Collection De L’Art Brut, Lausanne

Jean Dubuffet’s gift to the city of Lausanne, the Collection de l’Art Brut is a must-see for anyone with an interest in art outside the cultural mainstream.

La Collection De L’Art Brut

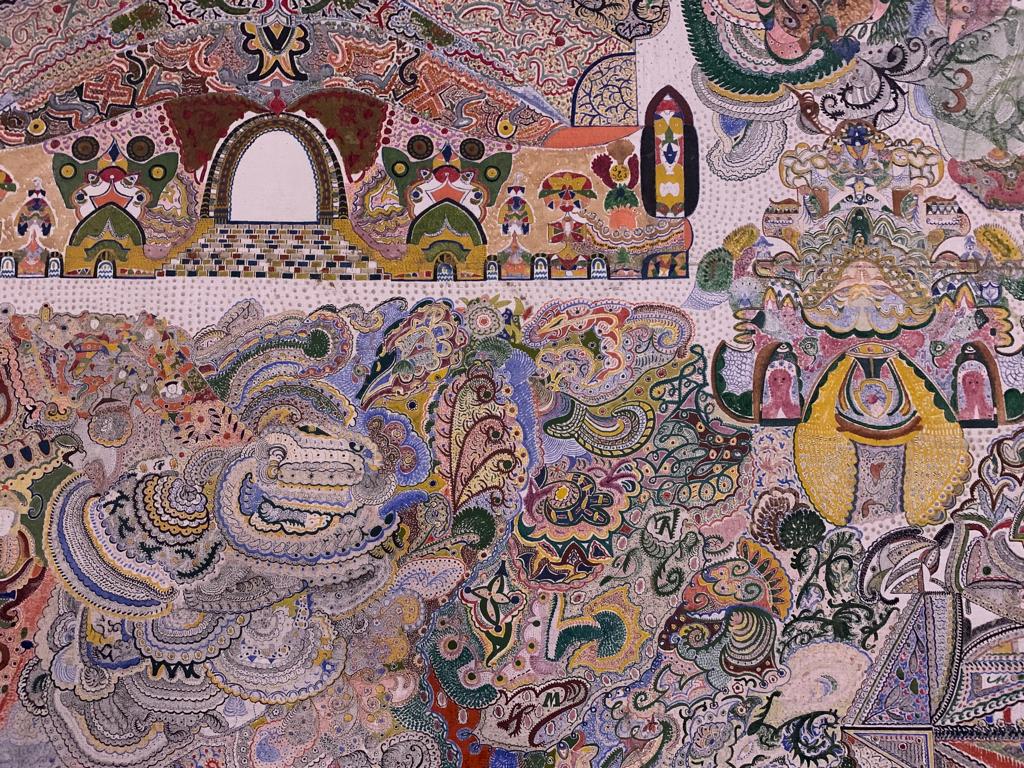

Long-time Salterton Arts Review followers will know I have a particular interest in so-called Outsider Art. More on nomenclature in a moment but let’s call it that for now. Underneath this broad umbrella I’ve seen exhibitions of spiritualist art, art by self-taught artists from the American South, and more. Some artists who are/were on the inside of the art world rather than the outside overlap with this category, either because they drew inspiration from outsider art sources, or created art to reflect an idiosyncratic inner world in much the way an ‘outsider artist’ might (like this example).

Perhaps the best-known artist to have taken inspiration from ‘Outsider Art’ was Jean Dubuffet. We saw a large-scale retrospective of his work in 2021 at the Barbican. Dubuffet was not a Lausanne or even Swiss native: he was born in Le Havre, France, in 1901. He studied art in a conventional way as a young man, but moved away from it before again picking up his brushes in 1942. Dubuffet had always followed his own path, drawing inspiration from unconventional artists such as Jean Fautrier. He flirted with Fauvism and Surrealism before settling on a style he would name art brut (‘raw’ art). Over the years he built up a personal collection of art brut: works spanning cultures and borders produced by self-taught artists, artists undergoing psychiatric treatment – basically anyone outside the artistic mainstream. For Dubuffet, this art was more real, more human, than art in the academic painterly tradition.

