The Rossettis: Radical Romantics – Tate Britain, London

An exhibition at Tate Britain, The Rossettis: Radical Romantics, shows the family’s romantic side for sure. Are they radical? Maybe in some ways. Is this exhibition as much of a fresh take as it appears to be? The jury is still out.

The Rossettis: Radical Romantics

Let’s start off with a small word on names. The Rossettis: Radical Romantics is all about the Victorian Rossetti family of artists/poets. Or at least about three of their members. One is actually better known by her maiden name: Elizabeth Siddal (or Siddall). But, having married a Rossetti, she counts. Given that all three subjects share a surname the Tate refers to them throughout by their first names: Christina, Gabriel and Elizabeth. And so shall we. If you’re wondering why we’re referring to Gabriel and not Dante, the latter was an affectation. The Rossettis’ father was a Dante scholar, and combined with Pre-Raphaelite proclivities it was a perfect choice for a medievalist of Italian heritage.

The Tate proposes that the Rossettis are radical romantics. You will have to make your own mind up over the course of this review (or of course if you have the opportunity to see it yourself). They are presented as radical due to their notoriety, the revolution they brought about in the arts, and their lifestyles. The introductory text notes that “their daring stories asked questions which remain relevant today.”

This exhibition seems to posit itself as every bit as radical as they would like to believe the Rossettis are. An exhibition in a gallery which puts poetry at the forefront. Shining a spotlight on female artists and poets. Confronting uncomfortable elements of prejudice and colonialism within the Rossettis’ stories. Again, you will need to make your own mind up as to whether this is the case. I certainly did.

Who Are The Rossettis?

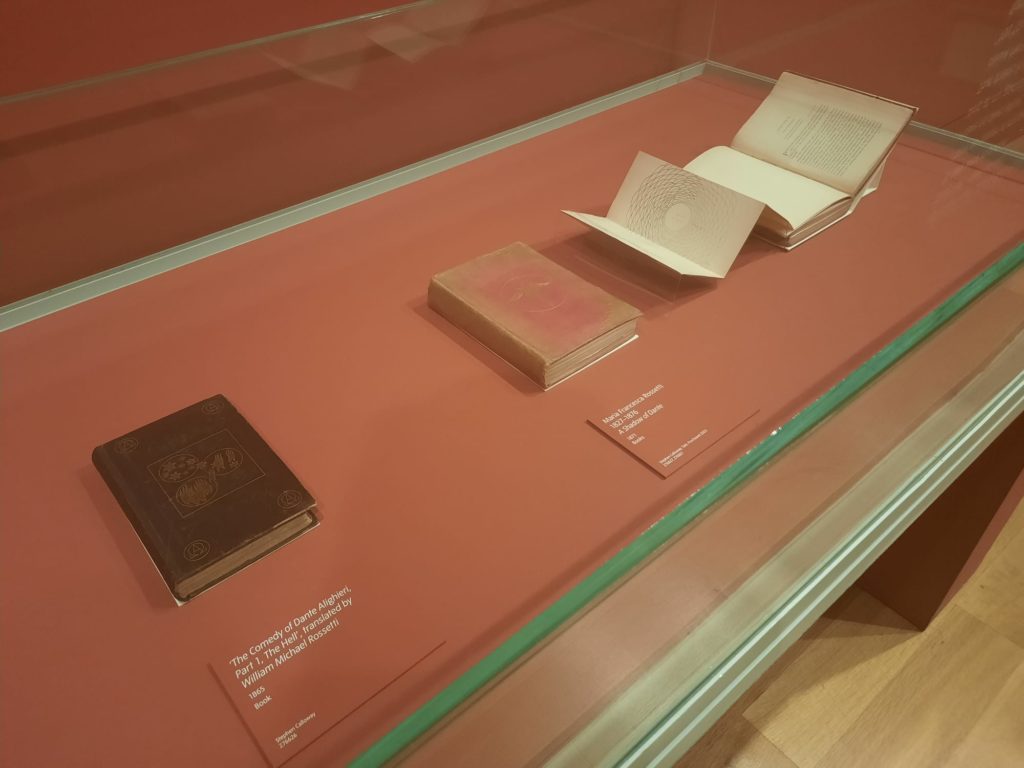

Time now to dive into a bit more of a history of this unusual family. They were, as I said above, of Italian heritage. Their father, Gabriele, was in exile in England as a revolutionary. He and his wife Frances, née Polidori, had four children. Maria, Gabriel, William and Christina were all born between 1827 and 1830 (can you imagine?!). They were encouraged in the creative arts: Maria alone didn’t take to it, although she was an essayist later in life. Both Gabriel and Christina published poems as teenagers, and some of William’s youthful artworks are also on view.

