Edvard Munch: Masterpieces From Bergen – The Courtauld, London

A review of Edvard Munch: Masterpieces From Bergen, a dissection of an artist’s exploration of painting style through one collection.

My Favourite Tiny Exhibition Space

Since its reopening, I think the Courtauld Gallery might have become my favourite place for temporary exhibitions. Or one of them, at least. And what I love about it is that it’s tiny. Just two rooms, off the Courtauld’s Post-Impressionist gallery. In fact there’s quite an amusing activity where, if you stand near the exit, you can watch people wander out and then wander back in again, explaining to the security staff that they thought there were more rooms.

So what is it about a tiny exhibition space that makes it so good? Well I talked about it a bit already when I went to see Van Gogh. Self Portraits. It has a lot to do with the fact that, when an exhibition is so small, it’s like an enforced go-slow. You know you don’t have hundreds of works waiting for you. You won’t be feeling museum fatigue by the time you finish. Instead you have to savour each work because there just aren’t that many of them!

In this case, for Edvard Munch: Masterpieces from Bergen, there are eighteen. Just eighteen works, all from the first half of Munch’s career, and all coming from the same Norwegian collection. The other great thing about the Courtauld’s exhibition space is that everything is new, so they are hung and lit to perfection. So come on then, let’s wander tranquilly through the inner spaces of Munch’s mind as we explore this exhibition.

Edvard Munch: Masterpieces From Bergen

So why Bergen? Well, it’s thanks to Rasmus Meyer. An industrialist and mill owner, Meyer hailed from Bergen in Norway. He wanted to assemble a collection of artworks by Norwegian artists, with the aim of one day creating a public museum. After his death, his children gifted the collection to the city of Bergen, and today Meyer’s collection is the heart of the KODE Bergen Art Museum.

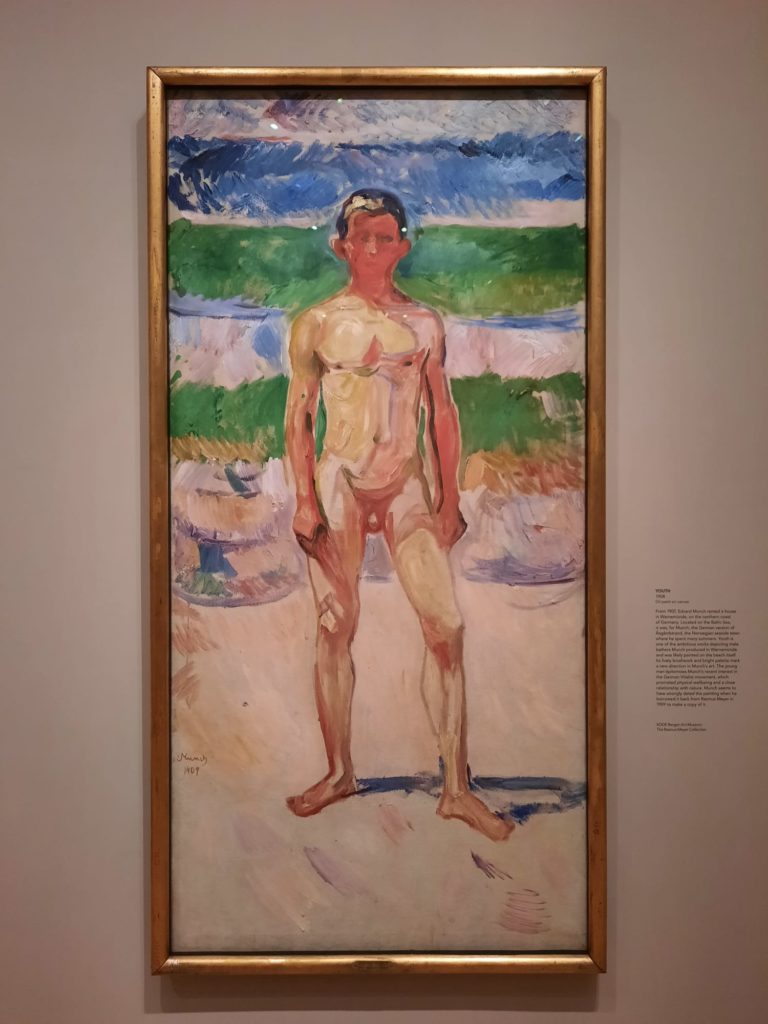

Meyer didn’t simply collect Munch’s work, however. He knew Munch personally and bought paintings from him directly, assembling a comprehensive selection spanning his major paintings. The works on view therefore take in his early days dabbling in Impressionism and Pointillism, the beginnings of a radical shift in style, and his later years as an artist of growing international fame.

