Fighting Talk: One Boy’s Journey From Abandonment to Trafalgar – Foundling Museum, London

A review of the Foundling Museum’s exhibition Fighting Talk, a unique opportunity to hear a Foundling’s life story in his own words. From Foundling Hospital to the Battle of Trafalgar to a place as a Greenwich Pensioner, George King’s life reads like an adventure story.

Back at the Foundling Museum

It has been a while since we found ourselves here! The Foundling Museum was one of the first which I visited after the first lockdown. At that time I was very keen to see places that I had been complacent about before the pandemic and hadn’t seen despite more than a decade living in London. The Foundling Museum is a relatively small London museum, but packed with interesting and unique exhibits. You can read a lot more about that earlier trip here.

This time I was back specifically to see their temporary exhibition Fighting Talk: One Boy’s Journey From Abandonment to Trafalgar. This is the second insightful temporary exhibition I have seen at the Foundling Museum. On my previous visit, Portraying Pregnancy was on view, and looked at the changing ways that English society has viewed pregnancy and pregnant women over the centuries. This time around it was a much more personal exhibition, making use of a first-hand account of the life of George King.

I couldn’t help taking another look around the permanent exhibitions as well, so you can read more about that at the end of this post. But first, let’s get stuck into Fighting Talk!

Fighting Talk: One Boy’s Journey From Abandonment to Trafalgar

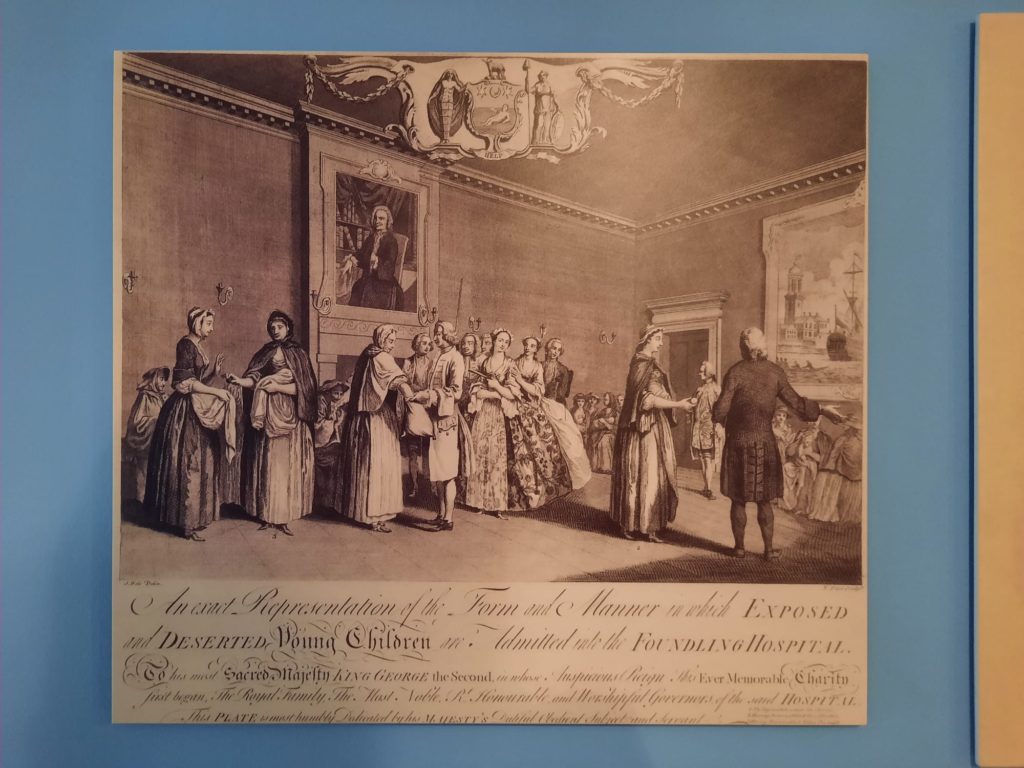

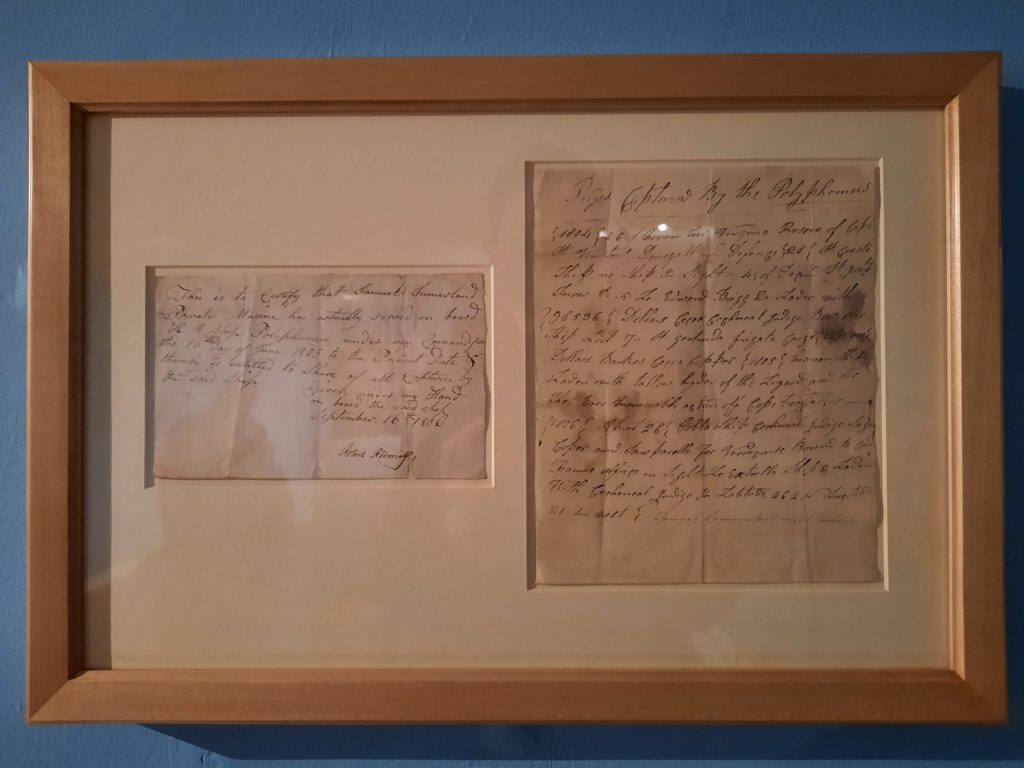

Who was George King, and why do we know so much about him? Firstly, George King didn’t start out as George King. He was born to an unmarried mother, Mary Miller, who successfully petitioned to have him admitted to the Foundling Hospital in 1787. This was a real palaver at the time. Mothers had to explain why they had fallen on hard times and how they would make use of a second chance. And provide character references. Even then they only got a spot at a ballot, where a white ball meant the baby was in (pending health checks), a black one meant it was out, and a red one meant maybe. The top image above is of one such ballot, and the second image shows Mary’s petition.

The outcome of all this is that Mary’s baby was accepted. Babies were always christened with a new name, however, to give them a fresh start in life. George’s name is in honour of the reigning monarch, George III. He is luckier than many Foundlings in that he not only survived his early childhood, he had a happy one thanks to his wet nurse/foster mother Anne Yeulet. Aged five, he then went back to the Foundling Hospital, where something very important happened: he received an education. Being a working class person able to read and write came in useful time and again throughout his life.