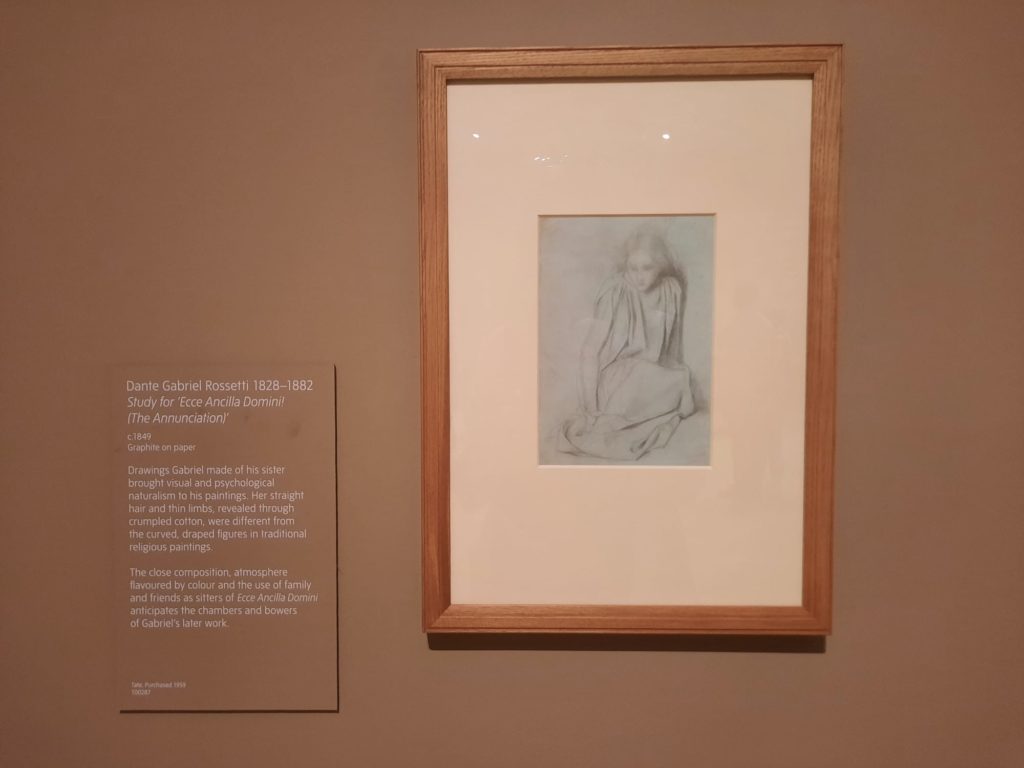

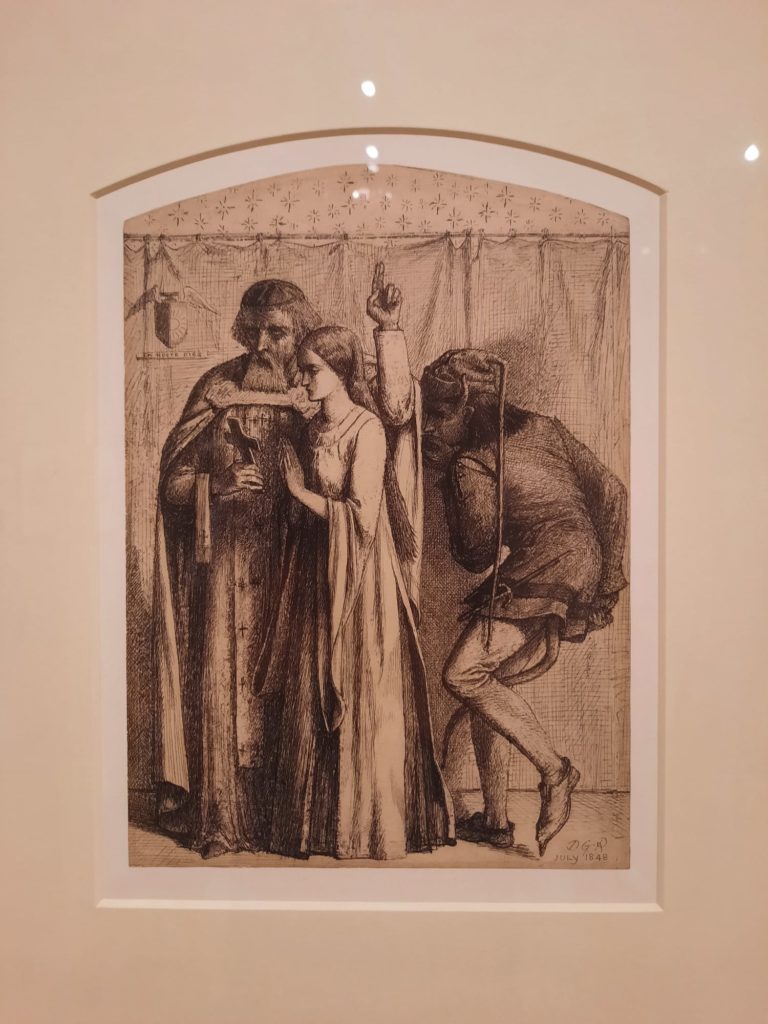

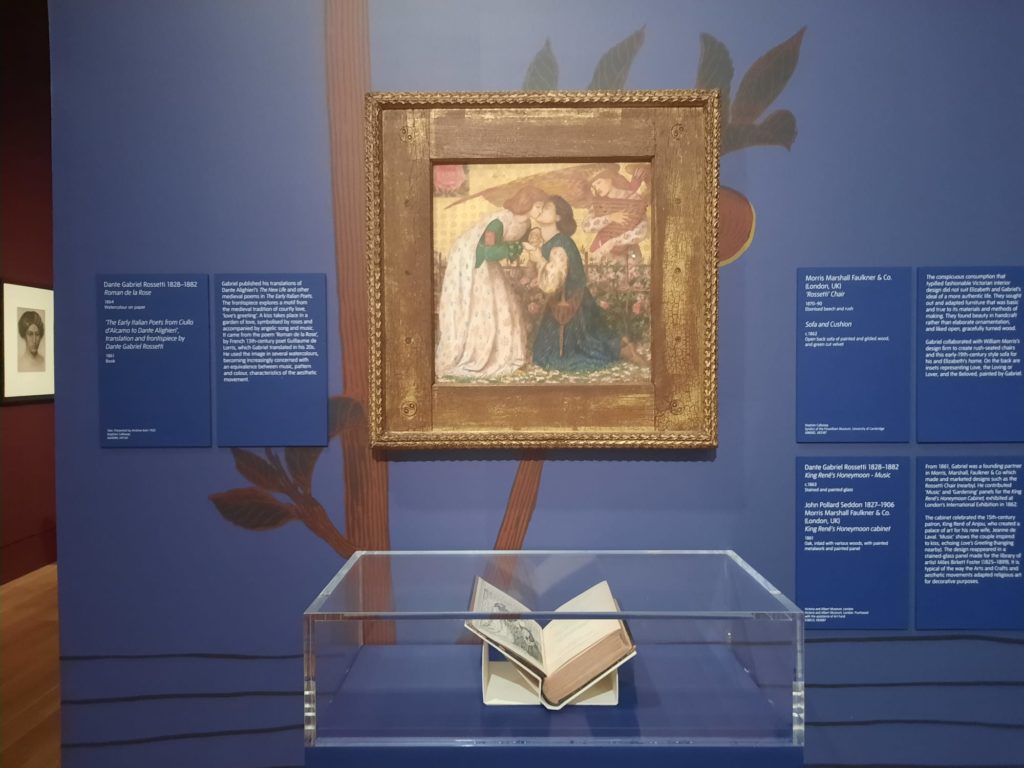

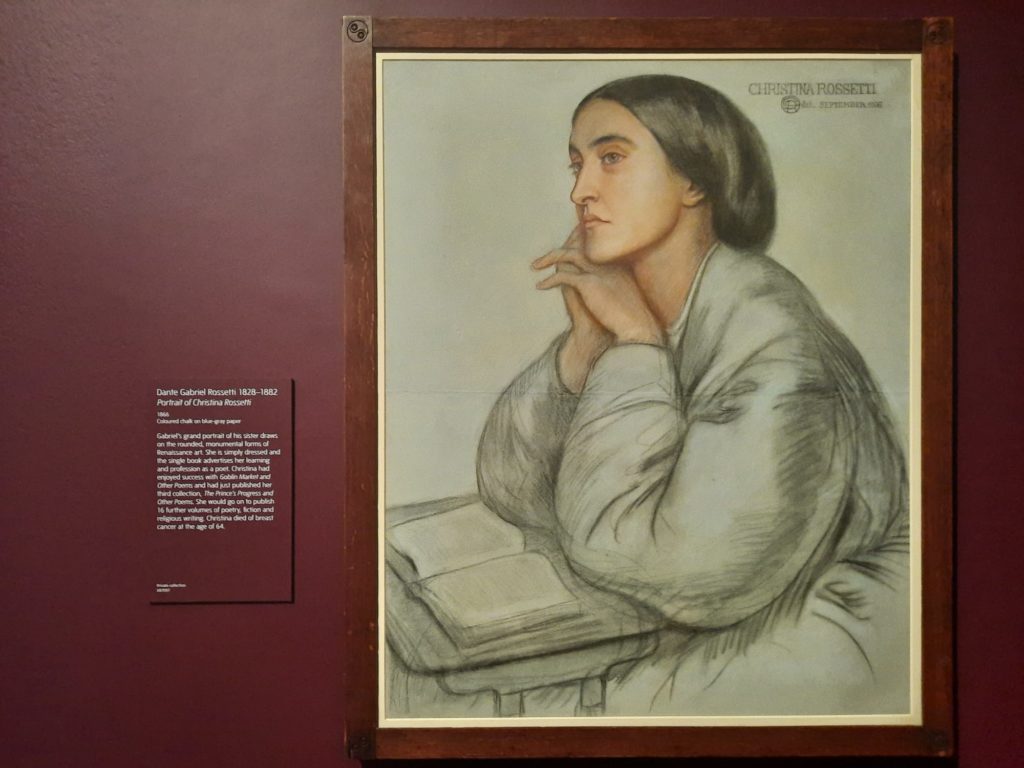

Both Christina and Gabriel were famous in their time. Christina for her poetry, and Gabriel as an artist. Along with a few fellow art students, Gabriel founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. Christina wrote poems including The Goblin Market and In the Bleak Midwinter, the latter later set to music as a Christmas carol. Their lifestyles greatly diverged, however. Christina, along with her sister Maria, never married and instead devoted their lives to Christian charity. Maria actually became a nun. Gabriel was a proper artist and bad boy. He lived boldly, had numerous affairs, and suffered from a chloral addiction in later years.

