William Kentridge – Royal Academy, London

A review of William Kentridge at the Royal Academy. The RA’s large galleries give these thoughtful and creative works the space they deserve.

William Kentridge

Before seeing Sybil at the Barbican earlier this year, William Kentridge was an artist about whom I knew very little. Perhaps you are in the same boat? Let me explain a little before we get into the exhibition of his work currently on at the Royal Academy. Born in 1955, William Kentridge is a South African artist known for working across a range of media. Sybil actually illustrates this versatility quite well. The evening included Kentridge’s short film The Moment Has Gone, joined by live accompaniment and chorus. Kentridge’s film-making technique is unusual, in that it is based on capturing constantly revised drawings on a single piece of paper, rather than a clean sheet per image. The chamber orchestra Waiting for the Sybil included, as well as music, projections, hand painted backdrops and costume designs by Kentridge.

So hopefully that starts to paint a picture. No medium seems to be off limits, with Kentridge equally talented in all. And this talent showed itself early: I don’t know of many artists who have a catalogue raisonné of their juvenilia (works produced during his youth). Kentridge was born to a Jewish family in which both parents were lawyers representing people marginalised by the apartheid system. This family history granted him something of a ‘third party observer’ status within South African society, and gave him the ability to step back and see critically the apartheid era’s structures and atrocities.

Still living today in Johannesburg, Kentridge’s art has, over the years, reflected South Africa back to itself. As well as his own practice Kentridge has served as director or art director on a number of collaborative projects. He furthermore speaks eloquently and humorously about art and artistic practice, for instance in this 2010 video for the New York Studio School.

With this background in hand, let’s now continue on to look at the Royal Academy’s retrospective of William Kentridge’s work.

Royal Academy Takeover

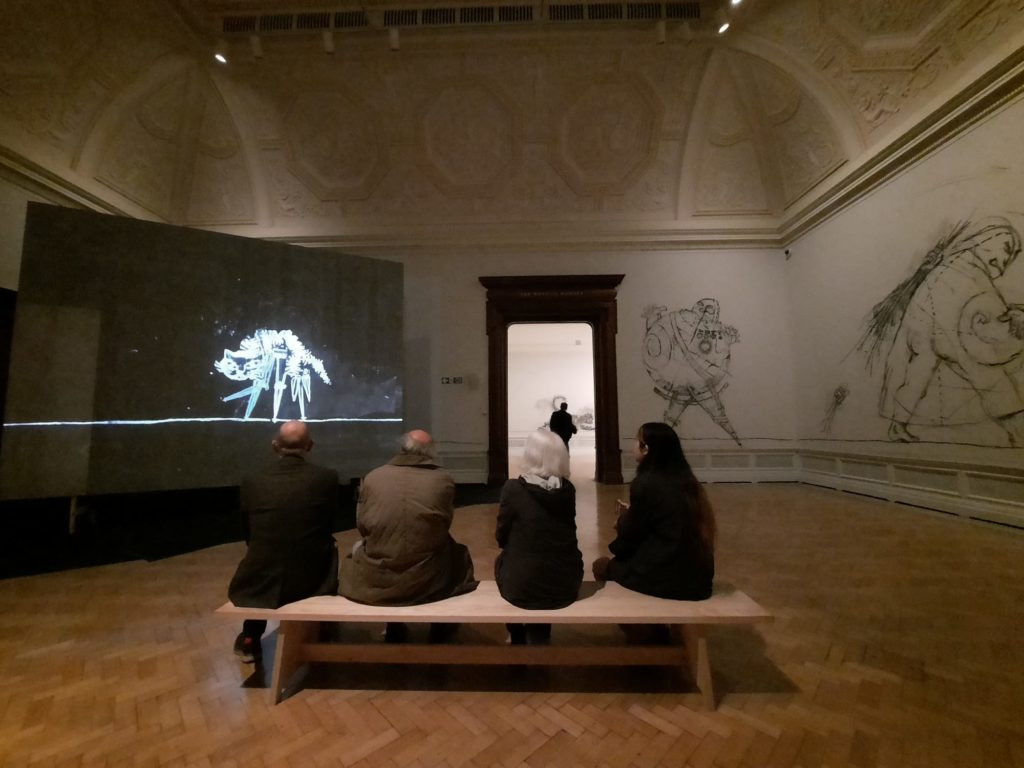

So with my basic knowledge of William Kentridge’s work, I headed off recently to the Royal Academy to see their retrospective. As we’ve discussed previously there are several different exhibition spaces at the Royal Academy: William Kentridge is on in the main first floor galleries, where the RA host their Summer Exhibition. This is a good choice. Kentridge’s works are often large, and here they have space to breathe without being too squashed in.

