Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965 – Barbican, London

A review of Postwar Modern at the Barbican Art Gallery in London. An exciting exhibition, its narrative about the impact of war, death and disruption is as relevant as ever.

Postwar Modern

Now this is an exciting exhibition from the Barbican. Maybe you recall this from a previous post, maybe you’re new here, but I love the Barbican most when they are doing things that I couldn’t see happening in any other London gallery. And this is a fantastic example.

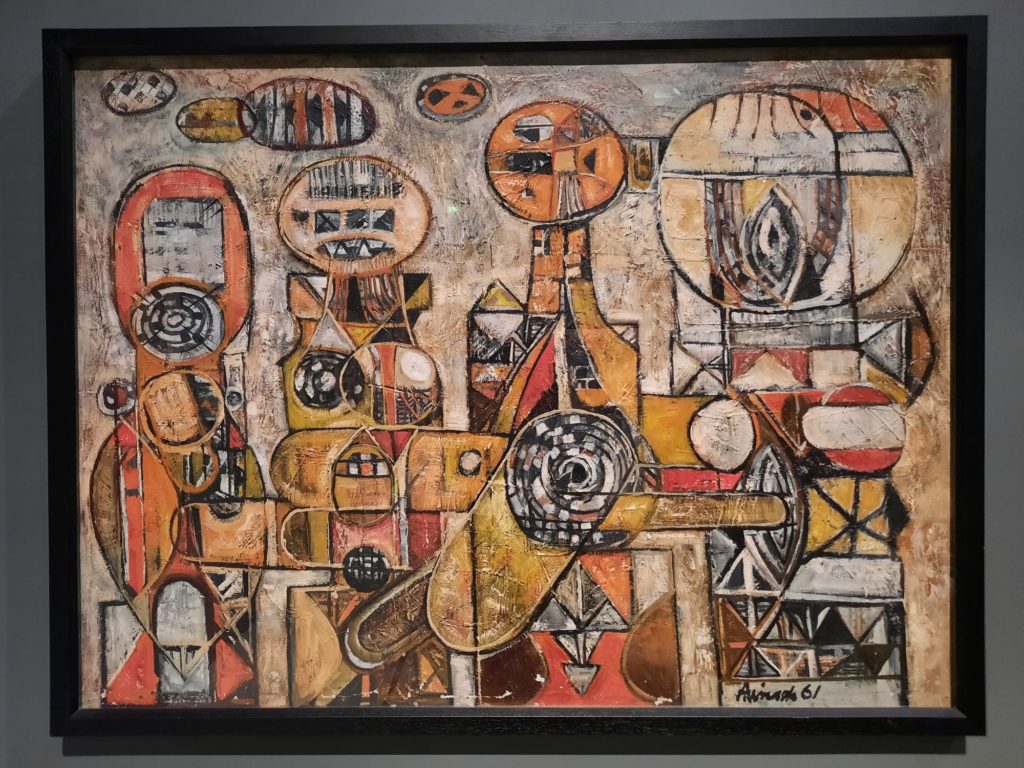

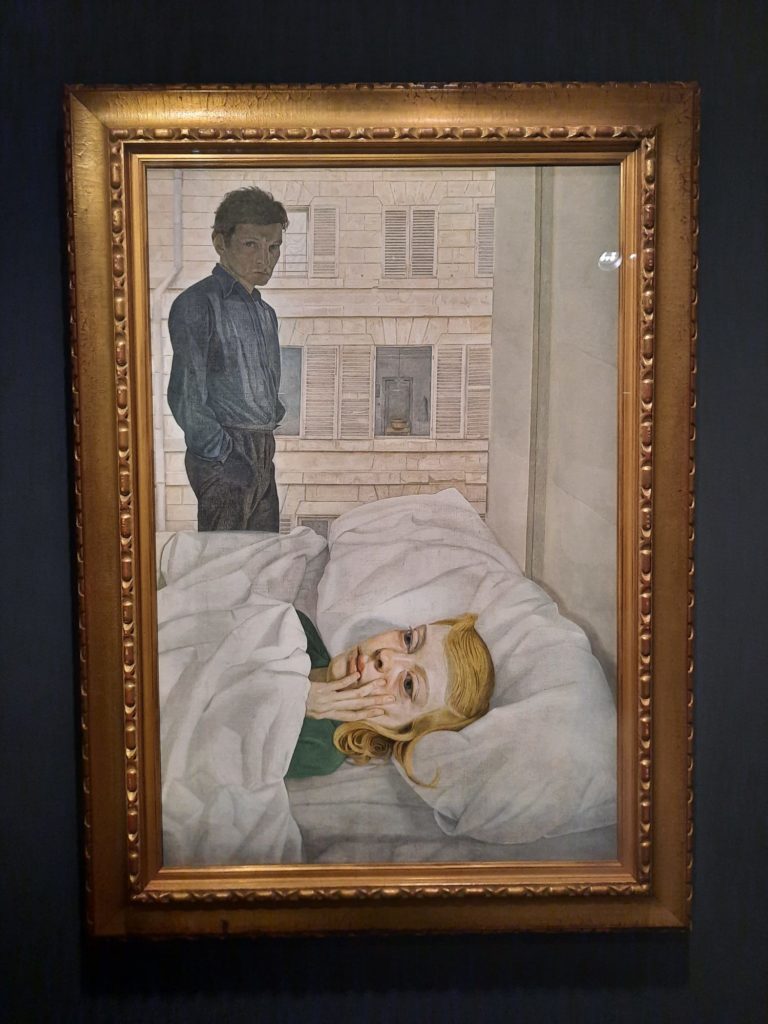

Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965 is quite simple on the surface. Art changed quite a lot in the years after WWII. There are a number of famous British artists associated with the period, including Bacon, Freud, Kossoff and others. And these artists are all here. But what got me so excited about Postwar Modern is the depth of the research into the subject matter. The curatorial team, led by Jane Alison, have not just pulled together the usual suspects. They bring to our attention artists who used to be well-known; artists who should be better known. Artists with very different experiences during the war. And artists who truly represent colonial Britain as was.

How on earth they ever knew to look for works by all of these artists I don’t know. Let alone where to actually find the paintings, many of which are from private collections. So first and foremost, Postwar Britain is a chance to really, truly understand the post-war British art scene. And not just the big hitters still making auction headlines today.

New Art In Britain

It is prescient, too, that this exhibition should have opened right around the time that a new European conflict was kicking off, marking the lives of more people. The artists among them will doubtless work through their experiences in their art in due course. In Postwar Britain we see how the generation of artists marked by WWII responded to the conflict.

There are artists like Lynn Chadwick or William Turnbull who were part of the armed forces. Others, like Franciszka Themerson, Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff who arrived as refugees. Eduardo Paolozzi who was interned as an enemy alien. Then there are other artists responding to the dreary grind of post-war Britain. Unlike the US, where the 1950s were all about modern appliances, prosperity and leisure, the 1950s in Britain were more about rebuilding and foodstamps. Not the stuff of dreams. And very well exemplified by a room dedicated to husband and wife Jean Cooke and John Bratby; hers the bigger talent, his the bigger jealous streak. Their unhappiness plays out on canvas like a kitchen sink drama. She is certainly one of the artists who should be better known.