From the early 1970s, with more than 5,000 pieces in his collection, Dubuffet began to think about its longevity. He was refused a special collection status in Paris, and rejected offers from regional authorities to house his collection. In the end he turned to the city of Lausanne. Today, the Collection de l’Art Brut is housed in the 18th Century Château de Beaulieu, whose renovation Dubuffet partly funded. It has continued to grow since the 1970s, and now numbers over 70,000 works, approximately 700 of which are on display.

Displaying Art Brut

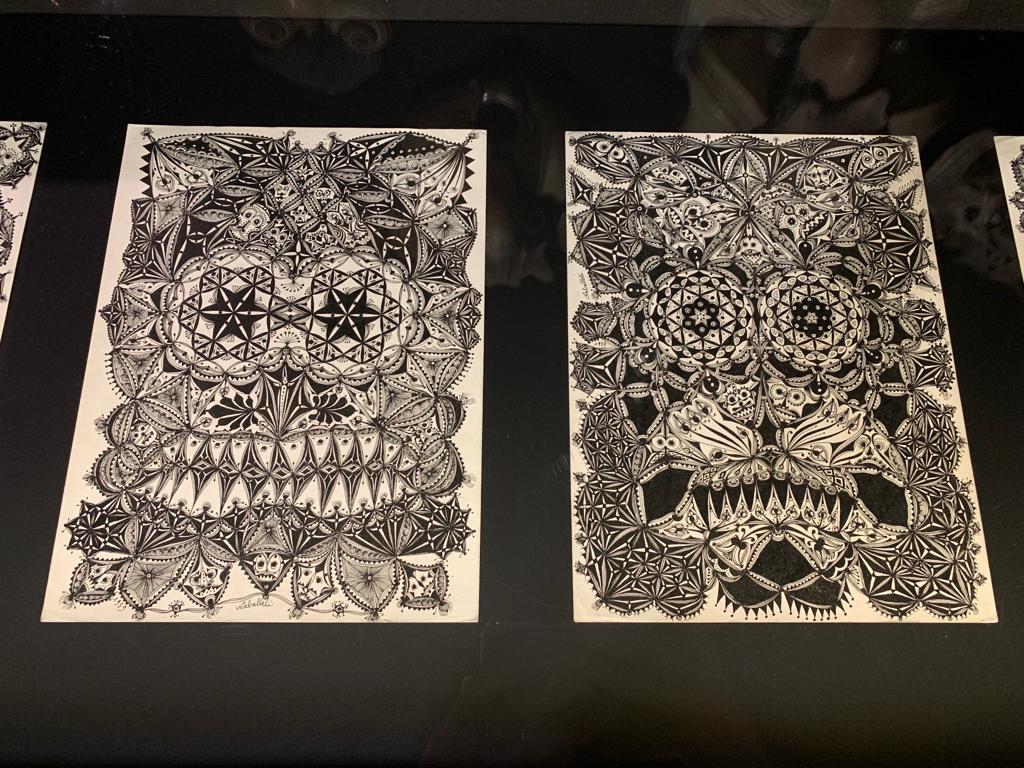

The first thing a visitor may notice when entering the Collection de l’Art Brut are its black walls. This is a deliberate choice, in place since the museum opened in 1976. It’s the opposite of the ‘white cube’ convention of plain white walls which emerged at about the same time. The black walls are designed to be anarchic, subverting expectations and encouraging contemplation. The effect is like a cave, taking visitors out of the day to day.

The museum is fairly large. The majority of the permanent collection displays are in a converted barn, with connected exhibition spaces. As you would expect, unconventional artists do not always adhere to conventions of size and format, so the space is flexible enough to accommodate very long or wide works as well as assigning smaller spaces to more immersive oeuvres.

