L’Abbaye Royale De Fontevraud (The Royal Abbey of Fontevraud)

Resting place of Plantagenet kings, a prison, a cultural centre: the Royal Abbey of Fontevraud has seen it all!

A Journey To Fontevraud

On a recent visit to France, I got out and about seeing a variety of sights. There was a local street performance festival, and even a day or two of activities relating to troglodytes! It just goes to show, even in a region with famous sights (in this case the Loire Valley), what a range of cultural activities exist.

Just before starting our journey back to London, which began from Saumur train station, we made one final stop. We wanted to see l’Abbaye Royale de Fontevraud (the Royal Abbey of Fontevraud), a site with connections to French and English history. But first a little background on its religious history.

The story begins with Robert of Arbrissel, Archpriest of the Diocese of Rennes. He carried out a reformist agenda in Rennes, and when he was forced out following the death of the bishop in 1095 he turned to life as a hermit. His life of severe penance and his eloquence gained him many followers, to the extent that the influx of monastic converts from all walks of life was too much for the abbey he founded in La Roë and he quit both the office and the community.

Around 1100 he tried again to found a religious community. At first he had men and women living together in his order, but this was frowned upon and they soon separated. Both communities remained under the authority of an Abbess. One of the stipulations in Robert’s Rule of Life for his community was that the Abbess be someone with experience of the world rather than someone who grew up in the Abbey, but this only lasted the first two terms. Other rules were around simple dress and food, silence and good works. The Count of Anjou gave significant property to the Abbey by 1106.

Resting Place Of Plantagenet Kings

By the time Robert died in around 1117, there were at least 3,000 nuns in the community and many priories around France. In subsequent decades this particular abbey at Fontevraud even came to have a royal connection. This wasn’t so unusual at the time: abbesses were often from noble families, and withdrawing to a religious life was not uncommon for royal and noble women (remember Hamlet telling Ophelia to “get thee to a nunnery”?).

The woman in question, who forged this royal connection, was Eleanor of Aquitaine. Her Wikipedia page is worth a read, she had quite the life! Duchess of Aquitaine, Queen of France until she annulled her marriage, Queen of England when her second husband ascended the throne as Henry II, intrigues, imprisonment, Crusades: her story has it all! Henry II was the first of the Plantagenet dynasty in England, or part of the Angevin Empire if you prefer. He and Eleanor fell out big time in later years, mostly over Eleanor supporting their son, also Henry, in a revolt. No surprise that in later life, now a widow, Eleanor was exhausted and chose to take the veil at Fontevraud.

