Musée Cantonal Des Beaux-Arts (Cantonal Museum Of Fine Arts), Lausanne

A brand new museum in a new arts district in Lausanne, the Musée Cantonal Des Beaux-Arts takes a walk through Swiss art history.

Plateforme 10

My recent visit to Lausanne was my first. Had I been there on previous trips to Switzerland, I would have missed out on seeing a brand new cultural district in the city. Opening fully in 2022, Plateforme 10 has, as the name suggests, a railway connection. It’s right next to Lausanne’s main station, on the site of a former locomotive repair shed. It houses the Cantonal Museum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts (MUDAC), Cantonal Museum for Photography (Photo Elysée), and the subject of today’s post, the Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts (MCBA). A canton is of course a Swiss member state, and there are 26 of them. Lausanne is in the canton of Vaud.

My research indicates this new arts district has been a while in the making (since 1991). Back in 2008, a vote to move the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts to a site on Lake Geneva was refused – in Switzerland a lot of things are put to a popular vote. They take their democracy seriously. So some 15 years later, here it is, in a new location with some cultural friends to keep it company.

The designs of all three museums, or rather the two museum buildings (MUDAC and Photo Elysée are in a clever shared space), are modern but stark from the outside. There’s also been a lot of deliberate retention of the industrial, railway feel: gravel walkways, little decoration, etc. The result is an imposing but barren-feeling arts hub. In the summer it’s pleasant enough, but in the winter I imagine it must verge on bleak.

It is in any case an interesting project: how to transpose historic collections into entirely new spaces and a dialogue with each other. I was short on time so visited only one of the three. Let’s take a look at it now before regrouping for some final thoughts on Plateforme 10.

Le Musée Cantonal Des Beaux-Arts

This is far from the first time the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts has found itself in a new home. A cantonal museum had been developing for some time, but the first real Musée des Beaux-Arts opened in 1841 as the Musée Arlaud. The architect was Louis Wenger who also designed what is now the Fondation de l’Hermitage. The Musée Arlaud was comprised of two significant private collections, with more added in later years. There was also a 19th Century focus on collecting Swiss contemporary (for the time) art.

A second new site, the Palais de Rumine, opened in 1906, with the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts occupying a section. Further private collections represented major increases to the collection, as did some serious acquisition policies. The museum was also outward-looking: under the direction of René Berger between the 1960s and 80s the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts entered into a sort of artistic exchange programme with museums around the world to showcase developments in contemporary art.

After the local authorities took a decision to move the museum into its own building all the way back in 1991, decision-making within the museum followed accordingly. Director Jörg Zutter made ambitious acquisitions and balanced programming between local and international artists. Yves Aupetitallot, Director between 2001-2006, looked back at the museum’s past for inspiration. Bernard Fibicher then saw the museum through from 2007 to its new home which opened in 2019.

Exploring The Museum

The current building is by Spanish architects Barozzi Veiga. It’s a big rectangular building with brick fins, but no other breaks in the façade other than a small outline of the former locomotive shed and the entrance. Through the entrance, visitors discover a large foyer dominated by a sculpture in the form of a tree which draws the eye upwards to appreciate the space’s full height. I visited on the first Saturday of the month when cantonal museums are free, but the lady at the small ticket window still provided me a sticker and reminded me I could visit the other museums too. All three can always be visited on the same ticket.

Once inside, there’s a very logical order to things. One side of the building houses the permanent collection, the other temporary exhibitions. With a small exception, but the point stands. In between are stark concrete staircases, sometimes with seating and views over the railway tracks. The exhibition when I visited was Magdalena Abakanowicz, which I had already seen at the Tate, so I mostly stuck to the permanent collection side. Mostly – a bit more on this later.

The move to Plateforme 10 seems to have come with some big decisions. For instance, the museum’s Wikipedia page hints at a much larger collection than what I saw. I don’t mean in number, as all museums have most of their things in storage. But I had no hints that the collection covers art from Ancient Egypt to today. And in fact a leaflet I picked up at the museum gives the same number of 10,000 objects, but puts the date range as the second half of the 18th Century to today. Wikipedia misinformation, or has there been deaccessioning or repartitioning between museums going on? I would think the latter, if anything.

