Hogarth And Europe – Tate Britain, London

A review of Hogarth and Europe, on at Tate Britain. This sprawling exhibition certainly has a great number of Hogarths on display. If only it was a little more focused.

Hogarth and Europe

I had seen some reaction to this exhibition before I saw the exhibition itself. So I knew the Tate had done something ‘woke’ with its Hogarth exhibition which had upset some more traditional critics and visitors. This didn’t put me off (clearly) – I enjoy exhibitions which challenge accepted points of view and introduce new perspectives (like this).

So off I went to the Tate for Hogarth and Europe. The premise according to the Tate’s website is not dissimilar to Turner’s Modern World, which was also at the Tate. That is, looking at an artist in terms of their reaction to a rapidly changing world. Only this time Hogarth’s European contemporaries are also included. And as an additional layer on top, a group of 16 commentators from different fields and backgrounds have been invited to reevaluate many of the works on display. You may be thinking this is quite a lot. You would be right.

In the end my issue wasn’t with the ‘wokeness’ of this exhibition by any means. There were some interesting perspectives in there. But, to quote a former boss of mine, I was left wondering ‘What’s the “so what?” from all this?’ What was really the point that the curators were trying to make? Hogarth and Europe was in the end a little big and a little information-heavy and a little tiring for me to figure this out.

