Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine – Hayward Gallery, London

This slow and thoughtful exhibition at the Hayward Gallery shows off photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto’s work to perfection.

Hiroshi Sugimoto

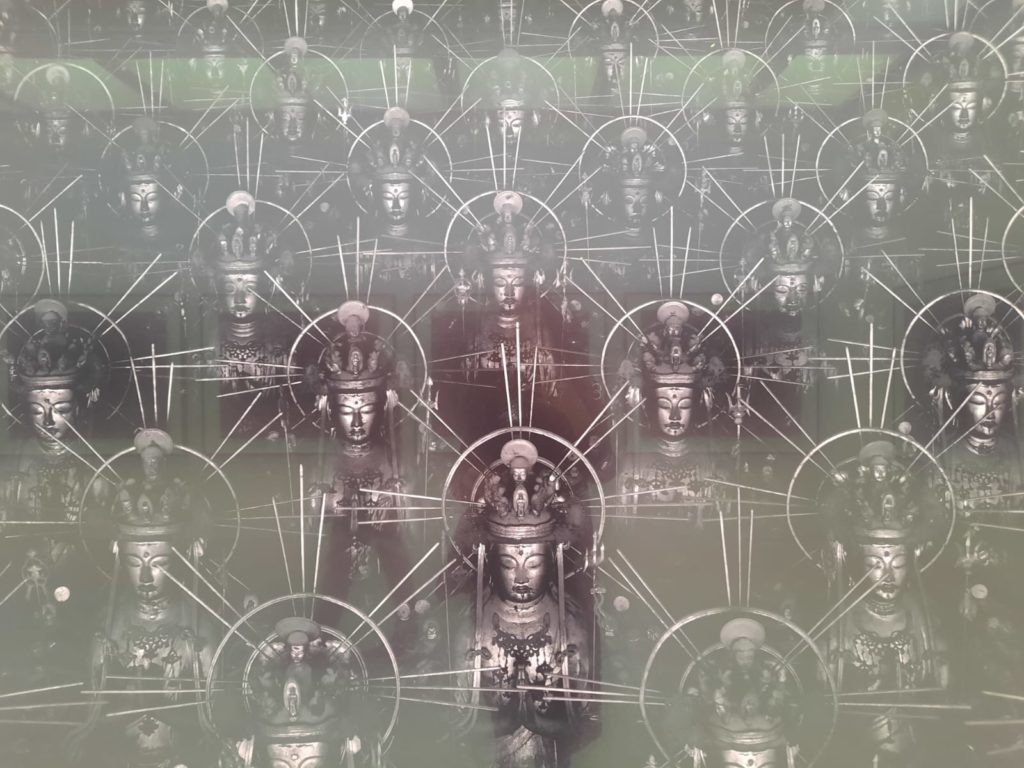

To get to know the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto is to get to know photography itself. That is the impression I had after seeing this survey, the artist’s largest to date, at the Hayward Gallery in London. Sugimoto is a very thoughtful photographer. His work is deliberately slow, and encourages close examination. His interest in photographic techniques, mathematics and optics leads to works that are as fascinating as they are beautiful. In each series making up this exhibition, Sugimoto pushes the boundaries of what a photograph can capture.

Hiroshi Sugimoto was born in 1948 in Tokyo. He showed an interest in photography as a teenager, but first studied politics and sociology at university in Japan before retraining as an artist in 1974 in Pasadena, California. He is also an architect, leading the Tokyo-based New Material Research Laboratory. Since then he has divided his time between Japan and New York City.

Before embarking on a career as a professional artist, Sugimoto worked as a dealer of Japanese antiquities in SoHo, New York. It was in New York that he began the earliest of the series on view here, Dioramas, in 1976. Sugimoto was inspired to photograph the displays of taxidermied animals at the American Museum of Natural History. Through careful framing and lighting and on beautiful silver gelatin prints, he aimed to bring the animals ‘back to life’. Several works from the series are on display here, and they certainly encourage discussion. It’s easy to understand that a photograph of an early hominid couple does not depict reality. But when it comes to the taxidermied animals it’s a little harder to push back on your brain telling you that photographs are of real things, until you take the time to really look and understand the scene in front of you.

