Dohány Utcai Zsinagóga & Magyar Zsidó Múzeum és Levéltár (Dohány Street Synagogue & Hungarian Jewish Museum And Archives), Budapest

The same complex in Budapest houses the Dohány Street Synagogue (Europe’s largest) and the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives. Together they document a community’s history, continuity and traditions in sometimes unexpected ways.

Introduction

In my last post, a long weekend guide to Budapest, I briefly discussed the history of Budapest’s Jewish community and some of the sights connected to it as one lens through which to understand the city’s development. Today we focus in on one location in particular: the Dohány Street Synagogue, whose complex also houses the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives.

The synagogue itself, also known as the Great Synagogue or Tabakgasse Synagogue, is Europe’s largest, with space for 3,000 people. It was built between 1854 and 1859 in the Moorish Revival style. Architect Ludwig Förster believing that in the (according to him) absence of a distinctive Jewish style, it was best to use architectural forms from ‘related peoples’. That is a whole can of worms which we are just going to park as necessitating further thought and discussion. In addition to the Great Synagogue, the complex includes a Heroes’ Temple, a graveyard and memorial garden, an extensive exhibition in the basement, and the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives.

The location of the Dohány Street Synagogue has two important historical connections. Firstly, the site of the museum marks where Theodor Herzl‘s birthplace once stood. In fact when modern political Zionism’s founder was born in 1860, it would have been in the synagogue’s shadow. The area was later redeveloped and the house torn down. The second connection is that Dohány Street formed one border of the Budapest Ghetto for a few short months between November 1944 and January 1945. 70,000 people were held in an area of 0.1 square miles (0.25 square KM). Many died, and many others were deported from here.

The Dohány Street Synagogue also suffered bomb damage during WWII, and neglect during the Communist period. It’s only from the 1990s that restoration began, with funding from Hungary and abroad. Today the synagogue complex can be visited daily except during on Shabbat. Check their website for timing and events.

Inside The Dohány Street Synagogue

So as I mentioned above, the architectural style of the Dohány Street Synagogue is Moorish Revival. Twin domed towers dominate its silhouette, with an imposing exterior wall protectively enclosing some of the buildings within. On closer inspection, the synagogue also includes Gothic, Romantic and Byzantine decorative elements: a real mix.

I spoke briefly in my previous post about how Budapest’s Jewish community split during a congress in 1868-69. The split was along religious lines. The vast majority chose Neolog Judaism, while the remainder retained their Orthodox practices and beliefs. Neolog Judaism is a Hungarian form of liberal and modern Judaism. These were the ‘assimilated’ members of Hungarian Jewish society, often middle-class, who wanted their religious affiliation to be the sole difference between themselves and their compatriots. That the Dohány Street Synagogue pre-dates the official schism by a decade shows how strong this contingent already was.

This desire for assimilation is evident in the Great Synagogue. The bimah (a raised platform from which the Torah is read) is not in the middle as is typical. The synagogue is instead oriented towards the front like a church. And it contains an organ (not now the original played by Franz Liszt), another atypical feature. Some of the interior architectural elements are the work of Romantic Hungarian architect Frigyes Feszl.

Once you’ve paid for your entry ticket, you can join a free tour of the synagogue. Enquire at the ticket desk as to the next departure times. And once inside, look for the flags to find your language.

Around The Dohány Street Synagogue

There are a few more things to see before we get to the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives. Let’s take a quick look now.

Upon exiting the Great Synagogue, the first place you will come across is a cemetery. It’s not customary to have a Jewish cemetery adjacent to a synagogue (like it is with churchyards). Normally they are outside of city limits. But this one is a case of historical necessity. When the Dohány Street Synagogue became part of the Budapest Ghetto, the synagogue sheltered many hundreds of people. As inhabitants died during the winter of cold, hunger and disease, some were buried here in the synagogue grounds. Headstones or plaques commemorate some of those whose names are known. Behind the synagogue, in the Raoul Wallenberg Holocaust Memorial Park, is a Memorial to the Hungarian Jewish Martyrs. The work of Imre Varga, it takes the shape of a willow tree inscribed with names and tattoo numbers. Wallenberg was a Swedish diplomat who saved thousands of Jewish people in German-occupied Hungary.

Also adjacent to the Great Synagogue is the Heroes’ Temple. Added to the site in 1931, services take place here on weekdays and during the winter. It is a memorial to members of Hungary’s Jewish community who gave their lives during WWI, and was designed by Lázlo Vágó and Ferenc Faragó.

