Poussin And The Dance – National Gallery, London

A review of Poussin and the Dance at the National Gallery. This academic exhibition about an academic French painter is pleasant and informative. Best treated as a little break from the outside world.

Poussin And The Dance

I am a big-time art and museum nerd, so I rather enjoyed the sound of this exhibition. I wasn’t previously very knowledgeable about Nicolas Poussin. I’ve spent enough time in Paris to know he’s an important painter in an art historical sense; painted in an academic style (vs. the Baroque which then prevailed), drawing on classical history; and is generally thought of as more serious than fun. Basically someone who would be top of the class but probably not invited to the parties.

This exhibition at the National Gallery tries to rehabilitate Poussin’s dour reputation somewhat. It does this by focusing in on a particular point in Poussin’s career. A a young man, Poussin was a painter from Normandy who had made it as far as Paris, but was obsessed with getting to Rome. At that time, Rome was the pinnacle of art, and Poussin wanted the chance to see classical antiquities for himself and learn from the best. When he arrived there in 1624 (aged around 29) he was in art nerd heaven. He went and studied all the best antiquities, rigorously sketching and measuring and so on.

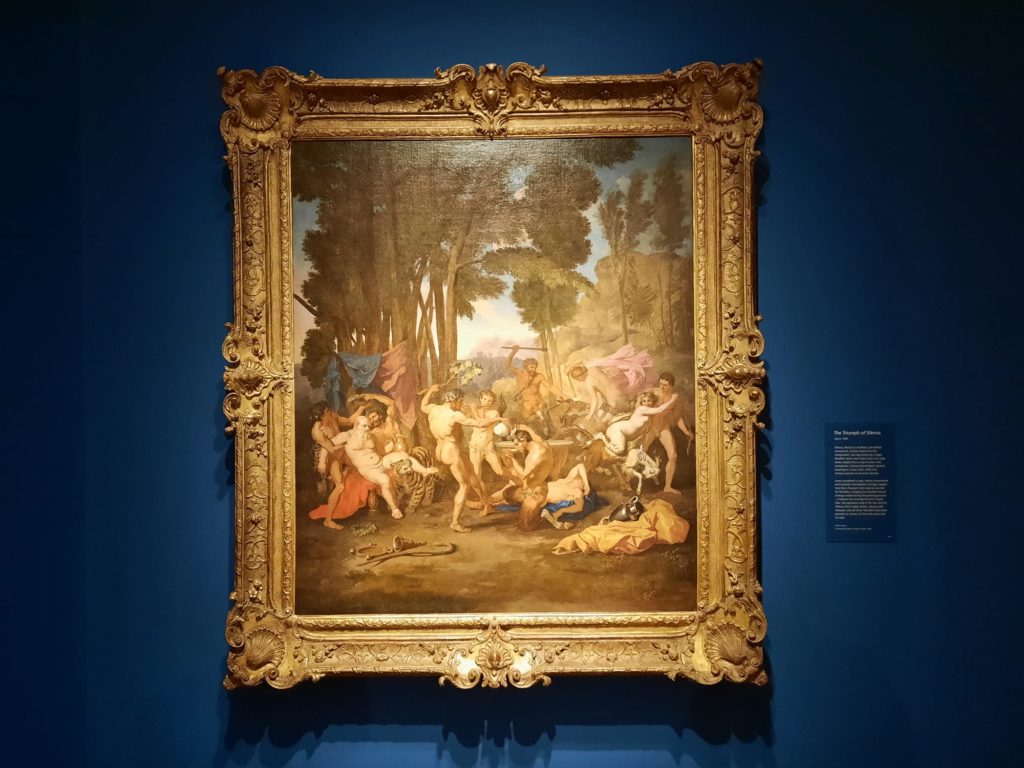

Poussin turned this source material into wonderful paintings, many of which brim with life and energy and, in particular, dancing figures. Curator Francesca Whitlum-Cooper is a Poussin fan, and has brought together works in which joy and movement are at the forefront, rather than serious art-geekery. Underlying all of this is the fact that the National Gallery has particularly good holdings of Poussin works and would like them to be better known, but there are several good loans on view as well, including ones from the Wallace Collection and museums in the US.