There are works here crossing painting, sculpture, drawing, found object assemblages, and more. As much as the artworks themselves, however, it’s the artists’ biographies which are important. What is it that puts each of these artists outside the cultural mainstream and merited their inclusion in the collection? So groupings of works by the same artist are found together with a biographical panel explaining their life and work, including a photograph where possible. It makes for a lot of reading but it’s very interesting.

You can see an evolution in the collection by reading these panels. Dubuffet’s own collecting reflected contemporary interests and focused heavily on art by people undergoing treatment for mental health conditions. Post-Dubuffet, there’s evidence of more artists, from Europe and further afield, who are simply self-taught but with a strong creative instinct which led them to pursue art perhaps later in life. An icon on the panels indicates which were part of Dubuffet’s original collection.

What Is Art Brut?

We’re going to circle back now to one of my favourite topics: thinking about terminology for art of this kind. I’ve discussed this on the blog a couple of times before, but it’s tricky enough that I haven’t yet come to a firm conclusion.

What’s the problem? Well, there are no terms in this space that I’m fully comfortable with. ‘Outsider Art’ ensures some artists remain on the outside (although some artists in this collection command high prices these days). ‘Naive Art’ is patronising. ‘Art brut’ feels uncomfortable if directly translated as ‘raw art’. ‘Self-taught artist’ isn’t always entirely true, as we discovered in this exhibition. I don’t like this phrase from Lausanne’s tourism website: “visitors come to reflect on and understand these artists who are not artists.” I prefer this one from the Gallery of Everything: “artists and makers beyond the cultural mainstream.”

Really, for me, what it boils down to is gatekeeping. Why does Lausanne say that these artists are not artists? Who decides that some artists are on the inside and others are on the outside? Many of the artists represented here made art primarily for themselves but others, such as Madge Gill, worked and exhibited as artists. All of the available terms ‘other’ the artists and pass judgement on what real art is, even when lauding their accomplishments.

It’s for this reason that I quite like that phrase: artists beyond the cultural mainstream. Avant-garde artists could also be considered beyond the cultural mainstream. Thinking about it in terms of being inside/outside a mainstream is far more inclusive than being inside/outside art itself. I’m sure this will be an ongoing internal debate, but for now that’s where I am.

Final Thoughts On The Collection De L’Art Brut

Final, that is, except for two quick sections below on temporary exhibitions I saw there in July 2023.

Having such a personal interest in art outside the cultural mainstream, I am very pleased to have had the opportunity to see this museum. It’s a fantastic collection with real depth in terms of the number of artists represented and the works representing them. The personal nature of the original collection means European artists are very heavily represented, but more recent collecting has evidently tried to address this.

The museum’s temporary exhibition programming puts it in dialogue with the wider art world. Of the two exhibitions I saw, one bridged the gap between ‘Outsider Artists’ and the wider human creative instinct. The other was by a contemporary artist whose work shares qualities of directness and unbridled creativity with some of the artists in the collection.

Overall, this is an excellent museum experience and should be on the list of any culture-loving visitor to Lausanne. The Collection de l’Art Brut is a case study in many things. How to grow a personal collection beyond its original owner. How to display art sensitively and with the right level of background information. Or there’s how to use temporary programming to bring a broader focus to a narrow collection. And even how to convert a historic space into a modern, welcoming museum. Whatever your motivations, it’s worth a look.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Photomachinées