Finally, in the space below the Great Synagogue itself is an exhibition on the Budapest Ghetto. The exhibition is essentially text-based, with information panels and reproductions of images telling the story of this period in the city and synagogue’s history. There is a lot to take in (in terms of volume and content), and the atmosphere in the underground space can feel a little stifling, so while we had a quick look around we did not spend enough time to read everything.

The Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives: A Multi-Sensory Approach To Culture

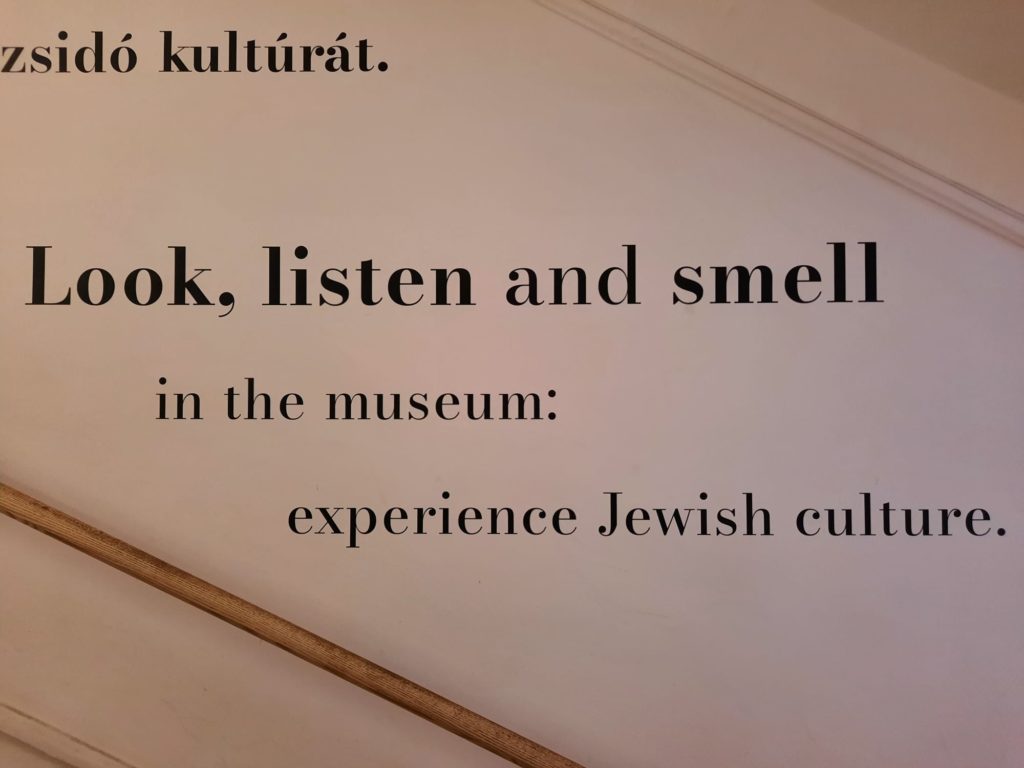

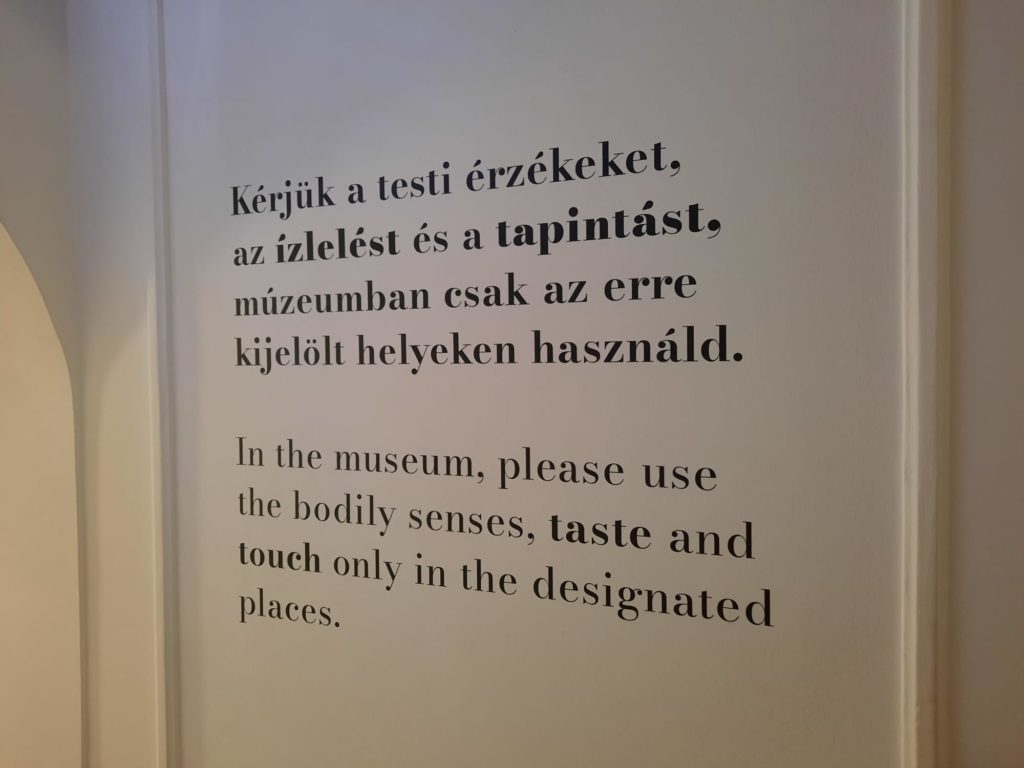

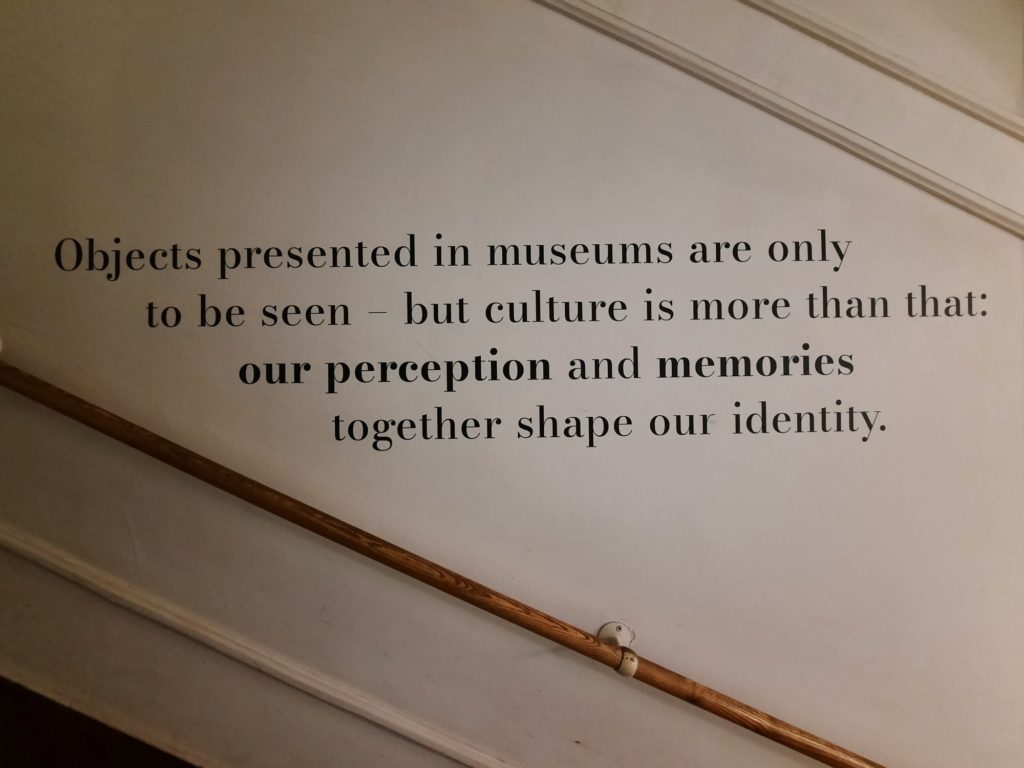

What struck me as soon as I entered the Hungarian Jewish Museum was how boldly it sets out its vision. This institution is a guardian of important objects and documentation. But more than simply aiming to exhibit and describe items from these collections, its aim is to engage the visitor’s senses in order to experience Jewish culture. For me, as a student of museums and of history, the statements lining the stairwell were an exciting and tantalising precursor. “Look, listen and smell in the museum: experience Jewish culture.” “Objects presented in museums are only to be seen – but culture is more than that: our perceptions and memories together shape our identity.” What wonderful intentions to set out in front of the approaching visitor.

