Bow Street Police Museum, London

A visit to the Bow Street Police Museum reveals a proud history of pioneering police work in this part of London.

A History of Early Policing At Bow Street

I have been to the Royal Opera House numerous times. And yet I don’t think I had ever paid attention to the building just across the street. Now a luxury hotel, it was previously shared between the Bow Street Magistrate’s Court and Police Station. The history of policing on and around Bow Street goes back much further than this building, however. In fact, Bow Street (as those who have heard of Bow Street Runners will know) goes right back to the birth of modern police forces and methods. So I am immensely glad that the NoMad group have turned over a corner of the building to serve as the Bow Street Police Museum. And also glad that I did some detecting of my own; I spotted the museum one evening as I waited for a friend before an evening of ballet.

But back to Bow Street and policing. We take it for granted that something like a police force should exist, but it hasn’t always. Before the advent of the modern police force, local people would often come together to organise watchmen. Minimally armed, their primary job was to deter crime rather than fight off or “arrest” criminals. So they often carried bells or rattles. But the thing was, as cities grew exponentially after the Industrial Revolution, watchmen just weren’t cutting it any more.

The next phase in policing was still fairly organic and not a public function. But things began to be more organised. In 1740 a magistrate, Thomas de Veil, opened a court in his family home in Bow Street to investigate local crime. He wasn’t formally trained in law but was quite effective, even doing his own detective work. Henry Fielding took over the house and court when de Veil died in 1746. The need for a large supporting organisation of constables was growing. Fielding thus obtained a government grant to set up a more structured and disciplined system. When Fielding in turn died, his half-brother John took over, and further expanded operations.