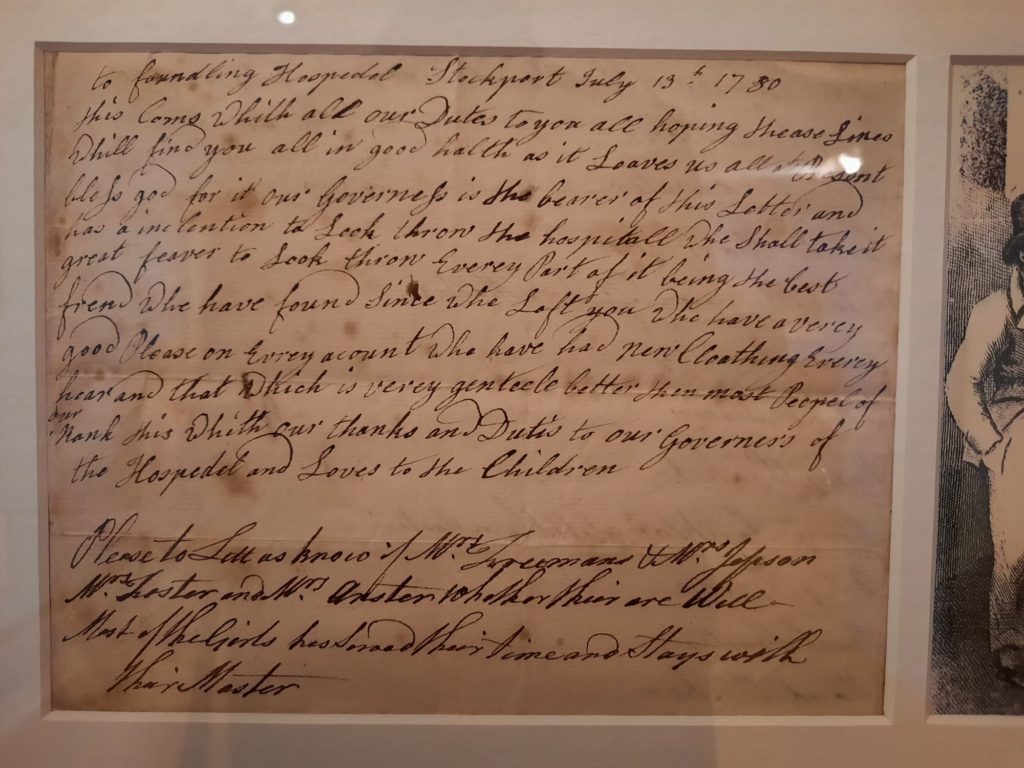

In fact, the education of Foundlings in reading, writing and arithmetic has led to a particularly rich archive. For example, most Foundlings were apprenticed out as teenagers, sometimes with mixed results. The fifth image above shows a letter from some girls removed from an abusive textile manufacturer, reassuring the Foundling Hospital governors that they were now in a better position. I can imagine a lot of other abused workers, but not many who could use the written word to better their situations. And I am likewise thankful for the Foundling Hospital’s very thorough record-keeping so that all this is available to us today. These are fascinating objects.

Fighting Talk – Life As A Sailor

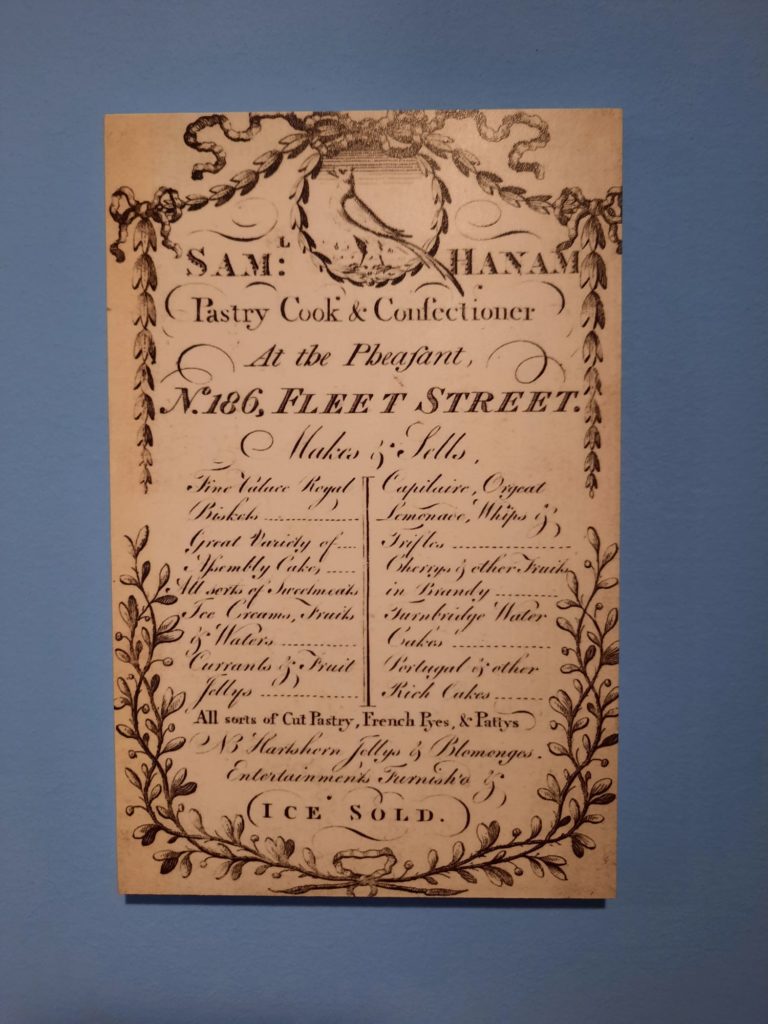

So we know a little about George King, and how it is that he came to be literate. The reason that his life was worthy of a first-hand account begins with him running away from his apprenticeship. King was an apprentice to a grocer and confectioner. He didn’t really settle into this life though, and his teething problems culminated in a fist fight with another boy. Fearing the consequences, George ran away. Which would have been worse between those consequences and being press-ganged into the Navy is maybe hard to say.

