Souls Grown Deep Like The River: Black Artists From The American South – Royal Academy, London

A moving exhibition of art from the Southern United States, Souls Grown Deep Like the River is both thought-provoking and revelatory.

Souls Grown Deep Like The River

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes – Poems | Academy of American Poets

What a fascinating exhibition. I mean this in several different senses. The art, of course. The Souls Grown Deep Foundation from which the majority of the works are loaned. The fact of a White art collector supporting and promoting the work of Black artists. The questions that may arise as a result. The classifications of art outside the mainstream (‘folk’, ‘vernacular’, ‘outsider’) and the various ways in which those words are loaded. The line between ‘art’ and ‘craft’ and where ‘women’s work’ falls (which I’ve touched on before).

As the full title suggests, Souls Grown Deep Like the River is an exhibition of art exclusively by Black artists. And even more exclusively by those living in the Southern United States. There’s a significance to this. Many of us will be aware of the so-called Great Migration of millions of Black Americans from the South to the North in the early 20th-Century. It led to new ways of manifesting creativity, including the Harlem Renaissance. And nobody can be unaware of the huge influence of Black musicians from the Southern states on 20th Century and contemporary culture.

But what about the artists, not musicians, who didn’t migrate? That is precisely the question this exhibition aims to draw attention to. In a cultural sphere like art which is more closed than music, how can we understand the art produced in the South by Black artists? It’s a really, really interesting question. I want to dig into it a little further after explaining more about the exhibition itself.

Bringing The Souls Grown Deep Foundation Into The Establishment

We (or I at least) don’t often reflect on this, but the Royal Academy is literally the establishment when it comes to art in the UK. The body which for hundreds of years has decided who is on the inside and who is not. The Summer Exhibition is more inclusive than it perhaps once was, but for many years it was the last word in mainstream artistic taste. So it seems symbolic that this exhibition is here, hung on these hallowed walls.

Aside from this symbolically unusual angle, the exhibition itself is actually fairly classic, even ‘safe’. It’s in the smaller upstairs exhibition space at the back of the RA (where we saw this and this). Groupings of artists are presented together on white walls or plinths, in standard exhibition format. Explanatory wall texts add more depth. A video helps us to understand the context of ‘yard shows’, outdoor exhibitions of assembled artworks.

I can’t help circling back a little bit to this interesting point: is the process of appreciating artists who have not worked within the artistic mainstream one of inviting them into the museum space on the art world’s terms, or of broadening out what that art world looks like to allow for a multiplicity of viewpoints? I would like to think the latter, but the exhibition design here points more to the former.