Moments In Time

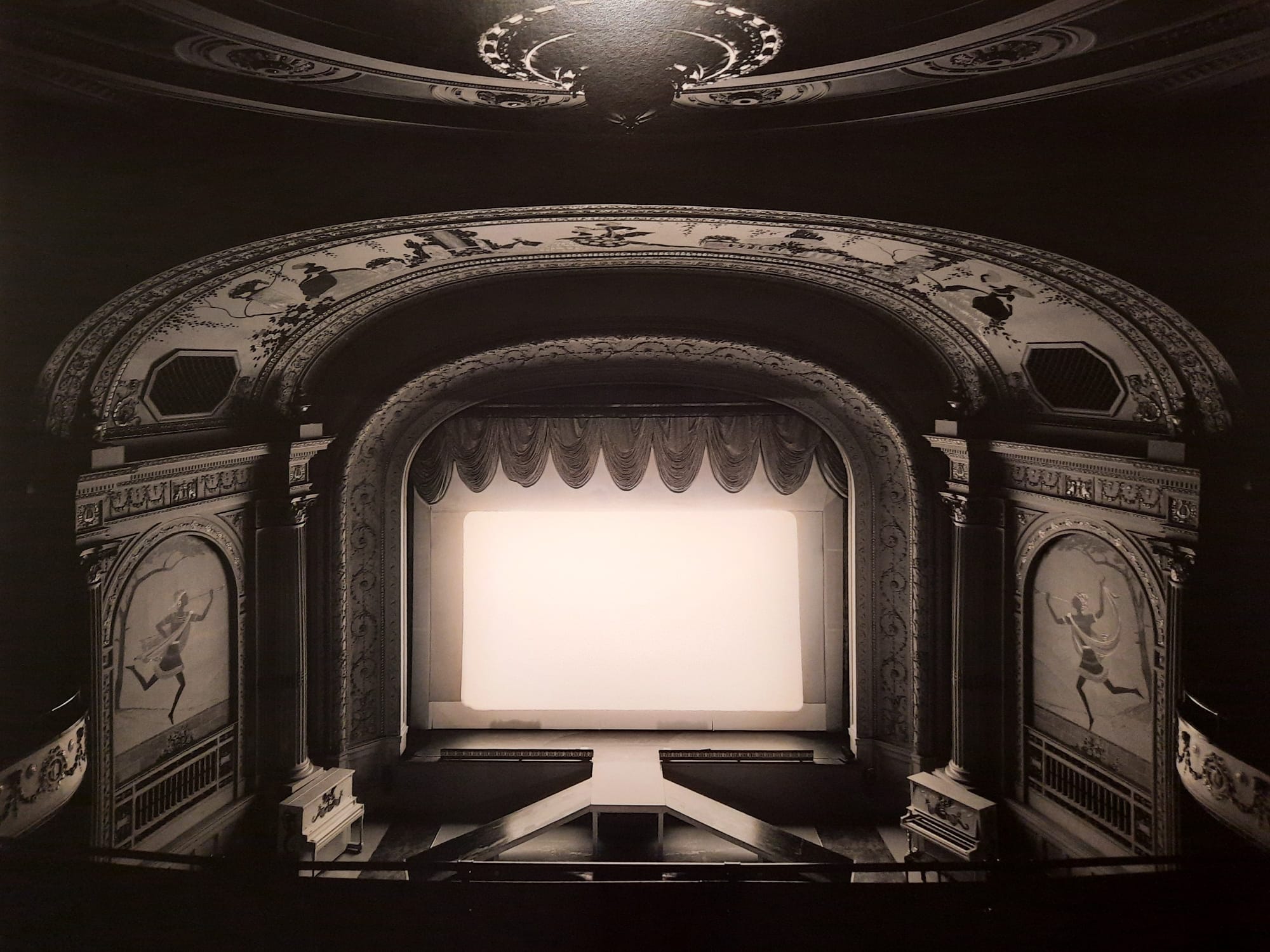

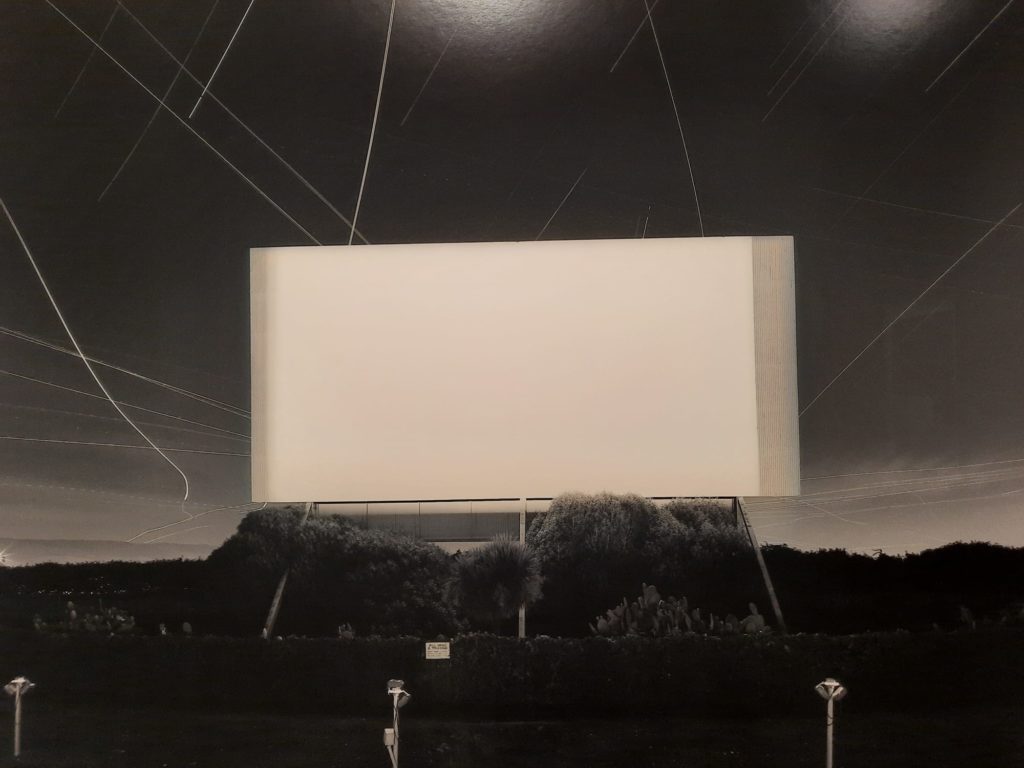

This brings me on to one of the most interesting aspects of Sugimoto’s work: the idea of photography capturing time. Sugimoto favours big wooden camera rigs which taken photographs very slowly. The next series on view, Theaters, features images shot over the entire duration of a film. Historic theatres, drive in cinemas and theatres in ruins are the subject of this series, each with a glowing screen at its centre. Through this ultra-long exposure every frame in a film combines into pure light. It’s a beautiful premise and results in very peaceful works.

