Nelson’s Dockyard and Dockyard Museum, Antigua

Nelson’s Dockyard and the Dockyard Museum are must-sees for anyone visiting English Harbour in Antigua. A pleasant spot to take in the area’s many layers of history.

Nelson’s Dockyard

To begin with, Nelson’s Dockyard wasn’t Nelson’s Dockyard. It was just a regular dockyard, part of the naval infrastructure at English Harbour. And of course if we go back further, English Harbour wasn’t English Harbour, but was something else to the Siboney or Arawak-speaking people. But that is a story for another day: our story begins more or less when the British acquired Antigua and Barbuda in 1632.

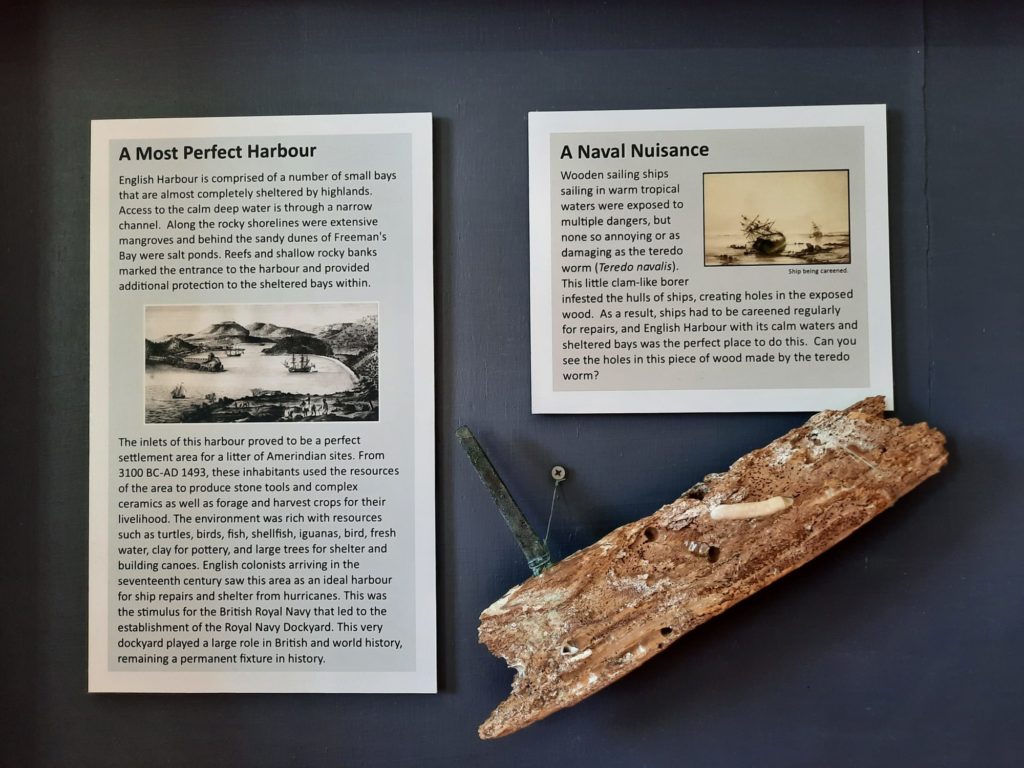

Antigua, the more easily inhabited of the two islands, has a lot of natural harbours. Nearby Falmouth Harbour was amongst the first settlements (I’ve been to both and it’s not much like the original). What became known as English Harbour was an excellent spot indeed. It was a good place for ships to shelter during hurricanes. It’s on the south coast of the island, where you can keep an eye on the French at Guadeloupe. And it’s relatively easy to defend.

The first recorded ship to enter English Harbour was the Dover Castle in 1671, after a spot of pirate chasing. By the 1730s there were forts to protect the harbour, and it was in regular naval use. As we learned in this post, Horatio Nelson (not yet Lord) was in charge here between 1784 and 1787. But he was a stickler for the rules and nobody liked him. He didn’t like them either, calling this place an “infernal hellhole”. A bit dramatic, perhaps.

What is now Nelson’s Dockyard was built from the 1740s, using enslaved labour. The last buildings date to the 19th Century. It was a bustling place for a time, but the decline of the sugar industry in the 19th Century (for various reasons including cheaper sugar from beets) led to a similar decline in English Harbour. The Navy abandoned it in 1899.

Dockyard Museum

As is so often the case, decline and neglect can sometimes lead to preservation. Buildings aren’t replaced because of low investment, and if they last long enough in that condition they become ‘historic’ and worth saving. That’s precisely what happened here, and today Nelson’s Dockyard is the only remaining Georgian dockyard in the world. Various supporters recognised its value starting from the 1920s, and restoration of individual buildings began in the 1950s. It opened as a historic site in 1961.