Developing a Modern Police Force

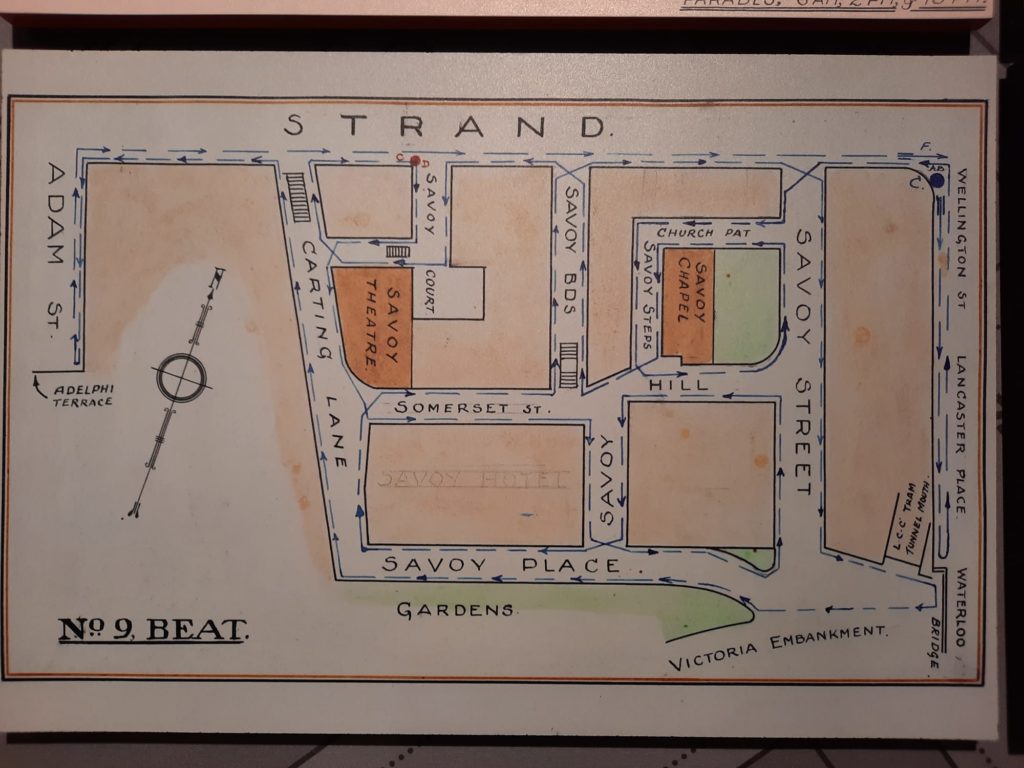

Things continued in this way for a while, with each new magistrate having the power to shape the people under him who detected and detained criminals. Calling these men ‘Bow Street Runners’ seems to have started about the time of John Fielding. Keeping up with the expansion of London’s population and its crime-fighting needs was a challenge, however. Thus, in the 1820s, Home Secretary Sir Robert Peel began to advocate for a single, centralised police force. This was approved by parliament in 1829. ‘Peelers’ and Bow Street Runners worked in parallel until 1839 when the latter were merged into the Metropolitan Police Force.

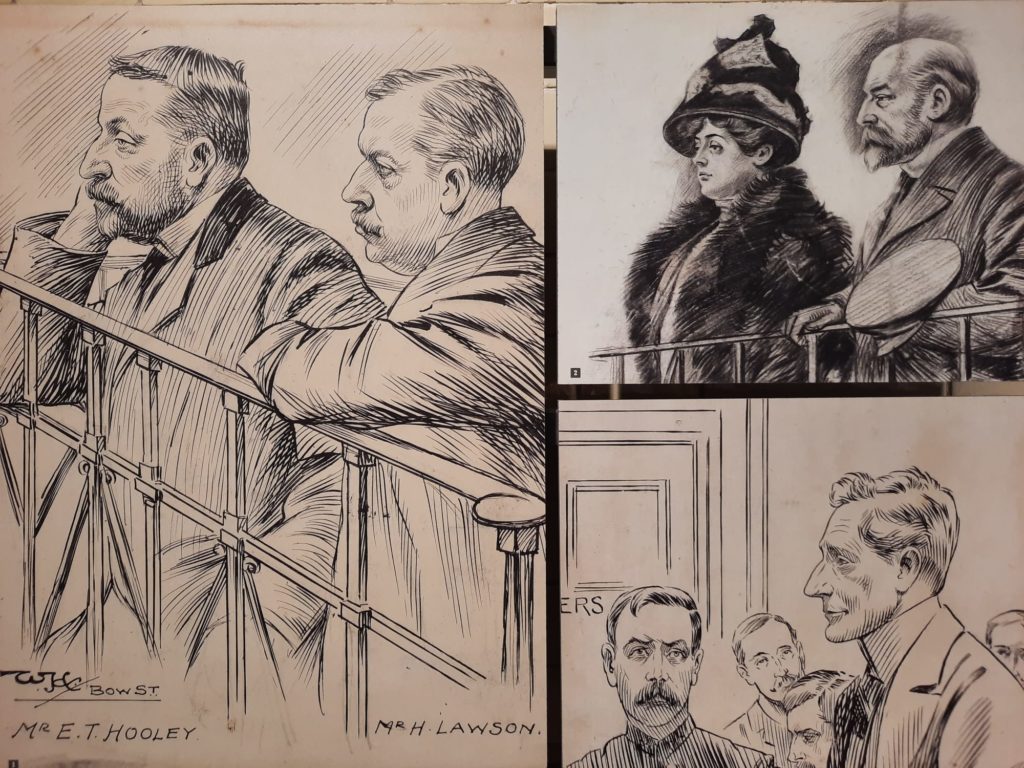

As part of the Met, Bow Street continued to have an important place in policing. The Bow Street Magistrate’s Court heard high profile cases including Oscar Wilde, the Krays, Dr. Crippen, Suffragettes and General Pinochet. The many police officers who worked at Bow Street over the years felt connected to their station’s illustrious history, and proud to uphold it. By the 1980s, however, it was clear that the building was no longer fit for purpose. It closed as a police station in 1992, with staff transferred elsewhere. The court continued to operate for several more years.

Even today, however, the Bow Street name looms large in the history of policing. Having a new museum (opened in 2021) to tell this story feels special. That you are still able to experience what the building was like as a police station makes it even better.