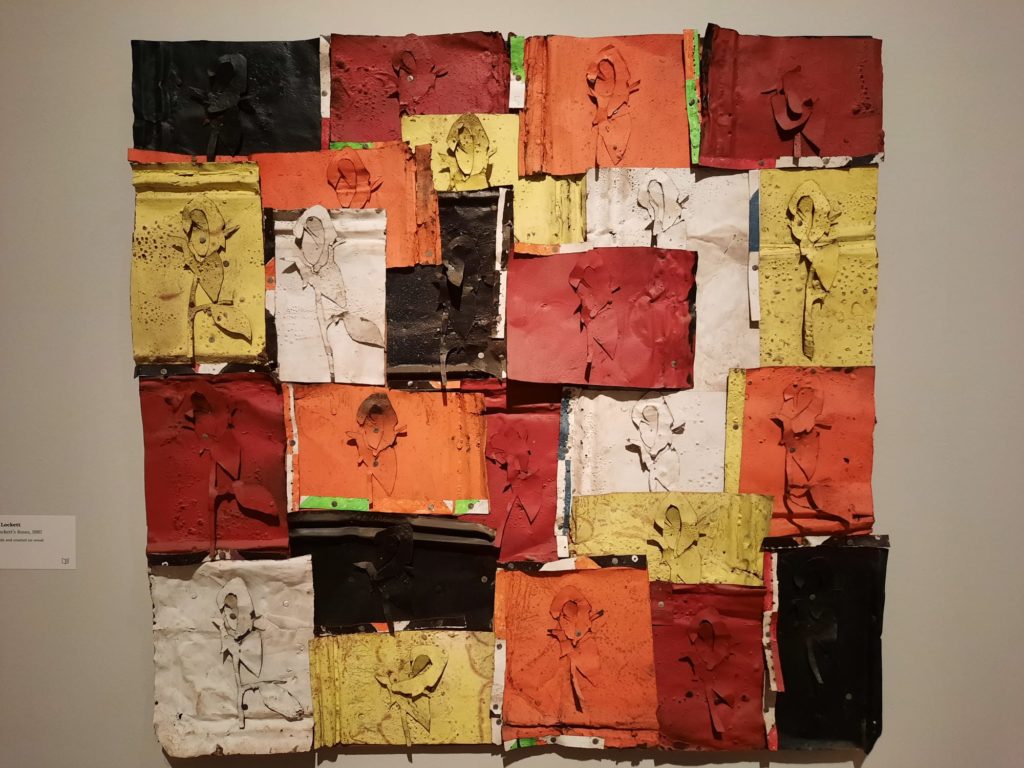

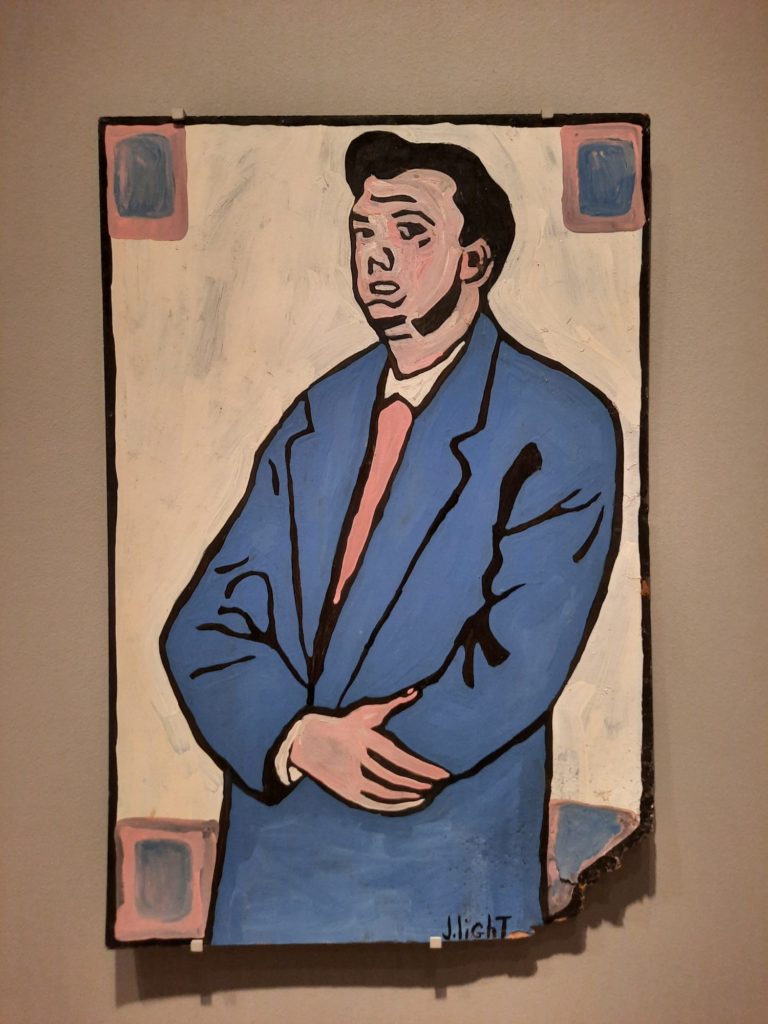

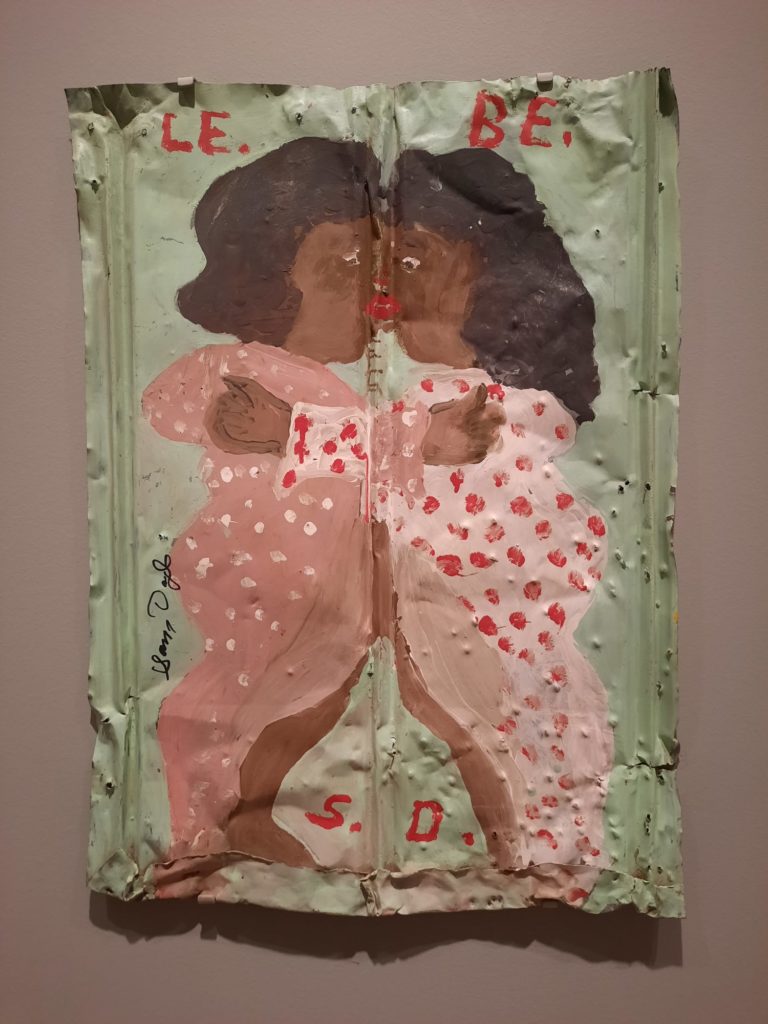

Creativity In Medium And Form

One thing that many of the artists in Souls Grown Deep Like the River have in common is a deep creativity. This manifests itself in all aspects of their artworks: the forms, colours, subjects and materials. Partly this was out of necessity. Artists even within the artistic mainstream don’t always make a lot of money for materials, even less so outside it. Although Souls Grown Deep Foundation founder and art collector William Arnett supported some of these artists with a regular stipend to allow them to explore their creativity with less financial pressure (he did this in return for the right of first refusal on the artworks produced). Nonetheless, there are a lot of found objects incorporated into sculptures or as canvases. And even some natural pigments derived from berries, grass and other readily available materials.

Many of the artists also picked up skills in their day jobs which can be seen in their art. There’s plenty of skilled welding on display, and carving skills which have their origins, for instance, in making grave markers. It’s a testament to that sort of creativity that I love and admire, where you just can’t help making art no matter the circumstances.

I can feel myself circling back to the philosophical questions though. Other artists picked up skills from learning a craft (even Donatello). Other artists, like Duchamp, worked with found objects. My question is: is that the same? If Mose Tolliver created sculptures out of available materials through necessity, is that a different type of art than Marcel Duchamp who deployed them conceptually? If Mary T. Smith‘s simple portraits have something of the Jean Dubuffet about them, do we focus on the similarities of form or the differences in origin?

Insider Or Outsider?

That last paragraph above is the crux of the question, for me. How do we either bring these artists into the artistic fold, so to speak, without erasing the unique nature of the art and experience, or acknowledge those differences without being condescending or gatekeeping what art is? The sense that I get from reading a few articles on this exhibition is that there is so much fear of being condescending that we are left without a term to describe what this art is.

