Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, Dunedin

A visit back to my home town is a good chance to revisit and reappraise the museums I grew up with, including Toitū Otago Settlers Museum.

A Visit Home

In late 2022 I was finally able to take a trip back home, much delayed by the pandemic. Living in London, the city of Dunedin in New Zealand is almost exactly the opposite side of the world. The Antipodes. So with travel restrictions and so many connecting flights, travelling back here hasn’t been possible until now.

Since my last visit home I have relaunched the Salterton Arts Review with renewed vigour. So this seemed like a good opportunity to revisit some of the places I was once very familiar with, and reconsider them with a fresh perspective. As the main centre of the Otago region and a university city, Dunedin has a fairly vibrant cultural scene. There are a couple of museums, an art gallery that in the past has toured major international exhibitions including from the Guggenheim and Tate, and quirky smaller collections and galleries. While there’s no longer a professional theatre in the city, there’s a fair bit going on at the university, major touring artists over at the stadium, and even a Dunedin Sound in music (some time ago, but hey).

All in all not bad for a city of around 130,000 inhabitants. You can almost see how this would be a good place for a young arts and culture enthusiast to grow up, dreaming of a bright future blogging to her heart’s content! Coming into a new museum fresh and with a museological perspective is one thing, however, but I was intrigued to see how it would feel to come back to places I know well (or even briefly worked at) and considering them in the same way as I do institutions in London or abroad. First under the microscope is Toitū Otago Settlers Museum: read on to find out how I did.

Toitū Otago Settlers Museum

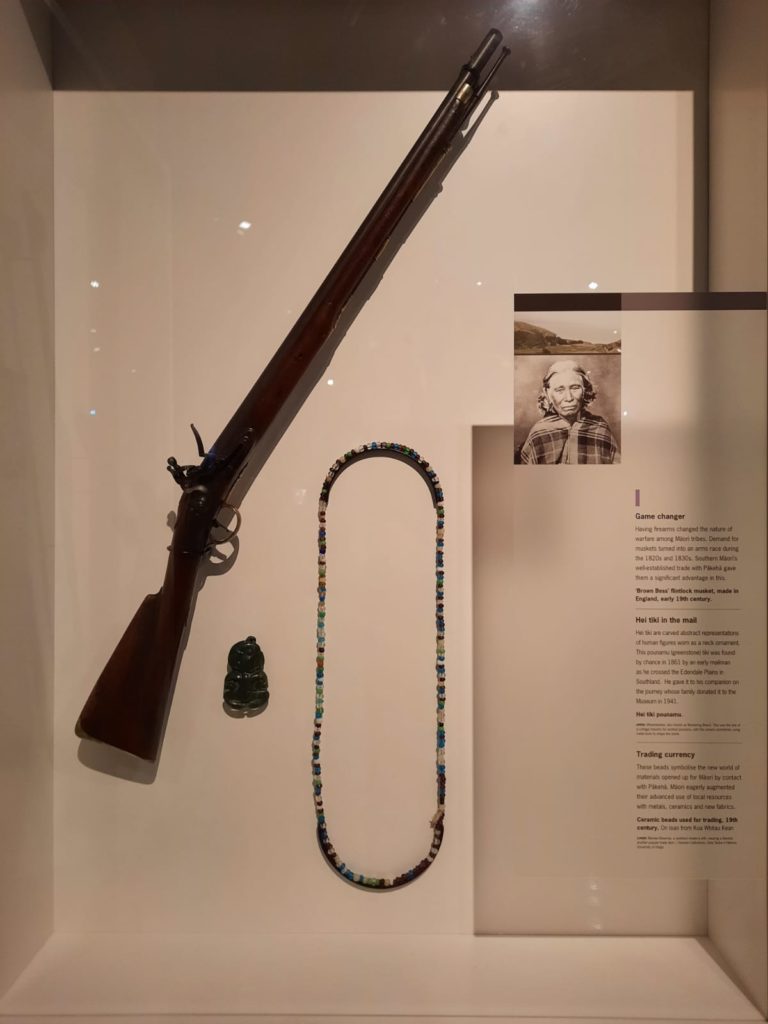

In a way, Toitū Otago Settlers Museum tells the story of changing attitudes towards the history of New Zealand. It is New Zealand’s oldest history museum, founded in 1898 by the Otago Early Settlers’ Association. 1898 was the 50th anniversary of the founding of Dunedin by Scottish settlers. The settlement of the region predated Dunedin, however, with Māori people living here from approximately the late 13th Century. Established settlements at Ōtepoti and Puketai were abandoned by 1826, due to a cluster of factors common to colonial contact and settlement: epidemics, conflict and economic pressures.

The Otago Early Settlers’ Association wasn’t about that kind of settlement, however. It was about documenting and preserving the experiences of colonial families. By 1908 it had premises in Dunedin and opened to the public. The focus in the early days was narrow: the history of settlement in Dunedin between 1848 and the first gold rush in 1861. Over the decades the museum has moved with the times, however. First the story expanded to include later settlers (this is when the museum dropped the word ‘Early’ from its name). It has experienced periods of decline and neglect, and also periods of growth and expansion. Often this aligned with the ebbing and flowing interest of New Zealanders in their own history.