Visiting The Bow Street Police Museum

Given the size of the building as a whole and of the former police station within it, the Bow Street Police Museum is fairly compact. There is a decent-sized room which has historic information about the evolution of policing at Bow Street. And then the main attraction, which is a row of holding cells. Nonetheless, I must have spent about an hour here as the content was so interesting.

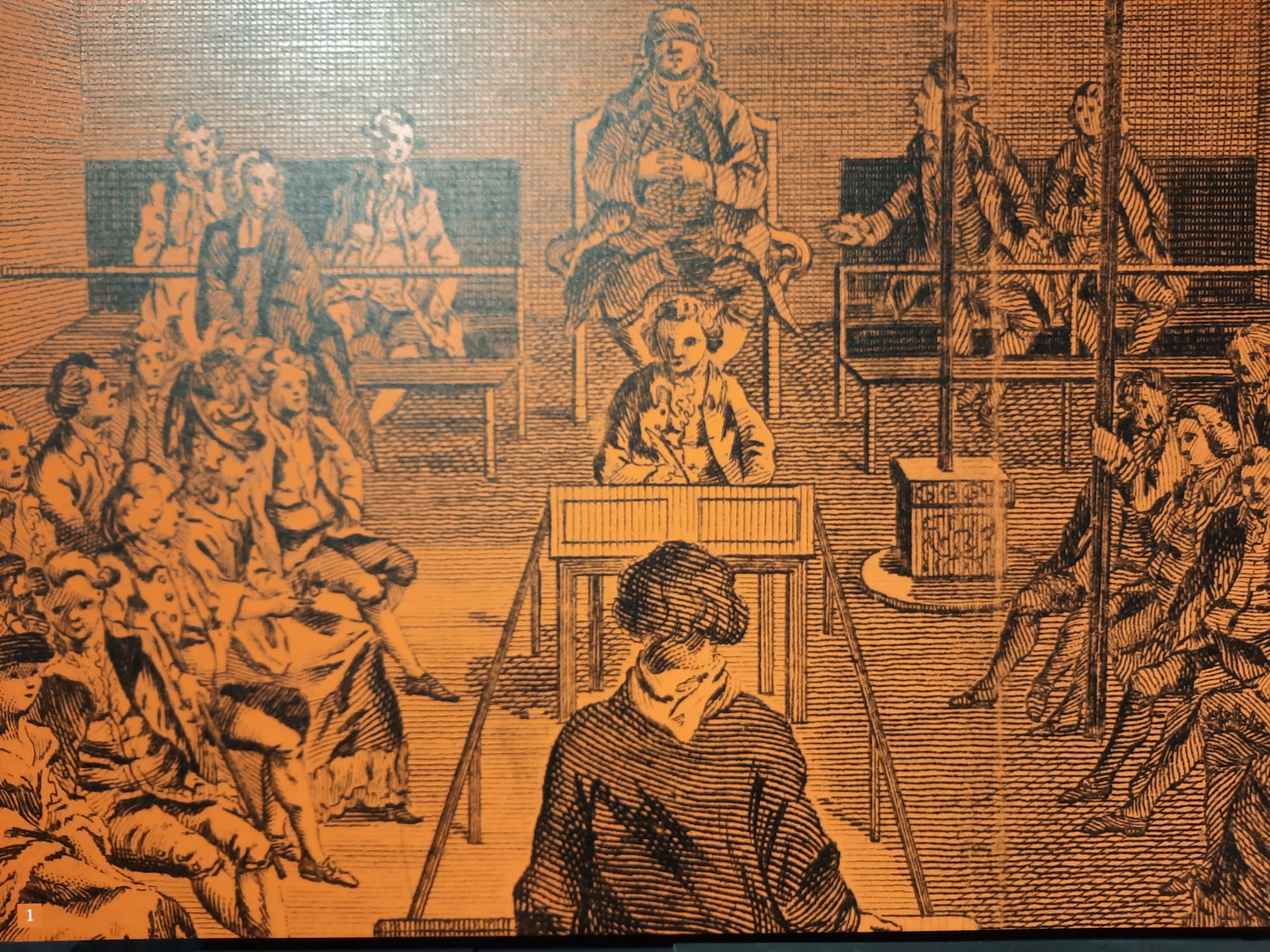

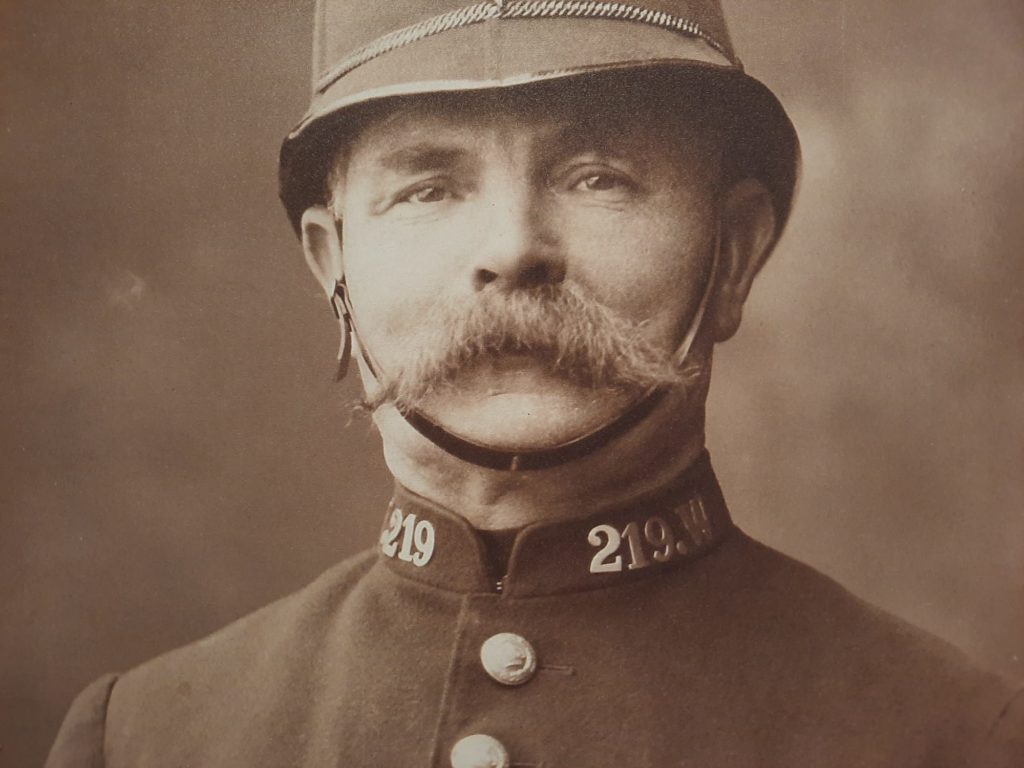

The historic overview is a mixture of text and objects. The highlight here is an original dock, which you can step onto (set up as a photo opportunity). When you come to read about some of the high profile cases later on, it’s good to have this frame of reference for just how narrow the docks were. Among the objects on display are a rattle, uniform and cutlass to give a sense of those early days. But really it’s about imparting information through text and archival images. Everything is very clear and easy to read. And also gives a sense of the impact of this particular location and community on how policing at Bow Street developed.

