Anglesey Abbey, Lode

A description of a visit to Anglesey Abbey near Cambridge. This National Trust property primarily tells the story of an Anglo-American family’s tenure in a site steeped in history.

Anglesey Abbey, Home To 1st Baron Fairhaven

As stately homes go, the story of Anglesey Abbey is quite an interesting one. It’s not like a Blenheim Palace or a Wilton House or an Althorp which have been in the same family for generations. The house itself has been around for centuries, but the story it tells today is that of the family who lived there in the 20th Century. Anglesey Abbey is located a short distance from Cambridge and can be visited easily by car and less easily by public transport. It is under the care of the National Trust, who do an excellent job of maintaining and interpreting it.

But back to that 20th Century family. Urban Hanlon Broughton was a young English civil engineer who found himself in the town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, in 1895, modernising the drainage system. There he caught the eye of wealthy heiress Cara, daughter of Henry Huttleston Rogers. Rogers had made a fortune in oil and was Director (later Vice President) of J. D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. Cara and Urban married and had two sons, remaining in the US until 1912.

Once back in the UK Broughton served as an MP and undertook a lot of philanthropic work. In recognition for this Broughton was awarded a peerage, but died in 1929 before it could be officially bestowed. His eldest son Urban Huttleston Broughton (known as Huttleston) thus became 1st Baron Fairhaven. It’s an unusual peerage, being based on a location in the US and not UK. When Huttleston died in 1966 his brother Henry became 2nd Baron Fairhaven, and the title now sits with Henry’s son Ailwyn.

Anglesey Abbey, however, is not a family seat. The brothers had bought it in 1926 because it was good for shooting and conveniently located. They had an agreement that the first to marry would sell his share to the other, and thus it became solely Huttleston’s in 1932. When he died in 1966, he left it to the National Trust, who still care for it today.

A Modern(ish) Home

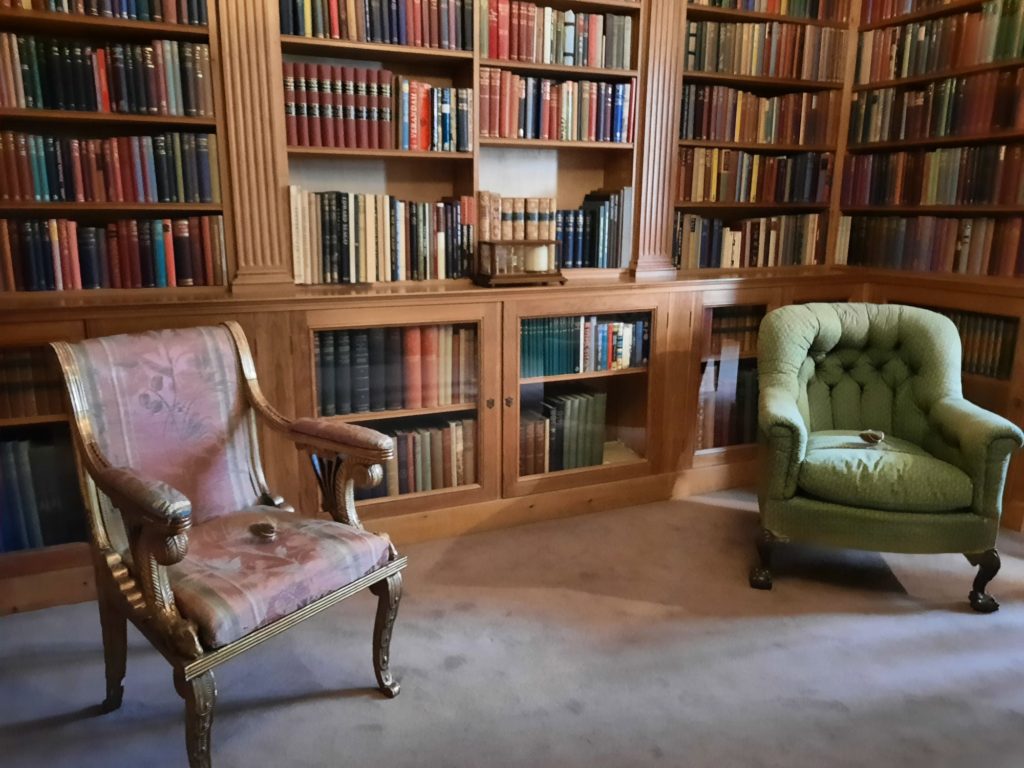

The brothers had purchased Anglesey without much thought of creating something of it. It was only once Huttleston was the sole owner that he began to take the house and its gardens seriously. For someone who came to it late, he managed to build a pretty good collection of art and objects, and some very nice landscaping which has since been further developed.