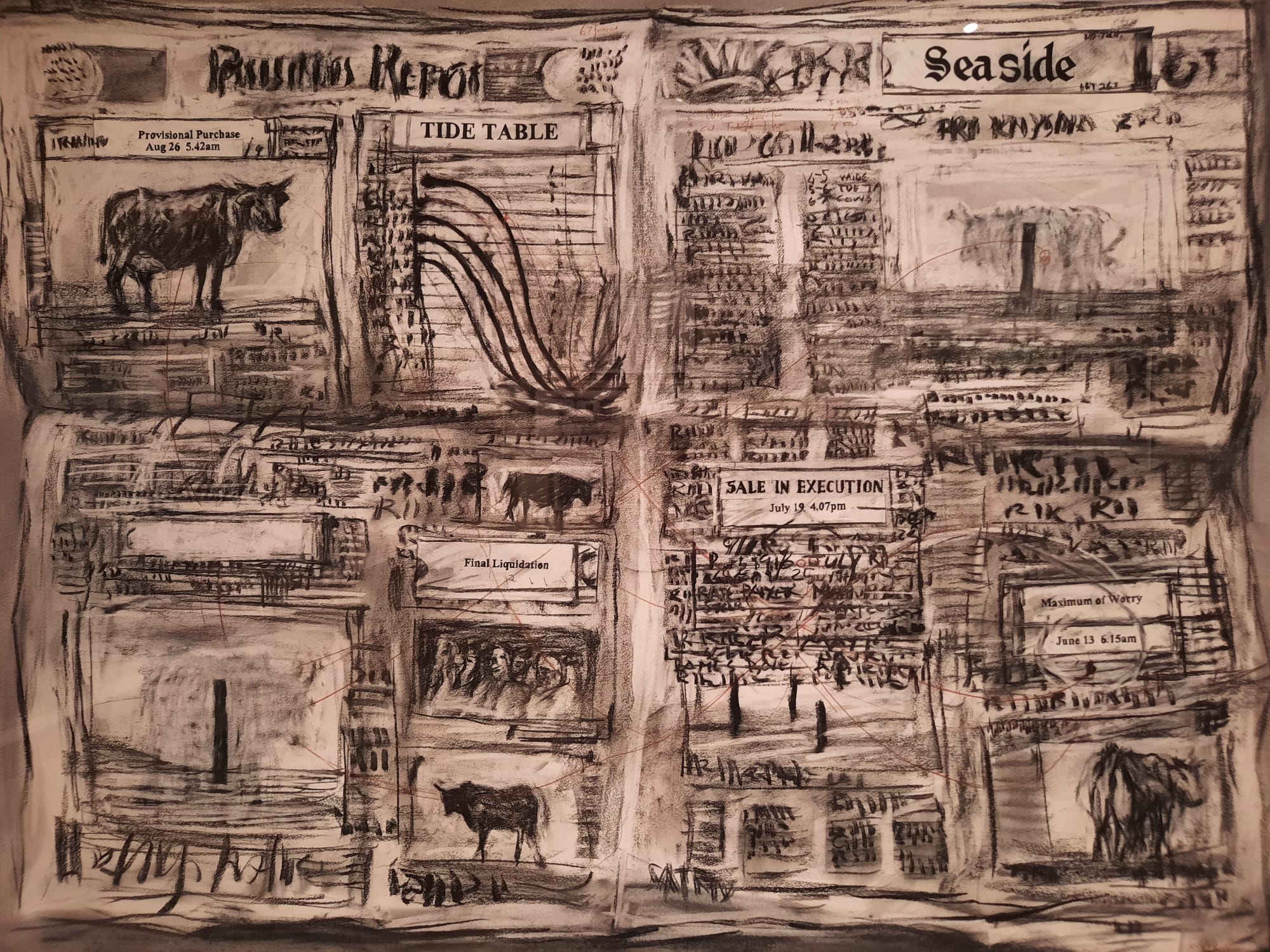

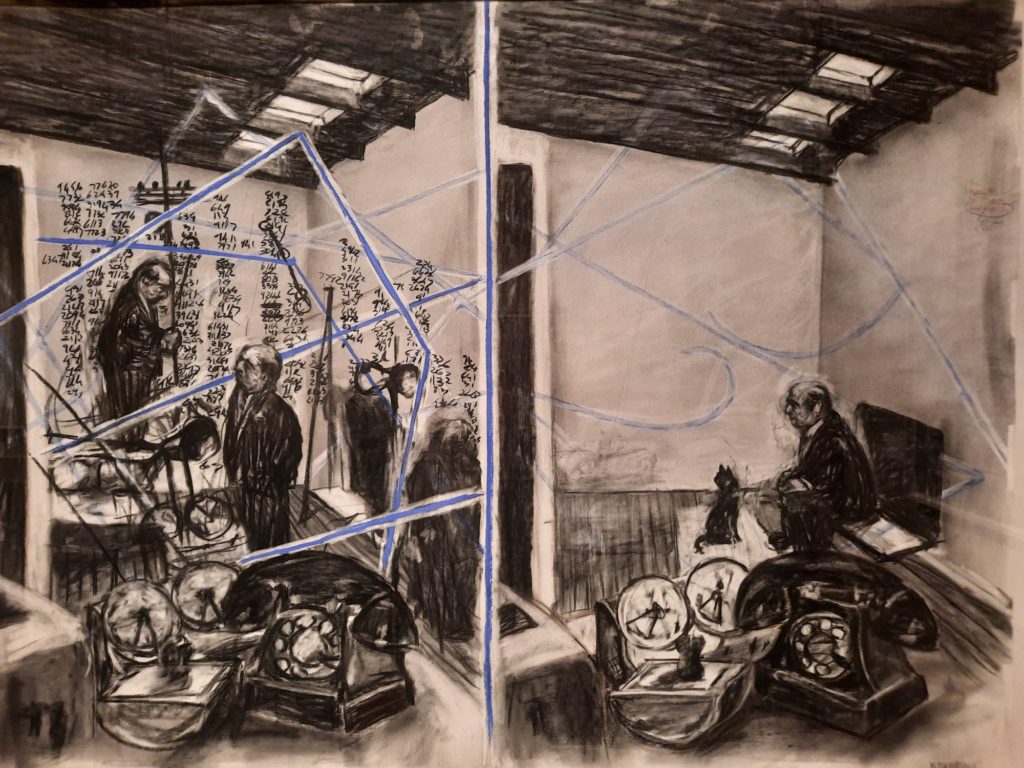

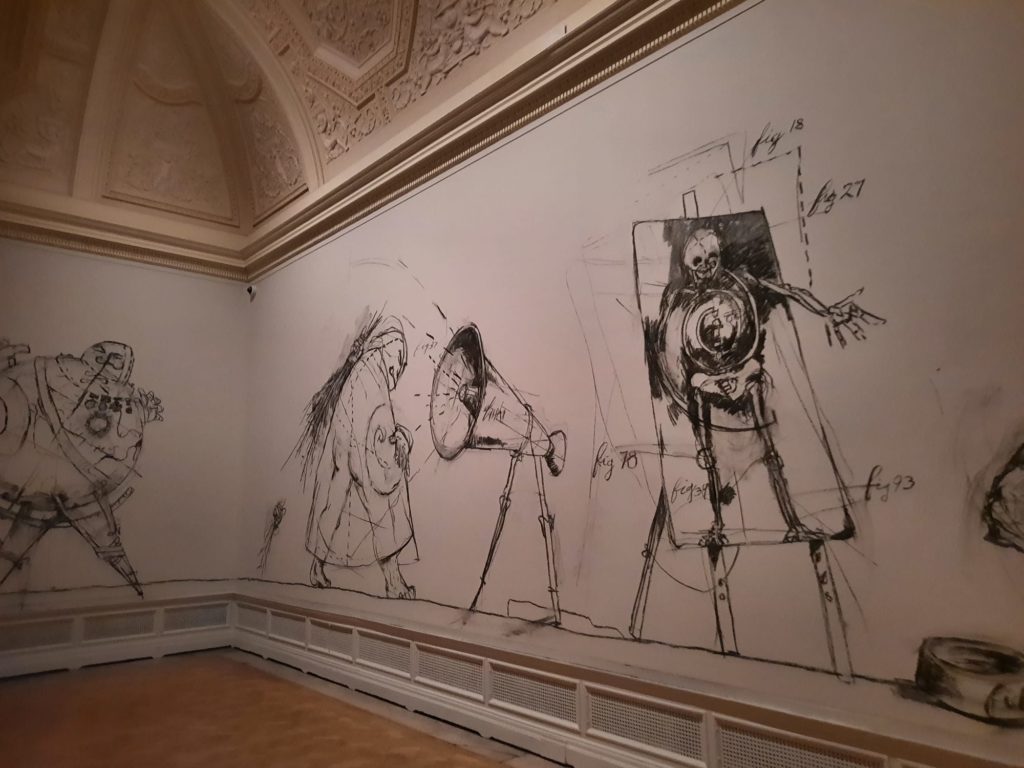

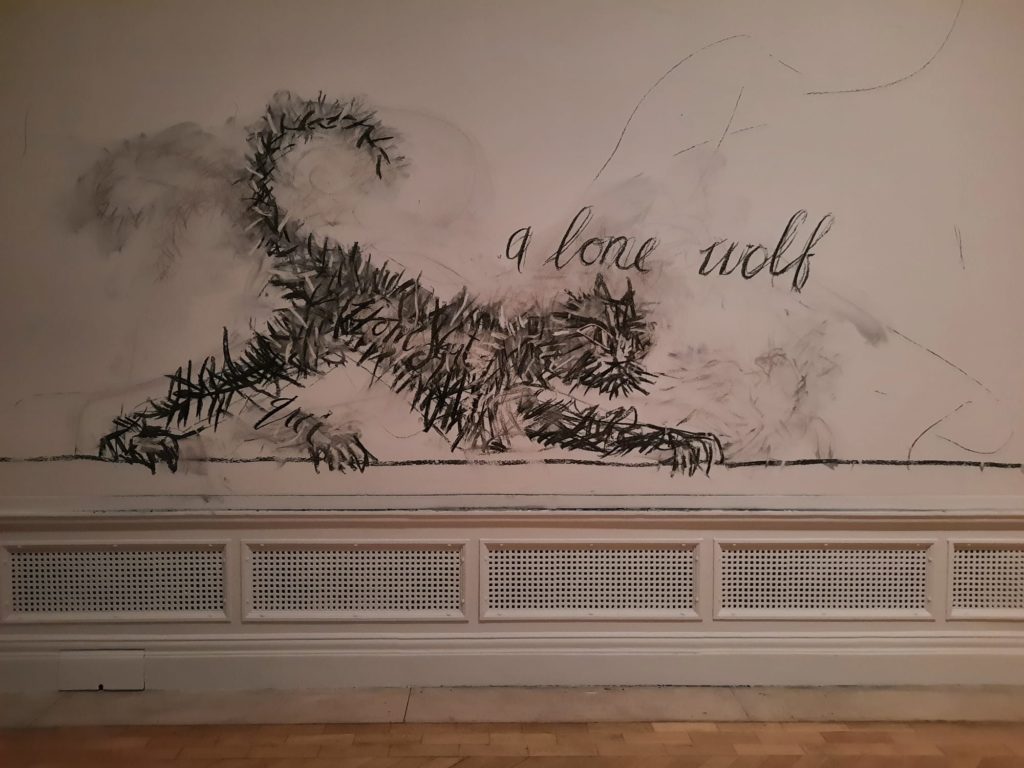