I visited Bergen several years ago but did not go to the KODE Bergen Art Museum. I don’t remember why now – I suspect I was more taken at the time with the city’s Hanseatic history. I’m now wondering what else I missed! Perhaps a return trip to the city nestled in fjords is in order?

Early Years

The exhibition is hung in largely chronological order, so charts Munch’s artistic development clearly. Each work has a thoughtful label with more information on the people and places depicted, or the work’s reception. To be honest the first room is a little surprising at first glance. Could this Pointillist street scene, so devoid of substance, really be by Munch? Or this Impressionist portrait of his sister at the beach, all sunlight and swift brushwork?

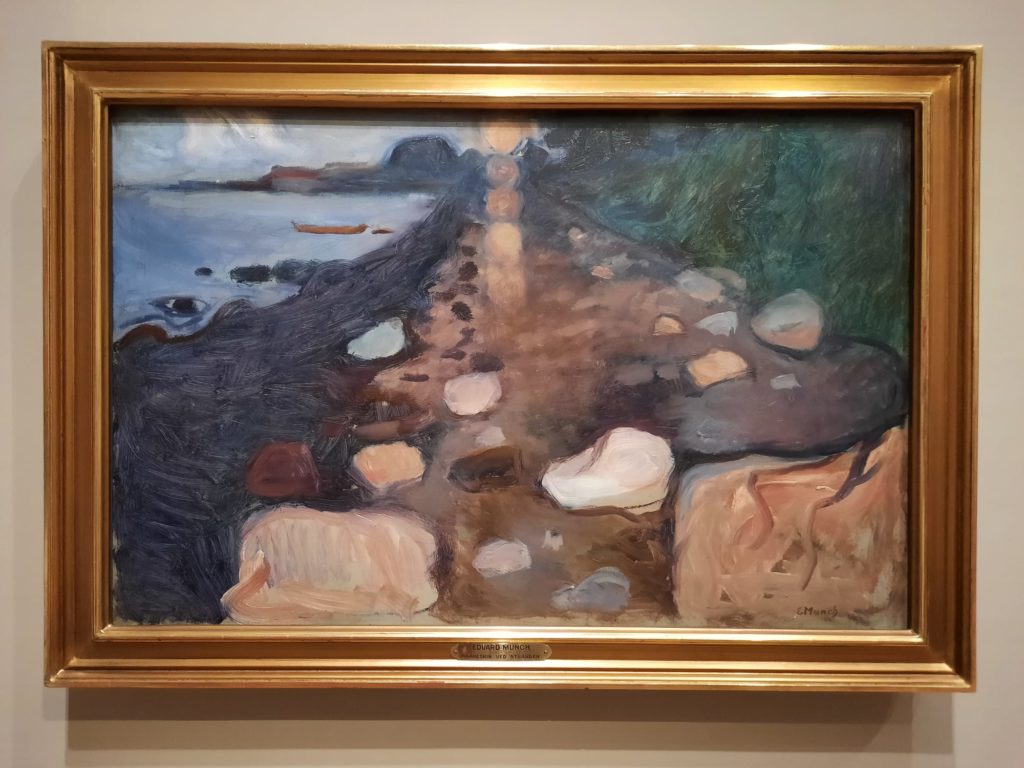

But a few paintings in, we start to see the Munch we know emerging. Shadows loom. Colours deepen. In one painting, the moon is refracted, duplicating itself down the canvas. It’s now less about trying out what those French artists were doing, and more about expressing feelings directly to us, the viewers.