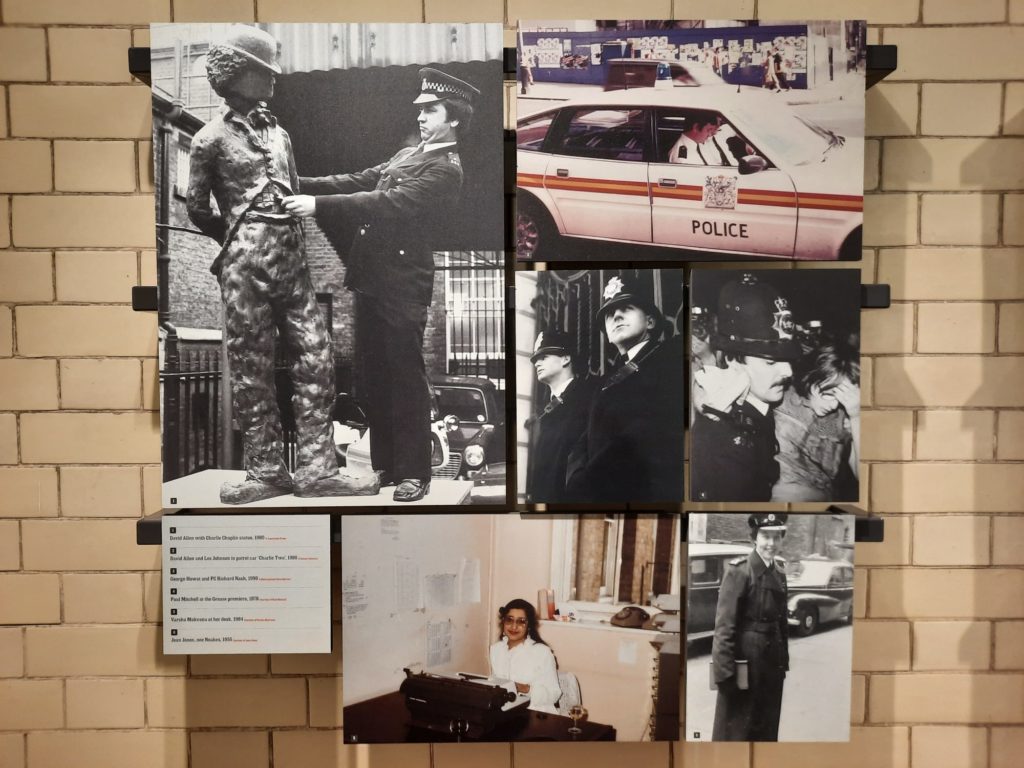

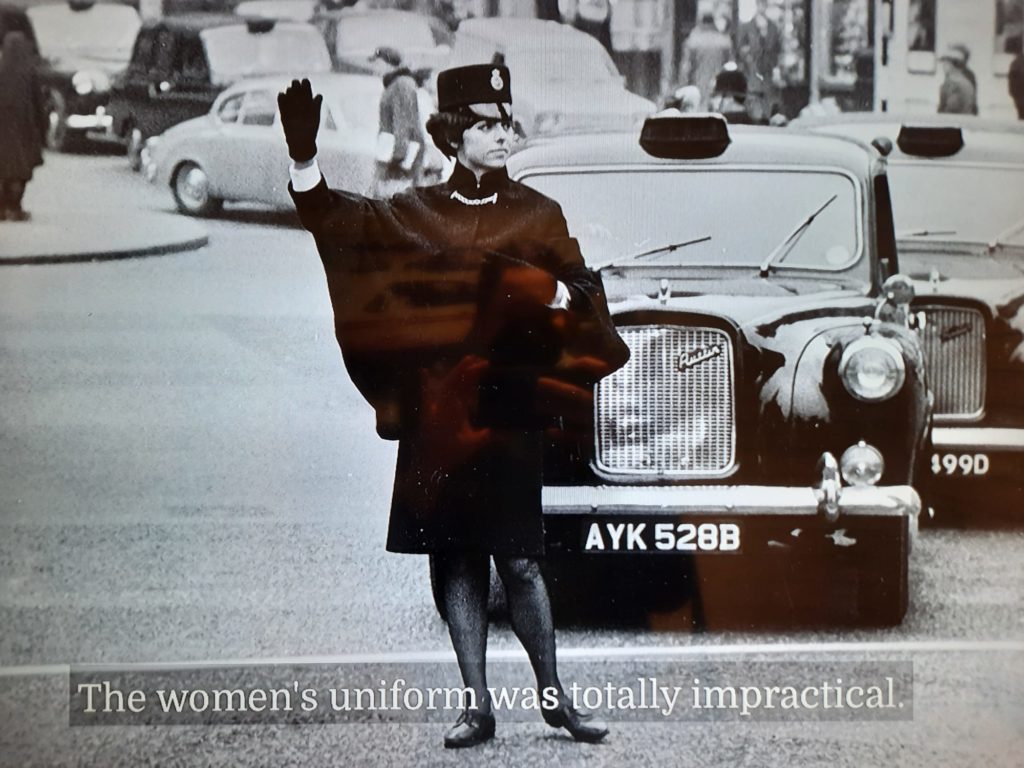

As a Part II to the museum experience, the cells are really interesting. One is set up to show you what they were like when detained men (the women’s cells were upstairs) were held here overnight. And the rest have thematic content, for instance on what it was like to work there; how the roles in a police station are structured; different types of pioneering police work, such as welcoming the Met’s first black officer, Norwell Roberts, or working with the local Chinatown community. And so on and so forth. There are more images, text and objects here. But the most interesting part is the work the museum has done to capture oral histories. A range of former Met staff who worked at Bow Street give first hand accounts of their time there. It really brings it to life.

Final Thoughts