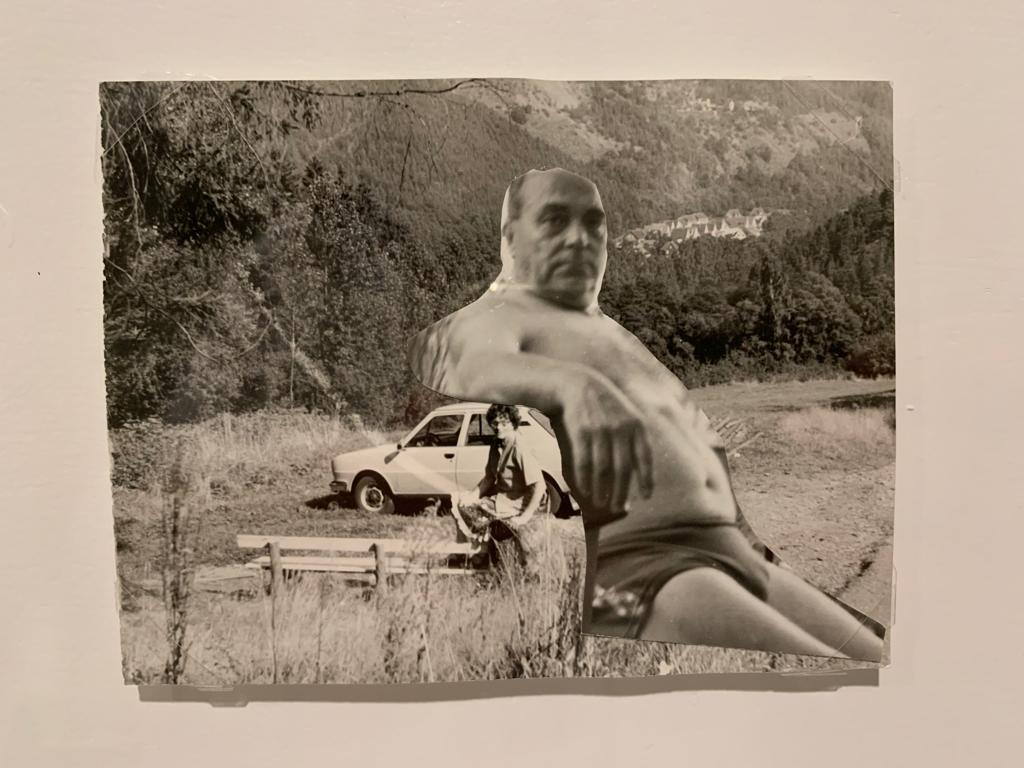

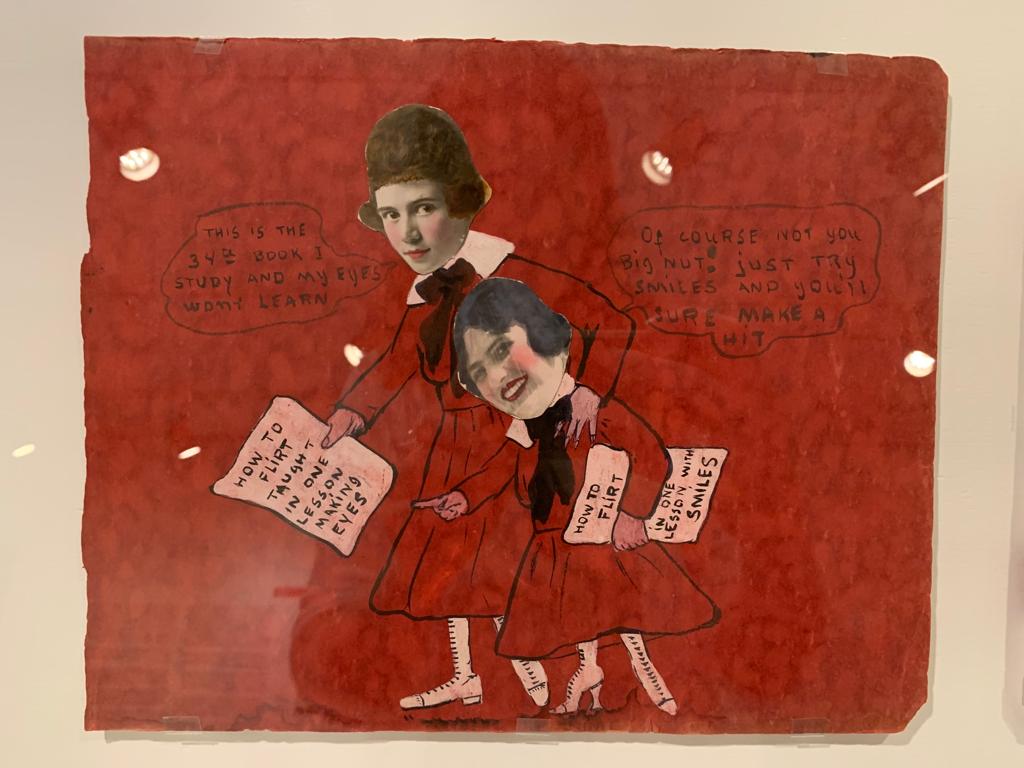

The name of this exhibition doesn’t translate too well, but suggests photos that have been manipulated in some way. Spread across two galleries in the Collection de l’Art Brut, it’s a collection of photographs sourced from flea markets and junk shops by two collectors. Antoine Gentil and Lucas Reitalov donated their collection to the museum in 2021.

The resulting photographs are grouped by the type of intervention. Recompositions. Mergers. Funny collages or doodles. Painted photographs. Even manually-constructed panoramas. There are photos missing a heart-shaped section cut out for a locket. Photos where someone has fallen out of favour and been literally scratched out.

The perspective is interesting. An object undergoing human intervention can become an artwork even if that is not the intention. By grouping them, we can see the same impulses occurring by multiple anonymous hands. The simple fact of deliberately collecting things and bringing them into the gallery is sometimes enough to transform them into ‘art’. It brings to mind Ai Weiwei buying up hundreds of neolithic hand tools as seen here.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Photomachinées on until 24 September 2023