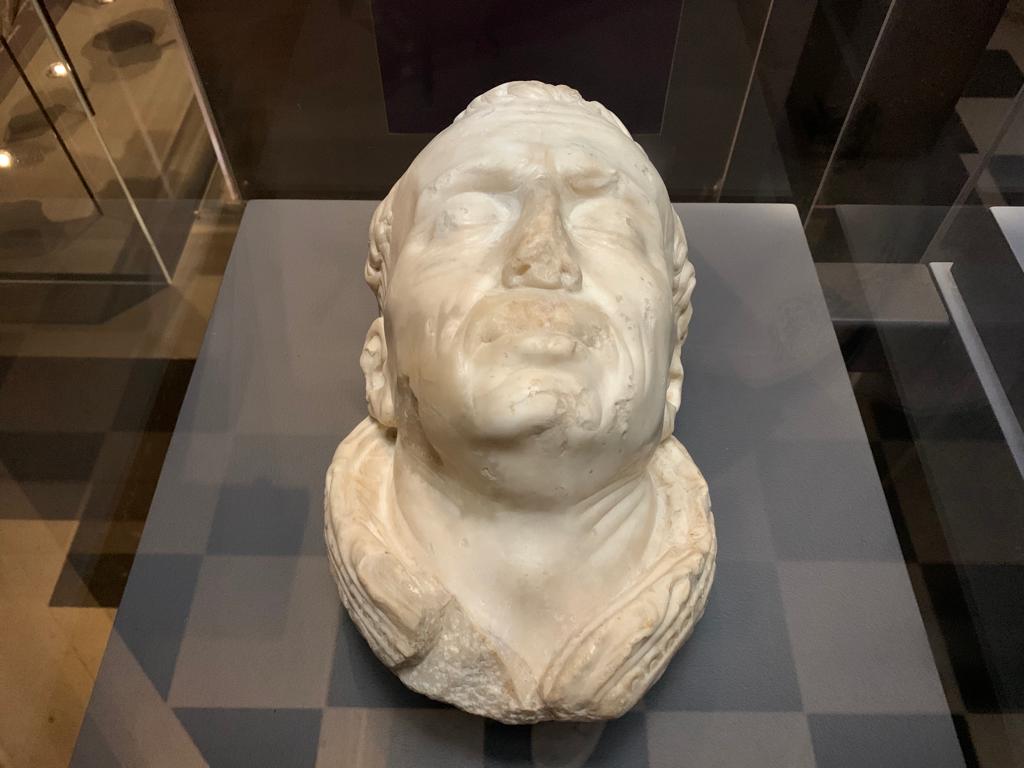

Henry II of England, Eleanor of Aquitaine and their son Richard the Lionheart were all buried in the Abbey of Fontevraud. However, history is rarely, if ever, simple. They managed several centuries of peaceful rest, until the time of the French Revolution. Its anti-royal and anti-religious sentiment made places like Fontevraud prime targets. The bones of Henry, Eleanor, Richard and other notable personages were dispersed and permanently lost. (As a side note, not all of Richard was buried at Fontevraud and his heart can be found at Rouen). Thankfully their rare effigies survive and can be visited today in the Abbey church.

And Then A Prison?

By the time of the French Revolution in 1789, the monastic order based at Fontevraud was already much reduced. Nonetheless, around 200 nuns and a handful of monks held out until the very end, circa 1792, before they were finally evicted. All property of the Catholic church had become property of the nation, including fine abbeys like Fontevraud. Some churches became things like ‘Temples of Reason’, while other church buildings were put to a more practical use. The Abbey of Fontevraud was in the latter camp, and became a prison in 1804. This necessitated a lot of changes and extensions to the buildings. Some of the artworks survived surprisingly well. For instance judgements on prison rule infringements took place in the former chapter house, watched over by a cycle of paintings on the life of Christ. Apt, perhaps.

Originally intended for around 1,000 prisoners, Fontevraud eventually held about double that. It had a reputation for being one of the toughest prisons in France (after Clairvaux, also a former abbey). Political prisoners experienced harsh conditions at Fontevraud, and it was also the site of executions of French Resistance prisoners under the Vichy government. Fontevraud ceased to be a prison in 1963, when the site became the property of the French Ministry of Culture. A major renovation programme took place to convert it back to its more historic aspect. It opened to the public in 1985.

Today many visitors come to the village of Fontevraud (which has always made a living from the abbey one way or another) to see this complex and interesting history. The renovation project is complete as of 2006, and the focus is more on the royal abbey than the prison years. Nevertheless there is plenty to see and experience.