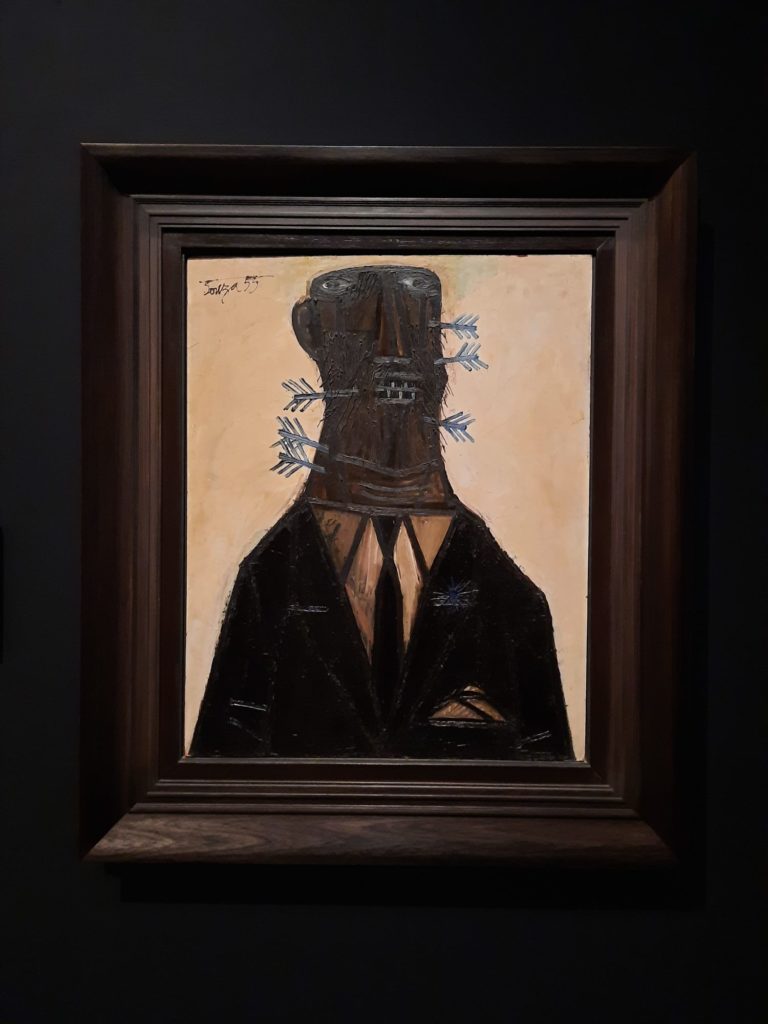

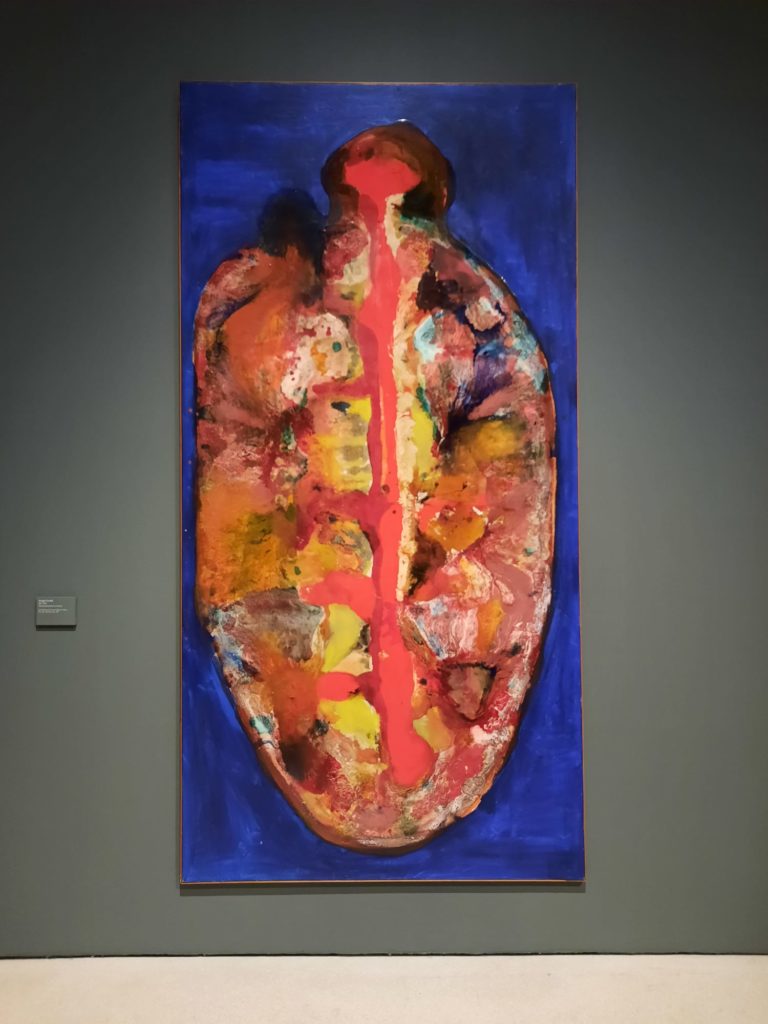

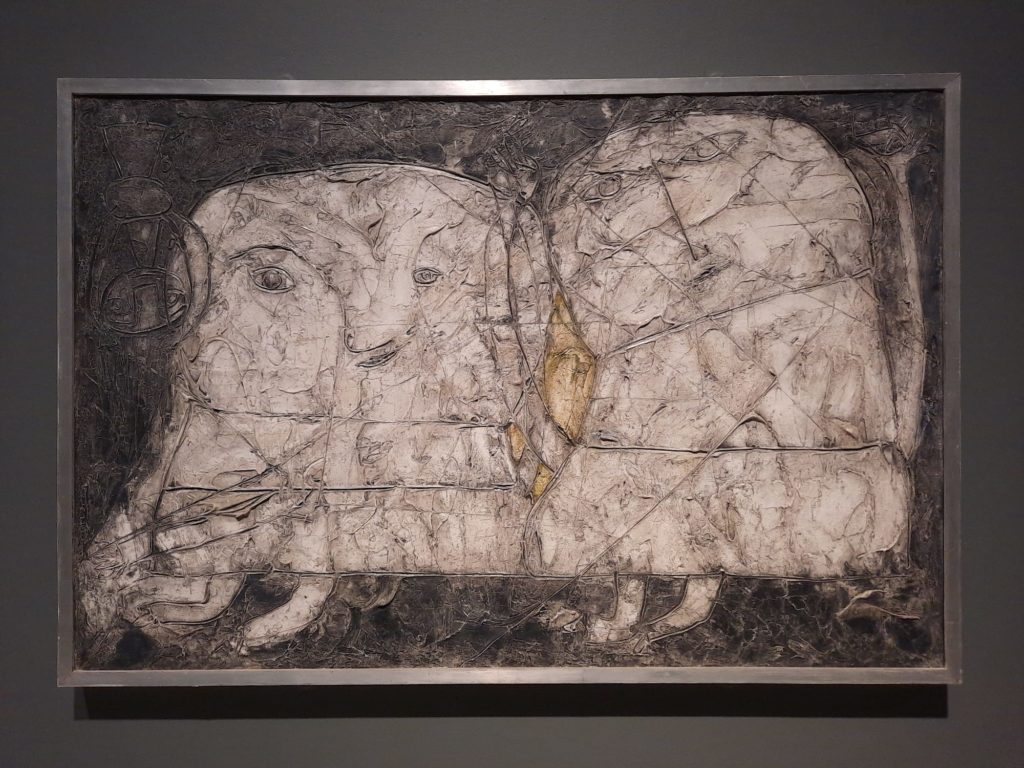

But across the board, this exhibition sets out very clearly how war gets into the psyche. There is an undercurrent of violence through many of the early works. Menacing figures loom over visitors. A couple of top notch works by F. N. Souza in the first room rethink traditional religious imagery of wounds and suffering. Figures are in flight, or flayed open. As we move through the exhibition there is a desire to break from the past and from all that unpleasantness, yet at the same time (as we see in some of the early Pop Art works), a cynicism about this shiny new future proffered to us.