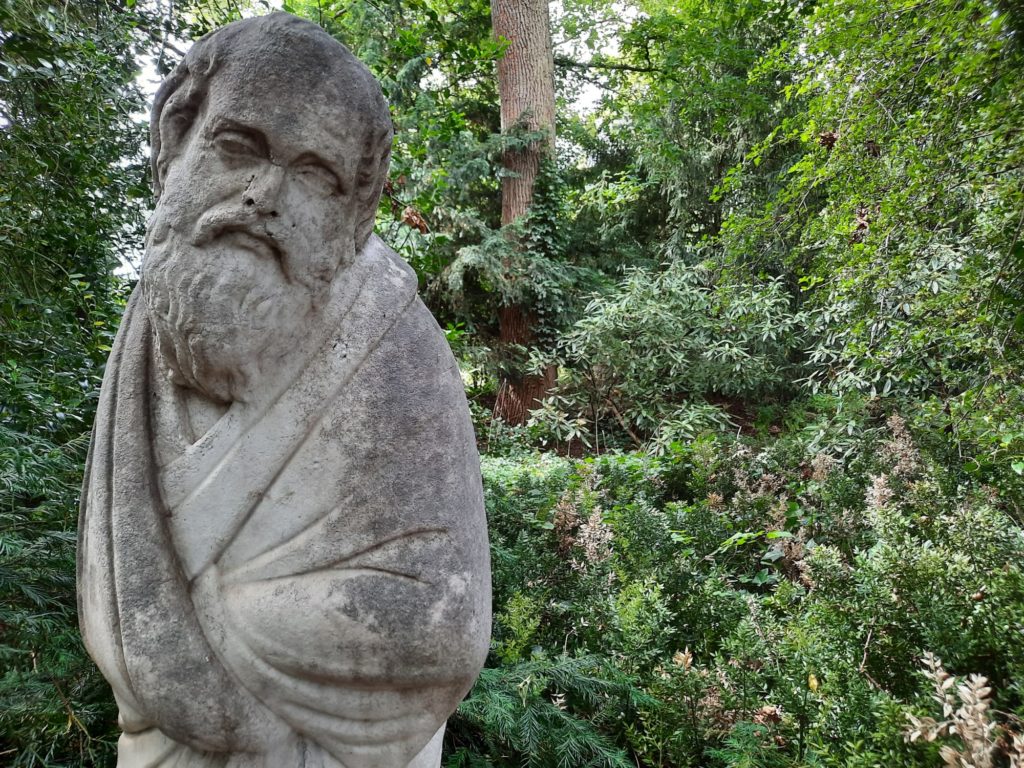

In terms of the garden, plenty of Lord Fairhaven’s design remains. It’s a mix of formal and more naturalistic styles. There are the sort of secluded alleys and vantage points with carefully placed sculptures that you would expect to see in the grounds of a stately home. But also more relaxed spaces.