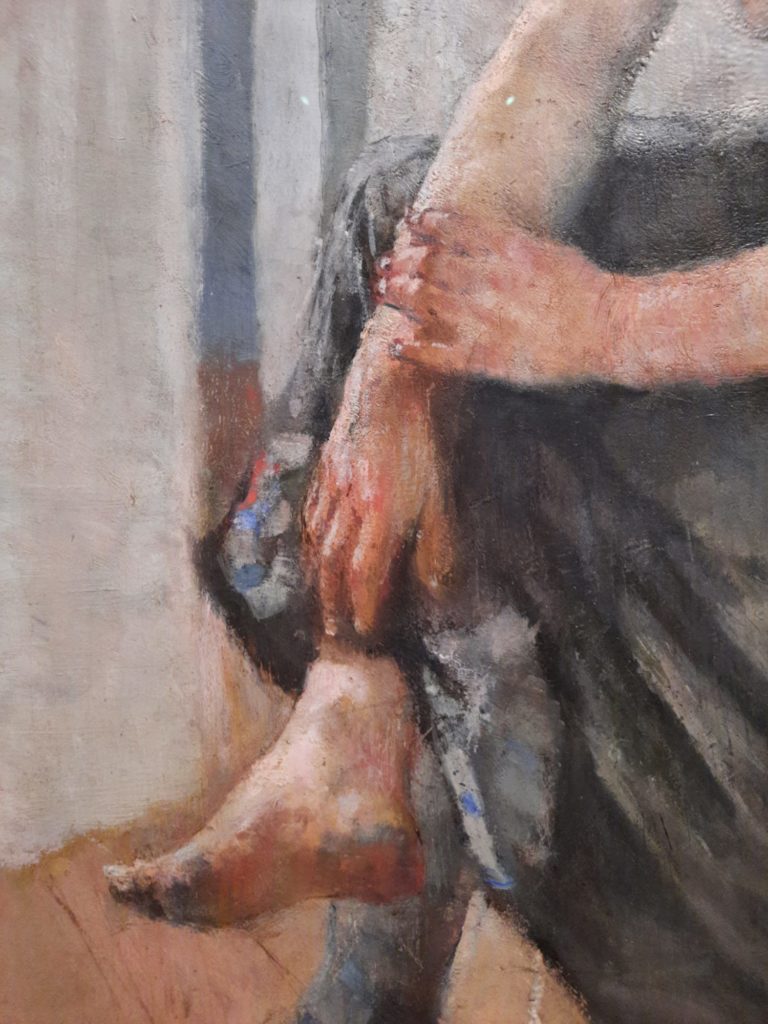

My favourite work in this first room is another portrait of Munch’s sister. Summer Night. Inger on the Beach was painted in 1889. It marks a transition between the old and the new. The depiction of his sister Inger is still naturalistic. But the landscape around her is softened, the boulders depicted in colours that look more like Munch’s later palette. This is more about conveying a mood than a passing effect of light. Munch has found his voice.

