TOSKA – Sort Sol / The Hope Theatre, London

Toska uses movement to tell the story of three Russian sisters who murdered their father. A powerful and politically engaged piece of theatre.

Content warning: mentions of death and abuse.

The Story Of The Khachaturyan Sisters

It’s a story so shocking it barely feels real. And yet we know it is a story that plays out every day, in various ways, all around the world. This is a very Russian version. In 2018, after years of physical, psychological and sexual abuse at his hands, the three Khachaturyan sisters (then aged 17, 18 and 19) killed their father. Mikhail Khachaturyan had isolated and tortured his daughters until they felt no outside help was possible. After one final incident involving pepper spray, they stabbed and beat him to death. A terrible end to a terrible tale.

Only, predictably, this was not the end. In fact, the sisters still await trial. The psychological impacts of abuse on victims who kill their abusers is still poorly understood and difficult to properly establish in a legal or trial context (see this example closer to home). Even more so in Russia where, since 2017, domestic violence not resulting in hospitalisation has been legalised.

The Khachaturyan case captured the imagination of the Russian public. They have received much support, with calls to fully take their father’s abuse into account as extenuating circumstances. His crimes are now documented. But it is difficult to ascertain what progress, if any, has been made in the last few years. The sisters face a potential sentence of eight to twenty years, but have already been waiting for five years and counting. The culture of nationalism and patriarchy in Russia means there is also public resistance to any leniency.