Certainly the available terms are loaded. Naive art is definitely out because that’s just condescending full stop. Vernacular art too. Folk art I can cope with as a historic term, but for modern and contemporary art it implies something simple and unengaged intellectually. I’ve tended to use Outsider Art in the past. But it does clearly ringfence what is inside and outside the art world. And self-taught isn’t true either: many of these artists are part of a tradition handed down in families or between artists.

It’s a tricky line to walk: to celebrate difference and history while also saving a place for these artists within the canon. The Souls Grown Deep Foundation does its best to achieve both goals. It works to place artworks from its collection within museums and galleries. This ensures at least three things: value (prices are supported by works by the same artist being in prominent collections); visibility; and diversification of museum and gallery collections. It’s a bit of a ‘playing by the rules’ strategy: if it’s museum collection that tell us what is ‘art’, then let’s get more Thornton Dials, Lonnie Holleys and Rachel Carey Georges in there.

Final Thoughts On Souls Grown Deep Like The River

There’s a lot more I could go into. I loved that the finale of the exhibition was a selection of Gee’s Bend quilts, for instance. I’ve seen a commercial exhibition of work by this remarkable group of women before. And am fascinated by the interplay between art, craft, and practical object. Or we could consider further what it means that this championing of works by Black artists is the legacy of a passionate and dedicated White collector.

For these reasons and more, I suggest that you get to the Royal Academy before the exhibition closes. The works speak for themselves on an aesthetic and emotional level, despite the somewhat vanilla exhibition design. And there is just so much to see and to think about, so much to provoke thought and expand the horizons.

I leave you with an image. It’s Thornton Dial’s 2008 work, Blue Skies: The Birds that Didn’t Learn How to Fly (see a similar work here). What looks at first like laundry hanging out to dry is on closer inspection a series of dead birds rendered in mixed media. Metaphorically, of course, we think of the victims of lynching, which is not as far in the past as we would like to believe. Works like this demonstrate better than words can the power, rich imagery and inspired techniques employed by this varied group of artists. That the Souls Grown Deep Foundation have given us the opportunity to see them right here in London is a privilege we should not take for granted.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Souls Grown Deep Like the River: Black Artists from the American South on until 18 June 2023

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.