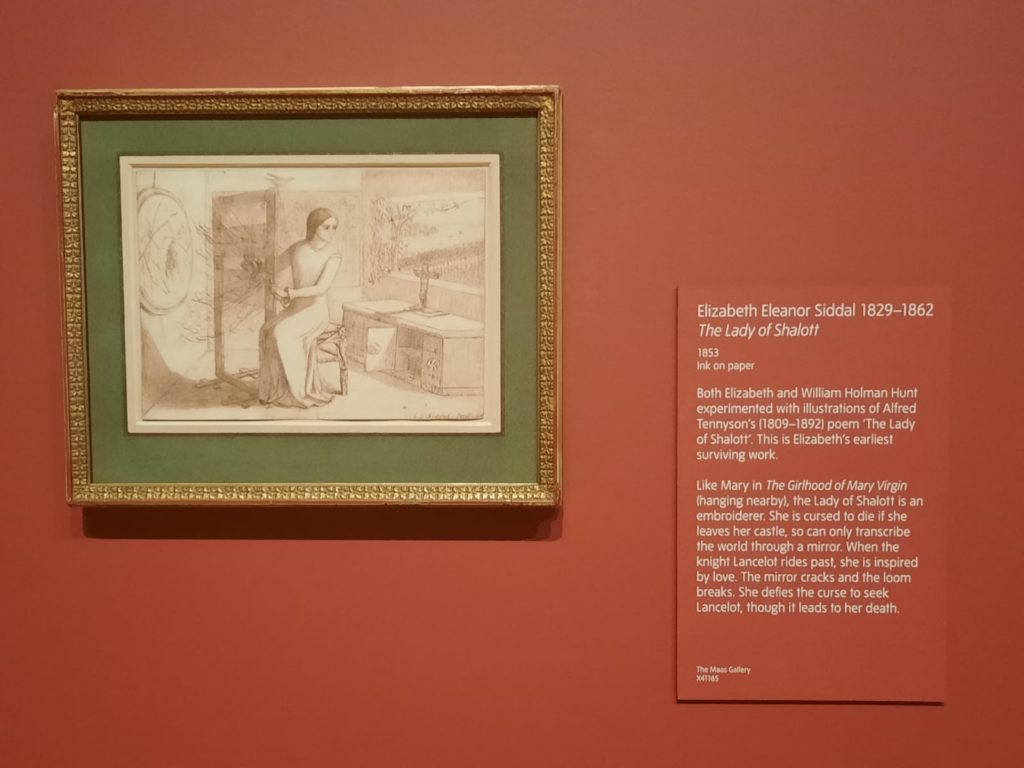

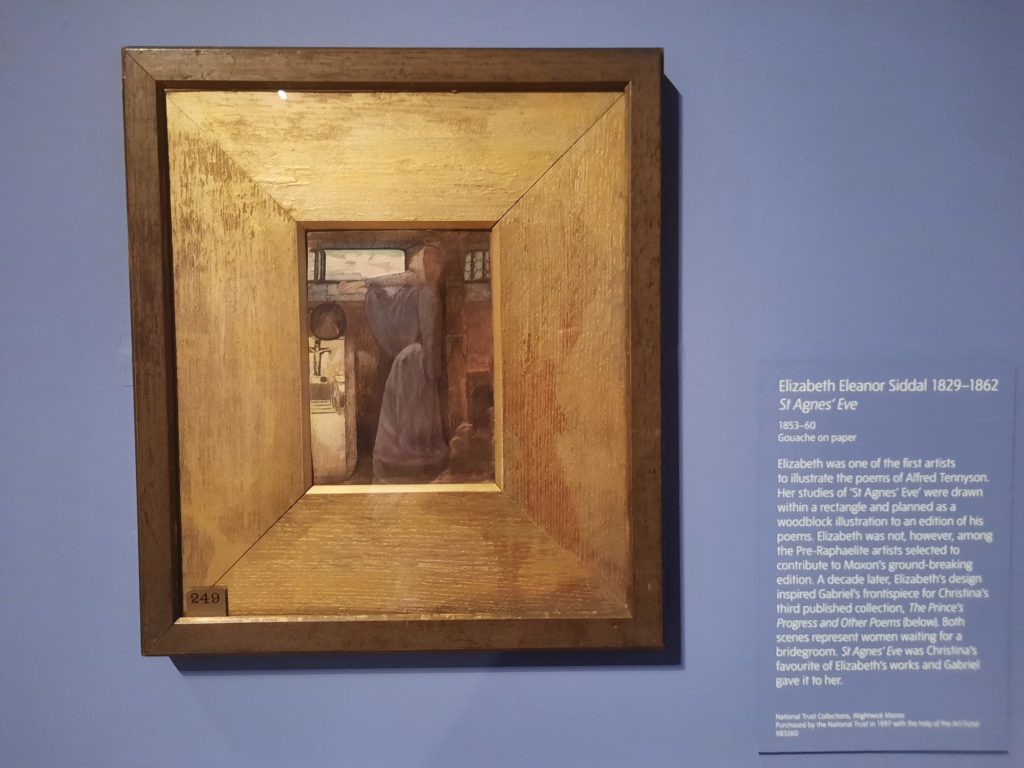

The final Rossetti included in the exhibition is better known as Elizabeth Siddal. Born in 1829, she started out as a model for the Pre-Raphaelites, before becoming Rossetti’s art student, lover, and later wife. He encouraged her artistic endeavours, and she exhibited with the Pre-Raphaelites and sold works to patrons including John Ruskin. She battled issues with mental health and addiction, however, and died in 1862 from a laudanum overdose. Gabriel famously had a book of his own poetry buried with her in Highgate Cemetery, only to have her exhumed some time later so he could retrieve it.