The story of the dockyard is told today in the Dockyard Museum. It is housed in one of the newer restored buildings: the Naval Officers’ and Clerks’ House dating to 1855. Following a restoration in the 1970s, it opened as a museum in 1997. Because the ‘Antigua Naval Dockyard and Related Archaeological Sites’ are a UNESCO World Heritage site with an entrance fee, you need to have a ticket (or be staying at a Dockyard hotel) in order to access the museum. A separate donation for museum upkeep is then encouraged.

Part of the UNESCO listing references how Nelson’s Dockyard shows the adaptation of Georgian (or later) prototype buildings to the Caribbean climate. The museum is a good example. It is a two-storey building with big colonial wrap-around verandas. Climate control inside is achieved by opening the windows to let in the sea breeze. It’s cool and shady enough to feel like a respite after a sunny walk around the rest of the Dockyard. It’s a very charming space.

A Complex History

The Dockyard Museum is very much a local history museum. Only that history is inextricably global. The British colonised Antigua because it was a good place to make a lot of money. Primarily in the sugar trade. Plantation owners offered English Harbour to the Crown because they hoped they would get better protection of their interests. They continued to have to invest their own resources in developing and maintaining the naval base here, including the labour of enslaved workers. A lot of global forces were at play, therefore, in this small corner of Antigua.

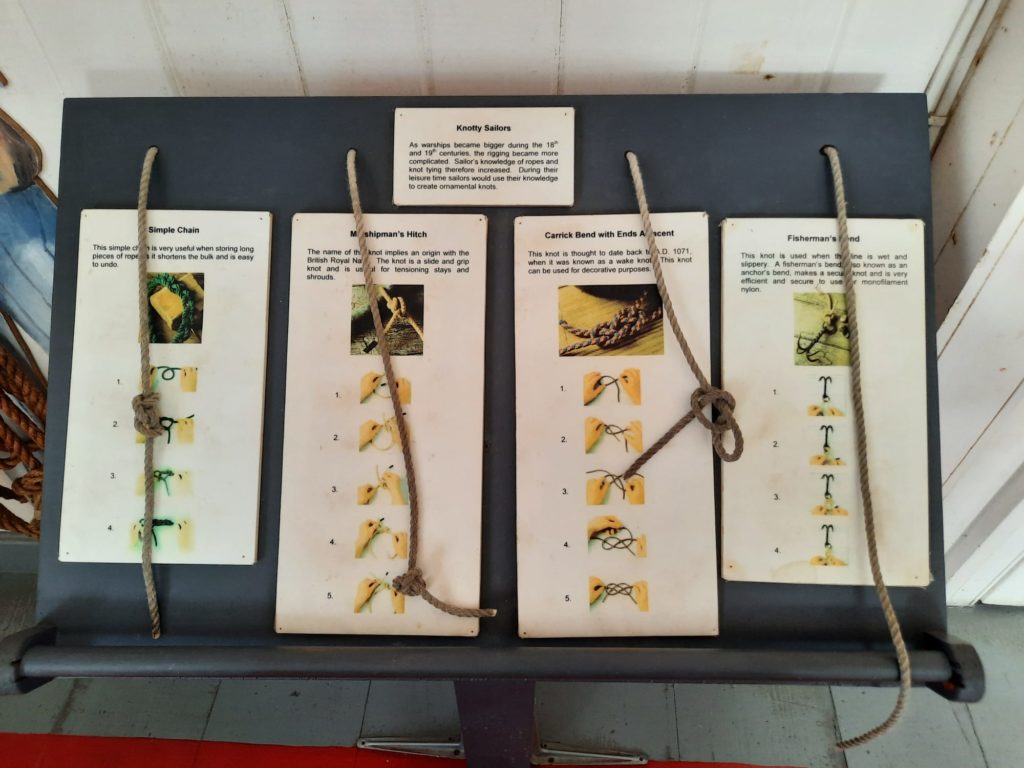

One thing I found interesting in the Dockyard Museum was the extent to which they have incorporated contemporary perspectives in what is a relatively old-fashioned museum. And in case you worry this is pejorative, the Salterton Arts Review almost always means old-fashioned in a positive sense when it comes to museums. I like the glass cases of objects and accompanying wall texts. The few interactive exhibits are also low-tech, like a knot-tying activity. It’s a sensible way to provide a pleasant visitor experience. And doesn’t involve too much overhead in the form of technology or staff to watch over more accessible artefacts.

