Reframed: The Woman In The Window – Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

A review of Reframed: The Woman in the Window, an excellent thematic exhibition on for a few weeks more at the Dulwich Picture Gallery

Reframed: The Woman In The Window

Dulwich Picture Gallery, it’s been a while. The last time I was here was for Unearthed: Photography’s Roots. There was a Helen Frankenthaler exhibition in the middle which I sadly missed. And now I’m back for Reframed: The Woman in the Window.

This is an interesting thematic exhibition. It’s about a single motif in art, that of the woman in the window, and explores what it has meant across time and geographies. What has the subject of the woman in the window signified about attitudes to women? About art? About agency? What do the artworks tell us about the women in their windows, and what do they tell us about ourselves?

As I said, an interesting premise. Definitely worth a trip to Dulwich on a hot summer’s day to check it out. And the fact that it is curated by Dr. Jennifer Sliwka of King’s College London, who also curated interesting shows like Monochrome at the National Gallery, was a further draw for me. So without further ado let’s take a look at Reframed and get to know these women in the window.

An Almost Universal Motif

The premise of Reframed: The Woman in the Window is, as I explained above, the exploration of this motif. A sort of who, when, why, what of the subject of the beautiful woman looking out of the window. And it turns out this subject has some history to it. The oldest work on view is a loan from the British Museum, a Phoenician carved ivory panel dated 900-700 BCE. Greek vases and other historic works bolster these ancient origins, while the first work in the exhibition makes the point that it is the Old Master version, painted by Rembrandt and the like, which forms the basis of our mental image today. The earlier works led up to this, and subsequent representations have branched off from it.

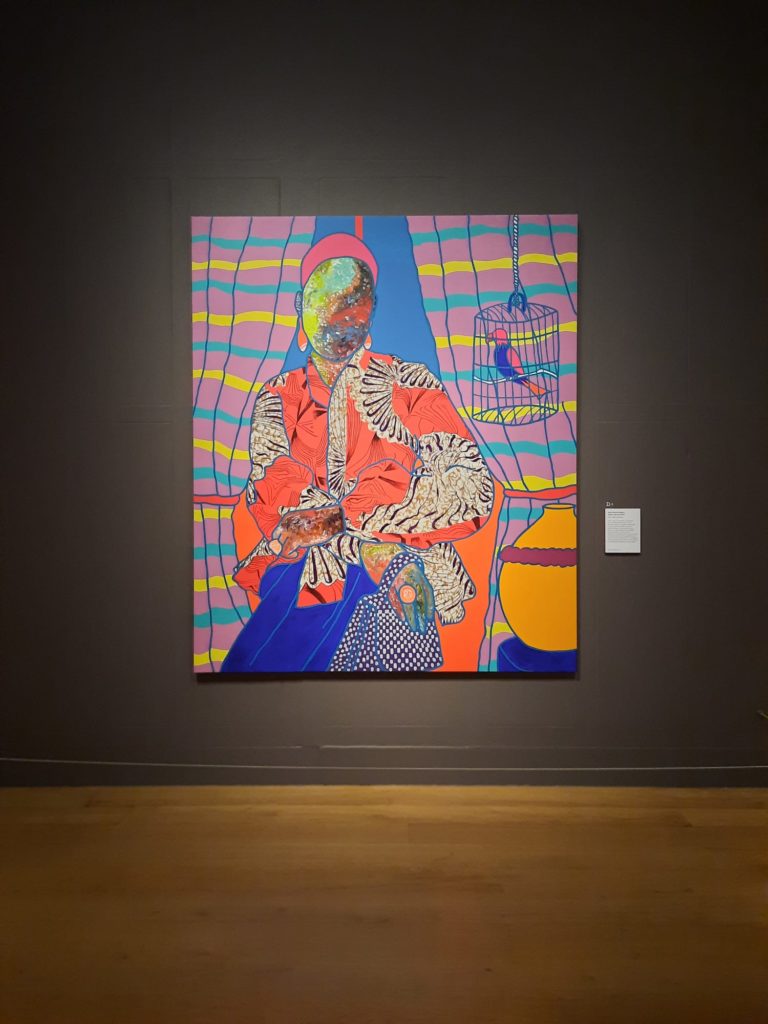

So it’s no surprise that there are several 17th and 18th Century examples. By Rembrandt, of course, but also a depiction of a Black woman attributed to Metsu, and a coquettish woman in grisaille by Louis-Léopold Boilly. Right from the outset, however, Sliwka makes her point about art historical references manifest by including contemporary works. There’s a bright and bold painting by Cameroonian Ajarb Bernard Ategwa. And a photograph by Tom Hunter from 1997, which depicts a young mother in a squat receiving an eviction notice, but directly references an antecedent by Vermeer.