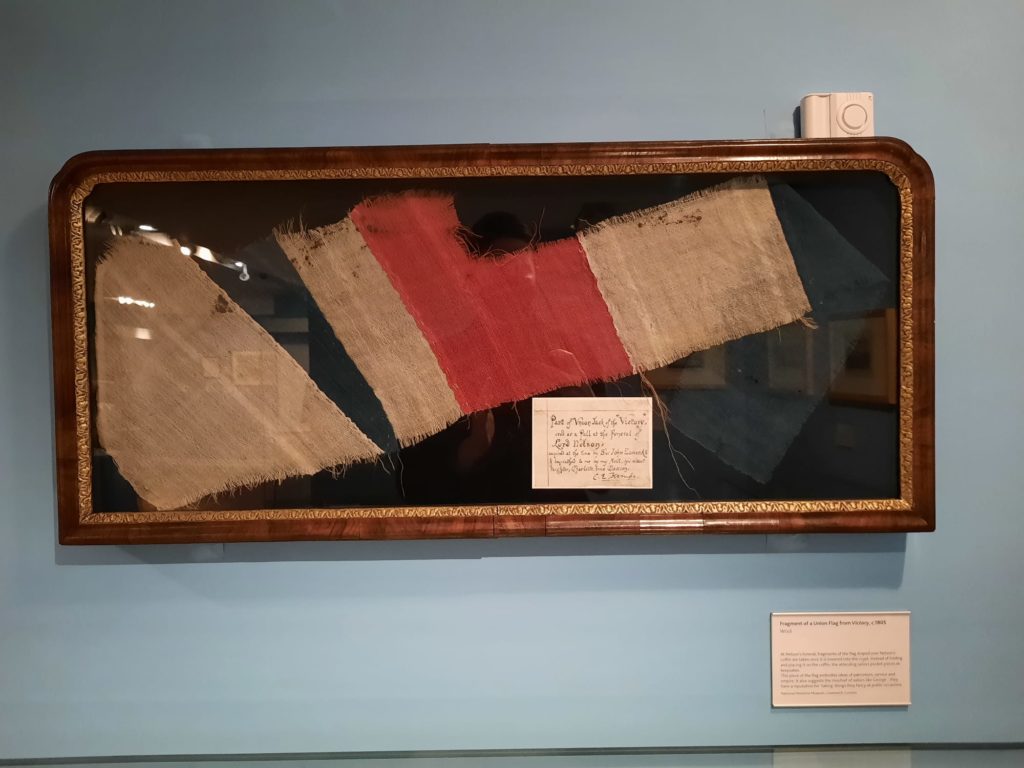

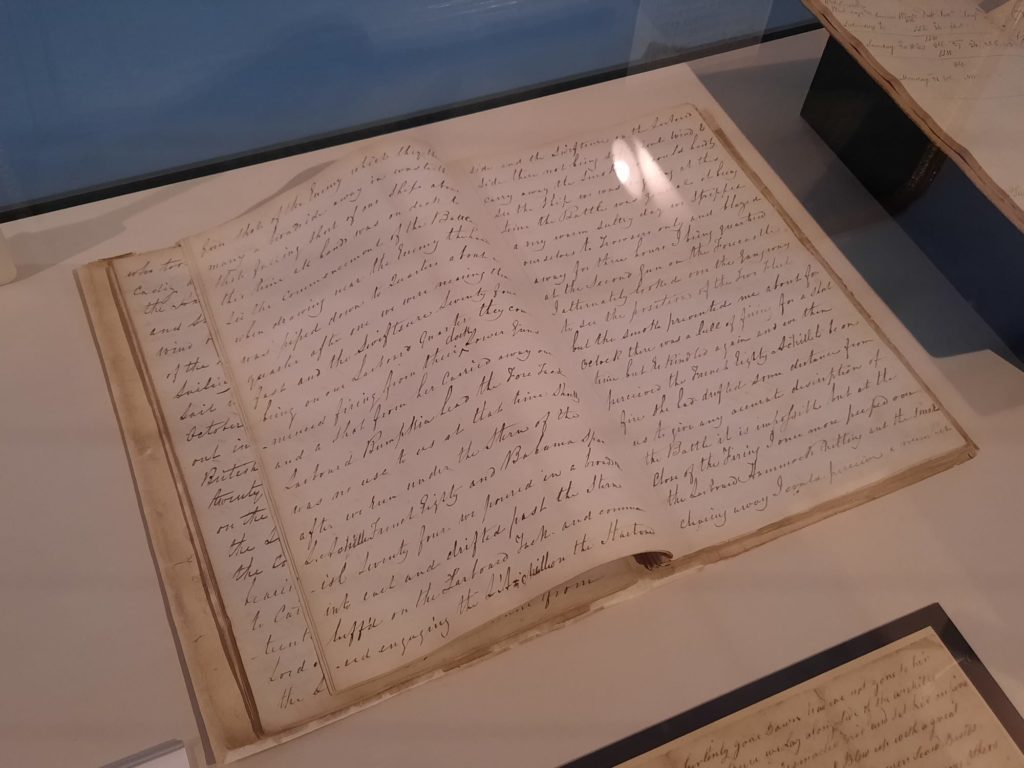

But the latter is what happened. He served on the HMS Polyphemus. This ship’s figurehead (now very fragile) is on view as part of the exhibition. What a wonderful survival! Anyway, the Polyphemus played a significant role in the Battle of Trafalgar; and it towed the HMS Victory, with Nelson’s body, back to England. Thus George King, from inauspicious beginnings, ended up taking part in a key moment in English history. No wonder he wanted to write down his memoirs.

