Kehinde Wiley At The National Gallery: The Prelude – National Gallery, London

A small exhibition of works by Kehinde Wiley at the National Gallery encourages contemplation of the meaning behind his recentering of Black men and women in Western art history. Food for thought.

Kehinde Wiley At The National Gallery

I wrote recently about how exhibitions at the National Gallery are often very academic, and best treated as a pleasing break from the outside world. Well, to counterbalance this tendency, the National Gallery also has a programme of exhibitions by living artists. Kehinde Wiley: The Prelude is the latest in this series, and like those which have gone before, this exhibition creates a fascinating dialogue with the gallery’s collection.

In this case, and building on Wiley’s earlier work, the exhibition recentres Black individuals in the Western (White) art historical canon. Through our reactions to something unexpected, we confront the truths behind what we may have considered to be universals. The linear narrative of artistic schools and artists. Who is present/missing and how they are represented in art. The wider ramifications of a world centred on one type of people, with everyone else as ‘other’.

For some of us, these are big, possibly daunting questions. For others, they are daily, lived experience. But for any viewer, Wiley’s work provides an entry point for thought and discussion. This latest exhibition at the National Gallery may be small, but it is perfectly formed for this purpose.

Kehinde Wiley at the National Gallery – The Paintings

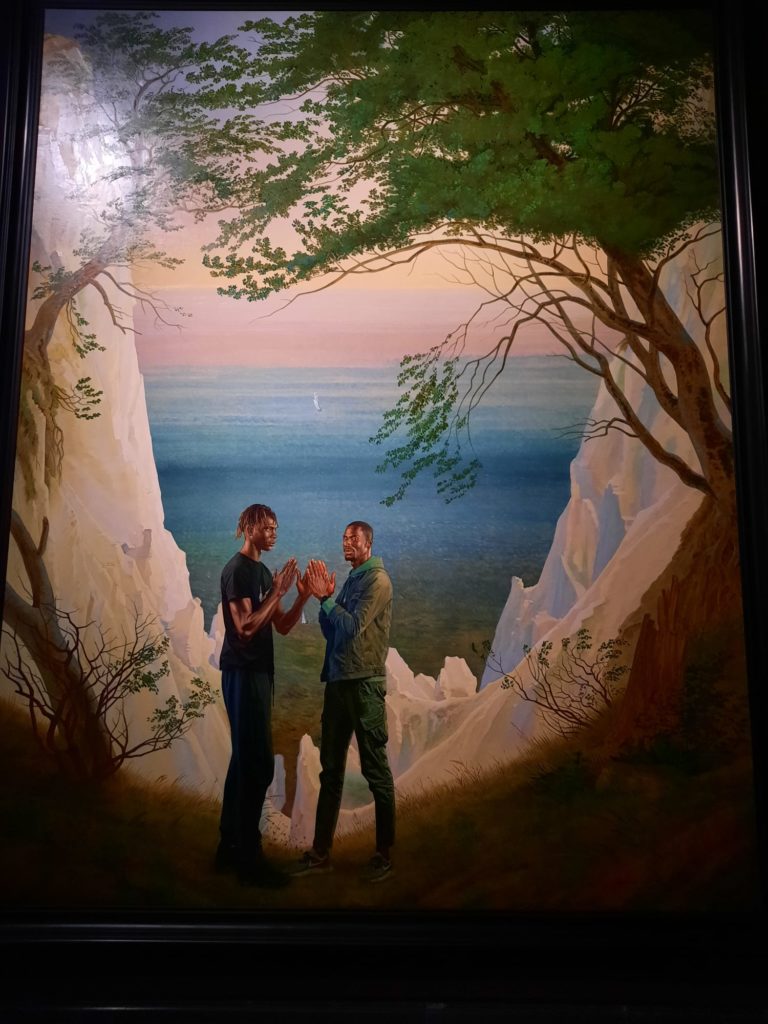

Kehinde Wiley: The Prelude is an exhibition in two parts. In rooms right at the heart of the National Gallery, the viewer first comes across a small selection of paintings, followed by a video installation on six screens. For anyone who has seen Wiley’s work (and we had a very small taster at Ely Cathedral in the summer), the format and subject matter will be familiar. Wiley often scouts Black models for his paintings on the streets of London, New York, Dakar, etc. He transposes these contemporary people into historic paintings, retaining the title and enough of the original to make it recognisable while not aiming for a precise copy.

The paintings here follow this format. We see images we recognise, like Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. Heironymous Bosch’s Ship of Fools. But they are different, modern, scaled-up. The colours are heightened, the light and shade dramatic. There is no mistaking the realness of their subjects. They are people we might meet on the streets outside. But in the other galleries of this institution they are barely represented. When you leave the exhibition and walk through the permanent collection to exit, this contrast is starker than ever.

There is something very complicated about recentering Black figures in Western/white art history; it will take me a long time to think it through. Meanwhile, there is no doubt that Wiley’s paintings are impressive in their scale and technique. I only wish there had been more of them – five hardly seems enough.

Prelude

Moving past the paintings, we come to the film which gives the exhibition its name. The premise of Prelude is similar to the paintings I described above. After an open call in London, Wiley took his chosen individuals to Norway. Here, he filmed them against dramatic winter landscapes, the enveloping whiteness a metaphor. We see Black men and women walking through the snow, playing pat-a-cake games, holding smiles until their muscles freeze and they grimace. The film runs at just over 30 minutes, but is beautiful and worth watching from start to finish.

What I found myself pondering as I watched Prelude is a little of what I spoke about here. The Romantic notion of certain landscapes as ‘sublime’, a place to contemplate man versus nature and therefore man’s position in the world, endures today. And it has shaped how we (but who is we?) think about the natural world. Yet the Romantic man is not a universal man, he is a White man. And the sublime landscape is a Western construction, not a universal truth. It is easier to see this or remember it when Wiley confronts us with images, with people, we do not expect to see against a backdrop of Scandinavian blizzards and the words of Wordsworth or Henry David Thoreau.

So overall I found this to be a very aesthetically pleasing exhibition, which asks us to be honest about art history and race in order to properly make sense of it. I found this an exciting challenge (which I recognise is a demonstration of privilege on my part), and thoroughly enjoyed the exhibition in spite of its small size. Prelude is free to visit, so essential viewing for anyone stopping into the National Gallery.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Kehinde Wiley at the National Gallery: The Prelude on until 18 April 2022

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

3 thoughts on “Kehinde Wiley At The National Gallery: The Prelude – National Gallery, London”