Getting To Know Poussin

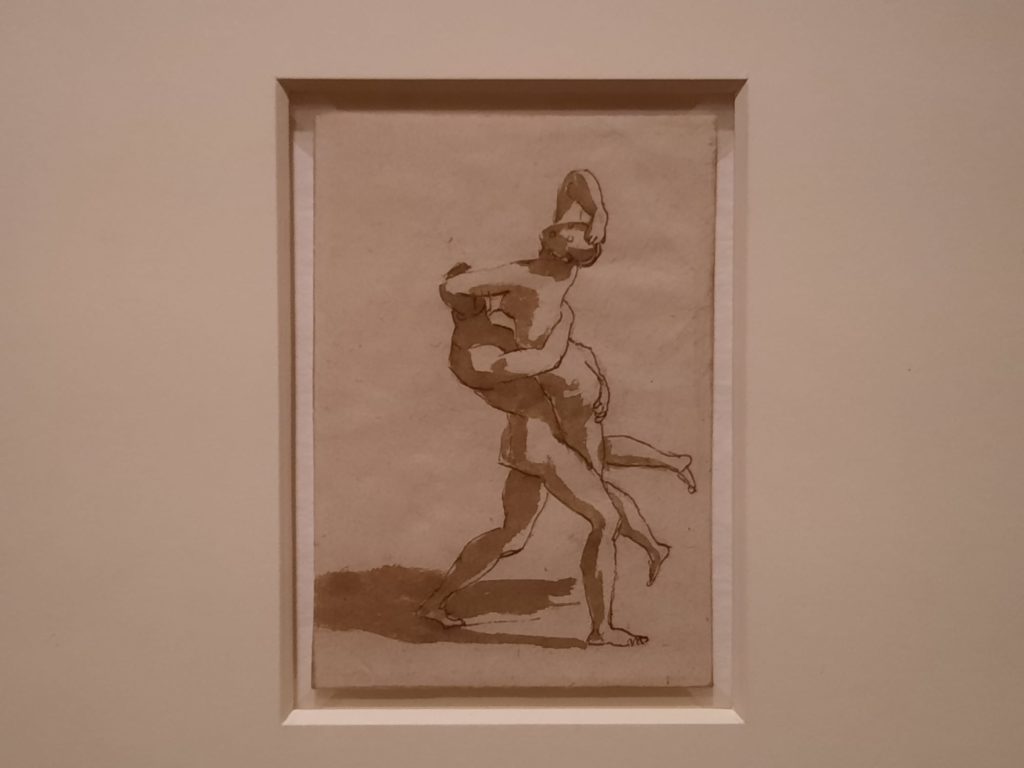

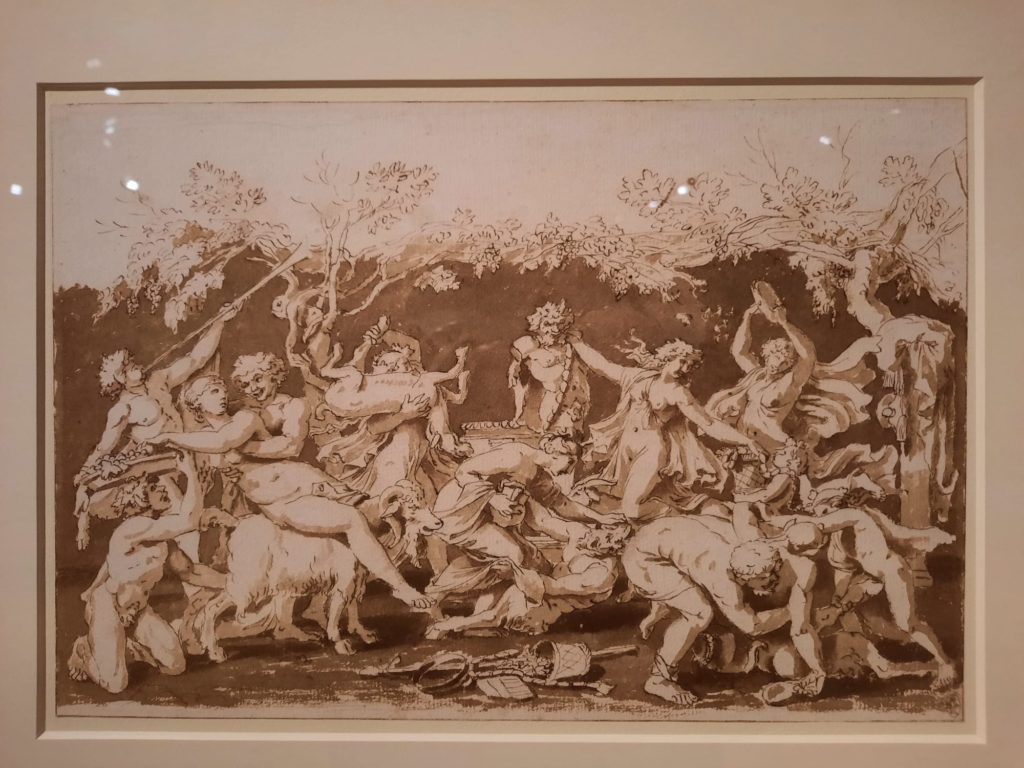

Poussin and the Dance is a nice, small exhibition. There are a few rooms to cover, but the paintings, sketches and objects are well-presented, and given space so visitors can properly contemplate them. There is a video to watch, and the National Gallery have also commissioned small wax sculptures from Andrew Lacey and Siân Lewis. More on those shortly. For an exhibition which aims to introduce and simultaneously rehabilitate an artist and his reputation, there isn’t actually that much detailed information. We get a brief introduction – he was from Normandy, he loved Rome, etc., but the texts are fairly short and to the point. Everything which is on view is also complementary; the sketches illustrate a point made about the paintings, or we can see an ancient sculpture translated into Poussin’s art.

