Trinity Buoy Wharf, London

A sunny winter’s day walk takes me to Trinity Buoy Wharf, an interesting case study in post-industrial mixed-use arts spaces.

Trinity Buoy Wharf

Just when you thought I was done with the Docklands after all those lockdown walks I did… Never fear, there is always something new to discover! On a recent outing in which the Urban Geographer and I joined an Open City walk around Canary Wharf, we finished at Poplar. I knew that there was a cultural location on my list that wasn’t too far away, and lo and behold discovered it was only a short walk to Trinity Buoy Wharf.

I knew very little about the place before going there. Just that there was some sort of long-term sound installation, and other artistic goings on. The great thing about Trinity Buoy Wharf is that you don’t need to know anything going into it. Walking from the East India Dock Basin past ghost signs (including one for a whale oil company), information panels explain the area’s former industries, geography, and social life. From a rural orchard (hence this approach being along Orchard Place), to a site of plate glass manufacture and whale processing, a site of poverty in the Victorian era and abandoned as an industrial area by the late 1980s. It’s like a story of the London Docklands in miniature. If you stop to read all the panels, you will arrive very well-informed indeed. And if you don’t? They are repeated within the Trinity Buoy Wharf complex itself.

And so I did arrive, on my wintery weekend afternoon walk. We stopped first to warm up and have some lunch at one of two on-site venues (there’s a cafe and a diner). And then sallied forth to explore. The site itself is relatively small, but has several different points of interest. Let’s read a little more about the history of the wharf itself before diving into its modern incarnation.

A Short History Of Trinity House

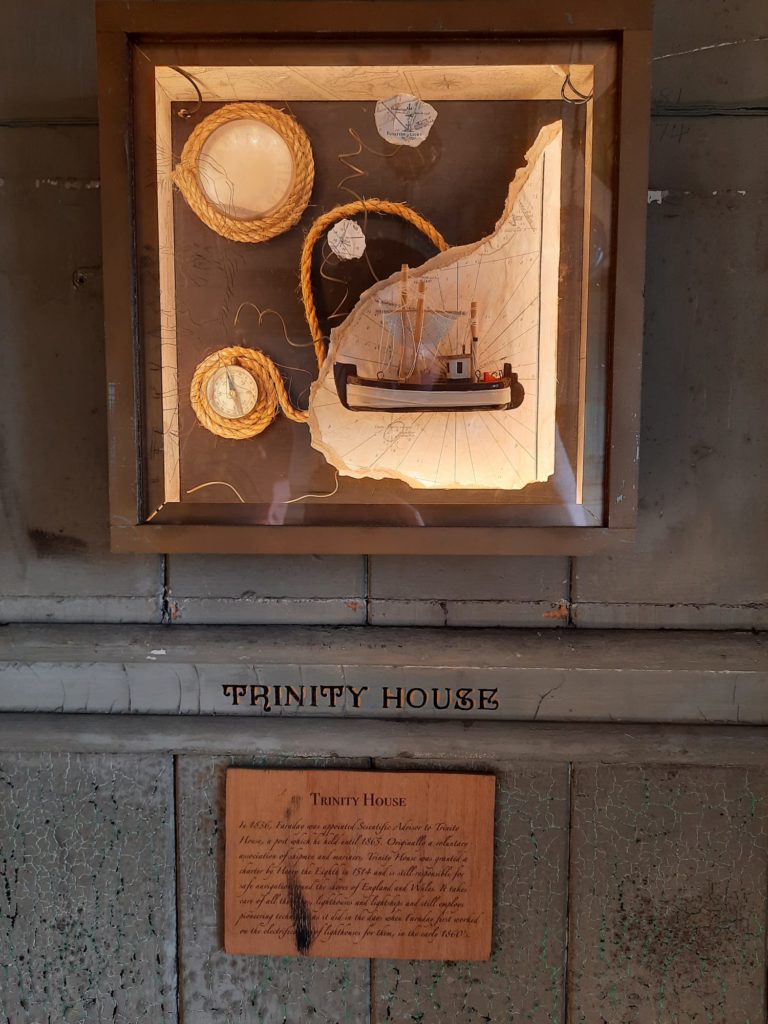

The most significant feature of Trinity Buoy Wharf remains its lighthouse. This lighthouse, however, is not quite what it seems. It all goes back to this wharf being a workshop for the Corporation of Trinity House of Deptford Strond, whose full name is the The Master, Wardens and Assistants of the Guild Fraternity or Brotherhood of the most glorious and undivided Trinity and of St Clement in the Parish of Deptford Strond in the County of Kent. Goodness. Want to hazard a guess at what this brotherhood is all about? Well, they remain the official authority for lighthouses in England, Wales, the Channel Islands and Gibraltar. Plus are responsible for other navigational aides such as buoys, lightvessels and maritime communication systems. And are also an official deep sea pilotage authority.