A Journey Through Swiss Art

My experience of the Musée Cantonal Des Beaux-Arts very much matched the latter description rather than the former: art from the 18th Century to today. The permanent collection is exhibited over two floors, and reminded me of my visit to the National Museum of Iceland last year in that you go along the first floor one way, up the stairs, and back the other way. Again a model of efficiency: dare I say something about a Swiss watch?

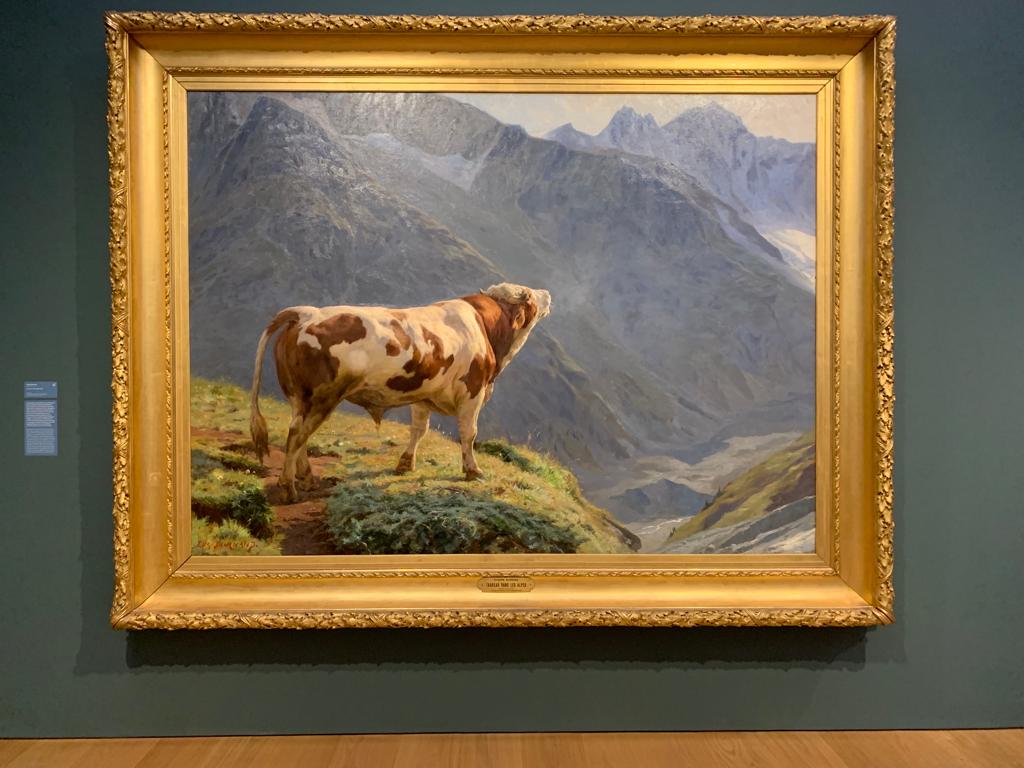

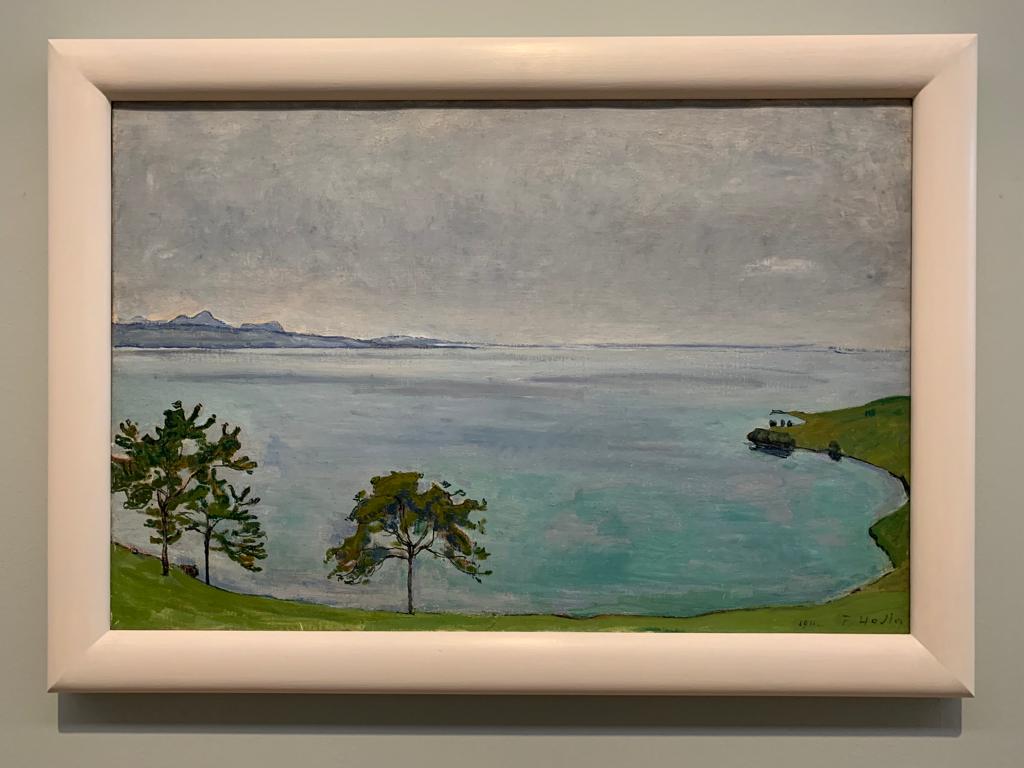

Over these two floors the art is mostly, but not wholly, Swiss. It starts on a rather violent note with a 16th Century work by François Dubois, a Huguenot refugee reliving the trauma of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in paint. Generally things are a lot more sedate, in line with Swiss history: mountains, lakes, the odd cow. There are formal portraits and serene landscapes. Early experimentation comes in the form of Charles Gleyre, inspired by his travels to make sketches of individuals in Egypt and Sudan.