Whether you are visiting London, have a special interest in policing history, or have an hour or so to spare around Covent Garden, I highly recommend a visit to the Bow Street Police Museum. I found the history and personal stories really interesting, and it added to my mental map of London and its past. Acknowledging that not everything can stay as it is indefinitely, it’s also a nice way to salvage part of a historic building when that building no longer suits its original purpose.

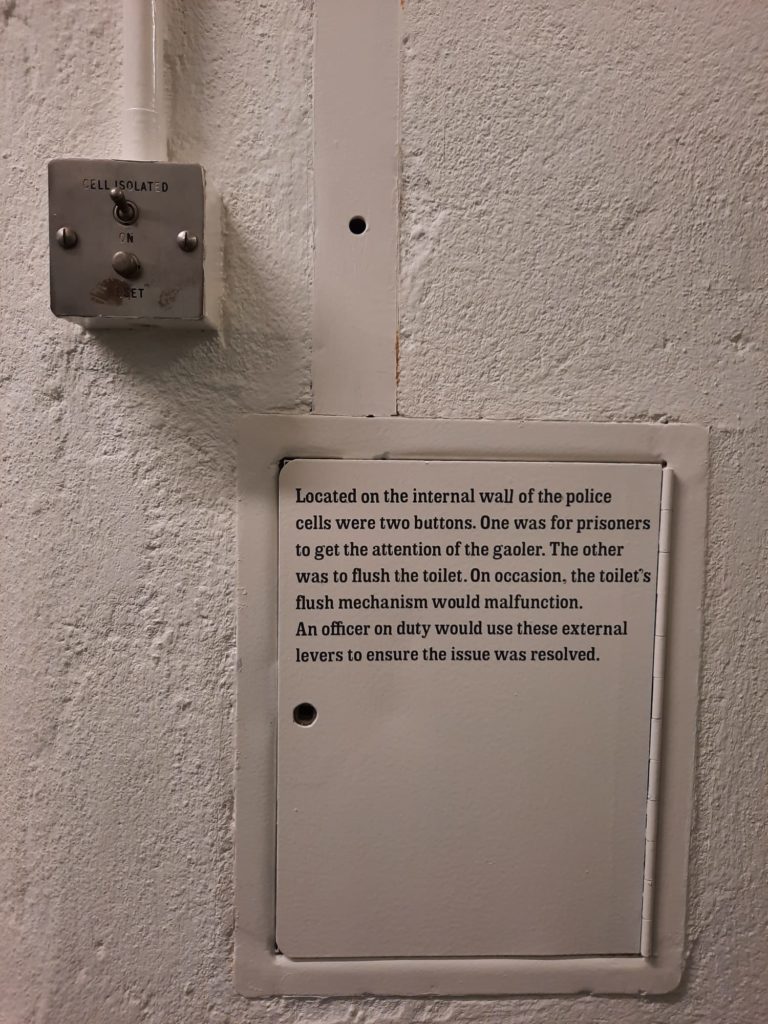

Two more things that I will add here to entice you to visit. Firstly, the staff are very welcoming. When I visited they gave a quick but thorough orientation, and as it was quiet we were able to chat for a bit as I was heading out. And finally, I realised after I had seen the cells that this is what the visitor bathroom was in a former life. I wondered what the sign about a flush at the far end was about. When else can you say you’ve been in a real life cell in one of the most famous police stations in the world?

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.