Michel Nedjar

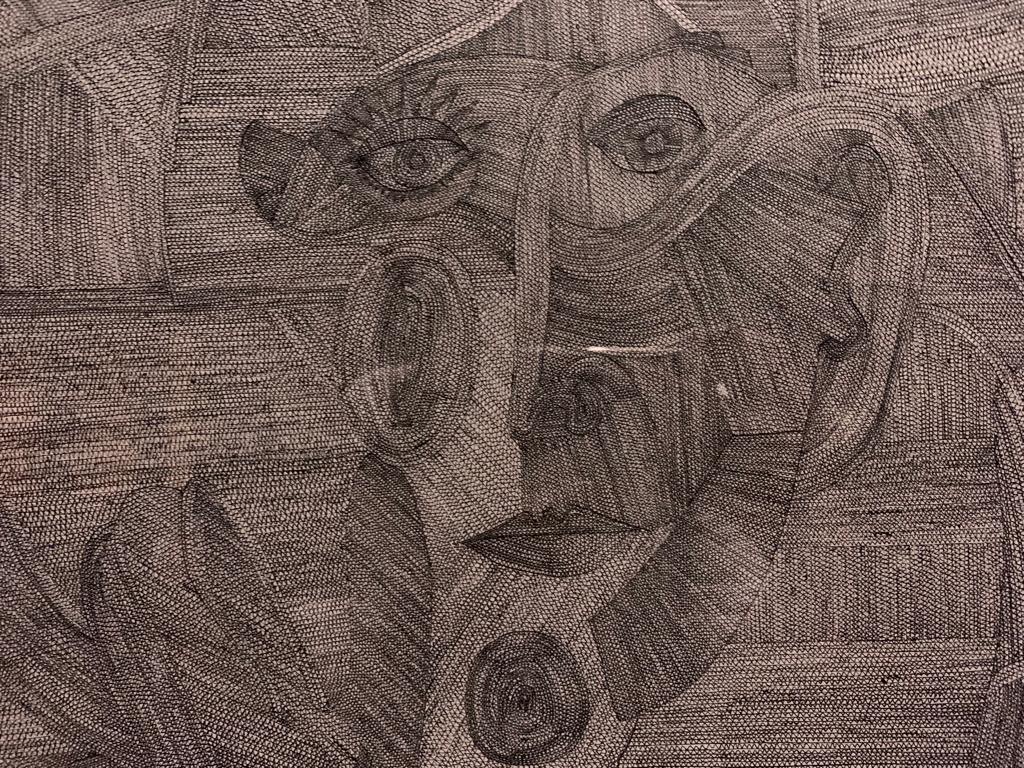

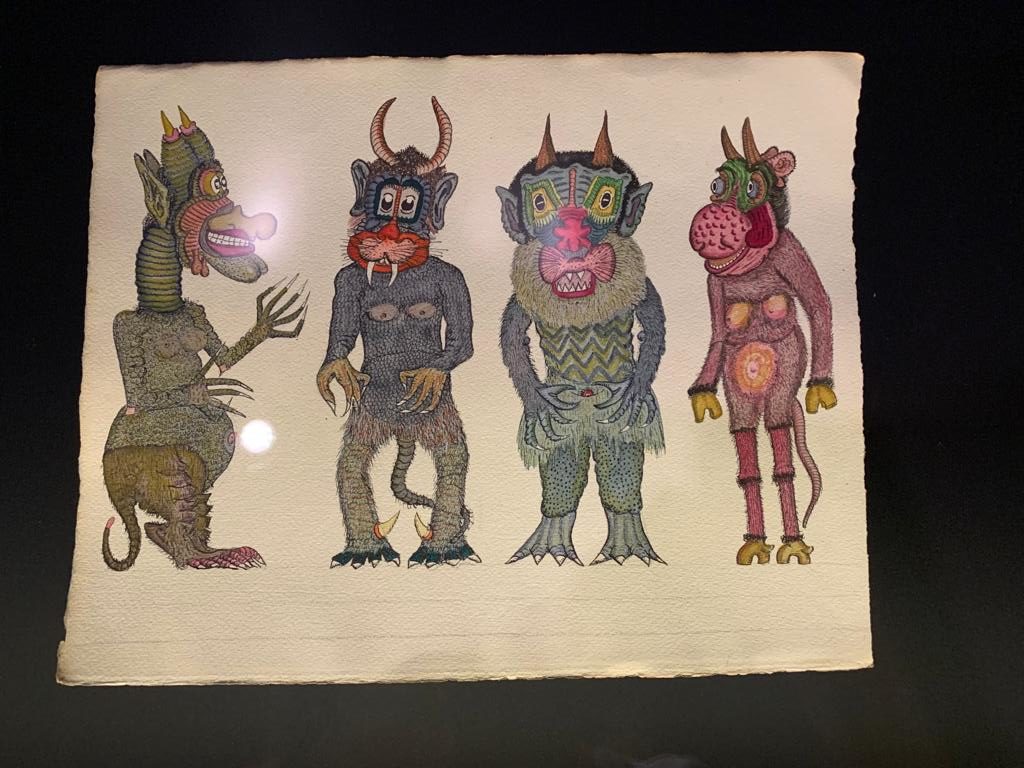

Michel Nedjar is a French artist born in 1947 to a Jewish family with Algerian and Polish roots. He is also a perfect example of why some of the terms for art outside the mainstream are too restrictive. Art brut was the beginning of his journey. It was after seeing a reproduction of a work by Aloïse Corbaz that he decided to become an artist, without formal training. He has produced numerous series of artworks over the years, often naming them with newly-coined terms such as ‘Chairdâmes’ and ‘Animo’ – French wordplay.

Many of the works in the exhibition – the first monographic one for Nedjar – come from the Collection de l’Art Brut’s holdings. But Nedjar’s works are part of museum collections worldwide (hence not an ‘Outsider Artist’ in that sense). I spotted several loans from familiar institutions. The works on display give a sense of Nedjar’s multidisciplinary, idiosyncratic approach. Works in fabric, particularly dolls, feature heavily. Faces are a related motif, peering out from works on paper and collages. Experimental films give further insights into the artist’s approach and world view.

Is Nedjar still outside the artistic mainstream, or is he simply a contemporary artist who didn’t go to art school? An interesting question to pose to oneself as you peruse this well-curated exhibition.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Michel Nedjar on until 29 October 2023

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.