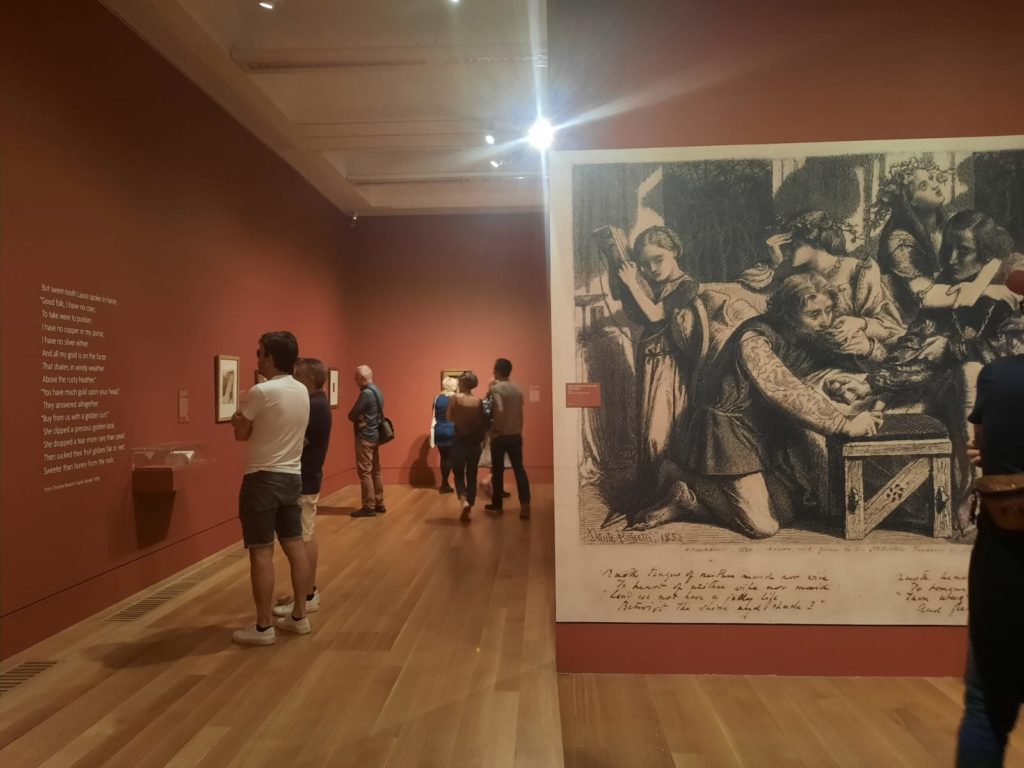

Telling The Story Of The Rossettis

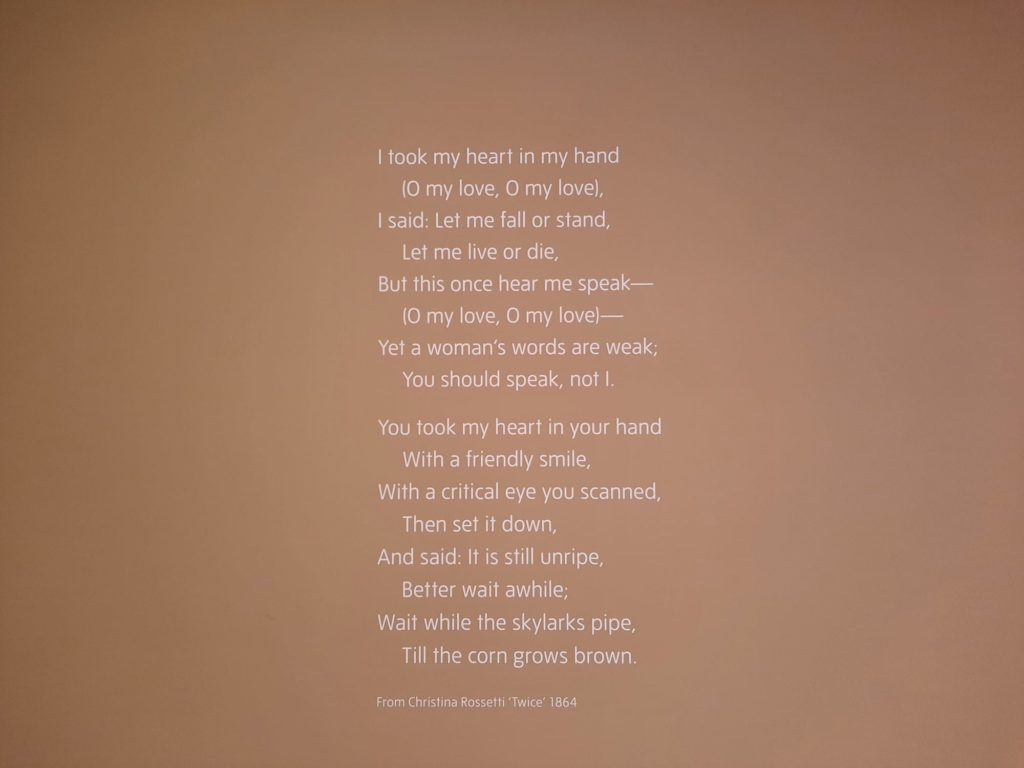

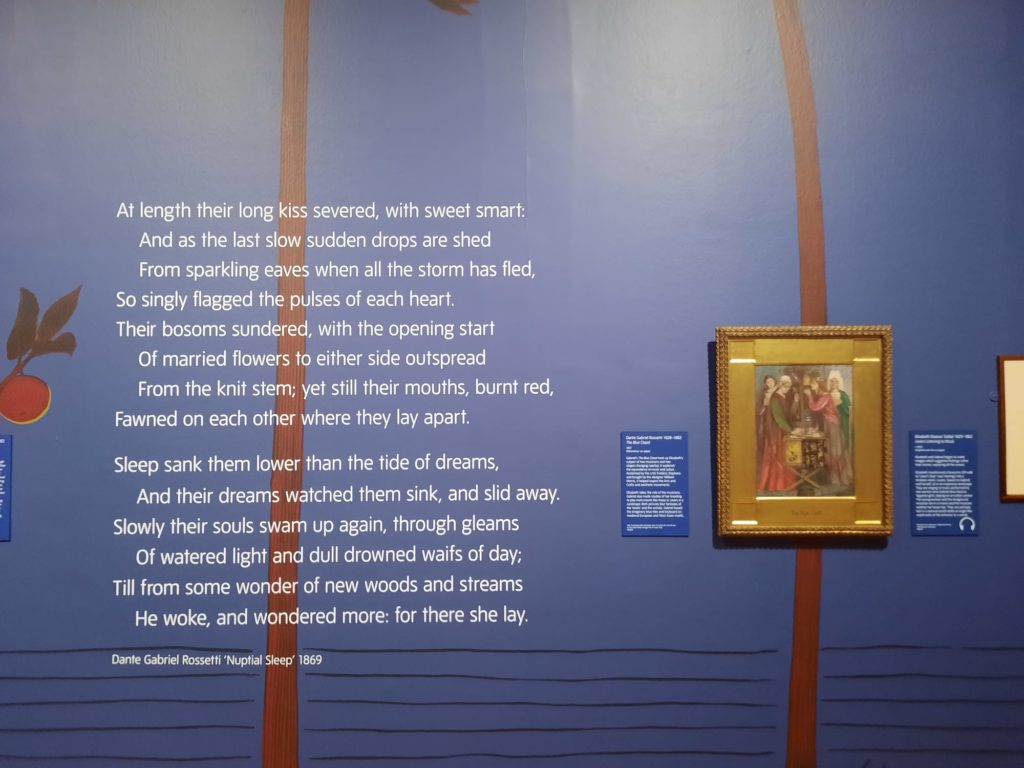

The exhibition subverts expectations in its opening gallery. Although there is a painting by Gabriel front and centre, Christina is the star of the show. You see, she is the model for the slight and frightened Mary in his Annunciation. And her poems are printed on the walls, with directional speakers playing recordings at different spots in the room. You can’t really make poems too visually interesting, but it makes the point well that, although Dante Gabriel Rossetti may be the bigger name now, in a time when poetry was more prized than it is today Christina was once the celebrity.