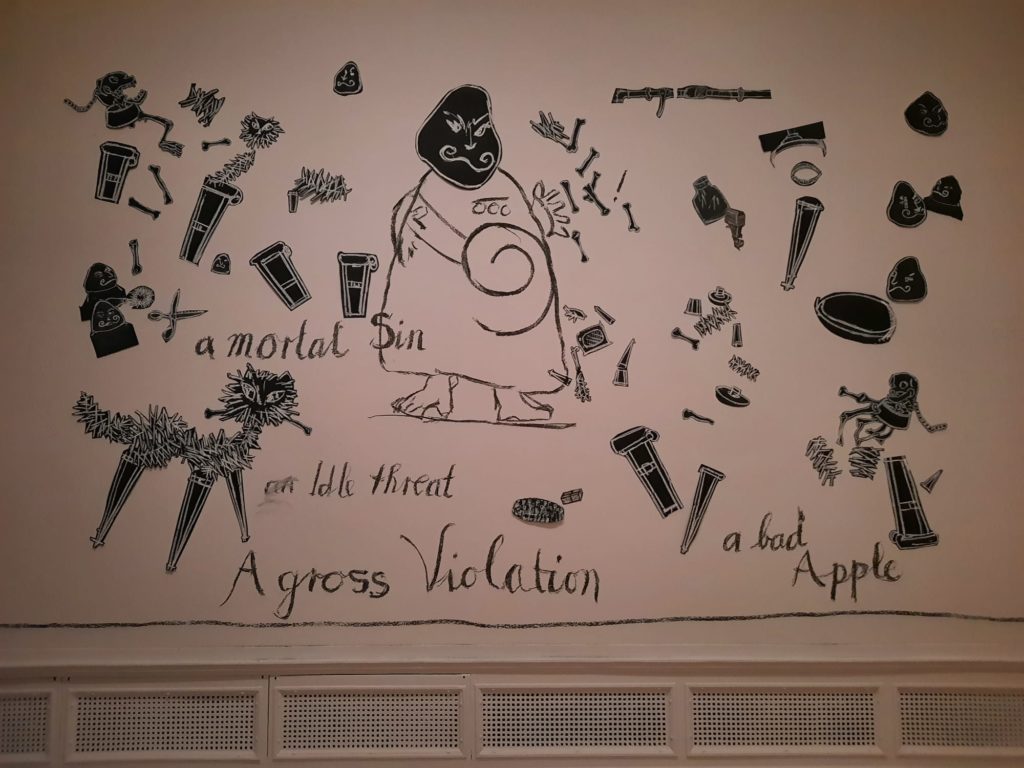

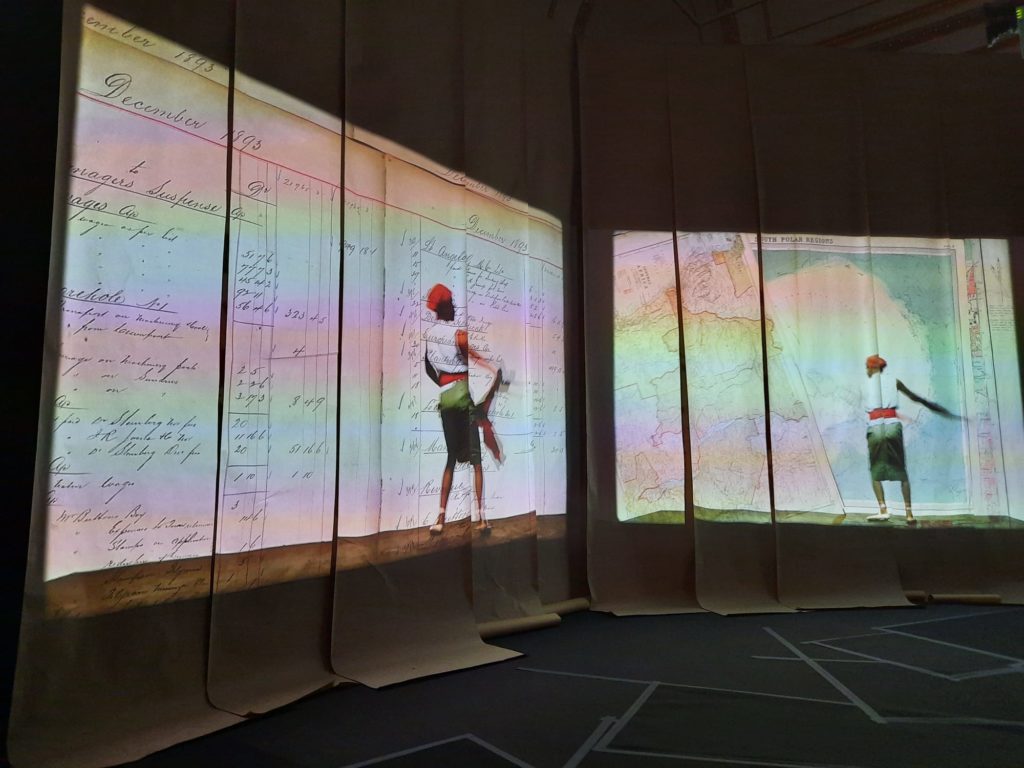

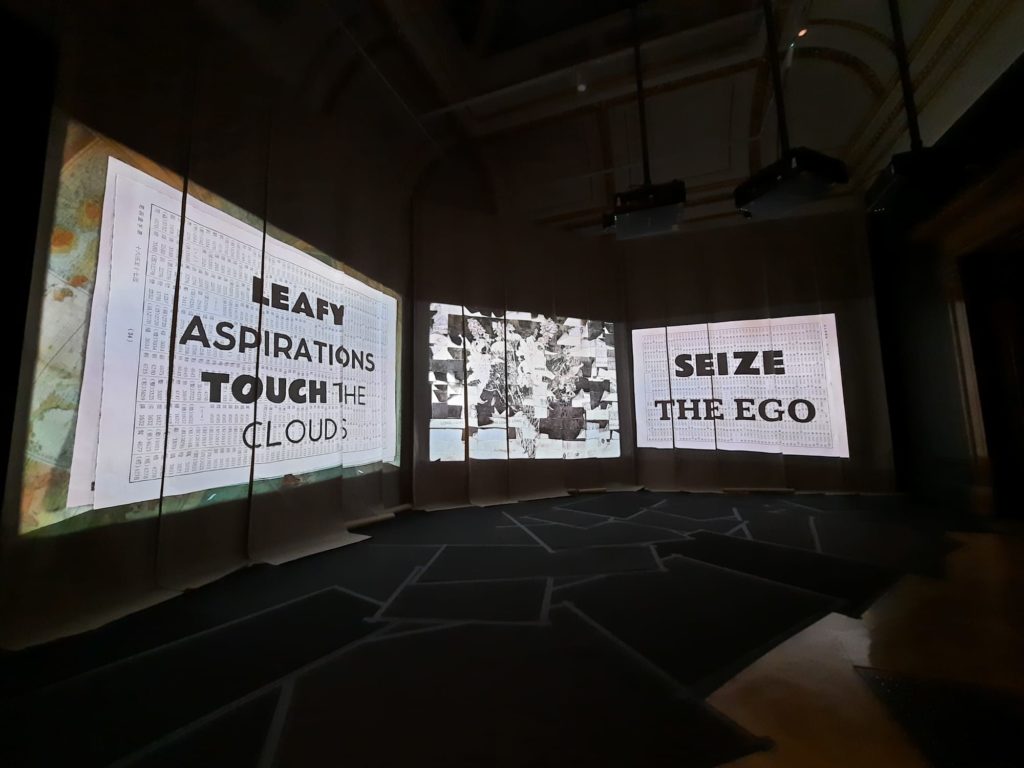

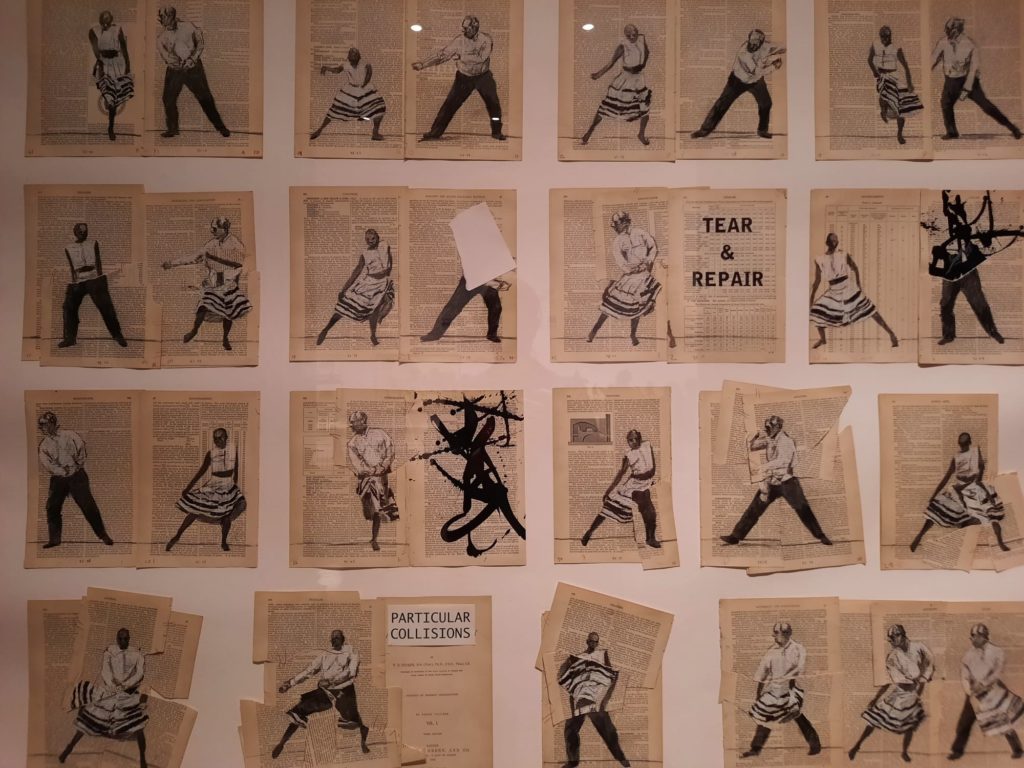

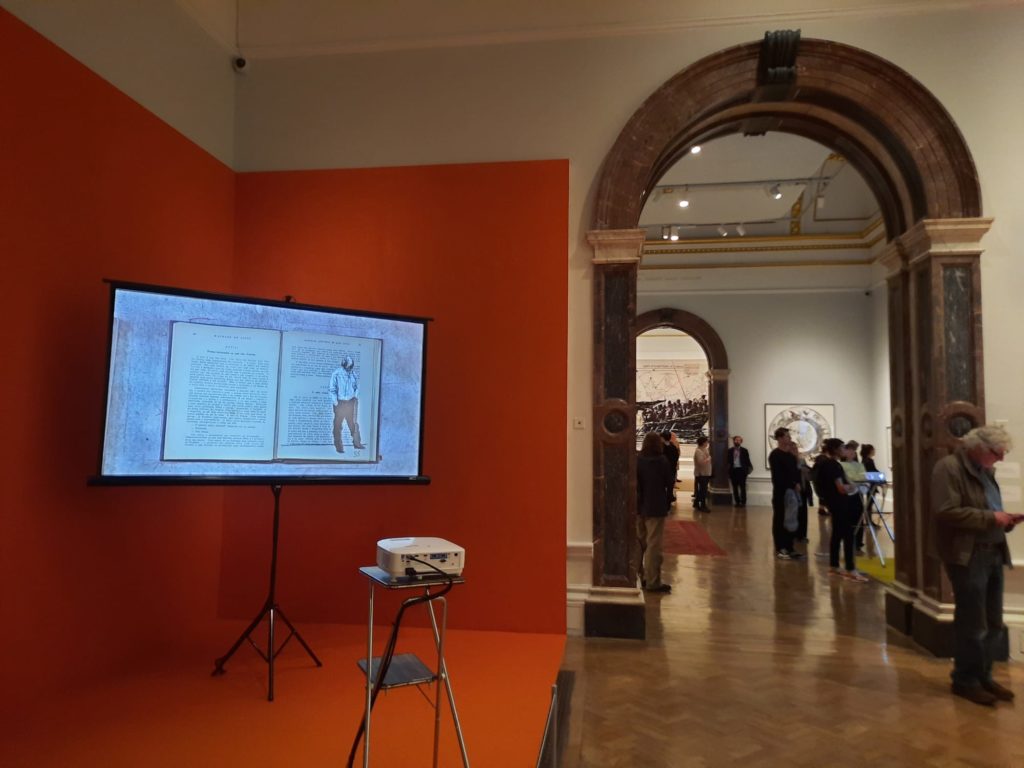

In terms of what is actually on view, it is quite varied. There are drawings, some of them the basis of the animations I spoke about earlier. Then there are the animations themselves, set up with little seating areas so you can take your time and watch them comfortably. There are tapestries, there are installations. There are costumes and props including from Sibyl. I even saw a couple of pictures for stereoscopes with viewers set up so you can see the images in 3D. And lastly there are a couple of site-specific drawings done directly on the gallery walls.