Toska

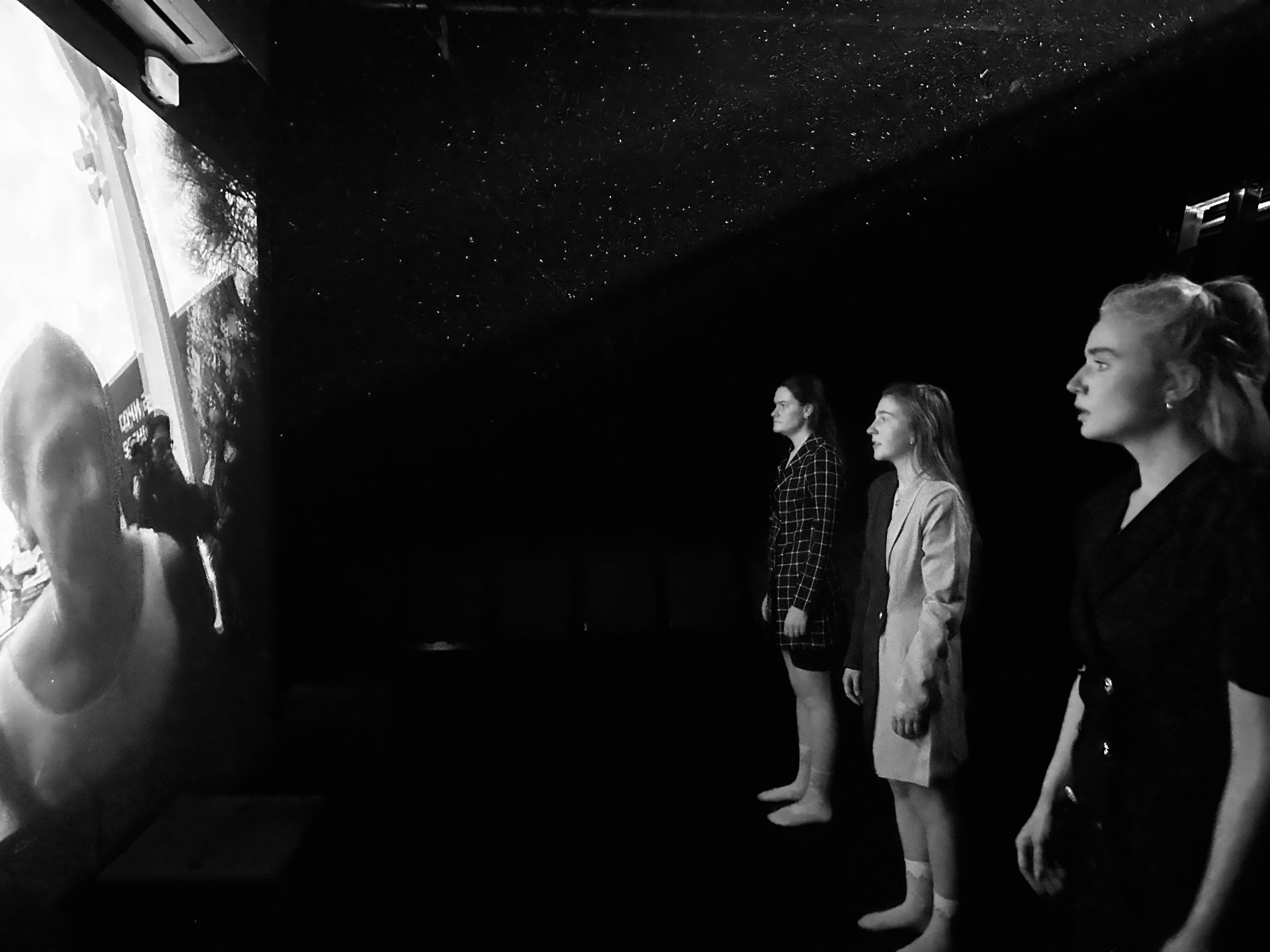

This sad story is the subject of Toska, a work by Elizabeth Huskisson for Liverpool-based theatre company Sort Sol. After appearing at the Durham Fringe and Bridge House Theatre in Penge, Toska has transferred to the Hope Theatre in Islington. In the work, Huskisson tells the sisters’ story mostly through movement. Three actors represent the sisters, and tell the story in three parts: what came before, the murder, and the aftermath. There have been some cast changes compared with earlier versions. Phoebe Mercer and Alfreya Bell reprise their roles, while Huskisson takes on the role of eldest sister Krestina herself.

Knowing relatively little about the Khachaturyan sisters before seeing Toska (I’ve been reading up since), for me the choice of medium was a very interesting one with both pros and cons. Dance and movement can connect with us more directly than other forms of theatre. In a story with so much suffering, there were moments where I felt it in a way that a more narrative piece of theatre might not have been able to achieve. Toska consists generally of sequences of movement, which often degrade or break down. The set is bare with the exception of a couple of boxes and a few props, so the focus is almost exclusively on the actors. Their commitment is superb, as is their ability to transmit emotion through subtle changes in each sequence. Alfreya Bell in particular plays youngest sister Maria with a tremulous, glass-like fragility.

At the same time, there were moments where I felt the formality of Toska created a distance between myself as a viewer and the story. The sequences of movement sometimes felt one or two repetitions too long. The costumes are also stylised: variations on a babydoll dress to represent childhood and lost innocence, for instance. And where language is used, it tends to either be formal, or occasionally in Russian without translation. So there was a tension for me between pulling me into the sisters’ psyches with one hand, and pushing me away a little with the other.

Final Thoughts On Toska

Having said that, I admire Huskisson and Sort Sol’s commitment to bold storytelling. Would a media headline or even a more traditional play on the same subject have stuck in my brain in quite the same way? I’m not sure. With such a source, particularly where the outcome is not yet known, a classic narrative falls short. What we have instead is an attempt to connect with us at a human level, across distance and differences in culture and experience.

It’s also a case study for politically-engaged theatre and social activism. Toska makes its stance very clear, both in its dialogue and with footage from Russian news and demonstrations (including what looks like Pussy Riot). Visual design by Lewis Dragisic and sound design by Louie Johnston-Ward complement the overall aspiration. It doesn’t need to be didactic: the average-theatre goer will know enough to set the scene, and Toska then fills in the details.

This is an experimental and powerful piece of theatre that will stick with you. Catch it at the Hope Theatre in Islington until 29 April. At only 45 minutes, there will be plenty of time to have a beer and discuss what you’ve seen downstairs.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Toska on at the Hope Theatre until 29 April 2023

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.