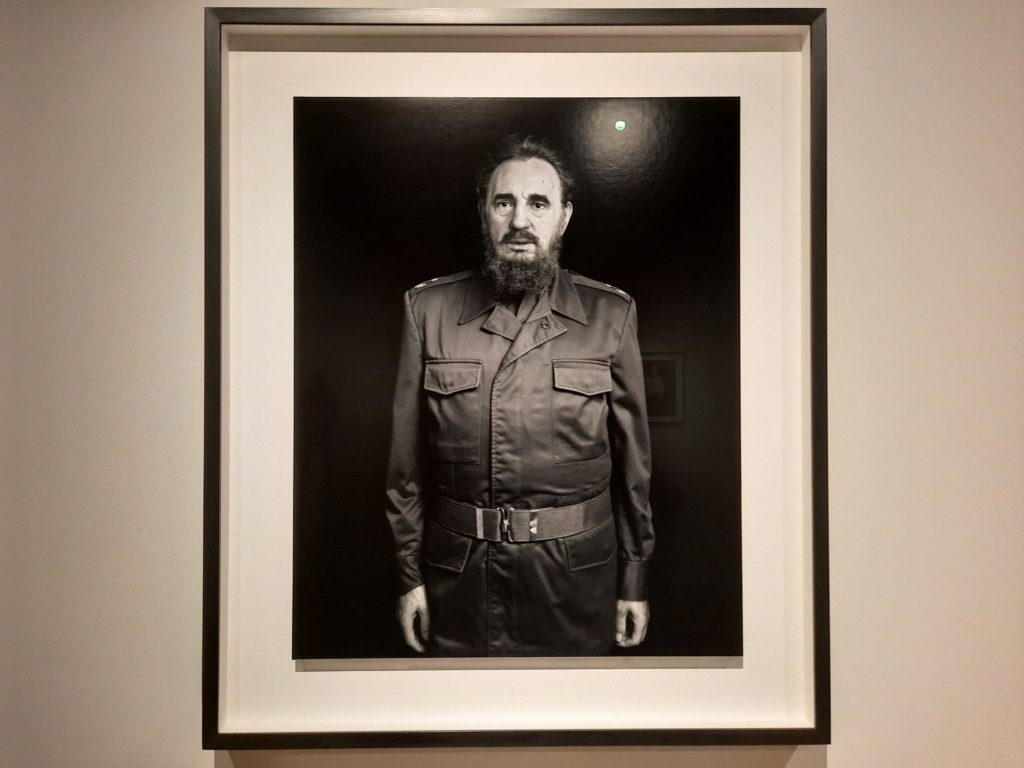

This relationship to time reappears again and again in Sugimoto’s work. The transience of life. The passage of time. The ability of photography to bring scenes, animals or people back to us and create a connection with the here and now. Some of his images are created over the course of hours. Others, like the series Lightning Fields, are the work of an instant, electricity seared into unexposed film. This last is a subversion of a frustration: the annoyance at static electricity destroying an image before it can be fixed changed into creative process within the artist’s control.