The Frieze Of Life

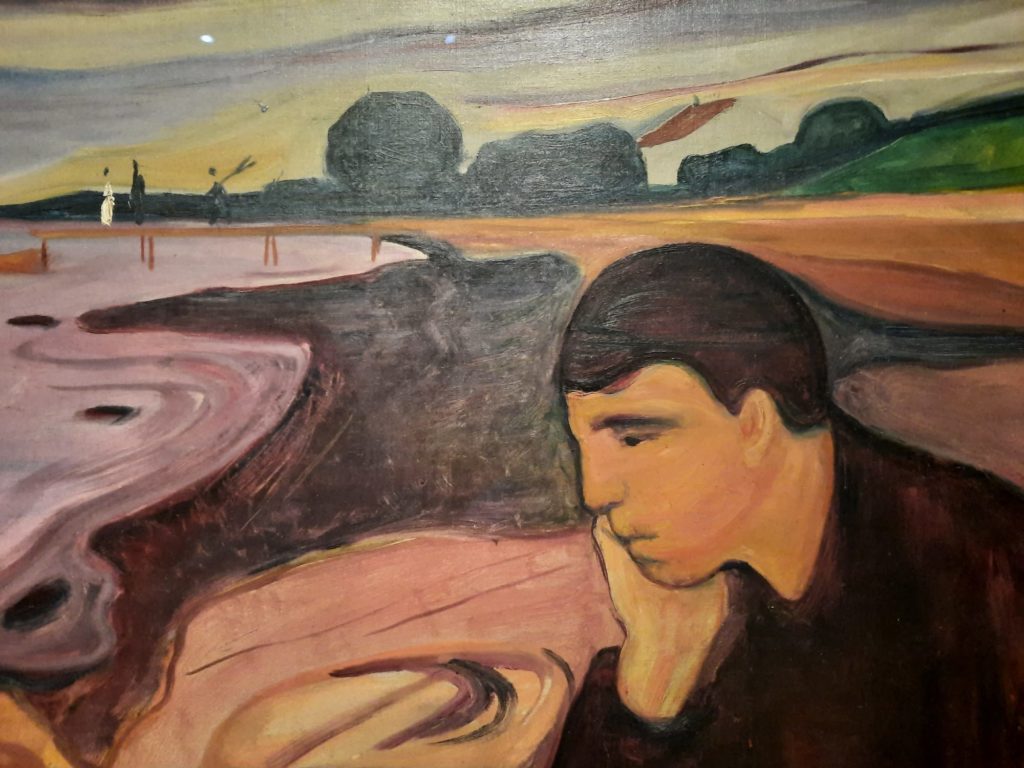

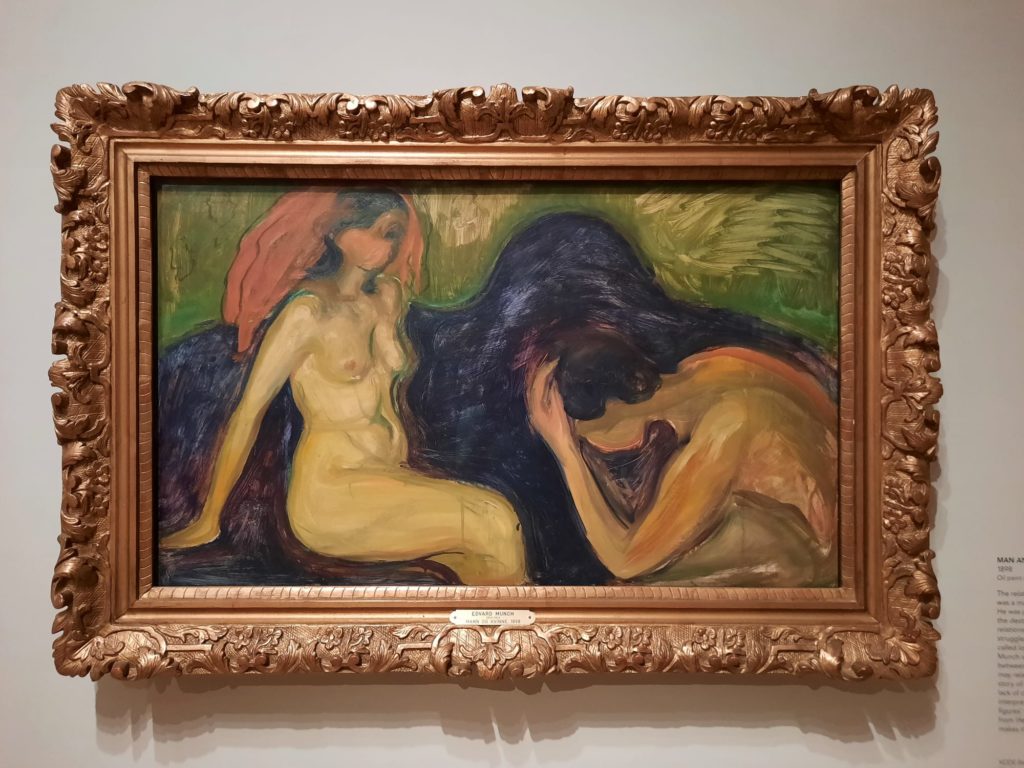

In the second room of the exhibition, several of the works come from Munch’s series The Frieze of Life. This was, as the title suggests, an exploration of moments throughout a life. Munch infused it with the existential preoccupation with modernity and all its attendant anxieties that is best exemplified by The Scream. City streets become anonymous, confusing spaces. Women assert a new role in the world, and men must adjust. Industrialisation, urbanisation, sickness, love – all of life is here.