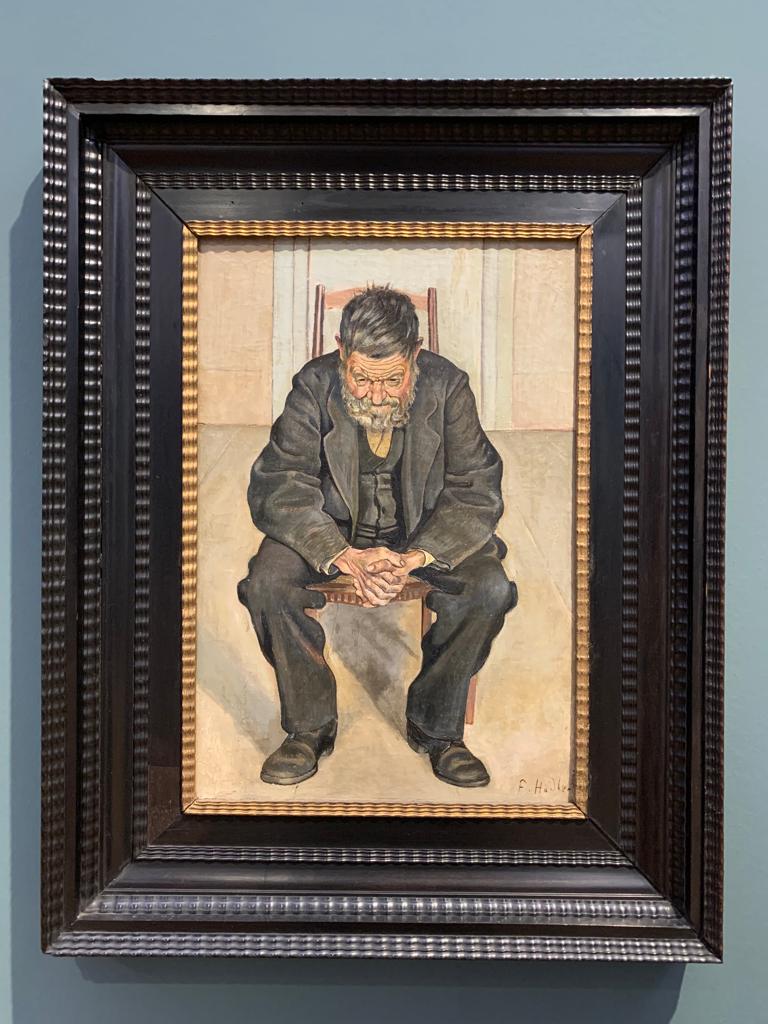

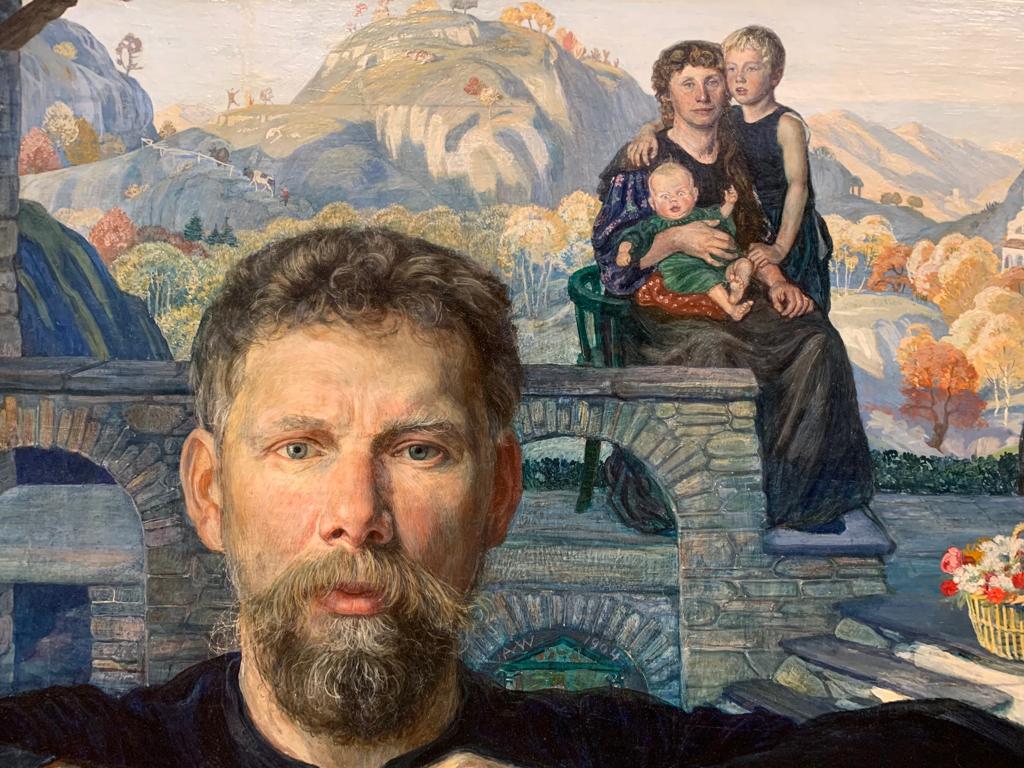

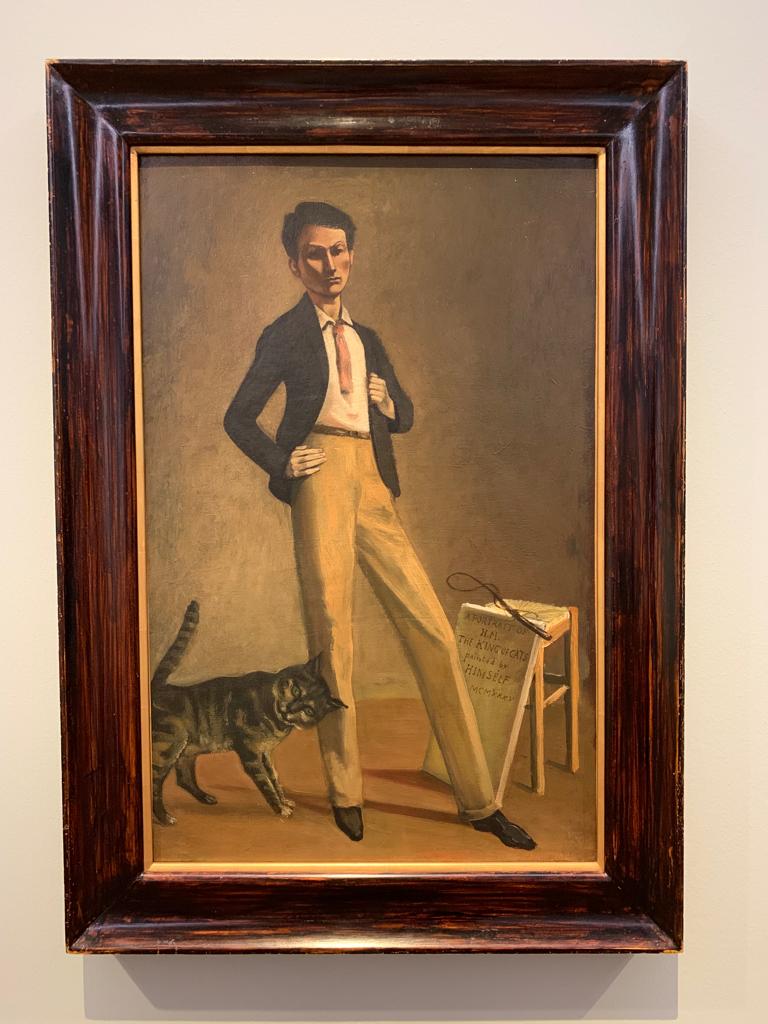

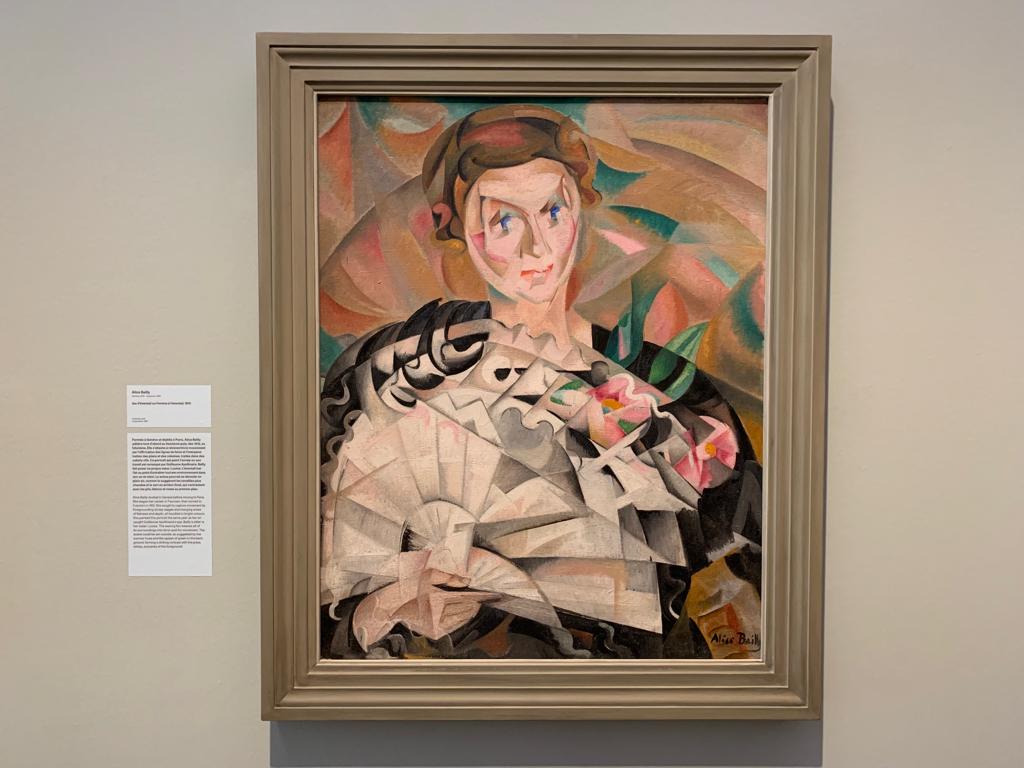

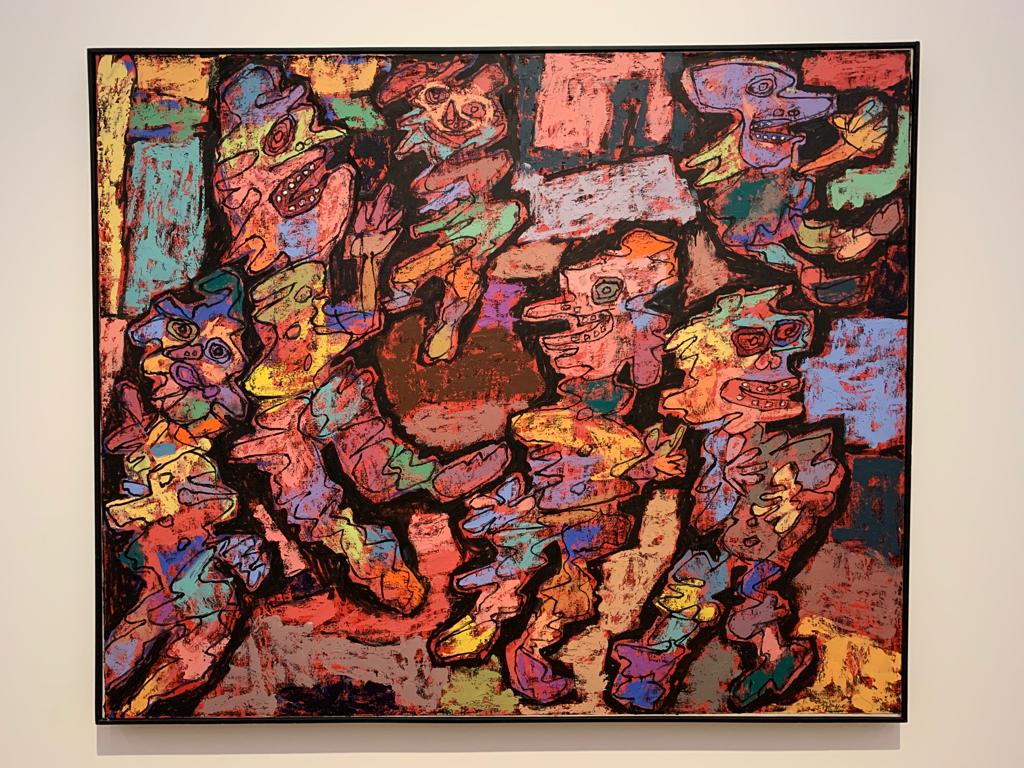

Luckily for me, the period in art that I particularly like is well represented in the collection. I’m talking the likes of Ferdinand Hodler, Félix Vallotton – turn of the last century, a bit of Symbolism, that sort of thing. There are a lot of engaging portraits from this period, often surrounded by original handmade frames which add to their charm. A striking example is Albert Welti’s 1904 Portrait de famille (Family Portrait). The artist stares out of the frame, his wife and children in the middle distance. His direct gaze challenges us, shows off the intricate realism of his skill in tempera. It stays in my mind as I walk through a final room on this floor with modern works: Dubuffet, Giacometti, Balthus and Alice Bailly.