William Hogarth

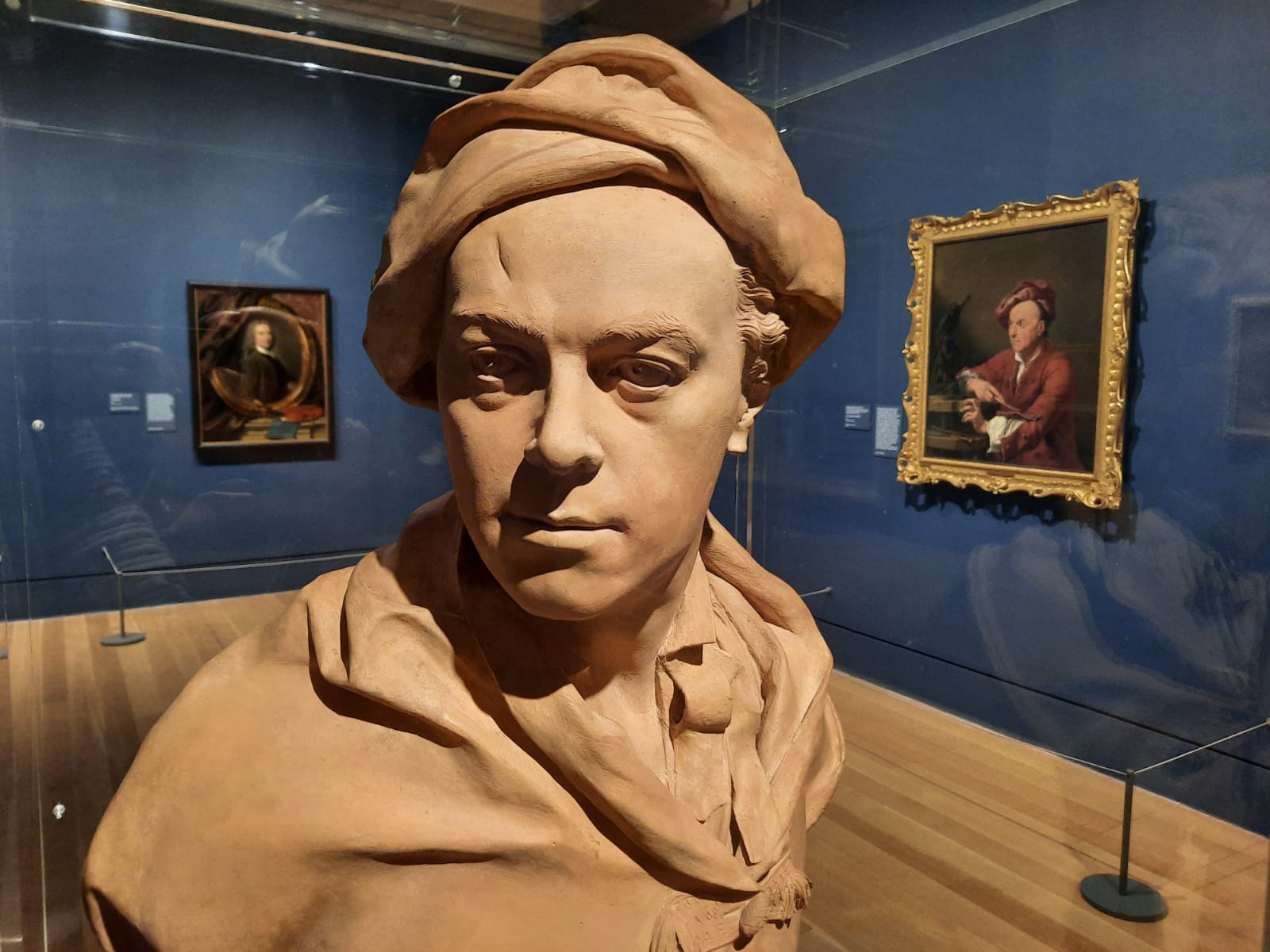

Hogarth is an interesting artist, and a good choice to illuminate aspects of 18th Century life and artistic practice. Born in 1697 to a lower middle class family, he started an apprenticeship with an engraver but did not finish it (although used these skills to control the distribution of his images later in life). He was a successful and popular artist, despite a hard edge of social commentary and moralising in his work. He was working at a time when printing technologies allowed greater distribution (and therefore wider fame) for artists, and made the most of these channels. And Hogarth supported causes which aligned with his moral viewpoints, and we have therefore seen some of his works before in the collection of the Foundling Museum.

Some of Hogarth’s most enduringly popular works are his series charting the downfall of various individuals. There is A Rake’s Progress in which a grasping young man ends up in Bedlam asylum. A Harlot’s Progress – you can probably figure that one out. Marriage A-La-Mode, illustrating the tragedy of marrying for money. And there are one-off works in a similar vein, such as the pairing Gin Lane (bad) and Beer Street (healthy).

One of the key points that Hogarth and Europe posits is that it wasn’t just England which was changing rapidly in the 18th Century, and it wasn’t just Hogarth who reacted to it. So throughout the exhibition, we see works by some of his British and continental contemporaries, including Watteau, Chardin, Longhi, Canaletto, Cornelis Troost and others. If this was the purpose and focus of the exhibition that would have been one thing. But wait, there’s more!

The Many Strands of Hogarth and Europe

So. As well as getting to know the work of William Hogarth, understanding it in the context of the society he lived in and seeing the work of some of his contemporaries, there are many other things going on in Hogarth and Europe. If you try to take it all in, you will learn about map-making; social change in London, Paris, Venice and Amsterdam; detailed analysis of Hogarth’s working practices (through x-ray, infrared and paint analysis); an 18th Century trend to show you were a ‘good sort’ by having an unflattering portrait painted; Hogarth’s direct and indirect connections to racist and sexist imagery; the business of creating and distributing engravings; the 18th Century ‘conversation piece’; early portraiture of Black Europeans. And more! At one point I was genuinely dismayed when I approached what I thought was the end of the exhibition and realised there were three more rooms to go.

And I think fundamentally this was the issue for me. It’s too big. It’s like they had a particular space to fill and kept adding more in until it was full. Hogarth and Europe could have done with being a lot more focused. As in: here’s Hogarth, the purpose of this exhibition is to resurface some difficult questions, and here are a limited number of comparative works to support this. Or, this is what it was like to be an artist in 18th Century Europe, and we are viewing that through the lens of Hogarth.

As it stands, it feels like you’re seeing several exhibitions together. I did something which proved to be very successful for the last couple of exhibitions I saw at the Tate and bought a ticket for the last slot of the day. I was a little bit glad when they started clearing the galleries for closing and I had to hurry up and leave.

Reinterpreting Hogarth

So what about all those commentators, then? Well as I said earlier, I really quite like challenging viewpoints. There are 16 commentators on this exhibition, so a lot of varied and interesting thoughts. There are academics specialising in Dutch art, representations of madness, art and violence, and reversing the Western gaze. Also contemporary artists and conservators. And many more besides. I was experiencing total information overload in this exhibition, so sadly I didn’t take in as much as I would have liked to. Particularly as many works have commentary by more than one person – again interesting, but a lot to read and understand.

There are good and bad ways to shine a contemporary light on historic art. The Tate don’t seem to have it quite right here. Personally I found the Wallace Collection’s audioguide for their Frans Hals exhibition a much more effective way to introduce different points of view. Whether the lack of editing with Hogarth and Europe is a result of institutional confusion as the Tate balances its historic and modern arms, or just an enthusiasm to share the greatest amount of knowledge possible, I’m not sure. But I still don’t quite know who the intended audience was, other than that I don’t think it was me.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 2.5/5

Hogarth and Europe on until 20 March 2022

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

One thought on “Hogarth And Europe – Tate Britain, London”