Gainsborough’s Blue Boy // Ali Cherri: If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed? – National Gallery, London

Another double bill of small National Gallery exhibitions, this time featuring Gainsborough’s serene Blue Boy against Ali Cherri’s exploration of artworks which have been defaced while on display here.

Another National Gallery Double Bill

I really enjoy doing posts about small exhibitions at the National Gallery. Firstly, they do a lot of one-room exhibitions, which I love. In and out, no museum fatigue! And because they do a lot of them, there is a lot of variety, often at the same time. I’ve seen a themed exhibition on sin, work by Bellotto and Kehinde Wiley, and did a previous double bill of a multi-sensory experience of a Gossaert painting and little-known (in the UK) Polish artist Jan Matejko.

Today I’m back with another compare-and-contrast double bill of small, free exhibitions. First up is Gainsborough’s Blue Boy. Sold to an American collector around a century ago, this painting caused a sensation when it went on display at the National Gallery before its transatlantic departure. Now it’s back for a limited time only. The second exhibition is very different. Artist in residence Ali Cherri has selected a handful of works which were damaged or defaced while on display in the National Gallery. Through symbolic displays, he focuses not on the whys and wherefores of the perpetrators, but on the damage to the artworks themselves. It’s intriguing and powerful.

The purpose of a compare and contrast must be to draw some sort of parallel or lesson from looking at both exhibitions at once. I think in this case it’s about privilege. Gainsborough painted wealthy sitters, foregrounding their taste and power. That the ‘Blue Boy’ was so beloved at the time of its departure tells us something about British society at that time, and what it valued. Ali Cherri’s selection of artworks tell us how fragile such privilege can be. Even treasured paintings on the hallowed walls of the National Gallery can be shot, slashed and overpainted. With care they can overcome this violence. But surely a trace remains. So for me it’s indicative of a confident nation a century ago, and a more uncertain time now. Perhaps I’m reading too much into it? You will have to read on and make your own mind up!

Gainsborough’s Blue Boy

Thomas Gainsborough’s painting of a boy in a silvery-blue Van Dyke-style outfit made a record price in 1921. The Duke of Westminster sold it to American art collector Joseph Duveen. Before it travelled to its new home, the painting stopped off at the National Gallery for a last public viewing on English shores. It caused a sensation – 90,000 visitors over three weeks. Now, exactly 100 years later, it is back.

The Blue Boy is a good demonstration of Gainsborough’s style. It has a flair for the dramatic, with the self-assured youth posed against a lowering sky. It looks back to art historical tradition, particularly Anthony Van Dyck, who Gainsborough deliberately emulated. Yet it demonstrates virtuosic brushwork in comparison to Van Dyck’s controlled style. To complete the comparison, two additional works by Gainsborough and two by Van Dyck are on display to complete the mini exhibition.

There was quite a lot of press coverage about the return of the Blue Boy to the UK. And yet… I can’t help but think that artistic tastes are not what they were a century ago. This is probably not what your average person would now pick as the epitome of British art. It’s certainly not the type of thing commanding record prices. I found the comparisons and historic echoes interesting and enjoyed seeing the Blue Boy when I was at the National Gallery to see something else. Would a pilgrimage just to see this have been satisfactory? Perhaps not.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 2.5/5

The Blue Boy on until 15 May 2022

Ali Cherri: If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed?

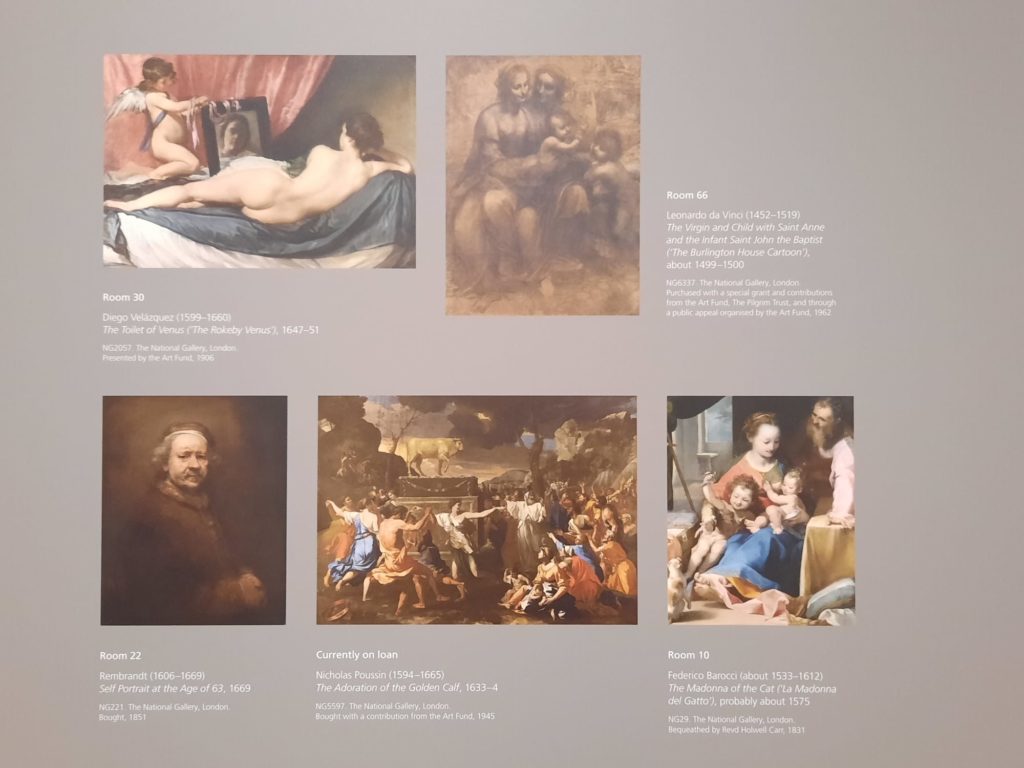

Now this is a very interesting concept for an exhibition. Ali Cherri is the current Artist in Residence at the National Gallery, and has taken archival research as the starting point for this intervention. In the Gallery’s archive, Cherri came across five accounts of works vandalised whilst on display here. The works include a Rembrandt and a da Vinci, so not exactly obscure. Cherri was struck by the way that popular accounts spoke of the works like they were people, the staff like surgeons, and adopted the language of healing.

The skill of the surgeon-conservators is such that today the naked eye cannot see the slashes, shots or traces of paint. But Cherri makes this history visible once more, underscoring that we are never quite the same after an act of violence. Each work has a Cabinet of Curiosity-style vitrine as a symbolic representation of its story. The assemblage for da Vinci’s Madonna and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist includes a 3D enlargement of the ‘bruise’ made by a bullet in 1987, as well as a sculpture of all-seeing eyes and a copy of the 1978 work Ways of Seeing. Poussin‘s Adoration of the Golden Calf, spraypainted in 2011, becomes a lamb which died of abnormalities at birth, taxidermied and triumphant on a plinth with a riotous frieze.

Cherri’s intervention is a very gentle one. The paintings under consideration are not in the same gallery as the cabinets of curiosity. You must seek them out if you want to see them in person. The links between vitrine and original work are not always straightforward, so the whole installation requires quiet contemplation. But the questions raised, about violence and our visceral reaction to artworks, are worth this consideration. I will be interested to see what else emerges from Ali Cherri’s time as Artist in Residence.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Ali Cherri: If You Prick Us, Do We Not Bleed? on until 12 June 2022

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.