After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art – National Gallery, London

A large-scale exhibition on modern art at the National Gallery, After Impressionism has some lovely works to offer, but slotted into a narrative that plays it rather safe. And where are the women?

A Popular Subject, A Popular Exhibition

This is perhaps my own fault: I went on a Saturday afternoon. Please somebody stop me if I ever try to do this again at the National Gallery. I knew that this would be a popular exhibition, as Impressionists and Post-Impressionists are perennial favourites. But I tend to underestimate or misremember just how over-subscribed National Gallery exhibitions are until I’m in them.

What I’m saying is, my experience of this exhibition got off to a bad start. There were so many people I couldn’t get near half the works unless I gave up on seeing them in order, and instead flitted back and forth according to the movements of the crowd. Careful curation to build a progression or a dialogue between works thus goes out the window a little. It’s almost (but not quite) worth becoming a Member so I could hopefully see these exhibitions at quieter times.

This preamble is something of a disclaimer. As you read the paragraphs below, keep in mind that I was not having the best time. Then again, this is all part of putting together an exhibition: anticipating visitor numbers and ensuring the best possible visitor experience, avoiding bottlenecks and creating a narrative that is strong enough to survive the audience following a different path. But enough grumbling, on now to a proper introduction.

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art

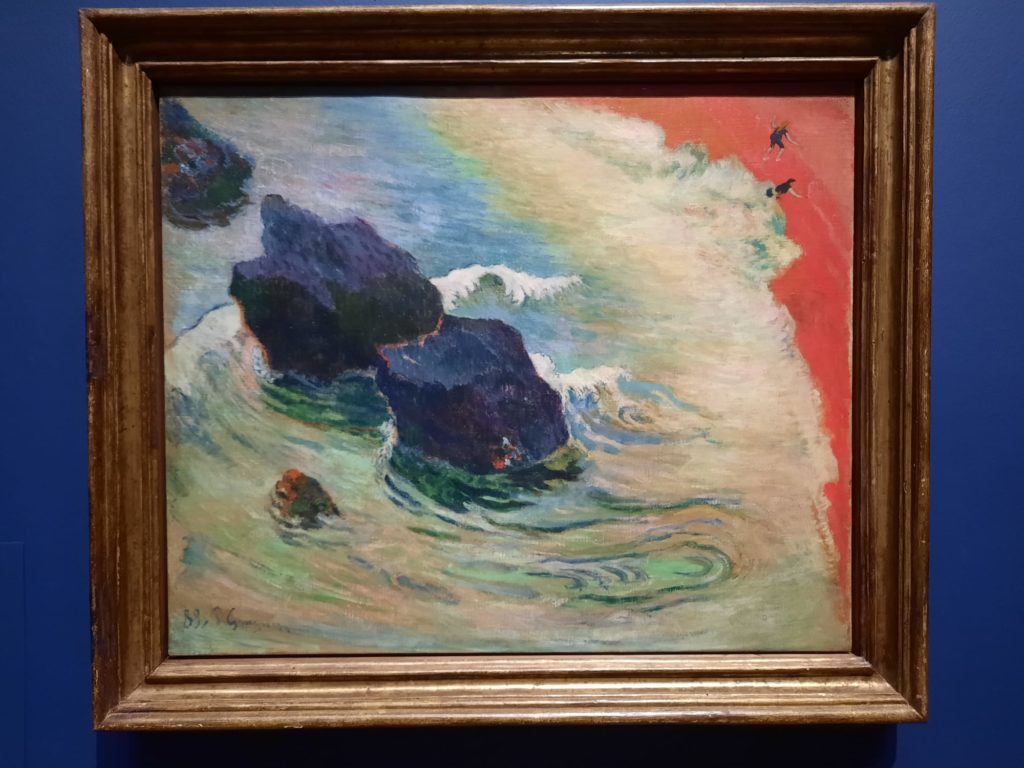

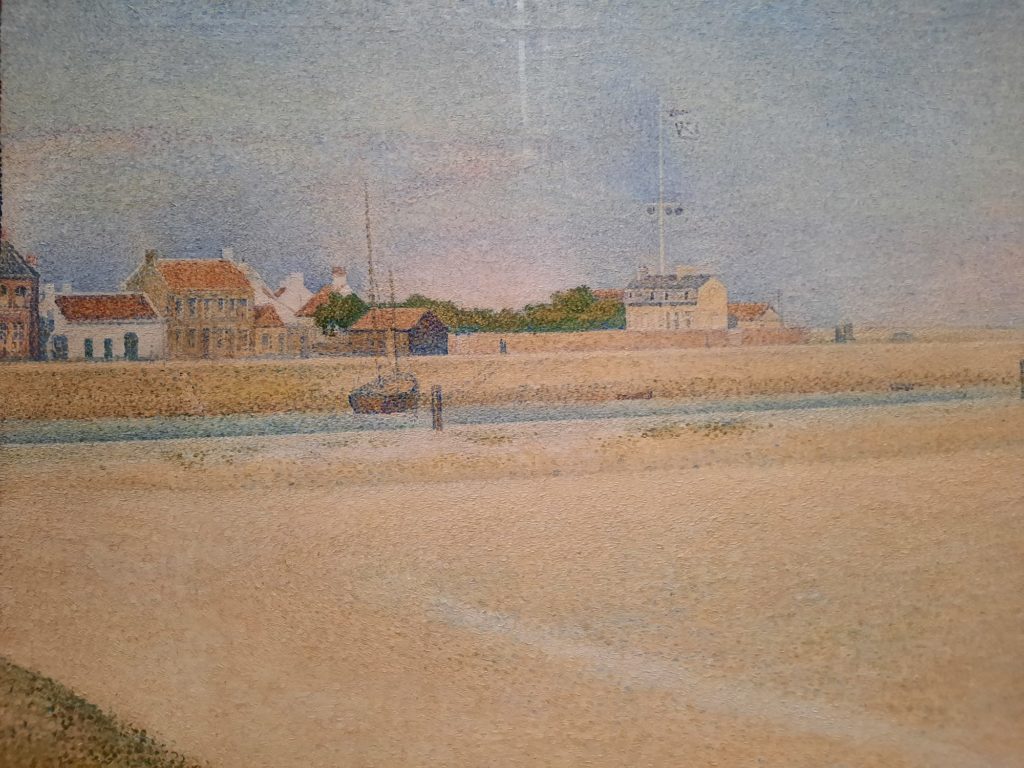

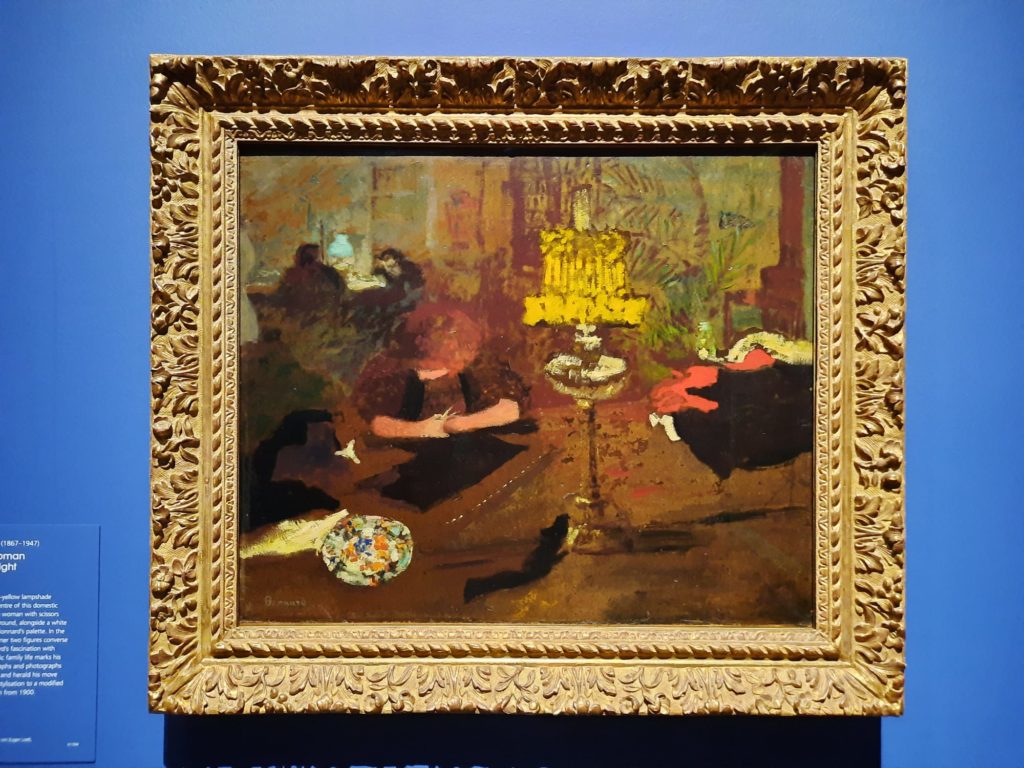

As the name suggests, After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art takes as its subject the transition from Impressionism into modern art movements. It’s thus a chronological and fairly linear exhibition. It starts with some of the forefathers (like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Rodin), deep dives into Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin, swells a little to include other European centres, before it’s back to Paris and closing out the show with Picasso, Derain and the rest.

The first room has highlights from these forebears of modern art. This is where it was so busy I had trouble concentrating on the artworks and the story. I wasn’t until I got to the next room and spotted some uncrowded Van Goghs that I began to relax into it. If nothing else, After Impressionism has some really excellent and seldom seen loans from private collections which make it worth seeing. The Van Goghs are exceptional.

The three artists selected do demonstrate the bridge between the Impressionists and modern art: the strands of precise dismantling of colour and shape vs. Expressionist moods and compositions. They are supplemented by works from a few other artists such as Degas, but plenty more could have been included. This is actually one of the most interesting lenses through which to view this exhibition: what and who is included or excluded?

Who Makes The Cut In The Story Of Modern Art?

Other than the overcrowding, the main drawback for me of After Impressionism was its conservatism. In 2023 it feels too simplistic to present such a linear art historical narrative. You could come away from After Impressionism really feeling that the important developments in Post-Impressionism/modern art all happened in Paris. There are small focuses on art from Barcelona and Brussels, and from the Vienna Secession and Germany, but they feel like footnotes. You could also be forgiven for thinking that only male artists are important in the story of modern art.

Contrast this with a couple of exhibitions I’ve seen in the last year or so. Surrealism Beyond Borders at Tate Modern demonstrated all the ways in which that art movement, which is also often associated with Paris, happened in a multitude of ways all over the globe. And abstraction, which often conjures images of mid-century American men, was reclaimed for a plethora of women in Action, Gesture, Paint at the Whitechapel Gallery.