And Into Contemporary Art

Heading back along the upper floor (after a brief interlude in which I saw a temporary exhibition harking back to the days of intercultural artistic exchange), things become less Swiss and more international. Experiments with the form or size of canvases. Replacing canvases with objects. The scribblings of Cy Twombly. A work or two by William Kentridge. A canvas whose entire decoration is rose thorns.

This floor takes us from the 1950s to the present day. Frankly I missed the local focus as Swiss names gave way to international ones represented in museums the world over. Knowing what I do about the museum’s history, however, I see it for what it is: a statement of intent. Some will be later acquisitions, but these rooms were part of a choice to look outwards in the mid-20th Century. To create links with international artists and movements and bring their works into the galleries. And it’s not that there are no Swiss artists sprinkled in there.

A few highlights stick with me. First and foremost there is Real Pictures (1995-2007) by Alfredo Jaar. A Chilean-born artist, Jaar is deeply engaged in current affairs. This work confronts the Rwandan genocide of 1994. It consists of black boxes, each representing the story of a survivor. Their photograph is within, with only a written description on the cover. The anonymity on even this relatively modern scale is a memorial to the vast numbers of people who lost their lives.

Final Thoughts On The Musée Cantonal Des Beaux-Arts

Not quite the final section though, we’re going to take a quick peek at the Magdalena Abakanowicz exhibition next!

The Musée Cantonal Des Beaux-Arts is a very nice museum indeed. I come at this primarily as a great lover of museums visiting a state of the art example. Its use of space is impressive, the rooms are still crisp, clean and new, and the artworks are hung and mounted beautifully. Given a second day in Lausanne, I would have happily made a day of it and visited the other two institutions in Plateforme 10 as well.

In terms of art, I feel a bit less effusive. There’s nothing wrong with what’s on view, it depends what you’re hoping to get out of it. For me, as a visitor, probably the most interesting thing I can see in a Swiss art museum is Swiss art. I therefore noticed the move away from local artists between floors, and somewhat regretted it. Nonetheless I got to see a lot of nice artworks, including a whole floor which was just what I was after. For locals, of course, a blend between art from here and further afield is important, and this display serves them well.