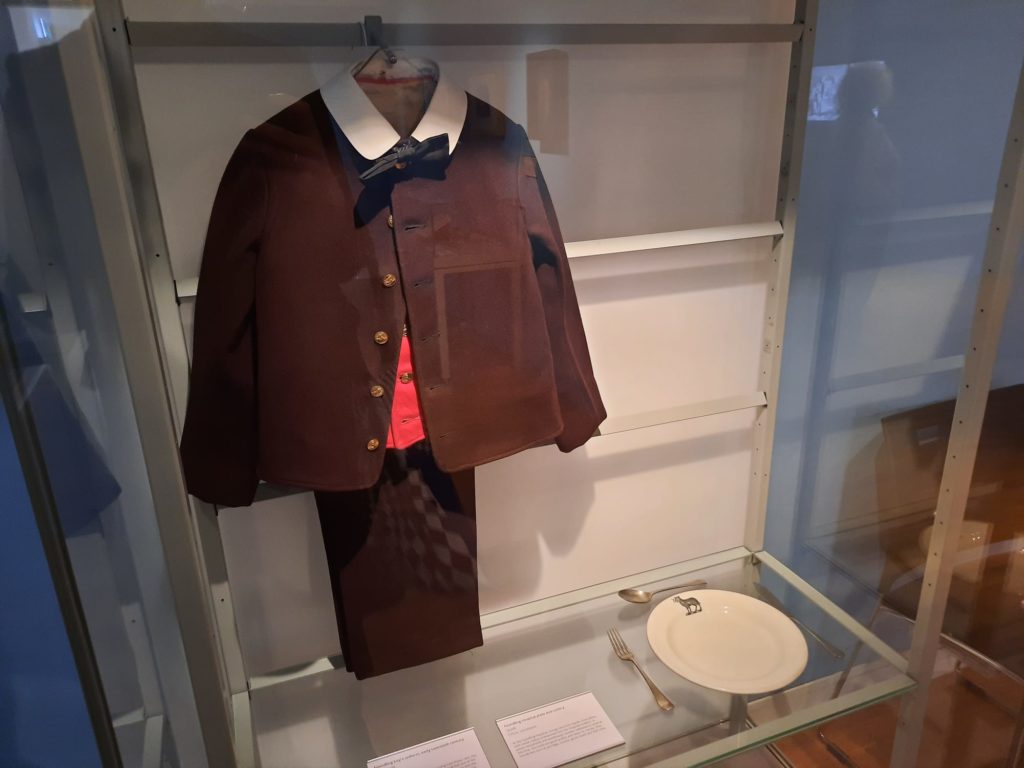

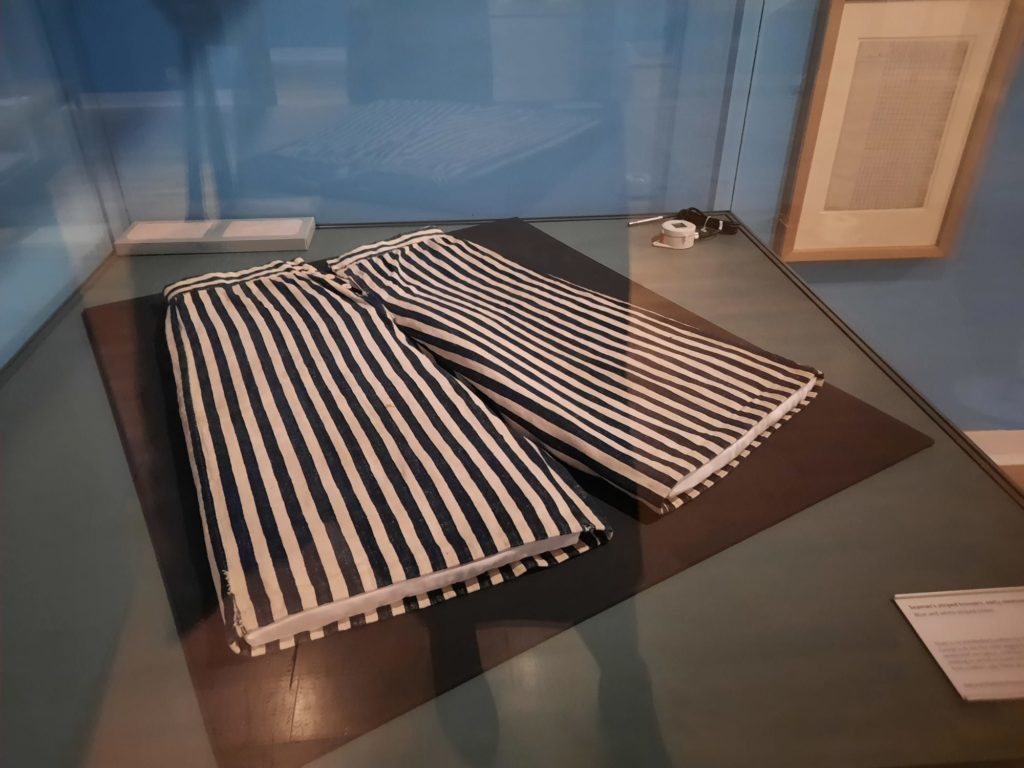

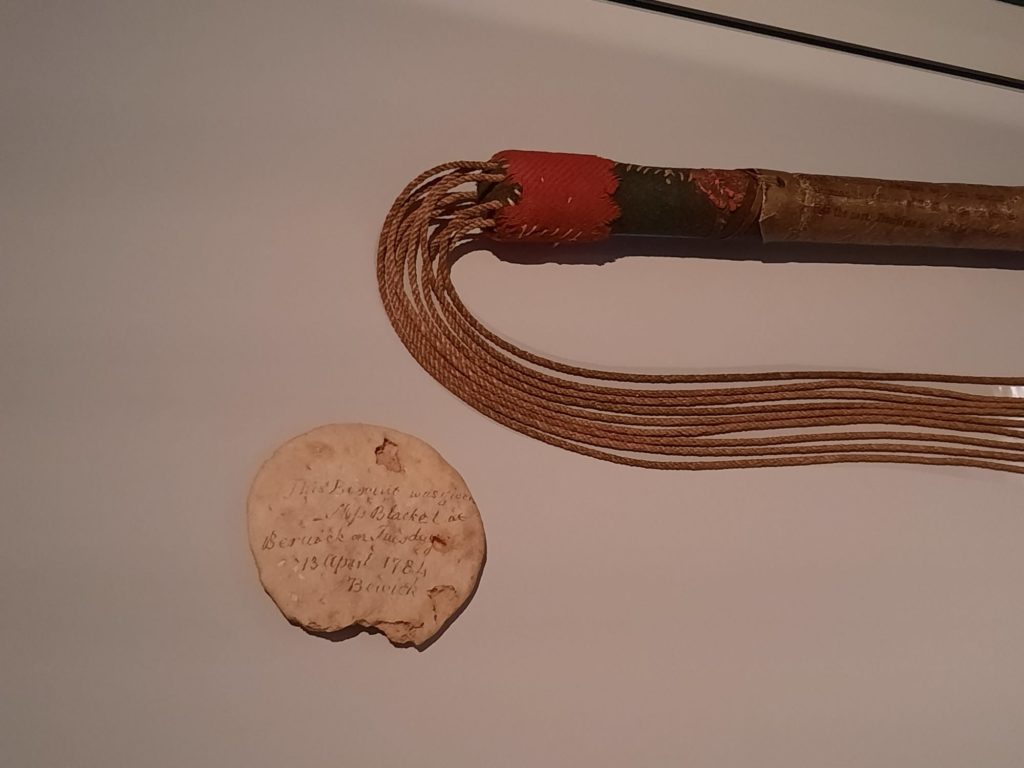

I thought the curator of the exhibition (Professor Helen Berry of the University of Exeter) did a great job with Fighting Talk. The nature of the exhibition means it’s quite heavy on archival materials. But there are also plenty of physical objects to relieve this. In the section on George’s sea-faring days, for instance, we can see sailor’s trousers, paintings, and even a ship’s biscuit from 1784 (image above). Plus a cat-o-nine-tails as we learn about his increasingly frequent struggles with and punishments for alcohol (a contemporary interpretation posits this as a symptom of unresolved trauma). This lends plenty of colour to George’s life story as we read about it, often in his own words.