Moving through the rooms, the flow becomes a little more confused. It’s not organised by Rossetti, it’s not purely chronological (although it is a bit), and it’s not wholly thematic. A bit muddled, on the whole. What does happen, though, is that despite efforts to keep a spotlight on the female Rossettis, it’s Gabriel who slowly but surely becomes the star of the show. So much so that, by the final couple of rooms, it’s all his work, canvas after canvas of beauties with those Pre-Raphaelite features, the women well and truly sidelined.

Perhaps the more radical choice might have been sidelining Gabriel instead, and having an exhibition just about women in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Because as much as they liked to think themselves socially progressive, they were at the end of the day a Brotherhood, and were pretty much all middle class men. Christina almost holds her own in this exhibition, but the argument that Elizabeth’s work was as fresh or technically skilled as her husband’s falls a bit flat. The Victorian era was not kind to most women, and perhaps especially not women who started as artist’s models before marrying the artist himself.

The Works On View

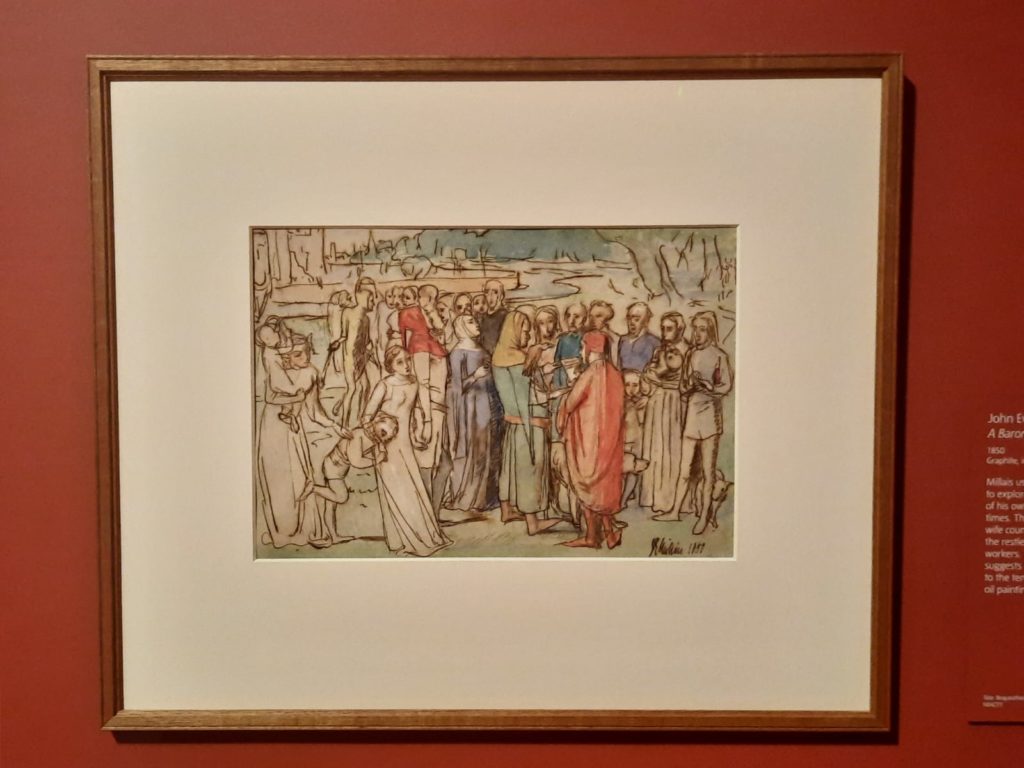

The selection of works for the exhibition is quite interesting. The Tate has quite good holdings of Pre-Raphaelite art, as does the V&A. So a lot of the works haven’t had to travel too far. The exhibition has been organised in conjunction with the Delaware Art Museum, however, so several paintings are sourced from here. According to its website, the Delaware Art Museum has the largest Pre-Raphaelite collection outside the UK.