The current phase of development could be said to have started in 2006. In this year work started to upgrade the facilities and combine exhibition and storage into a single site. In 2008 the museum gained its own directorship once more (having shared one with the Dunedin Public Art Gallery since 1995). After renovations starting in 2011, it reopened in 2012 with a new name, Toitū Otago Settlers Museum. Toitū comes from a stream which formerly ran close to the museum site, and means ‘to remain unchanged’ in Māori. This broader vision of fundamentally connecting to a place and telling its story over time shows how far expectations of a history museum have shifted. ‘Unchanged’ and yet very much changed at the same time.

Stories From Local History

A further disclaimer: as well as coming to [Toitū] Otago Settlers Museum since I was a little nipper, I also worked here for a time. When I was finishing off a Masters programme in Museology and before I moved to London, I did a combination of gaining volunteer experience and working as a gallery host both here and at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. At Toitū Otago Settlers Museum I volunteered for a day a week assisting the conservator, which was a fascinating experience. I got behind the scenes, saw a lot of the collection, and remember shifting things out of what is now exhibition space but was then storage, in preparation for the renovations I mentioned earlier.

But it was spending time as a gallery host that meant I learned the content of the exhibits inside out. That was more than a decade ago now, but the bones of the current permanent exhibition are the same. Toitū, like many history museums, is broadly chronological with thematic deep-dives into certain topics. The displays are object-led, with explanatory texts. Some objects are ‘old favourites’ so are still on display, while others had changed since the last time I came. I also recognised some of the multi-media exhibits which require more investment and therefore have a longer lifecycle – like a recreated ship’s cabin with videos to watch about life on board.