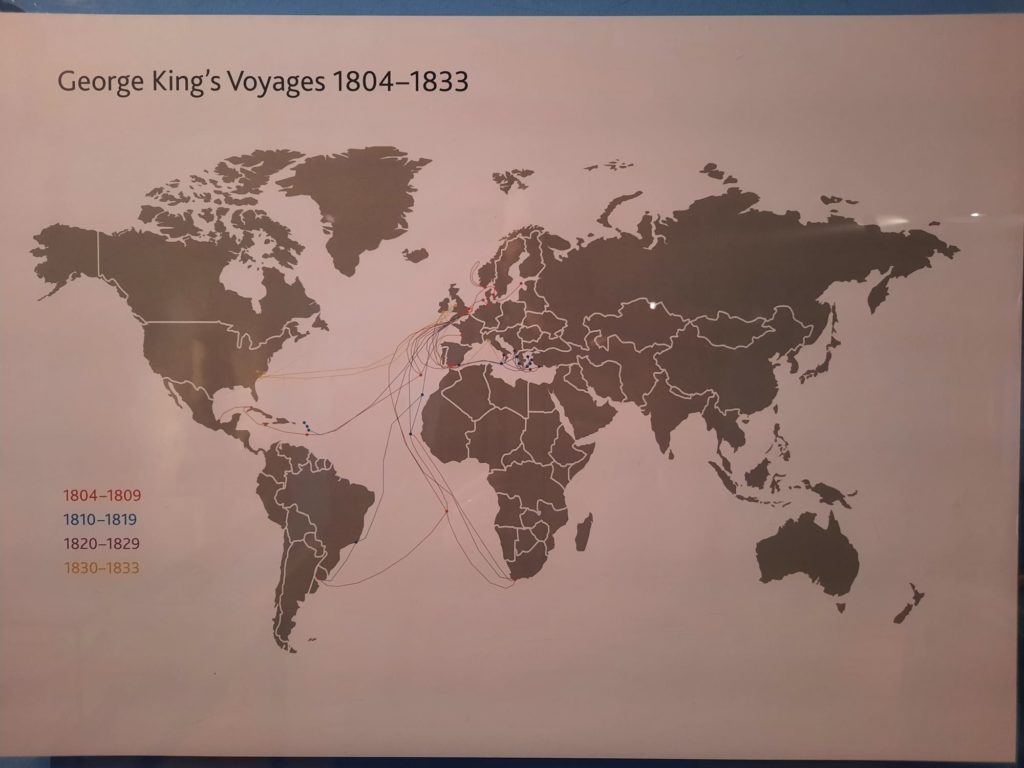

Fighting Talk – America, Then More Institutional Life In Greenwich

What is even more remarkable about George King’s life is that his adventures didn’t stop with the Battle of Trafalgar. After he left the Navy, he set off for America. A chance encounter led him to become a school master in South Carolina. This section of the exhibition is explored through a video, with interviews with Reverend Keith Magee, Professor of the Practice of Social Justice, and Christina Mobley, Lecturer in Radical Ideas and Decolonising the Curriculum, of the University of Newcastle. As an aside, the University of Newcastle sounds like an exciting place right now!

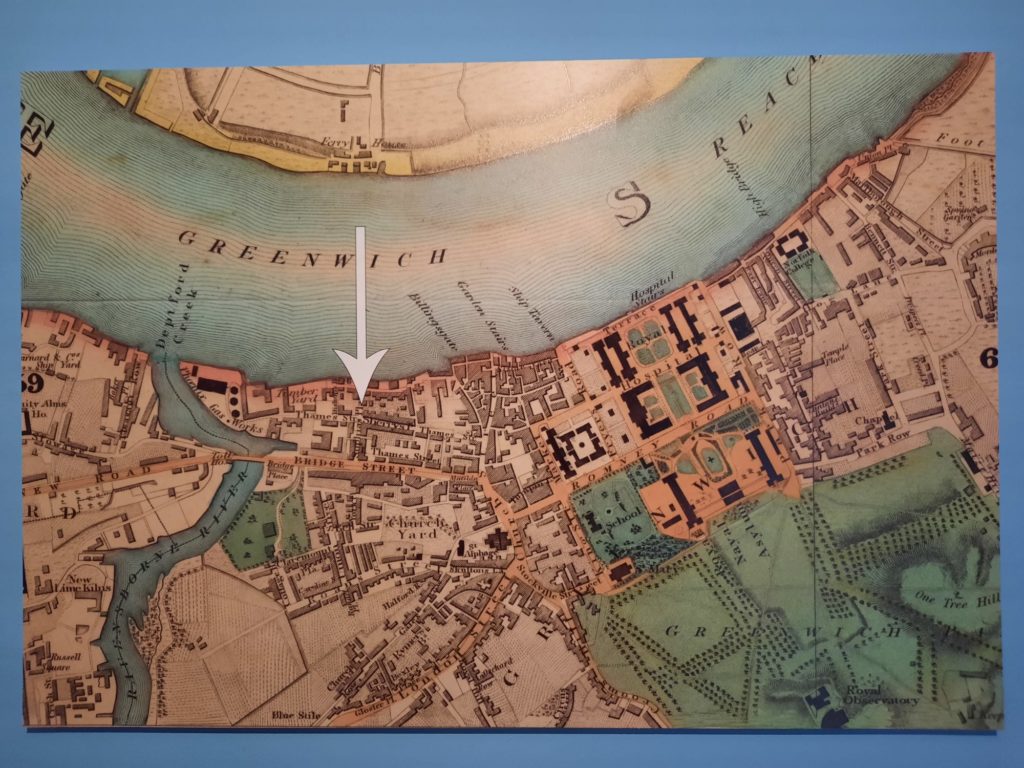

But anyway, King went off to America. The video considers his experience in suddenly finding himself a privileged White man rather than a disadvantaged Foundling; what his reasons might have been for writing very little about his encounters with enslaved people in South Carolina; and whether his early experiences in life were the reason he didn’t settle in America but instead made his way back to England. Once there, we move back into documentary evidence for his experiences. King had a naval pension by this time but it was not enough to support himself. So he re-entered institutional life, this time as a pensioner at Greenwich Hospital.

