Národní Galerie Praha – Klášter sv. Anežky České (National Gallery Prague – Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia)

The National Gallery Prague houses its medieval art in the historic Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia. A marvellous place to display religious items with a connection to their original settings.

How To Choose A Museum In Prague

I recently had an opportunity to travel to Prague, with a couple of hours to myself to do with as I pleased. The last time I was here, I was exploring during the early mornings and went on this walk. Since my timing was a bit more sociable on this occasion, I decided on one or two museums instead.

Prague is a wonderful city for museums. It’s also a wonderful city for tourists so some of them are of dubious educational value, but that’s also just me being a bit of a museum snob. As well as Prague Castle, there are museums of/about art and history (communism, national museum etc.). There are museums devoted to prominent citizens in different fields, for example Franz Kafka, Alphonse Mucha and Antonín Dvořák. You can dive into technology or agriculture, Jewish history or literature. You would need weeks, if not months, to see it all.

I’ve been to Prague as a tourist a couple of times in the past, so have seen several of the main draws. I was hoping to go a little further off the beaten track this time, as well as ideally a couple of things close together so I could pack them into my free afternoon. In the end what I selected was one of the branches of the Národní galerie Praha (National Gallery Prague) plus one of the museums flirting with the tourist end of the spectrum, so after reading both you can be the judge of whether I achieved this aim.

A Museum In A Convent? What Is The Convent Of St. Agnes Of Bohemia, Anyway?

The first of these museums, the Národní galerie Praha – Klášter sv. Anežky České, translates as the National Gallery Prague – Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia. A museum in or about a cloister, therefore? Yes, it’s the former. This branch of the national museum is housed in a former cloister with an interesting history.

St. Agnes of Bohemia was the youngest daughter of a king, born in 1211. Raised in a convent, she was twice betrothed to kings and emperors but, given a chance to forge her own path after the engagements were broken, chose instead to found a convent of her own. Having a royal family’s support and resources undoubtedly helped in this aim, and the convent was spacious and also enjoyed papal support.

St. Agnes (who by the way only became a saint in 1989) founded a hospital and two friaries for Franciscan monks, on land donated by her brother, Wenceslaus I of Bohemia. Through the friars she learned of the relatively new order of Poor Clares, founded by St. Clare of Assisi. The Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia thus housed both men and women, although the Poor Clares live in seclusion so there was of course no contact between the two.

I wrongly assumed before reading further about it that the convent no longer being a convent might be to do with the communist period. But the decline of the Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia actually started many centuries earlier. After Agnes’s death, in fact. She had trained up a relative, Kunigunde of Bohemia, to take over. But Kunigunde got married off, the focus of royal religious activities moved elsewhere, and the convent went through a long decline with occasional highs as well as lows. It was an armoury and mint during the Hussite Wars, then a convent again, and was finally sold off in 1782 by Holy Roman Emperor Josef II who dissolved many churches and monasteries. It became flats, workshops and storage, enjoyed renewed interest and some restoration in the early 20th Century, and became part of the National Gallery in 1963.

A Fitting Display

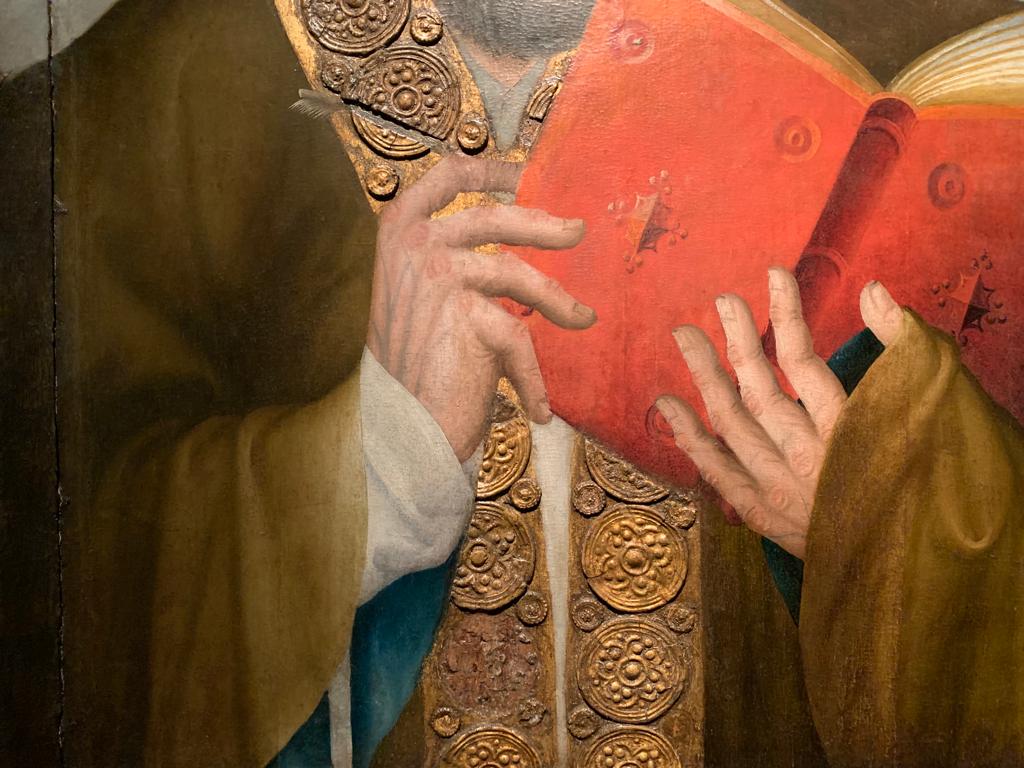

Originally, the National Gallery had 19th and 20th Century Bohemian art on display here. At some stage they decided to display medieval art instead. This choice seems better both in terms of the period and the subject matter. Medieval art of course, unless you’re talking folk/applied art, is basically all religious. And so it is that the Cloister of St. Agnes is filled with innumerable religious scenes. Mary with the infant Jesus. The Last Supper. The Crucifixion, the Descent from the Cross and the Resurrection. The lives of the saints. Various saints and donors. If you’re at all familiar with art history, you can picture the scene.