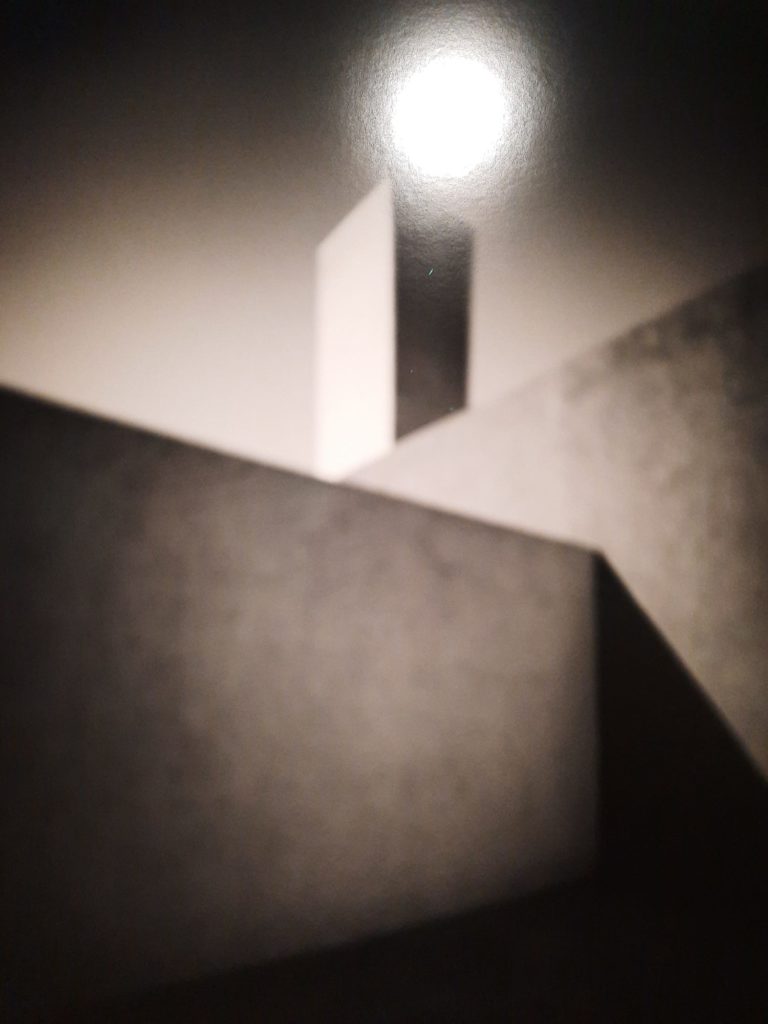

The Hayward Gallery exhibition is curated in a way which encourages us to take our time, take in the works. There are, I believe, only ten different series of work on view. Almost all of the works are large-scale prints in black and white, hung sparingly on the gallery’s walls. In the past I have almost rushed through the Hayward Gallery a little because I know the space is large and there is a lot to see. In this instance I found myself slowing down, calming down. The time Sugimoto takes over each image encourages time from his audience in return.

Mathematics And Science

One of the first texts in Hiroshi Sugimoto promised pictures which “animate concerns related to optical science and mathematics.” I’m not going to lie, we scoffed a little at that. It seemed like one of those phrases bandied about by curators solidifying the meaning of an artist’s work. But no, it turned out in this case that it was very literally true. Two series, Opticks and Conceptual Forms, best exemplify this.

In Opticks, Sugimoto photographs colour in its purest form. The title comes from Sir Isaac Newton’s 1704 work, in which he proved that light was made up of different colours. Similarly, Sugimoto has used a prism and mirror to split light into different colours, capturing the results with a polaroid camera. A bright upstairs room displays several enlarged prints. Pure colours are at the centre: blue, yellow and red. On either side hang subtle, sumptuous shades all the artist’s own. It’s remarkable how many look like Rothkos with their blended bands of colour. It’s difficult to remember that this is light, not pigment.

Downstairs visitors will find Conceptual Forms. In this series Sugimoto has taken German plaster models from the University of Tokyo’s collection, representing mathematical forms. The information panels outline the equations corresponding to each model, made monumental through Sugimoto’s lens. Having reached the limits of this series, Sugimoto began producing his own models in metal, pushing the shapes further with this more precise material. The objects and images occupy a room together.

These two series more than fit the bill for “animat[ing] concerns related to optical science and mathematics”. It’s another way in which Sugimoto experiments with the limits of photography and what it can capture. That this exercise can be so cerebral and so aesthetic at the same time is fascinating.

Final Thoughts On Hiroshi Sugimoto

In a relatively short space of time, I came to feel that I understood Hiroshi Sugimoto as an artist. His techniques may vary, but there is a core to his work which is consistent: his interest in photography, time, and translating concepts into visual forms.

Many of the works in the exhibition are so beautiful they deserve the viewer’s attention: I was pleased to see a reasonable amount of seating to allow audience members to take their time and soak in the works. Through the different series on view I was transported from Japan to America, to far off shores and even a Chamber of Horrors, but it all felt interconnected. Is Sugimoto at times a little self-indulgent as an artist? Perhaps – anyone that preoccupied with technique and control is bound to be. But the end result commanded time, respect, and often a hushed awe amongst my fellow visitors: not always an easy thing to achieve on the busy London art scene.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine on until 7 January 2024

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.