A good location trumps so much, in any case. For visitors to Lausanne, you could not get a spot more well-placed than Platforme 10 and its three museums. Even if the industrial vibes are a little bare, there’s a lot to see and do here as you arrive in town or before you leave. Having hiked to two museums further up the hill, there’s something to be said for this convenience.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

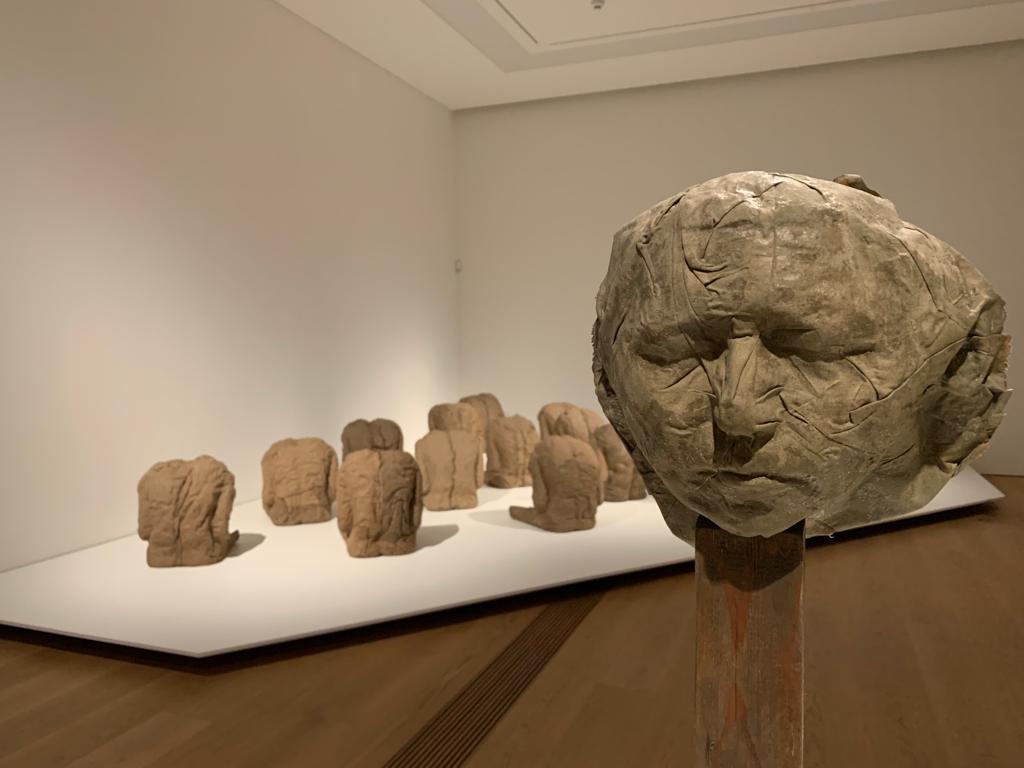

Magdalena Abakanowicz: Textile Territories

I’ve spoken before about exhibition happenstance: the great good fortune when I miss an exhibition in one location and find it in another. It happened to me once in Reykjavik, for instance. What is even less likely is coming across a museum in two locations and being able to see it twice. It comes down to timing, of course. And as a museologist who likes to think about the bottom line, I’m also unlikely to pay for tickets to something I’ve seen already.

On this occasion, I had no such worries. My ticket included the temporary exhibition, so I could pop in on my way out to compare and contrast. And what I found was interesting. This exhibition is a collaboration between four institutions: the Tate, the MCBA, the Fondation Toms Pauli which is actually headquartered in this building, and Henie Onstad in Norway. The Tate and MCBA exhibitions are quite different: I wonder if a Norwegian one would be as well?

Apart from the different titles (Every Tangle of Thread and Rope vs Textile Territories), there are differences in focus. For starters, there’s a second artist here, Elsi Giauque. A Swiss textile artist, her geometric and brightly coloured work could not be more different than Abakanowicz’s. Her inclusion here provides both a contrast and a local connection: another textile innovator closer to home.

It’s interesting to see how one exhibition can have different interpretations in different places. A similarity though is how good an introduction it is to the artist’s work. And how much I want to wrap myself up in one of those big, hanging Abakans.

Magdalena Abakanowicz: Textile Territories on until 24 September 2023

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.