There’s also quite a lot of printed material, not surprising as one of the subjects is a poet. There are even a handful of objects, such as jewellery used as props in some of the paintings. And the odd bit of Pre-Raphaelite furniture. I couldn’t help but thinking, however, that this Tate exhibition space is a little over-large. I’ve thought it before, for instance when I saw this exhibition. It reaches a point where you hope that the next room is the final one but it just keeps going. Some of the content thus begins to feel like filler in order to utilise the space, and the exhibition suffers a little. This is probably partly personal preference, though, as I tend to prefer small and focused exhibitions.

What I did like were a couple of instances where works have been united specifically for this exhibition. For instance, Mnemosyne, The Blessed Damozel, and Proserpine, were painted between 1874 and 1881 for a single patron. They form a definite grouping when hung together, but now reside in the Delaware Art Museum, Tate, and National Museums Liverpool. These sort of big exhibitions have the pull to bring back together dispersed works and help to recontextualise them for visitors.

What I Liked

I probably haven’t quite given this impression, but there was a fair bit I liked in The Rossettis: Radical Romantics. I have a soft spot for Pre-Raphaelite art, first and foremost. It’s not to everyone’s tast, I know, and the fashion for it comes and goes, but seeing The Pre-Raphaelite Dream, a travelling Tate exhibition from 2003, was a formative experience for me as an art lover. A lot of the later paintings here are aesthetically pleasant even if they’re not imbued with much substance beyond the models’ looks.

I did also appreciate the attempt to reposition Christina and Elizabeth against Gabriel. Whether it entirely worked is another story (more on this in a second), but I appreciated it. I liked seeing a concentration of Elizabeth’s artworks, and the careful way that Gabriel preserved them after her death. I’m not very familiar with Christina’s work, either, so enjoyed listening to some of her poetry in that first room. I wasn’t blown away by it, I have to say, but it broadened my horizons a little.

What I Didn’t Like

This list is perhaps a little longer. As I’ve already mentioned, I found the size of the exhibition a little overwhelming and felt it contributed to diluting the message. Without so many walls to fill, would the concentration of works by Gabriel vs. Christina and Elizabeth have been so high? And this was another of my gripes: I don’t like exhibitions that position themselves as recentring women but don’t quite achieve it. I felt the same way about this exhibition at the RA last year. It, too, presented an artist and their model and muse as being a creative partnership, when the power dynamics didn’t allow an even footing.

There were other claims I found stretched credibility somewhat. This included the narrative that Found, a moralistic painting of model Fanny Cornforth in the role of a fallen woman, remained unfinished because Gabriel’s friendship with Cornforth made him rethink things. I mean maybe, but he started a lot of versions so maybe he was just having trouble finishing it.

So really what I didn’t like was not so much the art or subjects chosen as the way the exhibition is structured and the arguments made. If it’s going to be an exhibition about Dante Gabriel Rossetti, then just go for it. If it’s about the women, make more of them. And there’s a way to challenge views on historic racism, sexism, colonialism etc. which doesn’t bend things quite so far to fit. I’ve had the same thought about several Tate exhibitions in recent years – perhaps a current curatorial trend or conscious positioning.

Oh, and just like this sentence, the section on the Rossettis’ legacy feels like a complete afterthought.

Final Thoughts

While this exhibition has its flaws, I’m still glad I saw it. As I said earlier, I have quite a soft spot for Pre-Raphaelites and there are some undoubtedly nice works here. I don’t feel I know the Rossettis that much better than I did. I still think Elizabeth Siddal got a slightly raw deal. But there were moments to enjoy.

To get the most out of The Rossettis: Radical Romantics, I think you have to be a real Pre-Raphaelite lover. If seeing a load of paintings of Fanny Cornforth, Jane Morris and the other Pre-Raphaelite favourites is what does it for you, then please rush immediately to see this. If Victorian art is not to your taste no matter how medievalist or aesthetic, perhaps give it a miss. I would prefer to stick to William Morris as an interesting Pre-Raphaelite case study: I may have exhausted my interest in the Rossettis here in one fell swoop.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

The Rossettis: Radical Romantics on until 24 September 2023

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.