Visiting L’Abbaye Royale De Fontevraud

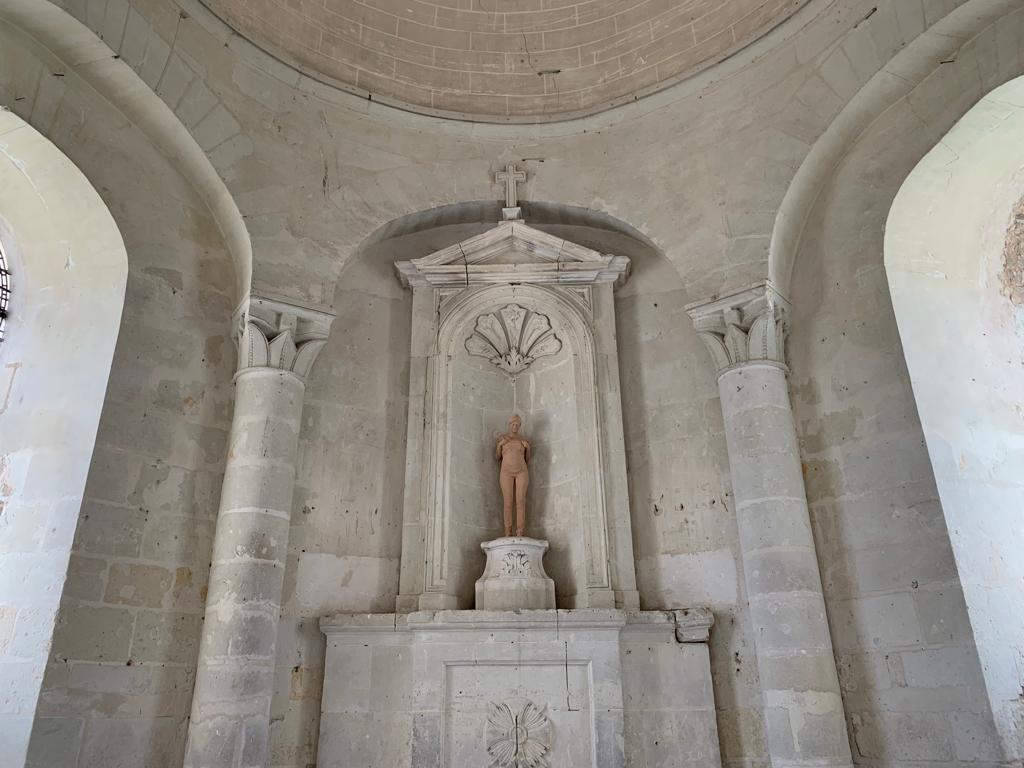

Visitors to Fontevraud today walk through the pleasant village and through a courtyard to reach the abbey. First stop is a ticket office, and then a short path down to the abbey church. For many (including us) this is the main event. Although the Plantagenets are no longer here (see above), there frankly isn’t much difference between seeing an effigy for a now missing body, and seeing an effigy with bones hidden underneath. Something of Eleanor’s education and worldliness comes across, as she eternally reads a bible in her fine jewellery. And seeing Richard the Lionheart’s effigy is a small pilgrimage moment for many an English visitor, I’m sure. For art and history geeks, it’s impressive how much of the polychrome decoration survives.

From the abbey church it’s pretty much a free range visit. You emerge from the church into cloisters, and can wander around looking at the chapter house, dormitories, refectory: all the usual monastic features. There is a one room museum which features objects relating to Fontevraud’s religious history. Portraits of abbesses, religious sculptures, that sort of thing. Later on, you can learn more about the history of Fontevraud as a prison in another dedicated museum space. Then you exit the complex into the abbey’s spacious garden.

So far, so normal (with the possible exception of the prison history). There are a couple of unusual features which were a little less expected. One of these is up in the roof space. This was once dormitories, as evidenced by a little peep hole for the nuns to watch church services below. It now houses an exhibition about the creation of a set of contemporary bells for the abbey. It’s fascinating observing the combination of traditional techniques with modern sensibilities. And on the way out you can walk over the reinforced arches of the church below, something I’ve only ever done before on a tour of Gloucester Cathedral.

