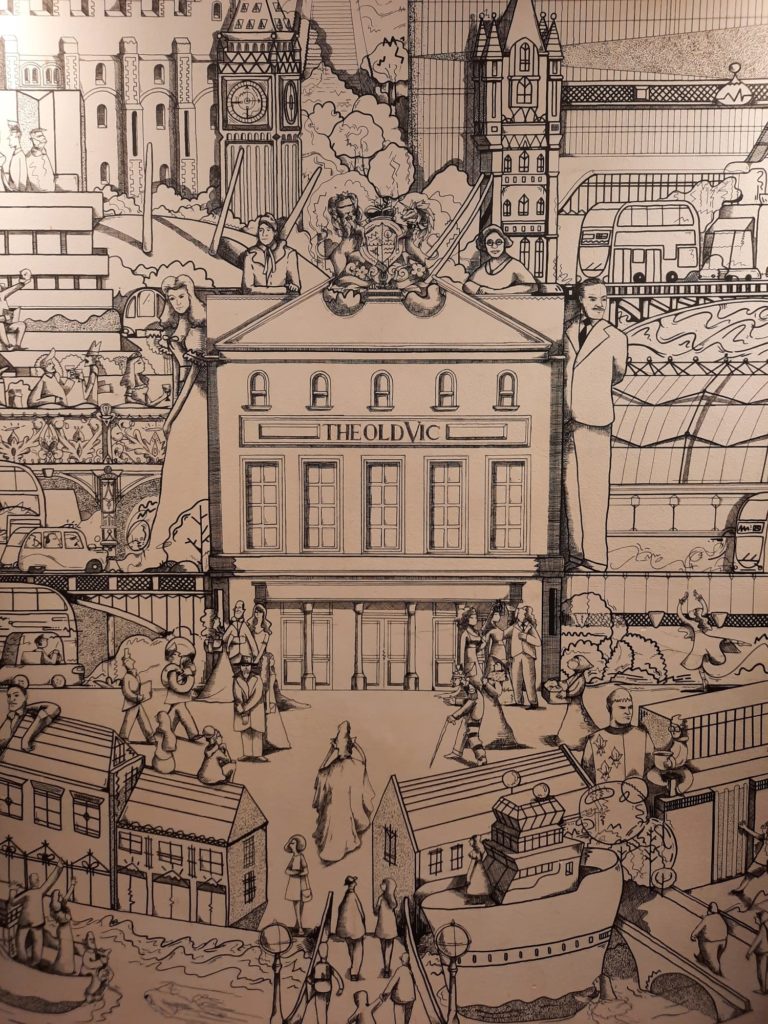

A Number – The Old Vic, London

A review of A Number, a Caryl Churchill revival at the Old Vic. Lennie James and Paapa Essiedu get to grips with father and son relationships, inheritance and identity in this tense, hour-long drama.

A Number

For me, seeing A Number at the Old Vic was a bit of a bookend moment. In March 2020, a friend and I saw the same play in a different production at the Bridge Theatre. Things were decidedly abnormal already – I was working from home, had done a bit of light stockpiling… But the performance went ahead so we attended, sitting outside afterwards and discussing the Covid situation and how strange everything was. We finished the conversation talking about booking for The Book of Dust, which was to open in Summer 2020, assuming things would be back to normal by then. We eventually saw it at the end of 2021!

So to have the same play back on again in March 2022, just as (for better or worse) all restrictions are being lifted in the UK, seemed appropriate. It’s also an intriguing play, so I wanted to see what director Lyndsey Turner would do with it.

A Number was first performed in 2002. Caryl Churchill wrote it a few years after the fierce debate about cloning (remember Dolly the sheep?). It deals with a father, Salter (Lennie James), and his son/s (Paapa Essiedu). Because, as it turns out, the son we first meet is a clone. Or is he the original? Salter is not forthcoming with the full details of what happened, and we leave the play with some uncertainty as to how the ‘unauthorised’ clones of his sons might have come about.

But clones there certainly are. Throughout the approximately hour-long play we meet some of them, as well as Salter’s naturally-conceived son Bernard. Churchill explores themes directly related to cloning: what would be the ‘right’ reasons to clone a human being? She also explores deeper themes of identity and inheritance, nature and nurture, and ultimately some pretty hefty questions about morality.

Humour Amongst The Darkness

A Number is a play which offers a real opportunity for actors to flex their muscles. The role of Salter is challenging. How do you play a man who has done some terrible things, without losing the sympathy of the audience? For the actor playing Salter’s sons the challenge is even more immediate. The audience needs to be able to distinguish immediately between each version/clone, and to connect with their stories.

James and Essiedu make the most of these opportunities. Lyndsey Turner extracts the humour from the text to a greater extent than the previous version I saw. James is masterful as Salter, pleading his case, alluding to payouts, shifting his story as it suits him. I remember being really astounded at the Bridge by how different each of Colin Morgan’s characters was and I felt this to a slightly lesser extent with Essiedu, but those distinctions are still there. One bemused and deflecting with humour. One cold, his resentment rising. And one… well, go and see it for yourself.

One thing I really loved about the current production was the set, by Es Devlin. An ordinary flat is boxed in, blood red. It’s a bit like a laboratory somehow, as well as alluding to the tension and violence of the story. I was less sold on the lighting design by Tim Lutkin. Intense flashes mark the scene changes and allow for some sleight of hand costume changes as well. But from where I was sitting it was not just disorienting, it was painful.

This is nonetheless a great opportunity to see two excellent actors in a play that is still relevant and thought-provoking twenty years on from its debut. As one of a pair of Covid bookend theatre outings, I could have done far worse.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

A Number on until 19 March 2022

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.