Trinity House, as the corporation is now generally known, was founded in 1514. 1803 is a more significant date for us, as this is when they established the Blackwall Depot as a buoy workshop. It was a good spot for maintenance and storage of the many buoys they needed along the Thames. Trinity House’s engineer, James Walker, built a first lighthouse here in 1852. It was demolished in the 1920s. A second, the one we see today, was built between 1864-66. This was an experimental rather than functional lighthouse, however. Electric lighting for lighthouses was a newfangled idea at the time, and the first lantern in this second lighthouse came from the Paris Exposition of 1867. Michael Faraday worked here carrying out experiments. It was also used to train new lighthouse keepers.

Trinity Buoy Wharf Today

By the late 1980s Trinity House no longer needed this space. They sold it to the London Docklands Development Corporation in 1988. The LDDC in turn leased it to Urban Space Holdings Ltd. in 1998 to develop as a ‘centre for the arts and cultural activities’. Today it’s a mix of studios and office space (in ‘container cities’) and exhibition space. The University of East London are based here, as are the Thames Clipper boats. There are historic boats permanently docked here, and even a prep school. A properly mixed-use space.

I was, of course, most interested in Trinity Buoy Wharf as a historic site and arts venue. Unfortunately, however, the site is so truly mixed-use I wasn’t able to see the main draw on the day I visited. The lighthouse is home to Longplayer, a thousand-year-long musical composition conceived and composed by Jem Finer. The idea is that it mirrors planetary systems, only coming into alignment again a thousand years after it began on 31 December 1999. When we visited, the lighthouse was closed due to a memorial service taking place in the adjacent building. I shall have to go back to see it, although there is also an option to livestream it (which I am in fact doing right now) or go to listening posts in Yorkshire or San Francisco.

Other than Longplayer and visiting the lighthouse, what else is there to see? We had a walk around looking at the exterior of the buildings and the modern shipping container architecture. There are some outdoor artworks and a tidal powered lunar clock. The historic boats are interesting, including a Thames lighter from circa 1890. A shipping container called the ‘Story Box’ has videos of the site’s history and depiction in film. And finally there’s a curious little installation called The Faraday Effect. Let’s take a look at that in detail now.