When I was preparing this blog post, I noticed that my images look quite monochromatic. Or rather are monochromatic, because most of them are photos of black and white prints or drawings in charcoal. But this isn’t the impression you get when you see the exhibition, which is more a sense of being an immersive world. Really I think what I’m saying is that you won’t get a full sense of this one unless you see it for yourself.

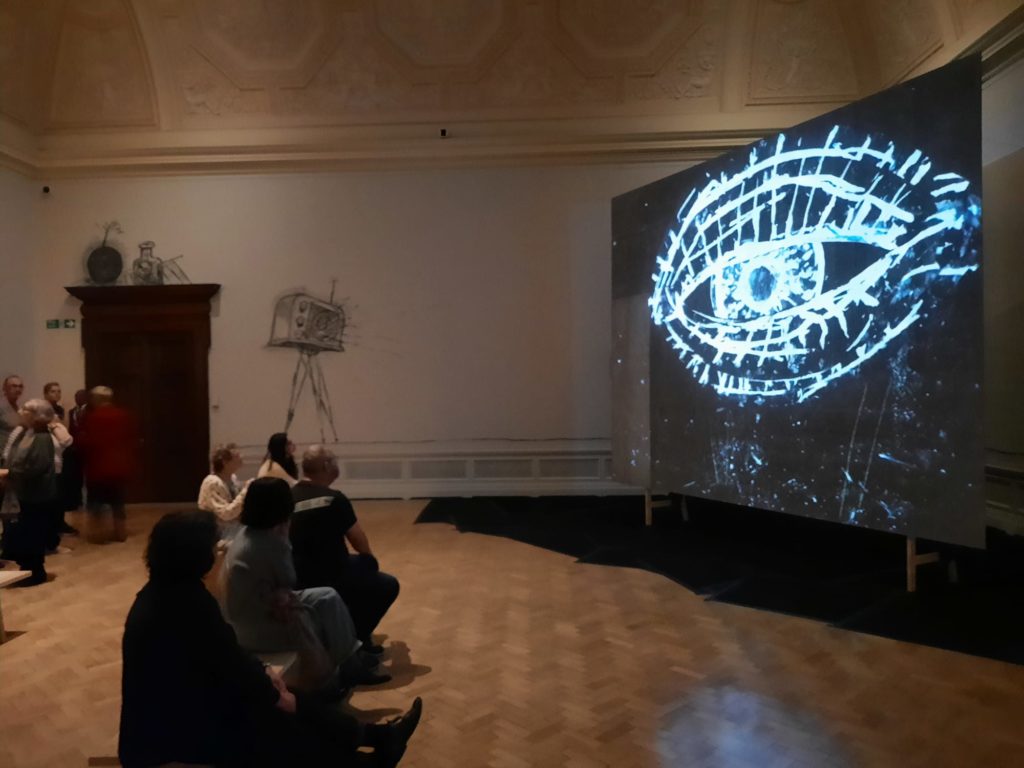

The Animations

When I saw Sibyl, I wasn’t familiar with Kentridge’s work so wasn’t expecting anything in particular. It was only by watching The Moment Has Gone that I slowly understood the technique. Which is to say, a series of drawings and erasures, filmed for a few seconds each time until an animation emerges. It somehow feels more like three-dimensional stop motion than a classic animation.

At the Royal Academy exhibition I was able to put this one work into a much richer context. Kentridge made a series of nine films starting in 2003, which together are known as Drawings for Projection. The most recent, City Deep, dates to 2020. An interesting feature of the films is that many contain Kentridge’s own image. Although it is not himself he is depicting. Instead, the films follow the story of Soho Eckstein. Eckstein is a property developer and mine owner, often weighed down in the films by various problems. It’s overtly political and specifically South African, with a strong Expressionist element.

The Drawings for Projection can all be viewed in one of the Royal Academy’s large galleries. I’m not always a fan of video art as I find the demands on my time galling, but you are quickly drawn into Kentridge’s animations by the analogue skill involved. A lot of fellow visitors seemed likewise enthralled, and this was generally a room which you want to set aside some time for. Don’t forget to check out the drawings themselves in a prior room, depicting of course the end state of the animation.