There is a happy ending, however. As he could read and write, King was able to take on extra work at the Hospital as a clerk. This enabled him to move back out, and settle down with a second wife in Greenwich (the first, in his youth, died a few years after their marriage). King lived a dignified old age, and was buried in the Royal Hospital cemetery in 1857.

I really liked the balance in the exhibition between George’s own, unique voice, and what else we can learn about his story or the story of other Foundlings, sailors and Pensioners like him. It’s a great little historic exhibition, and well worth a visit.

Another Look At The Foundling Hospital

While I was mainly there to see Fighting Talk, I couldn’t resist the opportunity to see the permanent collection again. Last time I was here was fairly early in the pandemic and things were still very uncertain. I had to enter through a side door, follow a one-way system (sort of) and so on. A few things have changed since then. Some for the better, like entering through the main entrance. But I did miss the visitor hosts I saw here last time, and hope that they are still a feature of the museum. I spoke to a very knowledgeable chap last time who imparted a lot of information about the museum’s art collection.

Otherwise it’s still a great place to visit. The story of the Foundling Hospital is incredible: how it began, the children’s lives, and its legacy today. Some of the objects, like the tokens left with babies, are very emotive. And some fun exhibits are either new or back, like the automaton (fourth image) that comes to life for 20p.

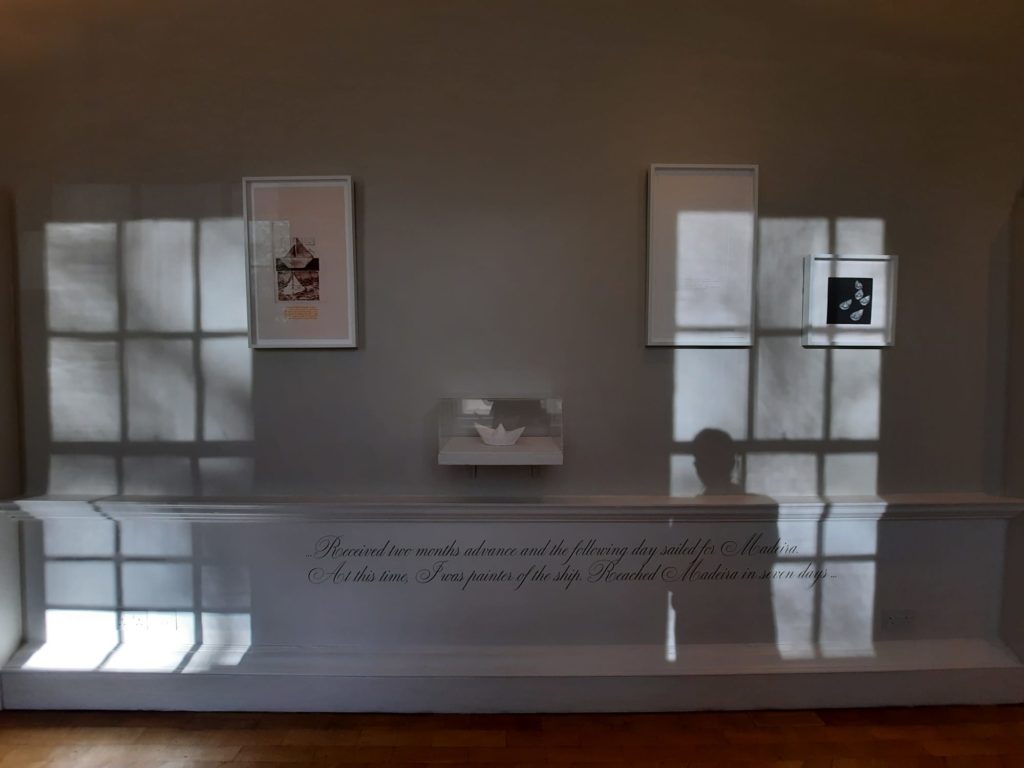

The Foundling Museum are also very good at contemporary art projects and commissions. As well as Fighting Talk, there were a couple of temporary art displays. One was very simple. Love-in-Knots is a project with the Healthy Minds Community Programme. Participants have produced artworks from a starting point of the Celtic knot design. And Ship’s Tack by Ingrid Pollard brings together fragile ceramic boat sculptures, textile works, and words from George King’s autobiography. A musical playlist to accompany her work can also be found here.

So if you visit for Fighting Talk, do take in the museum as a whole. It’s a great spot, and fast becoming one of my favourite small London museums.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Fighting Talk on until 27 February 2022

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.