The Post-War British Art Scene

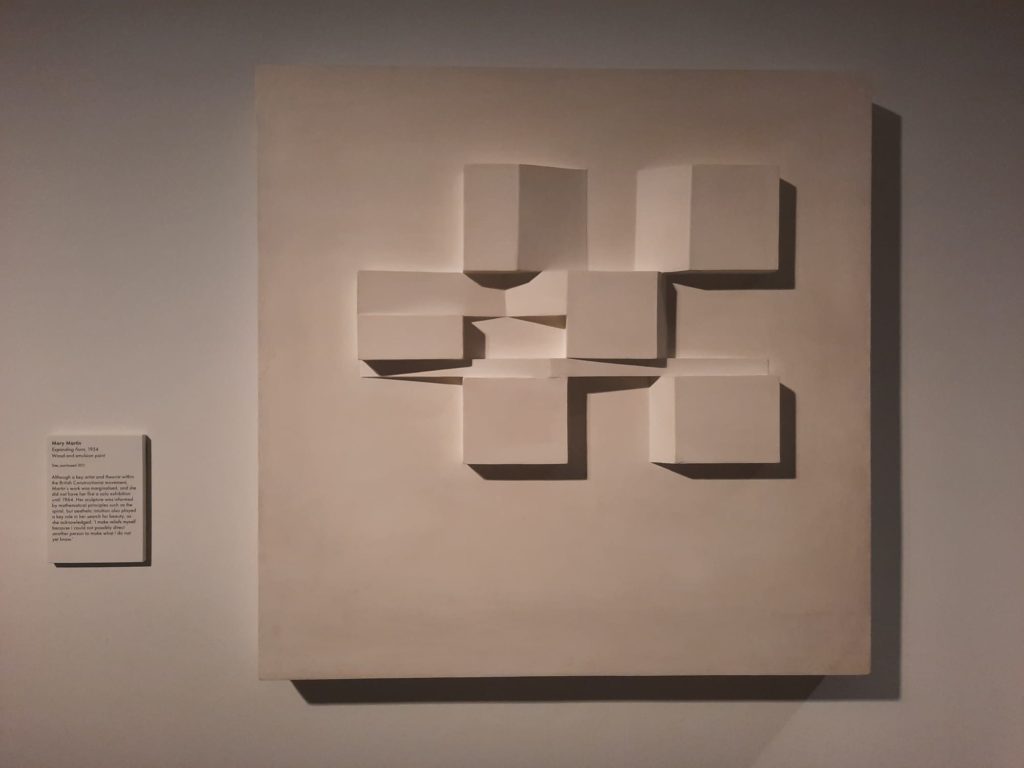

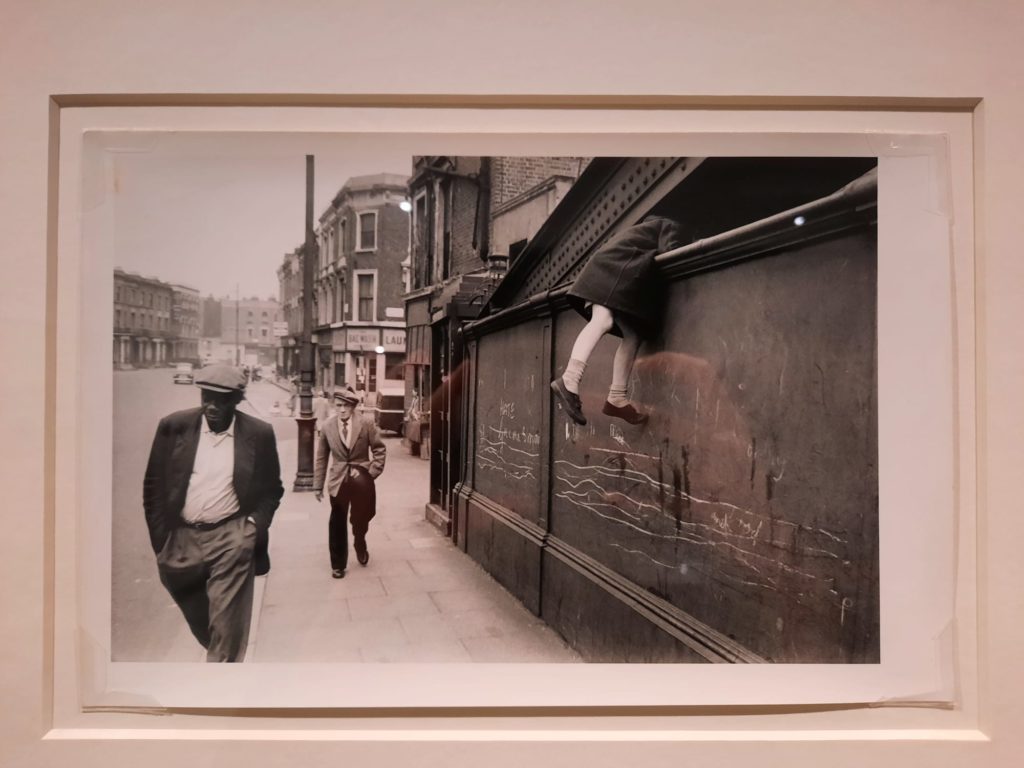

Another aspect of the excellent curatorial work behind this exhibition is how it is structured. Artists are placed in dialogue with one another; homosexuality hiding in plain sight in works by Bacon and Hockney, for instance. Or Shirley Baker’s photographs of community life in Hulme and Manchester juxtaposed with Eva Frankfurther’s paintings of unseen moments like waitresses resting in a cafe. By curating the exhibition in such a way, there is plenty of space for plurality. We understand that there was not one Post-War British Art, but many scenes, and connections, and schools, and styles. As well as media – the exhibition encompasses paintings and sculpture of course, but also kinetic art, performance art, ceramics, textile design, photography, and more.