The result is that the visitor feels almost fast-tracked. The points the curator makes are so clear and well-evidenced that there’s really very little room for doubt. The antiquities, in particular, are such great loans that we can see with our own eyes how Poussin translated figures from stone to paint. There is so much joy in the works on view that it’s probably more difficult to see why he has such a serious reputation in the first place.

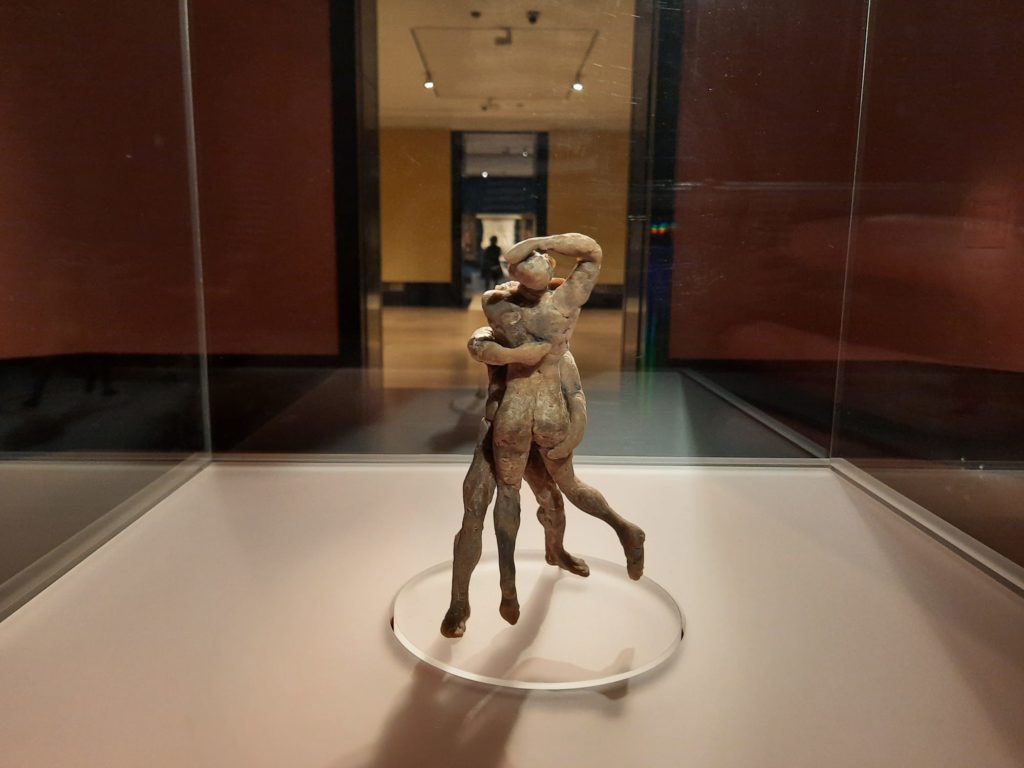

The second point the exhibition makes is about the way that Poussin worked. This is where the wax figures come in. we have evidence that Poussin modelled little figures in wax; he would sketch them and play around with different positions as part of his creative process. None of Poussin’s originals have survived, but the National Gallery have commissioned Lacey and Lewis to recreate a few. Looking from the new wax figures to Poussin’s original sketches, it’s so obvious that this is what he was sketching. It’s a great insight into how he was able to paint such complex groups of figures with such skill.

Experiencing The Exhibition

As I described above, this is a well-spaced and planned exhibition, with great loans. It was also an interesting compare-and-contrast exercise with other National Gallery exhibitions I have seen. This is the first paid exhibition here since the pandemic where I wasn’t uncomfortable with the visitor numbers. What I don’t know is whether this is because of the academic subject matter, or because I chose an early morning time slot. It was welcome either way, compared with my experience of Artemisia or Titian: Love, Desire, Death. A similarity with Artemisia, on the other hand, was the fact that the only two things in Poussin and the Dance that you’re not allowed to photograph are the first two you come across. I don’t know why that keeps happening – it basically keeps a member of staff busy full-time explaining the rules to people.

But anyway, these are minor details. There are three particularly good loans amongst the antiquities: the Borghese Dancers, the Gaeta Vase (no photos!) and the Borghese Vase. Seeing the specific objects from which Poussin drew his inspiration was a special treat. In terms of works by Poussin himself, the exhibition built to a crescendo. The penultimate room displays the Borghese vase alongside a series of three works Poussin painted for Cardinal Richelieu. Today they are respectively in the National Gallery collection and that of a museum in Kansas City, Missouri; again I relished the opportunity to see them in the flesh.

The final room showcases A Dance to the Music of Time, a loan from the Wallace Collection. You have to be a bit of a museum nerd to know how special this loan is; it’s only in the last couple of years that loans from the Wallace Collection have been possible at all. And so really the exhibition ends as it begins – an exhibition for exhibition lovers on a specialist art history subject. I love the National Gallery for this, and enjoyed my time exploring Poussin and the Dance.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Poussin and the Dance on until 2 January 2022

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

2 thoughts on “Poussin And The Dance – National Gallery, London”