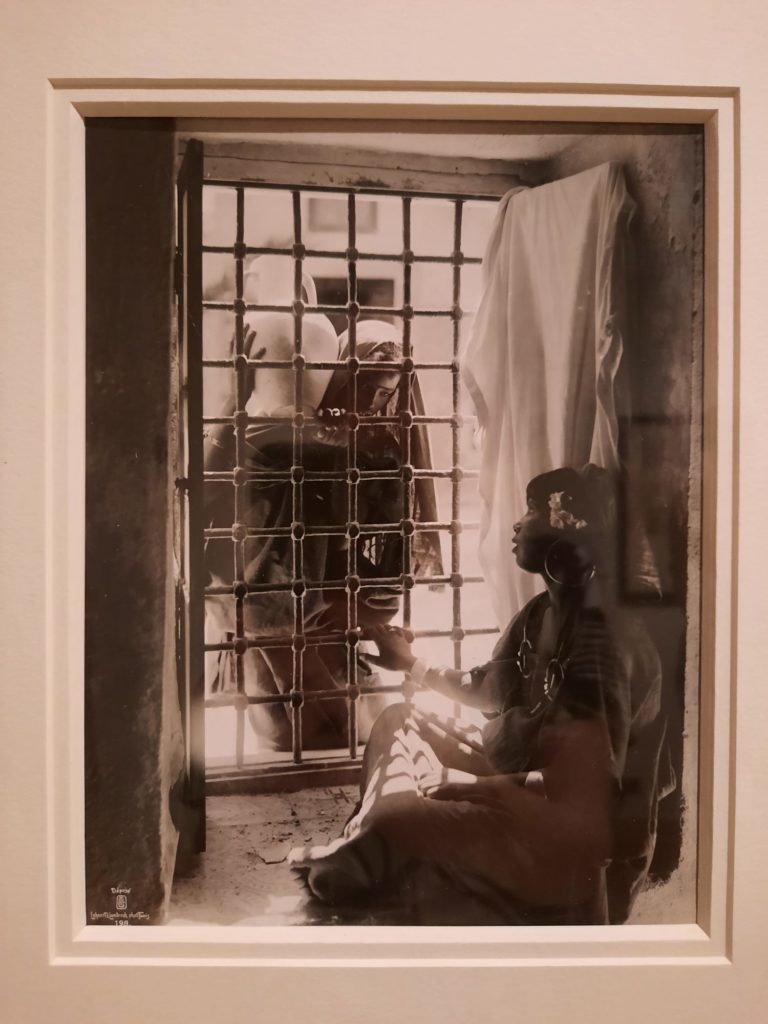

So it’s an art historical argument clearly stated and sufficiently proven as we move to the next room and explore different themes by which our women in their windows can be grouped. There are the religious depictions of Mary and saints, the window functioning as a window to heaven. The muses, inspiring male artists as they sit and stare contemplatively. Sliwka pulls no punches, by the way, in calling out shitty behaviour on the part of some of these male artists towards their muses. Picasso towards Françoise Gilot, for instance. Or Degas towards a starving sex worker who he treated, if not inhumanely, then degradingly. Turns out it’s not all beautiful pining when you’re the woman in the window.