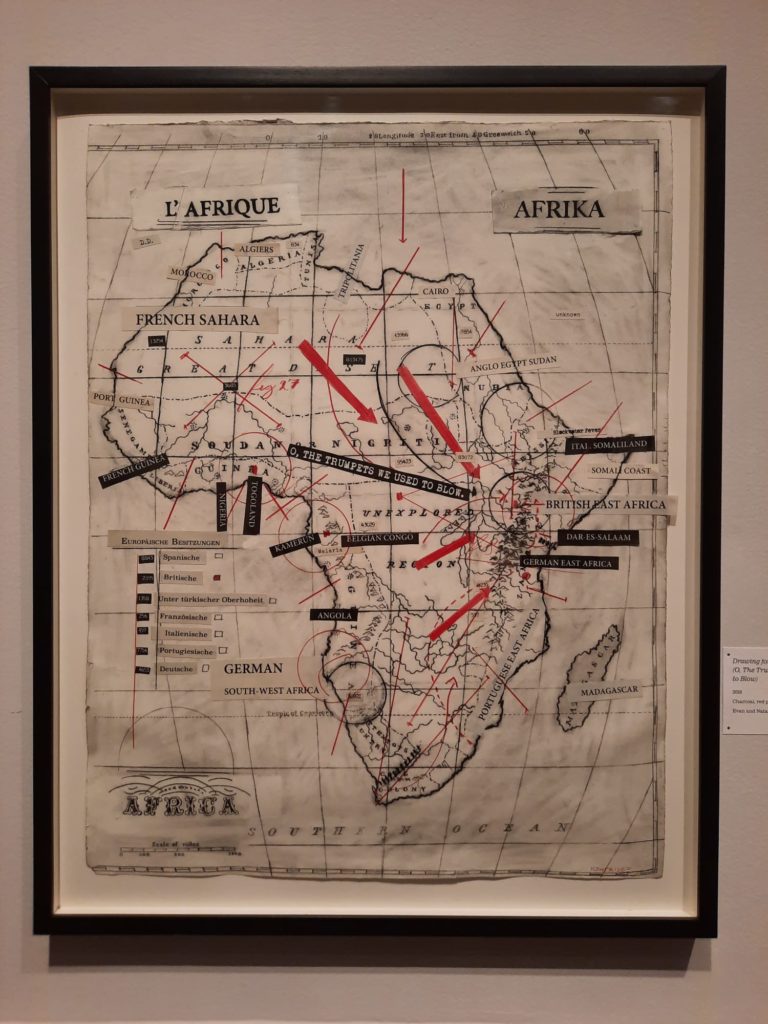

The Landscapes

Another series I particularly enjoyed in William Kentridge was entitled Landscapes. The premise relates to the process of 19th Century exploration in Africa, and its deeper meanings. We have probably all seen old engravings from expeditions by famous explorers like Richard Burton (not that one) or David Livingstone. Big waterfalls, noble viewpoints and all that. At about the time that these images were published, Africa was ‘divided’ between colonial powers at the Berlin Conference of 1884-5.

What Kentridge does is make visible the belief in cultural superiority underlying both the exploration and the conquest. His images of waterfalls and the like are no longer ‘unspoilt’ or unpeopled landscapes, but contain marks and lines which suggest the process of surveying and mapping. Which, to be fair, was probably the process going on in the minds of some of the explorers: arriving somewhere new and assessing it in terms of resources, boundaries and control. Other works in the same gallery reflect on the history of the hundreds of thousands of conscripted Black Africans who supported European war efforts.

What I liked so much about these series was the subversion of assumed neutrality. A map, after all, seems at face value like quite a neutral thing. It’s just noting down what is there, making sense of the world, isn’t it? Only it’s not. For all those Enlightenment values, making sense of the world is a biased and complex process. Value judgements are part of it, as are personal, political, cultural and religious interests. Kentridge surfaces these many-layered processes in a subtle, persistent and yet also aesthetically pleasing way.

Final Thoughts On William Kentridge

I saw this exhibition on a Sunday afternoon, and would suggest that it’s the perfect activity for such a time of leisure and reflection. Despite the fact that you’re making your way through the entirety of the first floor galleries, the works are often large so it’s not an overwhelming ask. You need to have time to fully take in each work or series, however. I went alone, and could have done with a buddy to talk through my reactions with.

I am really growing to like Kentridge’s work. It’s not easy, political and raw as it can be. But it’s very clever and the type of thing that you can see again and again, taking away something different each time. His Wikipedia page talks about how he initially wanted to embark on a career in theatre, but didn’t feel he had the talent for it. Theatre’s loss is clearly the art world’s gain.

Seeing such a big retrospective of work by a contemporary artist, and particularly a South African one, is a relatively rare thing in London’s museums and galleries. Don’t miss this opportunity to get under the skin of William Kentridge’s work, or let it get under yours.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.