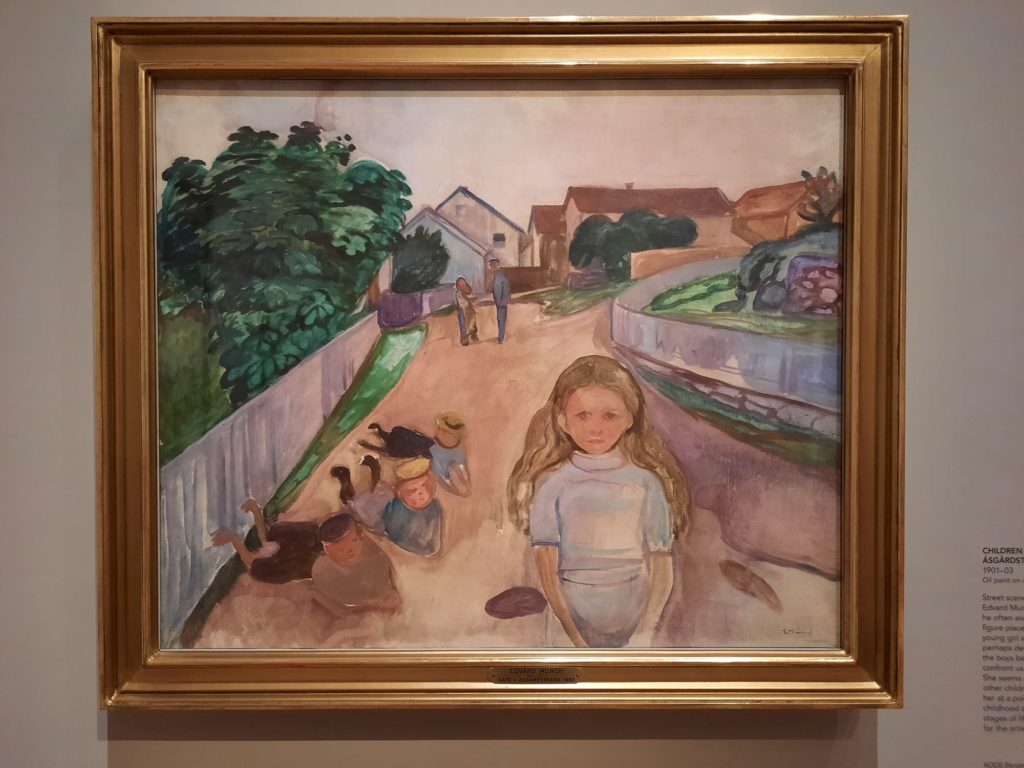

It’s interesting to see how Munch structures this exploration of modern life. His works tend to be very direct. A little girl stares out of the canvas at us on more than one occasion. Compositions are cropped in interesting ways, figures often very close to the foreground. Faces are anonymised – missing pupils, noses, mouths. Meyer selected some top-notch works, which really demonstrate why Munch is such an important modern painter.