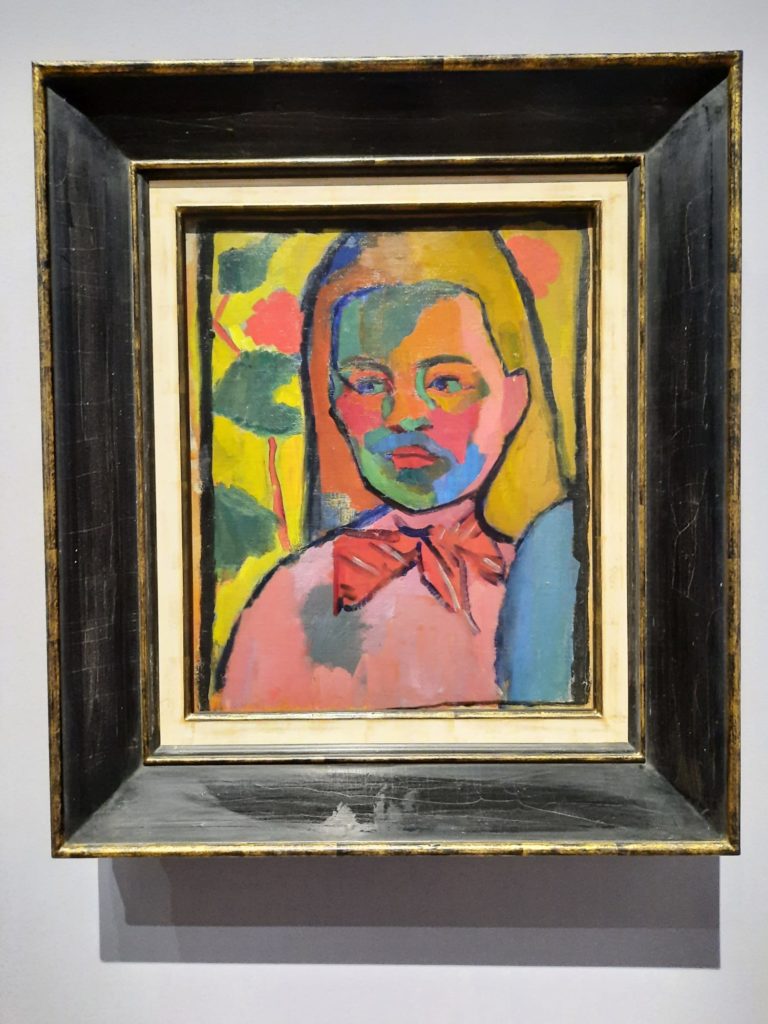

Both of these exhibitions suffered from a very different problem, which is editing down from the whole world to a manageable exhibition. But the point for me is that it’s a little disappointing to go to the National Gallery and hear once more that the story of modern art is a story of French men. The lack of women is noticeable – I called my partner over about halfway through the exhibition to point out the first work by a female artist (Käthe Kollwitz). There are only about half a dozen works by women in the whole exhibition, hardly any of them living or working in Paris.

Back To The Art

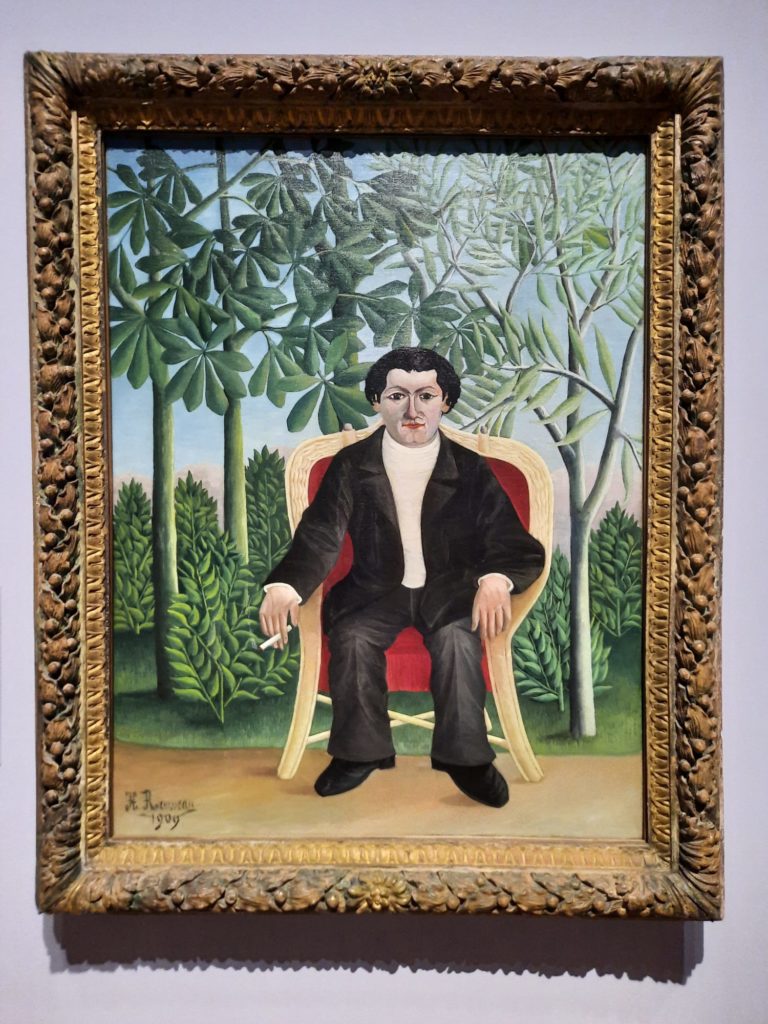

Putting aside these gripes once more, let’s take a look at the paintings and what they tell us. I’ve already mentioned that there are some great loans from private collections. There are a high proportion of loans in general: the best collections of art from these movements tend to be in France or the US. Some I’ve seen several times before: there is a sort of ‘greatest hits’ for exhibitions of this type, for instance the red-hued painting by Degas of a woman having her hair brushed from the National Gallery’s own collection.