The Faraday Effect

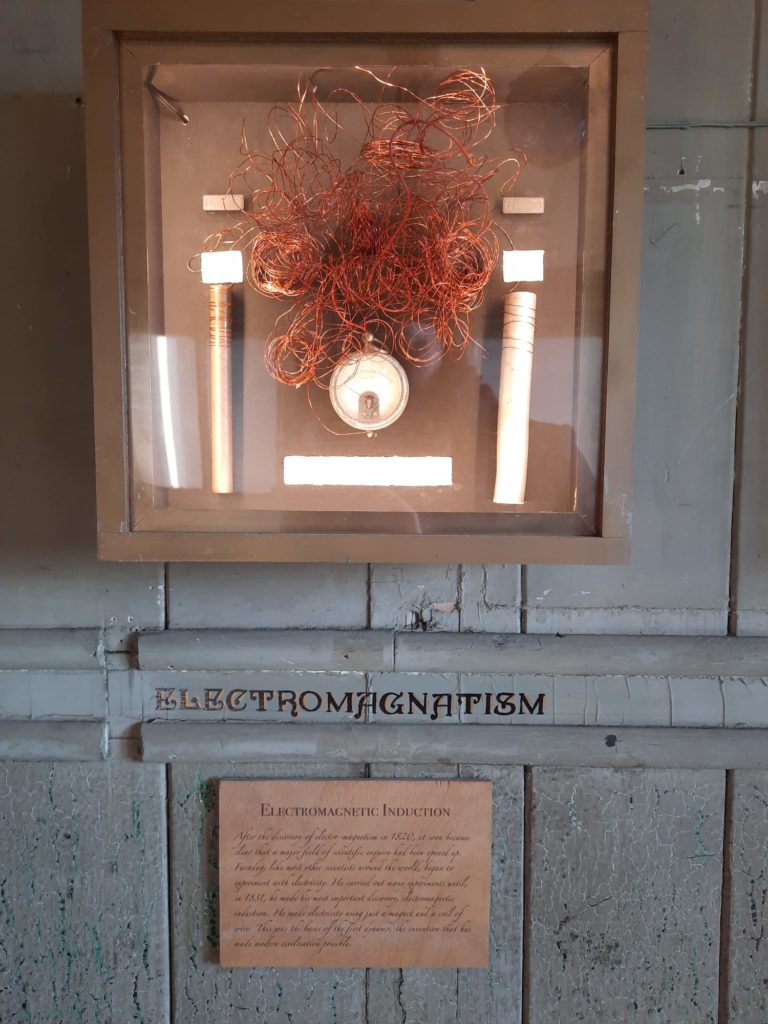

Michael Faraday became Scientific Advisor to Trinity House in 1836. He looked at the “security and constancy” of lights, their lenses, and their power source. He worked first on improving combustion-based lighthouses to ensure cleaner burns and therefore more light to guide ships, but also conducted experiments in electricity and magnetism from Trinity Buoy Wharf.

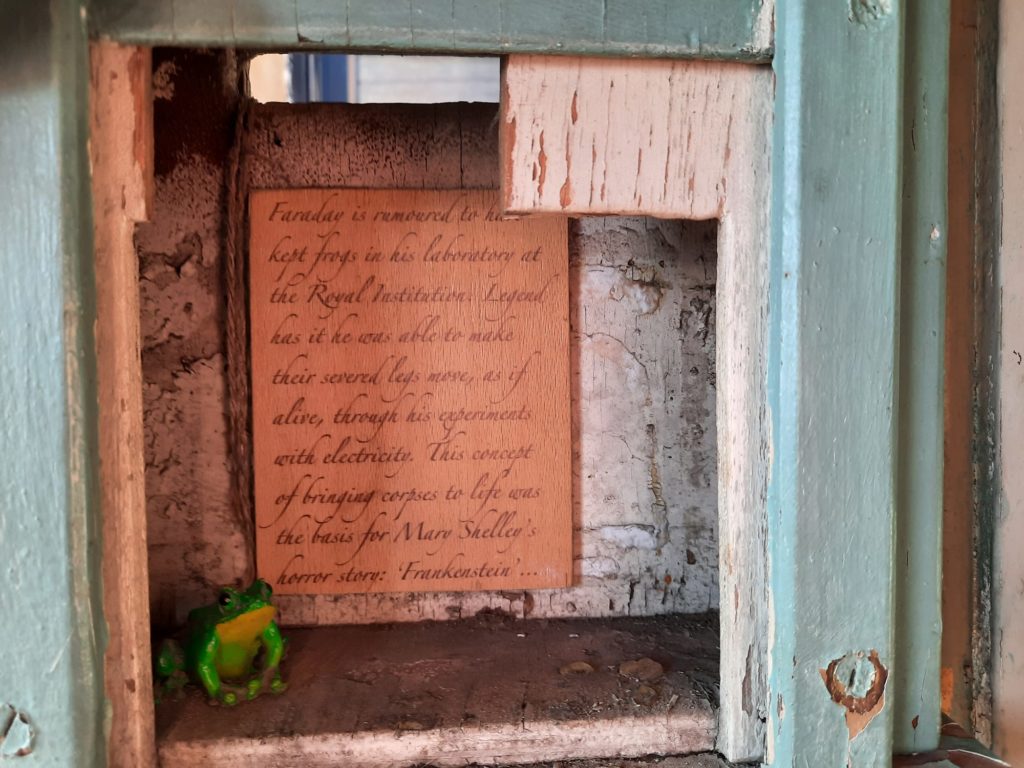

The Faraday Effect, an immersive installation by Ana Ospina and Fourth Wall Creations, pays homage to this work. It takes the form of a little wooden hut, big enough for a couple of people at a time. Inside, visitors are encouraged to poke around, opening doors and shutters to learn more about Faraday. There’s information on his impoverished childhood, famous experiments, and time at Trinity Buoy Wharf. It’s the sort of place that’s great if you get it to yourself (or yourself and the Urban Geographer). It gets a little less comfortable if you’re there at the same time as a stranger, reaching around each other to find the next information panel. Good fun in any case.

And overall that was my impression of Trinity Buoy Wharf. Good fun. Although the visit is a little short without access to Longplayer, I nonetheless enjoyed the blend of old and new, and focus on historic interpretation. I would like to return during the summer when there is apparently an outdoor bar, and I can chill out while listening to those celestial sounds.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.