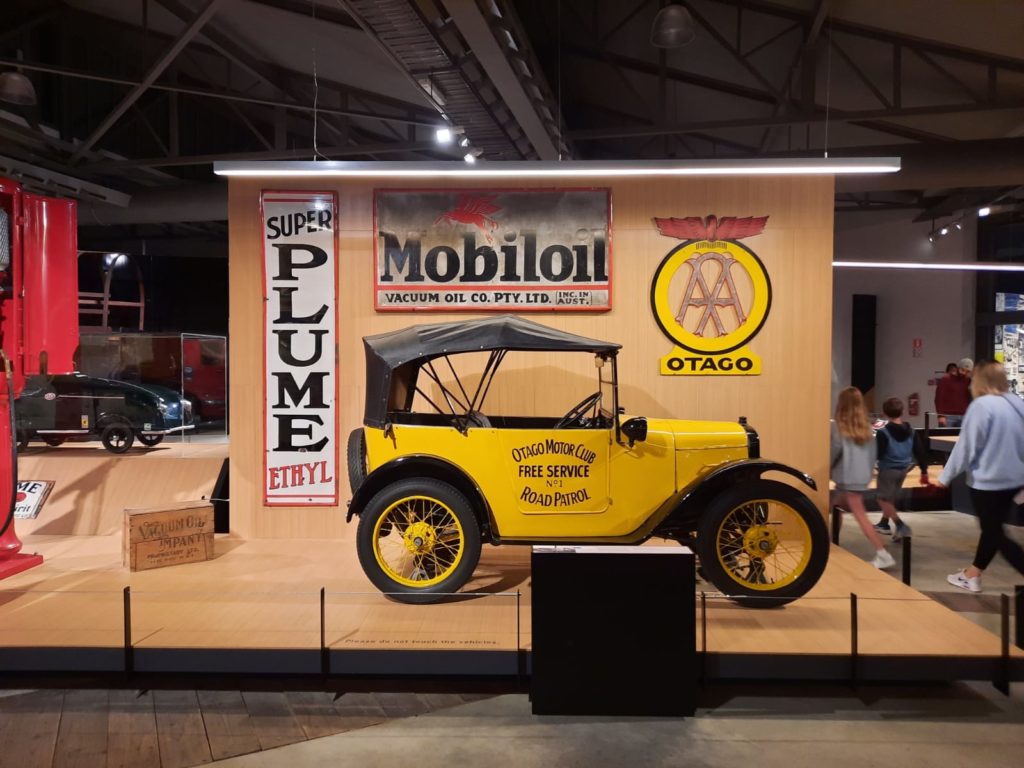

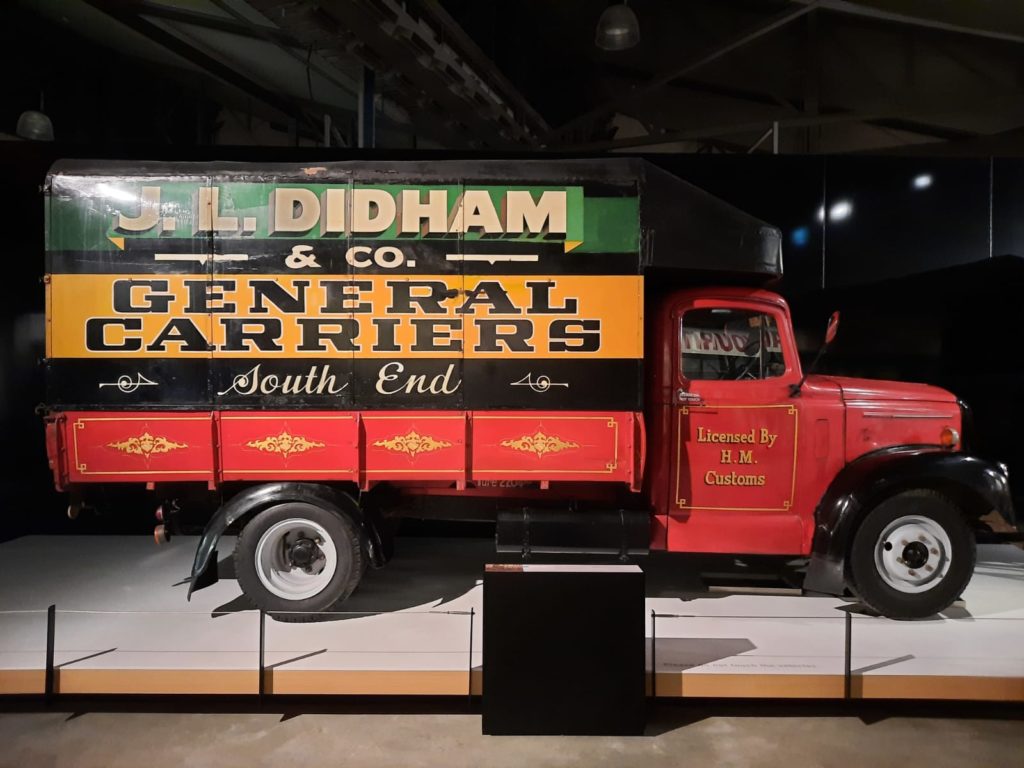

The museum floor space covers a couple of city blocks, so is actually fairly immense. The history covered ranges from initial Māori settlement and first contact, to Dunedin’s expansion during the gold rush in Central Otago, later social history, specific waves of immigration, and more. There is a large section on transport, and another on technological development. There are even nods to the history of the museum: the Smith Gallery, hung with portraits of those early colonial settlers, has been a feature since its opening in 1908. I remember it well from my own childhood, and even have a relative or two somewhere on the walls.

Stories About Ourselves

So with so much to take in in Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, what is this museum really all about? In my opinion, it is a museum which sets out to tell visitors about themselves. Of course there are out of town visitors and tourists who come here. But primarily it feels like this is a museum focused on its importance as a memory store for the community. Let me tell you a story to illustrate what I mean.

When I was a child, there was a department store in Dunedin’s central square, The Octagon, called D.I.C. (the Drapery and General Importing Company of New Zealand Ltd). By the 1980s it was bought out by another now defunct department store, Arthur Barnett’s. The key point to this story is about Christmas. Because the D.I.C and Arthur Barnett’s were where a lot of local families took the kids to have photos taken with Santa. To entertain them while they were in the queue, they could peer through windows at scenes from Pixie Town, mechanical models built by Nelson man Fred Jones from the 1930s and sold to the D.I.C. in the 1950s.

Since 2004 Toitū, now the Pixie Town models’ guardians, have brought them out almost annually in a new local tradition. First parents and grandparents brought their children here to show them something they remembered seeing in situ. Now we must almost be getting to the point where parents can bring their children to see something they remember seeing here at Toitū when they were young. An experience meaningful to local people has been transposed and memorialised within the museum context, taking on new stories and meanings in the process.

Visiting Toitū

I’m going to go right ahead and assume that if you’re a local, you know all about Toitū already. For visitors, Toitū is a good option with kids as there are plenty of interactive exhibits. Or for those with an interest in social history. As it’s so big, and also free, you may want to split your visit into installments. The museum is split down the middle into broadly 19th and 20th Century sections (transport in the latter half) so lends itself to this.

With the perspective of a few years behind me, Toitū is still an enjoyable and educational place to visit. The changes that I’ve seen since my time there have continued the journey to shifting the focus from the colonial settlement of the city and region. There’s more than ever before about different communities, perspectives and ways of life. That isn’t to say the journey is complete because it’s not, but I appreciate the changes I’ve seen.

To go back to the idea of Toitū as something unchanging, I would like to reflect briefly on the different levels this works on. The museum, as I’ve just finished saying, has changed a lot. Dunedin has also changed substantially since the days of the Otago Early Settlers Museum. But the place that we call home, the landscapes, the essence of it – maybe that is the unchanging constant underneath it all. Or perhaps its the urge to record our histories, to give them the appearance of permanence that museums so handily provide.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

2 thoughts on “Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, Dunedin”