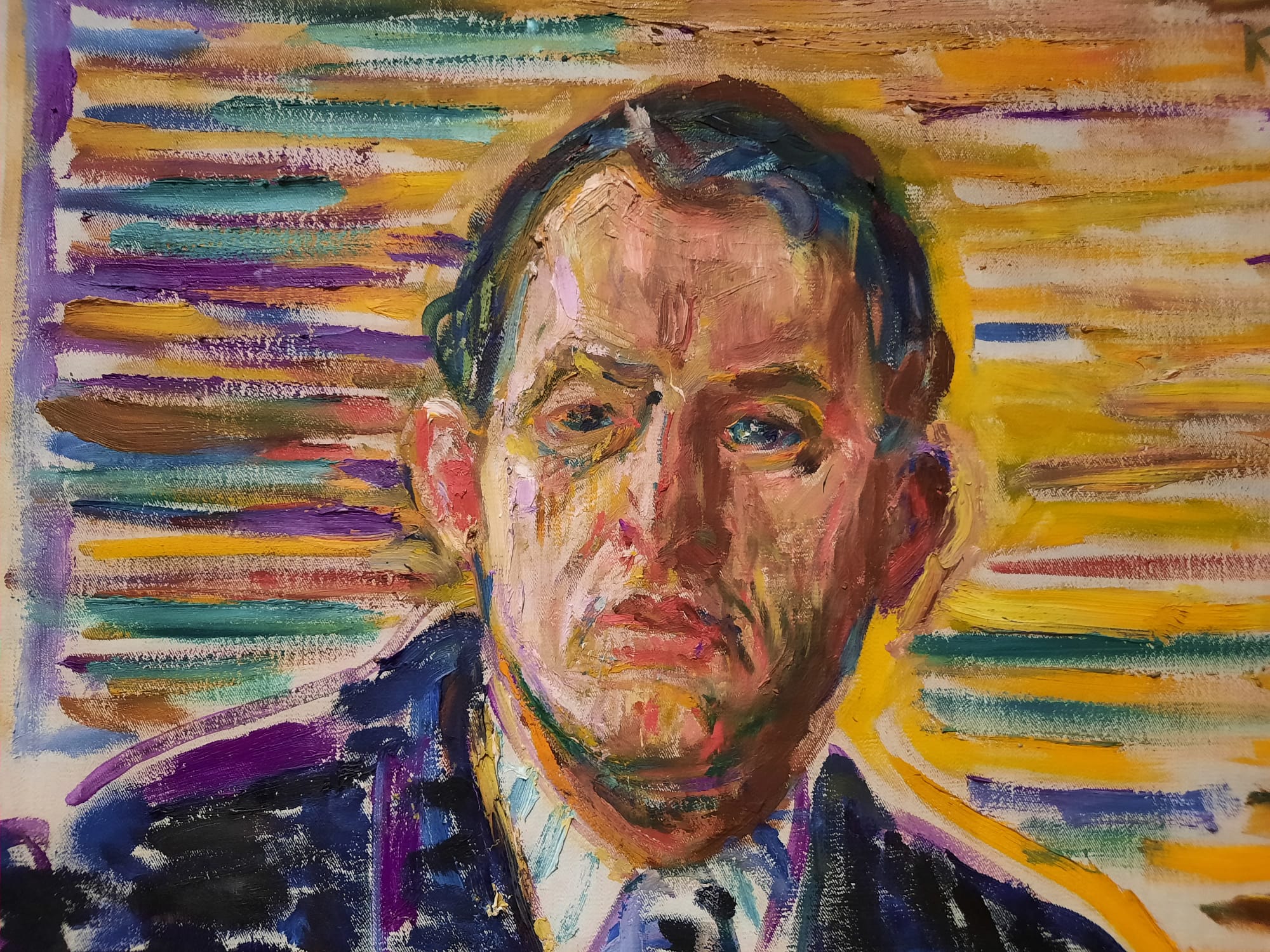

For me the absolute star of the show is a self-portrait from 1909. In 1908 Munch had suffered a nervous breakdown and sought treatment in Copenhagen. He set up a studio at the clinic, and painting became an important part of his recovery. This self portrait is extraordinary. It’s made up of the most unexpected colours – purples, blues, yellows, blacks. He depicts his face carefully, while his body and the background disappear into looser and looser patches of colour. It’s almost like his early Pointillist attempts: if you’re close to the canvas you’re looking at individual blocks of colour, but as you step away it resolves itself into a dignified self portrait. More than that, an assertion of self.

It reminded me of the last time I was in these galleries, looking at Vincent Van Gogh’s very similar statement of identity and artistic vision after a period of poor mental health. The power of art summarised in a handful of extraordinary canvases.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 5/5

Edvard Munch: Masterpieces From Bergen on until 4 September 2022

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

I love this review and wish so much to have seen the exhibition. His development is so clear, his technique so interesting and the results so emotional.