Expanding Horizons

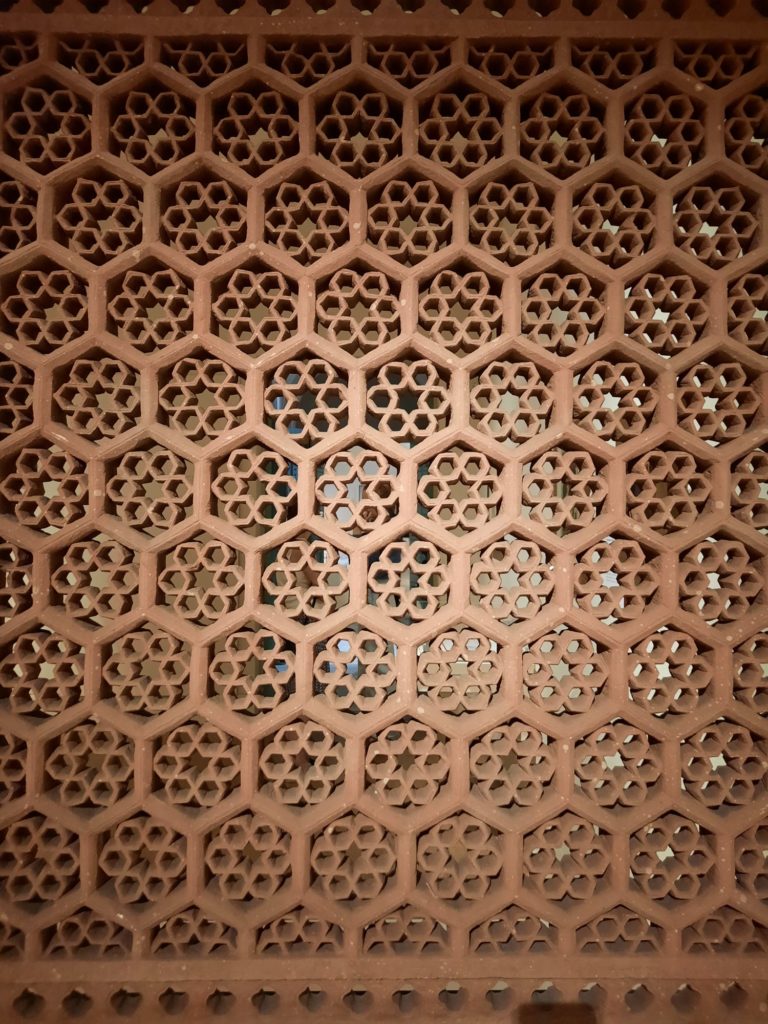

Something I particularly enjoyed about Reframed was the curator’s attempt to take in a full survey of artistic traditions on her chosen subject. A section on windows as screens, for instance, brings in Eastern artists and subjects, as well as a literal sandstone screen from Mughal India. Later we see a reasonable smattering of non-Western artists exploring the subject in their own ways.

The most interesting decision in my mind, however, and one which made me question my own unconscious biases, came about halfway through the exhibition. The Dulwich Picture Gallery has its own mausoleum, an atmospherically-lit space halfway down its length. In the mausoleum Sliwka has placed Isa Genzken’s 1990 Fenster, an outline of a window in concrete and steel. The mind-blowing revelation? This is the first artwork by a female artist. We are halfway through the exhibition now and I had not noticed that I’d been looking exclusively at women depicted by men. Does that mean my feminist credentials have been revoked?

I think this goes to show the impact of a strong curatorial vision. It’s not just selecting works around a theme and bringing them together. There’s an art to pacing the exhibition, grouping works and punctuating them with statements you want to make. This is a great example, and really brings the subject matter to life.