Reflecting On Layers Of History

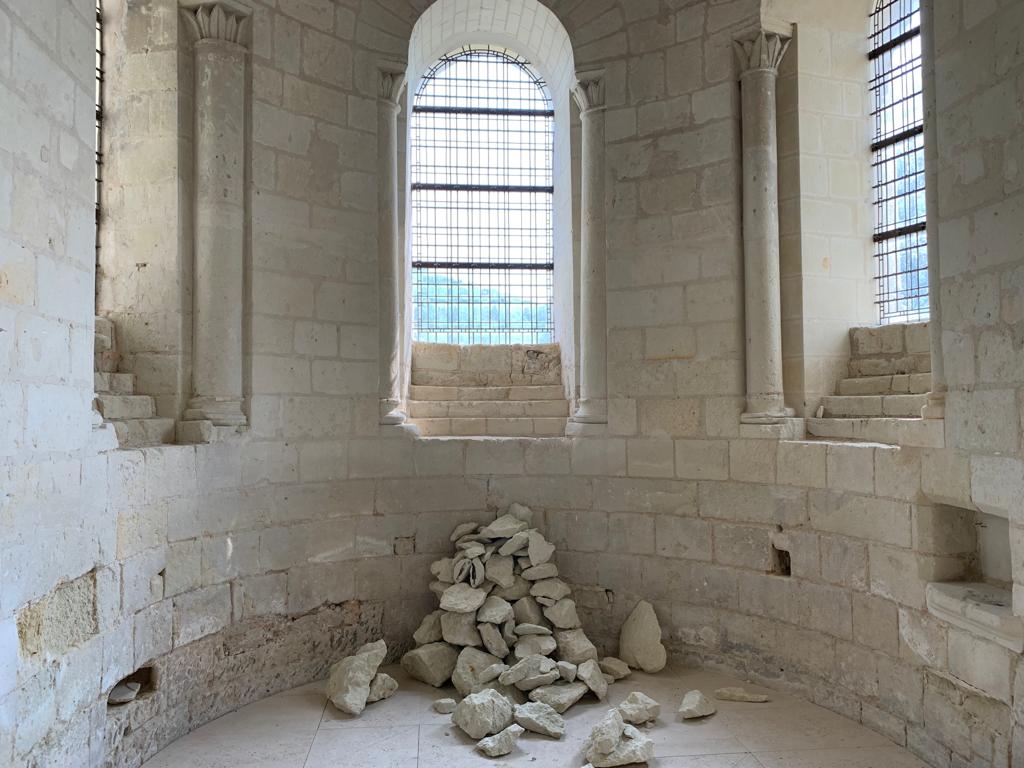

Fontevraud’s history makes it a very interesting site. The choice to bring it back to its appearance as an abbey means a blending of old and new: heavy restoration of the abbey church for instance, which leaves it feeling surprisingly fresh and clean. The occasional leftover from its prison days is an incongruous reminder of how it has changed and changed again.

What really helps in the imaginative work of placing yourself back in the medieval period is the setting. Even today, Fontevraud is surrounded on one site by the town, but on the other side by beautiful open space. Trees stretch over gently rolling hills, and remind you why the abbey is here. Location was important to monastic orders: access to water and resources like timber helped communities to be as self-sustaining as possible. It’s much more in-keeping with a quiet, contemplative life than one of hard labour and punishment.

As a historian, I find Fontevraud an interesting case study in how a place tells a story. There are so many stories to tell here. The development of monastic orders in the medieval period. The connection between those orders and noble or royal families. Growth and decline in line with external forces in society. The abrupt end to a way of life after the French Revolution. Increasingly codified and controlled ways of meting out punishment. How we value historic places in different periods. It’s all there if you look for it, just needing a little interpretation to bring it back to life.

Final Thoughts

The Royal Abbey of Fontevraud is a pleasant visit for a couple of hours, up to a half day if you’re thorough. I would have liked to have spent a bit longer there as the town itself seemed rather charming, but unfortunately we had that train to catch back to London.

You probably have to have some interest in history to get a lot out of it, but after that point you can come at it from different angles according to your interests. The interpretation is interesting, even as the abbey’s history renders some of the sights a little bare. And whether or not you’re interested in history make sure you take a trip over to the ‘kitchen’. You’ll notice it as soon as you enter, and in my photos above. It’s the oddly shaped one, more or less circular with little turret sticking up all over. I say ‘kitchen’ in inverted commas because that’s what it’s described as and supposed to be, but it’s unlike any other historic kitchen I’ve seen before. It just goes to show we don’t know everything.

I hope you’ve learned a little something from this summary of my trip to Fontevraud. And if you do visit, I hope you enjoy it! I was very pleased to have seen it as the final stop on this Loire Valley trip: another piece in the puzzle of a region with a lot of interesting history and sights to see.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.