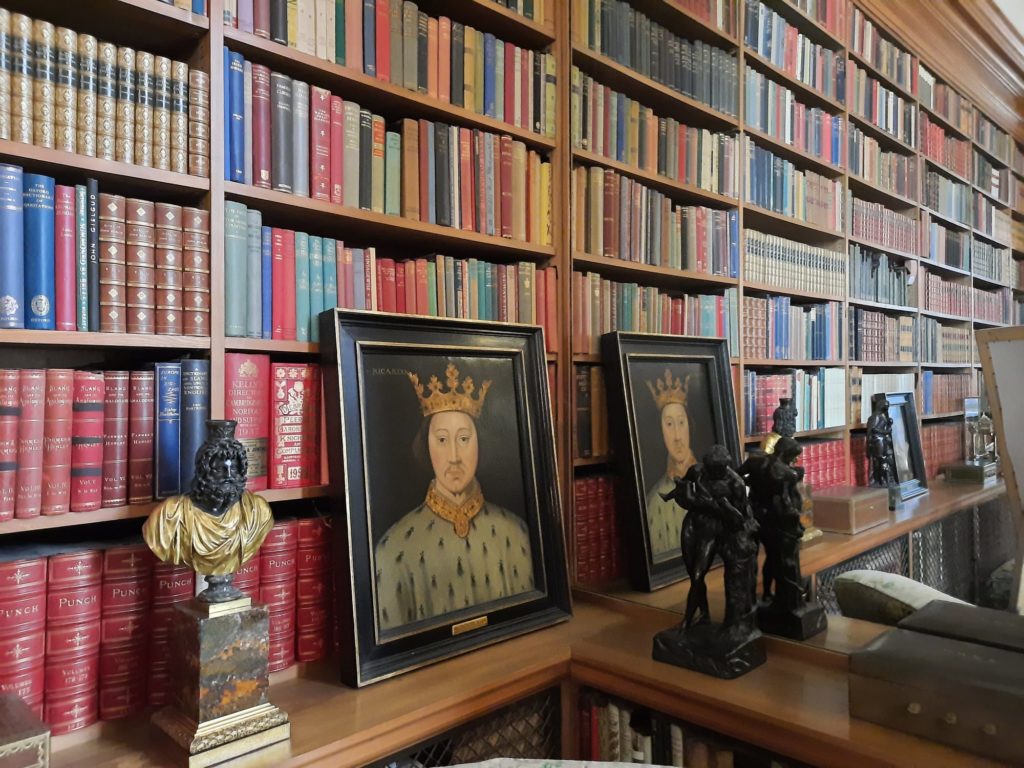

And the collection, according to the National Trust, is ‘world class’. Partly this is a result of timing. Lord Fairhaven was able to buy at a time of crisis for many of Britain’s aristocratic families. The impact of WWI and high death duties had decimated finances across the country. Houses were sold or demolished, and their contents sold at auction. Lord Fairhaven thus amassed a good selection of paintings, furniture, religious statuary, silver, porcelain, and all the rest. The primary reason for me going to Anglesey Abbey was actually to see some of their art collection. So it still draws visitors in today.

Yet there is something nicely modern about the house nonetheless. I think it’s in the fabrics. Unlike a lot of fancy country houses which are all traditional silks and tapestries, Anglesey Abbey has a lot of mid-century printed fabrics in the curtains and upholstery. It reminded me of visiting Ted Heath’s house in Salisbury last year – very firmly of its time, and not a time that is usually preserved for posterity.

A Historic Place, Too

Underneath all the mid century fabrics and art collection, there is a very historic heart to Anglesey Abbey. The clue is in the name. It’s not just an affectation, this was a literal abbey until the Reformation. Or to be precise, it started life as a 12th Century hospital, before becoming an Augustinian priory in 1236. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries a Cambridge lawyer purchased it to reuse building materials for his own Madingley Hall. A Jacobean house was built here circa 1600 by the Fowkes family, and it passed through various hands. In fact sometimes it was not lived in by the owners at all, but leased as a farmhouse.

A lot of the medieval structures and outbuildings survived for quite some time, in fact until the Victorian period. Then owner Reverend John Hailstone drew careful sketches of all of them, before undertaking a big renovation project and tearing them down. A bit unfortunate, but still the best clues to the original layout, which have been used as recently as 2020 to inform archaeological digs.

Lord Fairhaven expanded Anglesey Abbey once more, adding an art gallery wing, library and gabled windows. He carefully preserved what was left of the historic fabric of the building, which at this point was basically an arched ceiling in the dining room and some historic stonework. Lord Fairhaven also purchased nearby Lode Mill, an 18th Century mill which had at some point been converted from grinding corn to grinding cement. Lode Mill is closed currently to undertake repairs, so I only saw the exterior on my visit to Anglesey.

The Visitor Experience

Visiting Anglesey Abbey today, it’s remarkable just how much it does feel like a historic stately home. Especially given the unusual path that it took to get there. Others, like Wilton House for instance, were sold straight after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, turned into family homes, and have been lived in by the same family ever since. Anglesey Abbey, on the other hand, effectively took four centuries to get to the same place. And yet today, thanks to Lord Fairhaven, visitors enjoy formal gardens and a home with an impressive art collection, as well as the sort of activities and exhibitions that the National Trust create for their properties.

There is enough at Anglesey Abbey to more than fill a day out. Where you start and what you see depends on your interests. I was a little short on time. So I focused on the house and the section of garden between it and the entrance. I’ll just have to go back another time to see the rest! I very much enjoyed how welcoming the garden was. There are plenty of spaces to sit and enjoy the views, and even these sort of wooden constructions at one point which encourage you to lie back and contemplate the clouds like John Constable. You can bring your own food and drink in or there’s a cafe on site, so I would encourage visitors to make a day of it and leave enough time for a pleasant pastoral lunch.

The house takes between 30 minutes and an hour to visit, depending on your pace. A visitor host greets and orients you at the front door, and there are more guides throughout. Otherwise it’s up to you to wander and enjoy. There are a lot of interesting historic details, for example a ceiling moulded from historic originals. And when I visited there was a temporary trail focusing on works by Constable in the Anglesey Abbey collection.

Final Thoughts On Anglesey Abbey

I think what’s interesting about Anglesey Abbey is the way that, given the means, you can make a credible stately home despite a late start. From Augustinian priory to today’s impressive home, Anglesey Abbey has not had the easiest journey. Many different owners have left their mark on it over the centuries. Yet, despite the Fairhavens buying the estate for practical purposes, you can see the labour of love that it became.

Anglesey Abbey today is thus a nice space for local residents and visitors from further afield. It’s not entirely easy to get to from Cambridge without a car, and so isn’t what I would call open to all. But for those with the means and some time to spare, it’s a nice outing.

And as far as National Trust and similar properties go, I found it an interesting middle ground. Its fortunes haven’t varied quite as dramatically as Sutton House, for instance. But it’s not frozen in time, either, like all those houses that did stay in one family. It speaks to a certain time in English history when new sources of wealth encountered, and in some cases preserved, tradition.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.