Artistic Variations

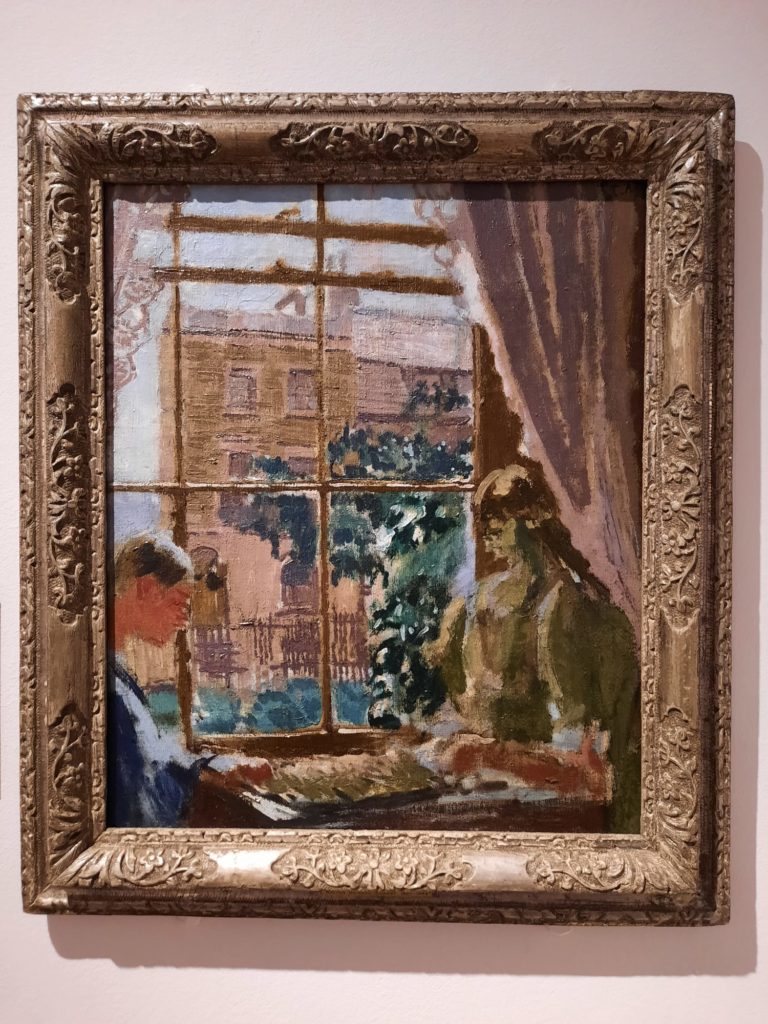

As we head into the second half of the exhibition, there is thus a better balance of work by male and female artists. There’s also a fascinating variety of works on view. There are photography pioneers (Clementina Viscountess Hawarden). Found object assemblages (Peter Blake’s Girl in a Window, 1962). A lightbox with a contemporary image of a Canadian domestic interior overlooking a port. Walter Sickert painting his landlady.

