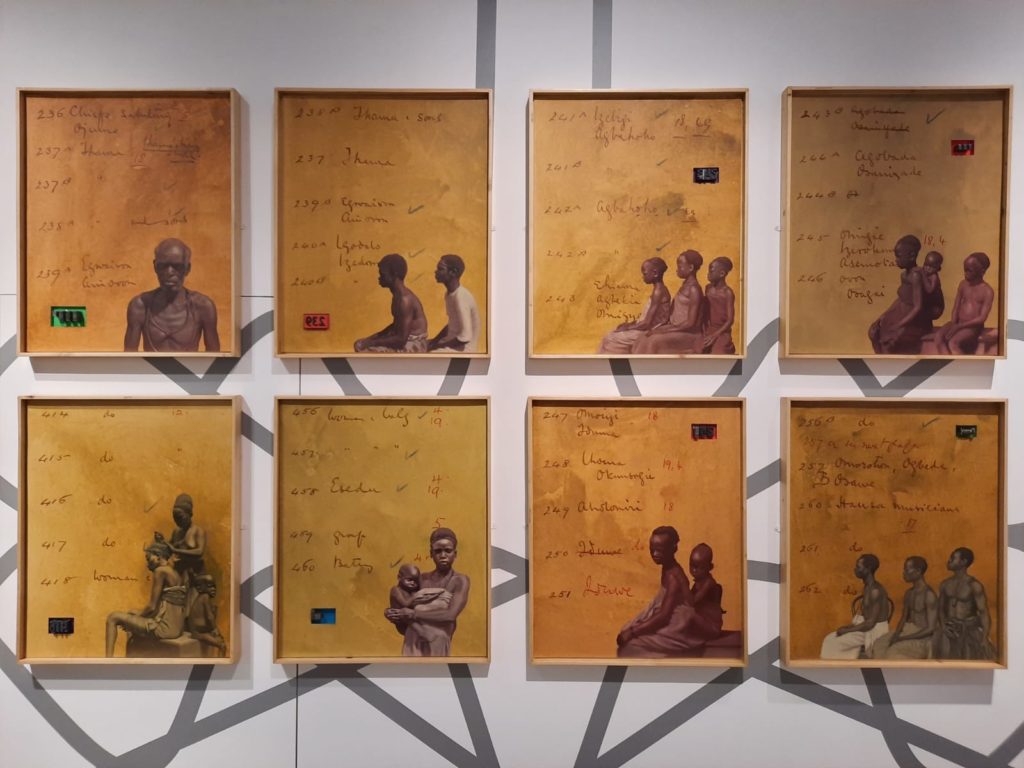

Thomas’s multi-disciplinary approach means that this is a pretty rich archive. At the same time, his approach was probably grounded in some eugenics thinking: hugely problematic. So we are left with photographs rooted in racism as ethnographic ‘types’, and yet wonderfully rich, with great meaning to descendants today (Thomas collected enough biographical detail that often the subjects’ families can be traced). Likewise, we often hear about collection and restitution in terms of looting (like the Benin Bronzes above). These are not looted objects – most were purchases. But the power dynamics in which those transactions took place were hugely unequal. What does (or should) that mean for us today?

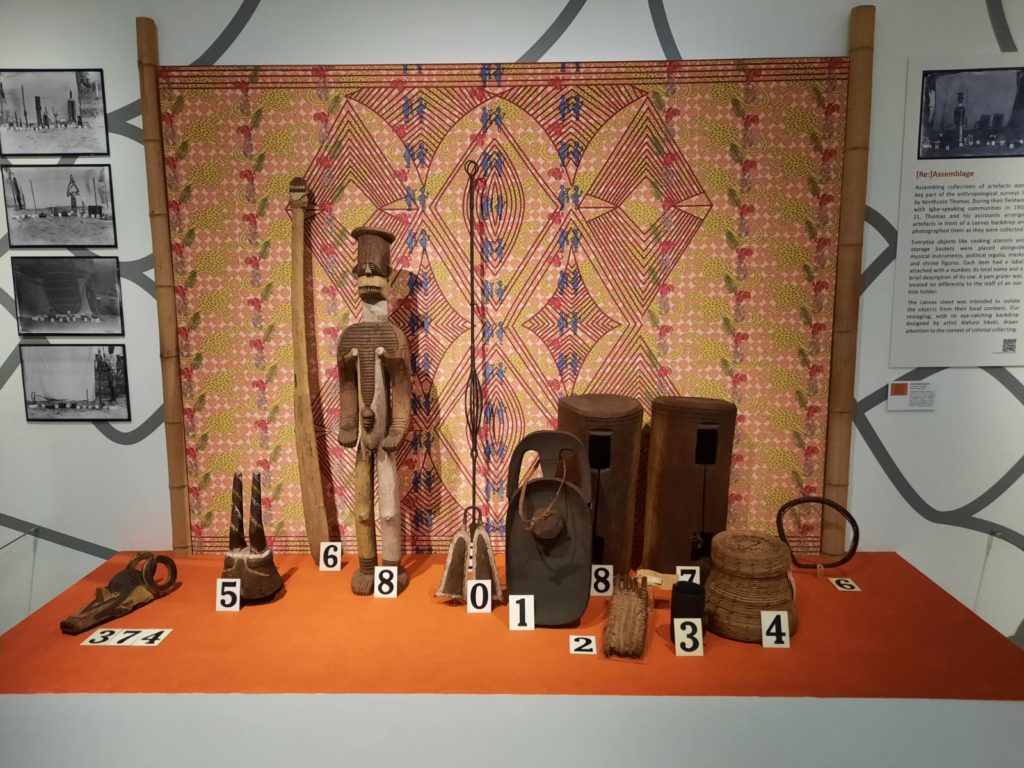

To explore these questions, makers and artists from Africa and the diaspora in the UK have created contemporary responses to Thomas’s collections. There are videos and photos as well as installation works, for example displaying a group of objects as Thomas did for photography, only with a textile by Alafuro Sikoki rather than the neutral white of the ‘scientific’ colonial approach. Many of the artists have focused on the way that the act of collecting has damaged as well as preserved.

It is really a wonderful exhibition. In today’s polarised world we need encouragement like this to live in the grey areas – not to dismiss or defend colonial projects, but to understand them and reinterpret them for ourselves here and now. If you can’t get to Cambridge right now, check out this exhibition webpage.

On its own merits: 3/5

[Re]: Entanglements: 5/5

Implementing Covid rules: 4/5

[Re]: Entanglements on until 17 April 2022

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

What might be the curator’s rationale for focusing on displaying the objects they “happen to have ended up with” rather than pursuing a more curated or thematic collection?