You enter the gallery on the first floor. There is a one-way path set up for about half of it, which makes it easy to navigate. With so many museums to choose from in Prague and this one being a little tucked away and of specialised interest, it’s quiet. For a while I thought I was the only person there. If you need a break from looking at so many devotional images, the windows look out over the cloister. The experience is a peaceful one. It’s also a more extensive one than I had anticipated. Since I only read up about the cloister after the fact, I was expecting something much smaller. In the end I had to move at a reasonable pace in order to see everything before my next museum tour was booked.

Medieval Exchange Of Ideas

A very clear thread in this branch of the National Gallery was the exchange of ideas throughout Europe in the medieval period. The art on display is mostly, but not exclusively, Bohemian. Other artworks are French, Austrian and Saxon in origin, for instance. Prague was an important centre throughout the medieval period. It attracted artists and citizens from different places, and was the site of a robust exchange of ideas.

As you wander the rooms you can see artworks with influences including Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance. The works tend to be in groupings by subject matter and style. Information panels are simple, but always include the original location of the work (ie. the church it came from) where known. It doesn’t take long, therefore, to build up a mental library of motifs and developing styles, and make connections between works.

If you really want to get into detail, there is an NGP (National Gallery Prague) app specifically for this purpose. You can find it by following these links to the App Store or Google Play. It takes a handful of works and delves into important details, drawing your eye to things you might otherwise miss. There are even fun but slightly infuriating puzzles where you have to try to put paintings back together. If I had longer I would have liked to take my time with this app during my visit. With so many similar works, it’s a good way to break things down into manageable chunks.

What Lies Beneath The Surface

When I visited the Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia the temporary exhibition (now ended) was In Depth and on the Surface. The exhibition was integrated into the permanent collection, and focused on restoration and scientific analysis of the collection. Information is spread across several large text panels, and looks in depth at learnings from analysing specific artworks. Techniques include x-ray to tomography, and tell us more about the materials used, old repairs, and details now missing.

It’s clear that this exhibition relates to a careful programme of research and restoration more broadly. There are over 200 works on display in this branch of the National Gallery Prague, and works of this age normally present significant conservation challenges. I could see evidence of where woodworm, cracked panels and flaking paint have required stabilisation. The works are not restored to original condition, but show their age while also telling us how they were originally used.

For me this is the key overall to this museum. To our modern eyes these are artworks. Yet they were created in a context in which individual authorship was not important, religious intent was. These are devotional works, from specific contexts mostly within Bohemia. The National Gallery do a better job than most museums at walking the line between these two identities: art and worship. Scholarship and preservation are part of helping to paint this picture.

Don’t Forget To Explore The Convent Of St. Agnes Of Bohemia

But not like I did. As I said above, through most of the gallery you follow a one-way path. Pretty much as soon as there was an opportunity to go in the wrong direction, however, I did. At one stage I had an opportunity to either go around another side of the cloister, or down into a large room. I chose the latter. Then I had an option of either seeing the rest of this large room, or going down some stairs leading towards the churches. Again I chose the latter. Only, when I had finished my church interlude, I realised I had gone through a one-way door and couldn’t get back.

No problem. I made my way back to the start. When the lady scanned my ticket and it came up as already used, I tried to explain. Realising we didn’t have a language in common, I used Google Translate to tell her what had happened. She didn’t use Google Translate back, but I’m pretty sure what she said is that it was not her problem, I should buy a new ticket, but I was clearly an idiot she was going to take pity on and let back in. She wasn’t wrong, and we got there in the end.

So my advice is to go right around the cloister first, and then double back towards the big room. Only after that should you head down to the churches. They are impressive spaces befitting their royal origins. Look out for the engraved tombstone of Queen Kunigunda of Hungary. There’s also a lapidarium, and various rooms that fulfilled different purposes in convent life. It’s a nice way to finish, and reflect on the original settings of all this religious art.

The National Gallery Prague – Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia is far enough off the beaten track to be an interesting choice while in Prague. Yes, even though it is part of the National Gallery. It’s an interesting slice of Prague and Bohemian history. Plus a great example of the contextual display of medieval religious art.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

Could this be the world’s biggest collection of ‘Marys’? I do appreciate a woman being the star of the show and it looks like a lovely location. I like art from this period – good enough to look convincing but weird enough to be entertaining; Jesus looking dubious about having his arm fondled and the sexy pose headstone… among others! These pieces lend themselves to funny captions….and respect for the craftspersonship.

I find it very relaxing – all these nice peaceful figures (apart from all the martyrdoms of course), you know what it’s all about, and you can’t possibly retain all the information about which church they came from and which Master of the Life of Saint Someone created them, so you can just wander around and enjoy. And yes, possibly one of the biggest collections of religious art I’ve seen! There was a Jesus statue with an original horsehair wig which was one of my favourites, I never thought of the statues having wigs before!