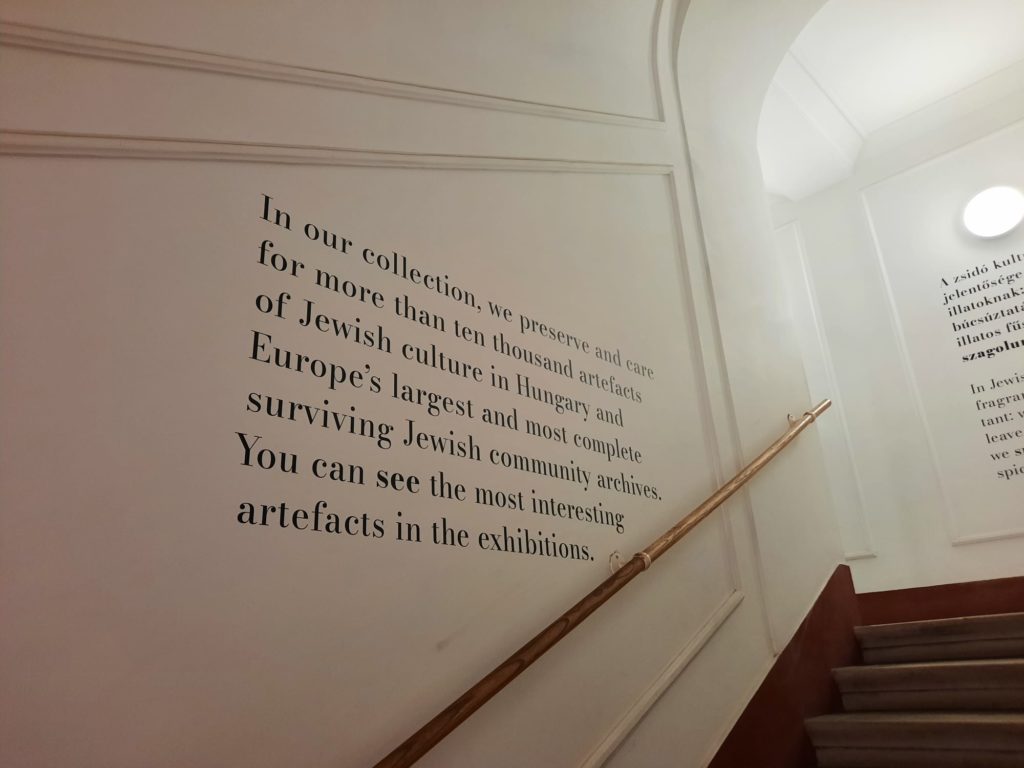

The Dohány Street Synagogue may be Europe’s largest, but the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives is one of the oldest Jewish museums in the world, dating to 1909. It’s been on this spot since 1931, when Lázlo Vágó and Ferenc Faragó purpose-designed this building as well as the Heroes’ Temple. Because of its age, and the smart actions of staff who concealed the collection during WWII, it’s one of the most extensive Jewish community archives and collections anywhere. The collection includes historic and Judaica objects, books, photos, fine art, and more.

As well as what is on display here the museum has an exhibition in the Rumbach Street Synagogue nearby. The Politzer Saga exhibition is the immersive story, told through film, of a real Hungarian Jewish family. It seems a good way to bring history to life and help visitors relate to the decisions earlier generations faced.

Inside The Museum

The permanent exhibition of the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives is Tamid: Always. The museum states that “This exhibition presents the cornerstones of Judaism: ordinary days, holidays and major life cycle events in Judaism.” We see familiar things like commandments. Frequently musealised objects like menorahs and spice boxes. And everyday objects we see less frequently in a museum context: kitsch tchotchkes, for instance. Roman items remind us how far back Budapest’s history goes. While a pin bearing Theodor Herzl’s face is a reminder of the site we’re standing on as well as the community’s political history.

If anything, I was a little disappointed that the manifesto promised in the stairwell was not more radically visible in the museum space. The permanent display is pretty static, with no opportunities I saw to engage more senses than sight. Unless we take that vision as having a broader reach and including the museum’s work outside its walls.

It is nonetheless an interesting display, full of small details and usual and unusual objects which together build a picture of a community. Entry to the Dohány Street Synagogue complex is not particularly cheap: I felt it was worth it because I spent time seeing all the different elements, but may not have felt the same if I came only to see the museum. But it was by seeing everything that I did get some of that sensory input I was promised, and left satisfied and ready for more Budapest sightseeing.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.