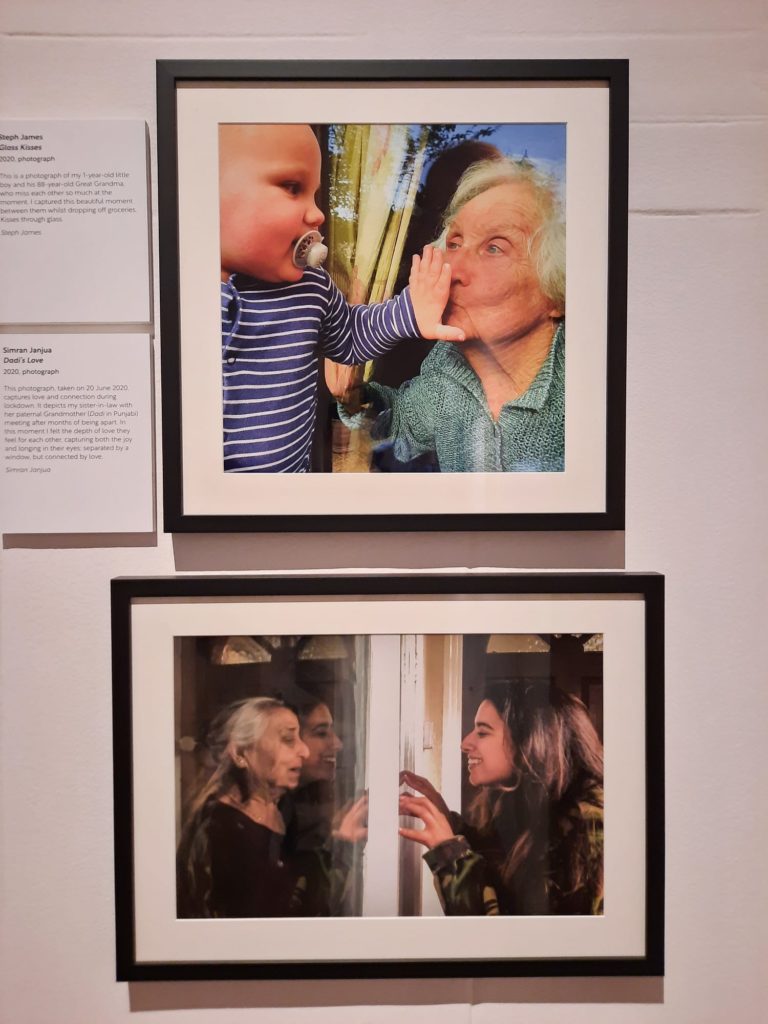

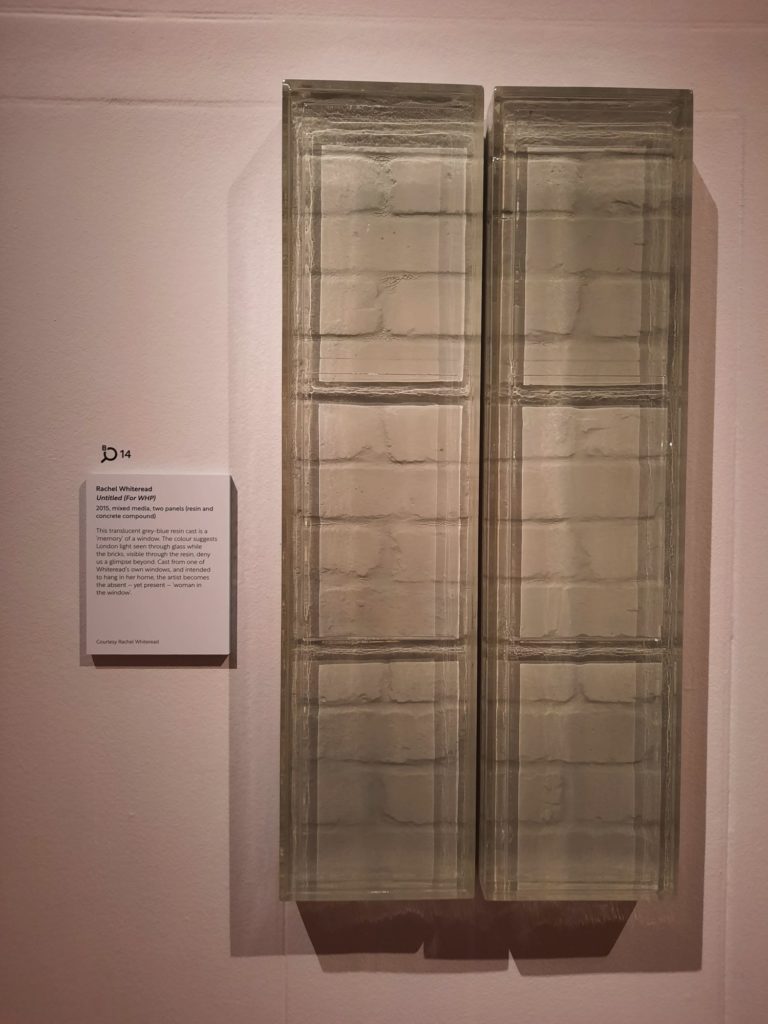

The final room bookends the first quite nicely. For a start, it’s all female artists (including a couple of Covid photographs which bring the motif firmly up to date). But it also showcases some of the ways that the subject of the woman in the window has evolved since it was cemented in the 17th Century. Rachel Whiteread creates the memory of a window. For Louise Bourgeois, a window is a lifeline to the outside world during a period of reclusion. Marina Abramovic documents a performance in which she changed places with a worker in Amsterdam’s red light district, who attended an opening while Abramovic took her spot in a window. The woman in the window is no longer passive. The woman in the window is the artist herself, negotiating her space in the world by upending expectations about what this age-old motif can and should be.

Final Thoughts on Reframed: The Woman In The Window

I really think this is an excellent exhibition. And this is from a few points of view. I think it’s a technically very good display of curatorial talents first and foremost. Sliwka has taken a topic, broken it down, and brought the most interesting bits back together. It’s also fascinating from an art historical point of view. It takes a subject which is easy to overlook or to take at face value, and makes us think it through. Finally it’s also just a pleasing exhibition to visit. There’s a broad range of art on view. It’s never boring. I guarantee you will discover at least one artist you’re not familiar with. Really top notch.

So all that being said, I give it a broad recommendation to most museum and culture fans. The only downside is that, because I left it to quite late in the run to get to the Dulwich Picture Gallery and see it, you don’t have long to do the same. Only two weeks in fact. My humblest apologies – I won’t complain as I know what the alternative is like (ahem, Covid) but London really does keep you busy trying to see everything that’s on!

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 5/5

Reframed: The Woman In The Window on until 4 September 2022

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.