But this doesn’t mean the texts or perspectives are old-fashioned. In particular, wherever enslaved labour was integral to a part of dockyard life, this is generally called out. And if an enslaved person’s name is known from records, you will normally find it within the text. The temporary exhibition when we visited, The Eight, is a good example. It forms part of the 8th of March Project, a community-oriented, interdisciplinary project to restore the names and stories of enslaved workers in and around the dockyard. Its focus is an explosion in 1744 which killed a number of enslaved workers: Billy, London, James Soe, Caramatee, Quamono, Dick, Joe, Scipio, and Johnno.

Final Thoughts On Dockyard Museum

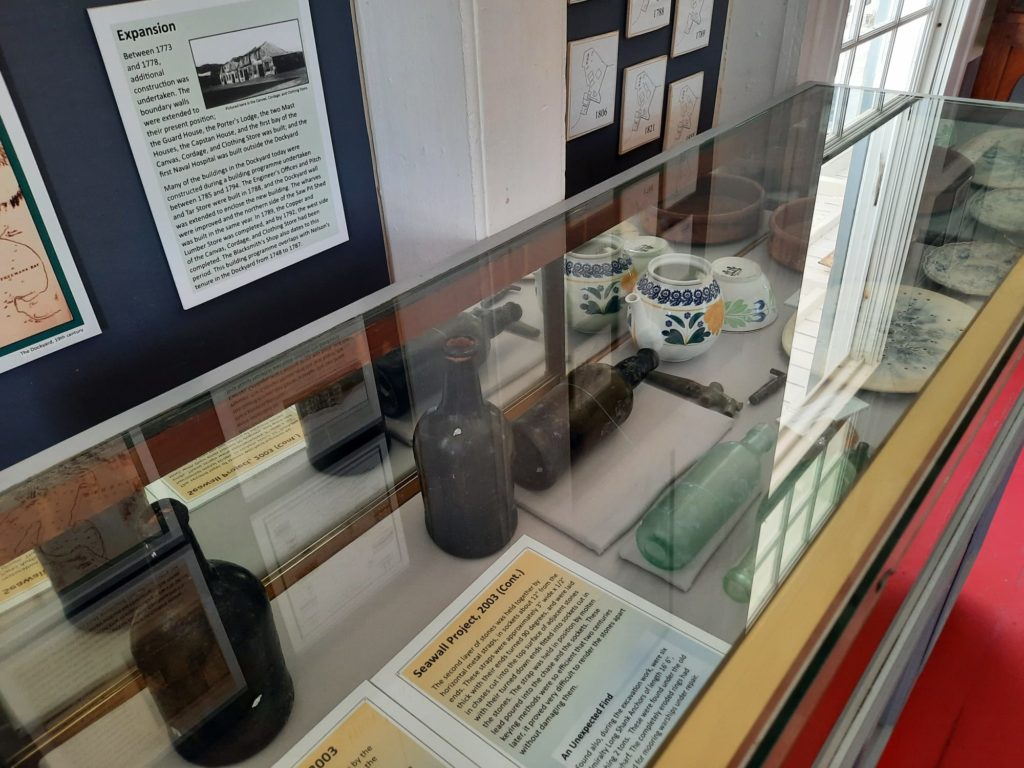

I very much enjoyed the experience of visiting the Dockyard Museum. I loved learning about life on ship and shore. Excavated archaeological artefacts go right back to pre-Columbian life in the region, through to the clay pipes and pottery sherds you might find mudlarking in London. Objects and texts give a good sense of what life was like here, from uncomfortable camp beds to the relative lack of women to sanitary conditions and disease.

I’m not just saying this as a museum lover: if you’re in English Harbour I recommend going to Nelson’s Dockyard, and if you’re in Nelson’s Dockyard I recommend going to the museum. It’s a unique spot, with an interesting history. Without reminders like this of where the story began, it’s perhaps a little too easy to get wrapped up in beaches and cocktails and admiring fancy yachts. An hour or so in the museum is a good balancing activity and a way to get a perspective on what makes this place unique.

To continue your exploration, there are several options. Once you have access to the national park, you can also visit Dow’s Hill Interpretation Centre, Shirley Heights and Clarence House. You can take a historian’s approach and find opportunities to join tours and see inside. Or you can do what I did and go to the regular Thursday party at Shirley Heights (or Sunday but it’s much busier), followed by Rum in the Ruins at Dow’s Hill on Friday. Having a cocktail in hand doesn’t mean you can’t look around at ruins or restored buildings, and take in the strategic value of a lookout point like Shirley Heights. I also recommend a short hike to one of the ruined forts: Fort Berkeley is easiest to reach.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.