I really liked this tendency in the exhibition, which again I think goes back to the incredibly thorough research and preparation. The period in question is at least around 60 years ago. Plenty of time for human minds and the art historical narrative to select, prune and fit things into an agreed shape. By deliberately including overlooked artists, female artists, artists not born in Great Britain, as well as some astonishingly unexpected works such as Sylvia Sleigh’s portraits of her lover Lawrence Alloway dressed as his alter-ego Hetty Remington, our expectations of what this period was all about, or even what type of modern we’re talking about, are subverted. Our minds are opened back up to everything that British art had to offer in the post-war period. The trends that developed into today’s art as well as those promising ones which didn’t.

Final Thoughts On Postwar Modern

This really is an excellent exhibition and a labour of love. You would have to tour the length and breadth of local art galleries in the UK, as well as several people’s private collections, in order to have this opportunity again. It’s definitely easier to grab a ticket and get down to the Barbican now!

And as you can tell from this review, I got a lot out of it. There were some really smashing works on view. I particularly liked those by Souza which I mentioned already, and a couple by William Scott. Plus some stunning studio ceramics by Hans Coper, Lucie Rie and the like. But much more than any one work, I enjoyed really seeing what British art in the post-war period was all about.

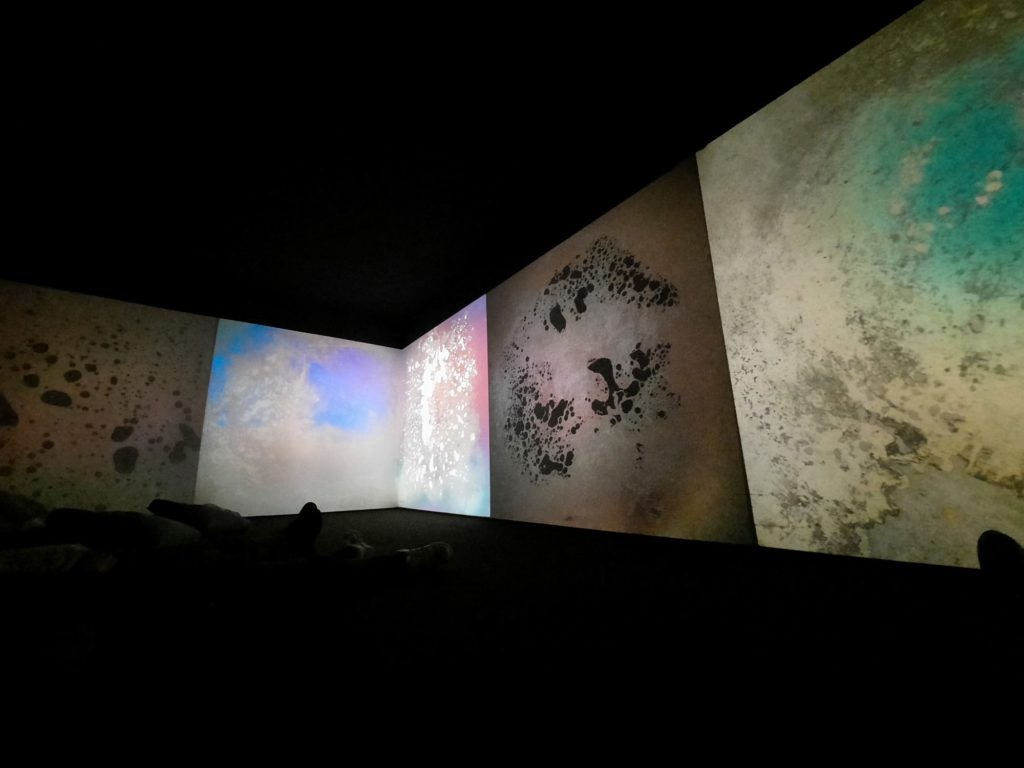

My advice is to leave plenty of time to see everything on view, and then to lie down in the final room which has a kind of light show by Gustav Metzger, footage of whose auto-destructive/performance art where he burns canvases with acid on the South Bank is in an earlier room. The light show is more hypnotic, and is a good opportunity to digest all you’ve seen before you move downstairs and discuss the exhibition over a drink at the bar.

To bring us back to some earlier points, it is a shame that so much powerful, transgressive, beautiful, thoughtful art had as its source (or one of them) such a difficult time in human history. That many of these artists suffered first hand and channeled this experience into their art. Yet it is also a testament to art’s power to transform, to endure, and to communicate. I hope that today’s artists have the opportunity to look back in future years and see how their own experiences shifted the dial.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965 on until 26 June 2022

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

One thought on “Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965 – Barbican, London”