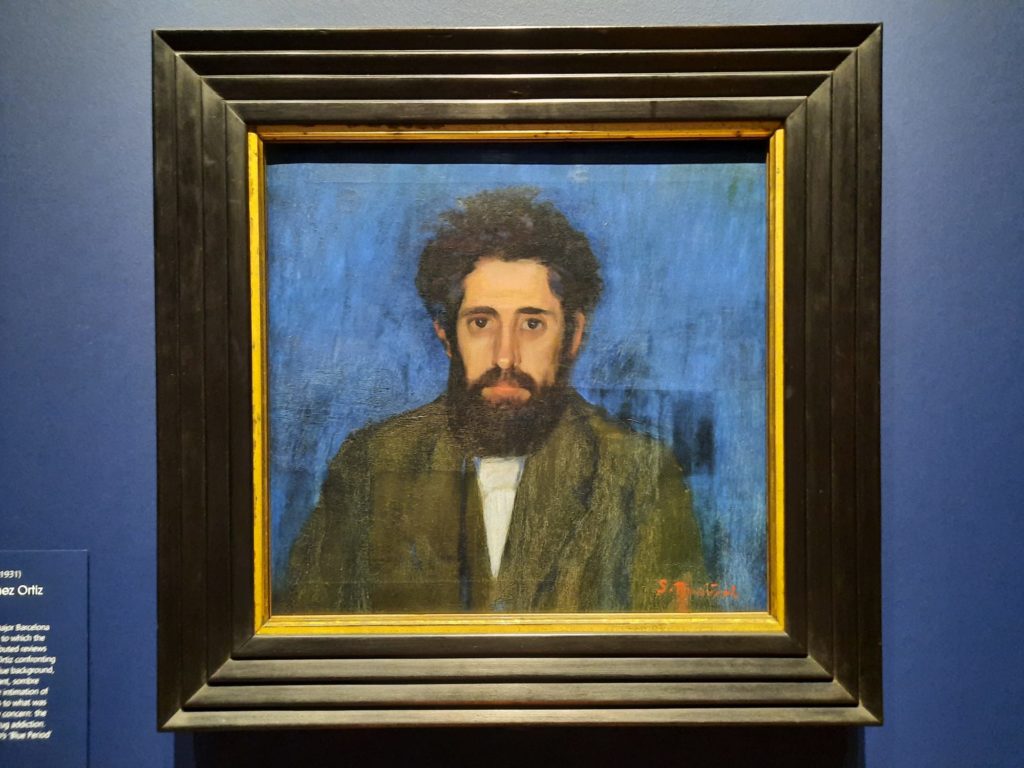

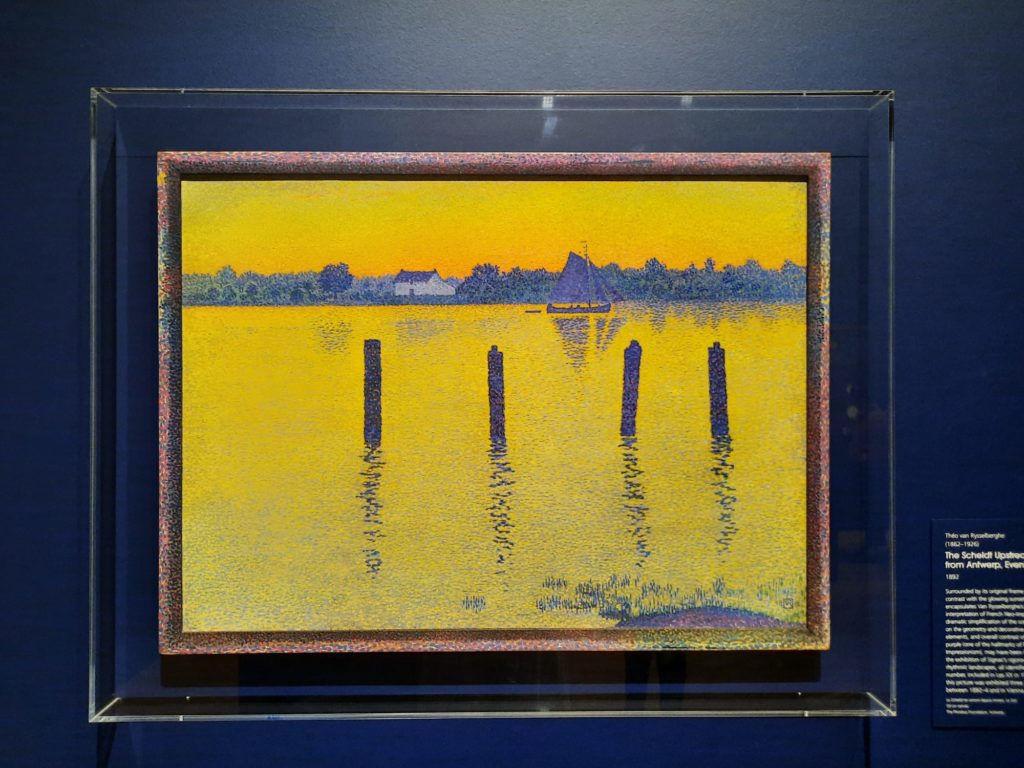

What were really interesting for me were the European sidetracks in the main narrative. I’m not entirely sure why Barcelona and Brussels were paired. But it does put an unusual Picasso into a different context from that in which he is usually seen. I enjoyed a painting of a female motorist (definitely modern), and the vivid purples and yellows favoured by Belgian post-Impressionist painters. Elsewhere the clean, calm lines of the Vienna Secessionists gave a quick glimpse into their Gesamtkunstwerk philosophy.

Nearing the end of the exhibition, there are some interesting indicators of future directions in art. I didn’t expect to see a 1911 nude which would remind me strongly of Lucian Freud, the artist who I last saw in these galleries. Entering the final room, there’s a sense of the fragmentation (finally) of one art historical story into many different threads.

Rethinking Post-Impressionism

It’s easy to be critical, sometimes. Say I were a curator rather than an armchair critic, what would I have done differently? I think perhaps I would have preferred a less chronological structure. Because the essential argument isn’t wrong: you can see precursors to modern art in the likes of Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin. A continuation of the Impressionist landscape, for instance. Or Cézanne’s fruit bowls taken to their logical conclusion, Cubism.

So I think what I’m saying is I would have responded better to deep dives from these beginnings into their modern art manifestations. Take a few examples and see how they play out in different contexts. Colour, form, themes. This shift may have allowed for the multiplicity of voices, both geographically and gender-wise, that I felt I was lacking.

To those who would argue that this viewpoint is too ‘woke’: fine. The other angle from which I approach this is: what does an exhibition add to the discussion? That modern art came out of Impressionism isn’t really up for debate. Seen from that perspective, this show at the National Gallery confirms what we already know. Supplemented slightly perhaps by the forays into other European centres, but these blind alleys would in my opinion have been the meatier contributions if fully explored.

Final Thoughts On After Impressionism

Clearly, if you’re anything like me, you should pick a quiet time to see After Impressionism. I would have reached the same conclusions, I think, if I’d had more space and time to contemplate. But I might have been less grumpy while doing so. Perhaps a quiet weekday morning would be the optimum time.

As I mentioned somewhere above, I think for me this exhibition demonstrates the difficult task of the curator. In somewhere like London, and somewhere like the National Gallery, audiences can be hard to please. There are so many excellent institutions and exhibitions that we want it all. It’s not enough to bring us magnificent paintings. We want new ideas, and ideally inclusivity to boot. Framed another way, the UK’s national institutions have something of a duty to further debate and to help audiences to see themselves in our national art collections.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art on until 13 August 2023

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

The colour and brushwork is staggeringly good, isn’t it. I love the unseen ones – better perhaps than the public ones..?…or just novel?

I have been a big reader of exhibition labels for years, and I love the ones from private collections. Something about added scarcity value, I think, and the feeling of seeing what is normally a private indulgence.

Great you very much for sharing this with us; I truly enjoyed it. Beautiful pieces can be seen in the National Gallery’s After Impressionism, a sizable modern art exhibition, however the storyline plays it very safe. Where are the women, anyway? Given the enduring popularity of Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, I anticipated that this exhibition would be well-received. However, unless I’m in one, I usually underestimate or misremember how packed National Gallery exhibitions are. For those like me who want to learn more about it, it can be incredibly beneficial. If possible visit this website Joshuacreekarts.com to gain more idea or tips on the same.