Museum Of The Home, London

My first visit to the Museum of the Home since its 2021 reopening under a new name is an opportunity to see what has changed, and what has stayed the same in Hoxton’s hidden gem.

The Museum Of The Home: A Short History

It’s been a while since I last visited the Museum of the Home. And when I did, it had a different name. So I thought a good place to start might be a short overview of the institution’s history, and some of the major changes it’s seen over the centuries. Particularly as another major project has just been announced so my visit captures a moment in time!

Today’s Museum of the Home began life as almshouses. This was semi-rural Shoreditch back in the 1700s, and it was common for London’s guilds and other charitable individuals or organisations to set up almshouses for people who met certain criteria – their own aged members or their widows who had fallen on hard times, generally, provided they also met moral and behavioural standards. These almshouses, built in 1714, were for the Ironmongers’ Company. The funds to set them up came from one Robert Geffrye (pronounced Geoffrey/Jeffrey), a merchant who had served as Lord Mayor of London and Master of the Ironmongers’ Company. He and his wife died with no heirs. The fourteen almshouses had four rooms each (one room per resident), plus a chapel for mandatory church services.

200 years later, this was no longer a peaceful, semi-rural place for vulnerable residents to live out their days. So the Ironmongers’ Company moved the inhabitants further out in the countryside. London County Council purchased the site, in part to preserve the almshouse gardens: one of the few green spaces in Shoreditch.

From Almshouses To Museum

After extensive renovations (which actually destabilised the buildings by removing load-bearing features), the Geffrye Museum opened in 1914. Hoxton at the time was a centre for furniture-making, and the museum focused on a reference collection of furniture and interiors. Over the decades the furniture trade moved away and the focus shifted onto younger audiences (not unlike the development of Young V&A nearby). In the 1930s the curator, Marjorie Quennel, introduced rooms kitted out to represent different historic periods. This remains one of the museum’s most memorable and beloved features until today.

In the latter half of the 20th Century the museum underwent a few changes. It passed to the Inner London Education Authority, before becoming a charitable trust in 1991. A 1990s extension also added space for exhibitions, a shop, and education rooms. The 1990s was a busy time for the museum, as it was also when they established a herb garden in derelict land next to the site. The museum could now tell the story of domestic gardens through the ages as well as domestic interiors.

The next big period for the museum occurred recently. In 2018 it shut its doors for a major renovation project. Architects Wright & Wright undid some of that 1914 destabilisation, and opened up new exhibition space at the basement level and in the former matron’s house. The museum changed its name in 2019, to the Museum of the Home. It reopened in 2021, with 80% more exhibition space and 50% more public space. This is my first visit since its reopening, so let’s see how it compares.

Exploring The Concept Of Home

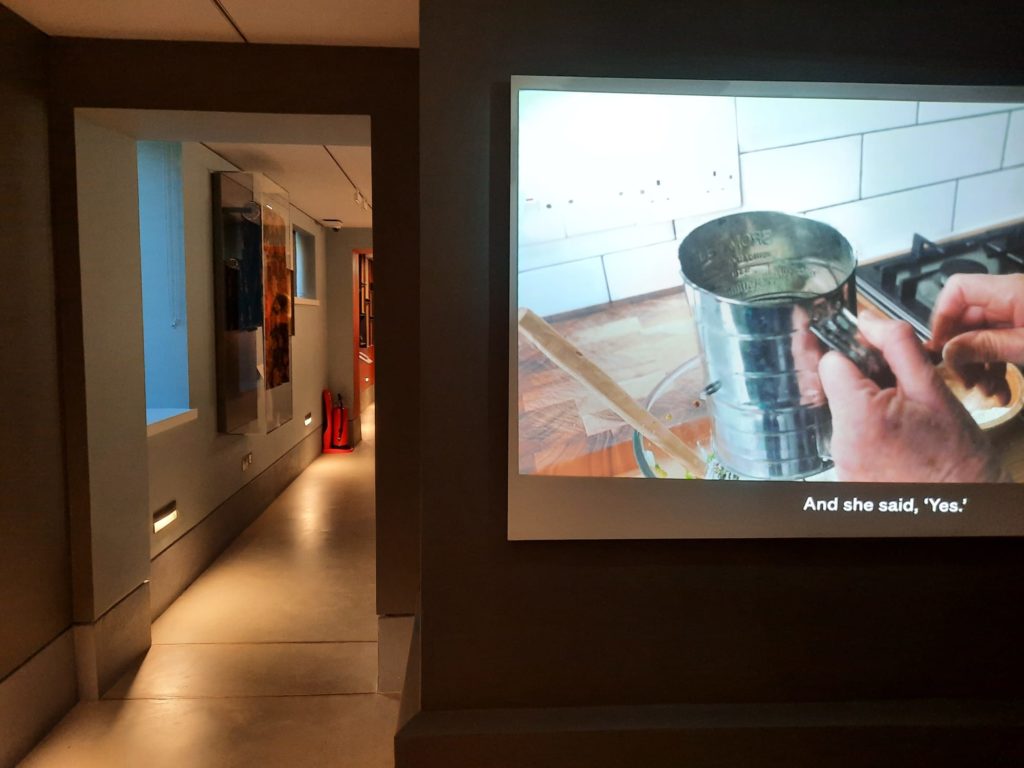

The Museum of the Home have put their additional exhibition space to good use, exploring the concept of home. By this I mean not what did homes look like through history, or what type of objects do we have in our homes, but what does home mean? Is it a place? People? A feeling? Something else? There is no expectation that home is the same thing for everyone, so the question really is: “What does home mean to you?”

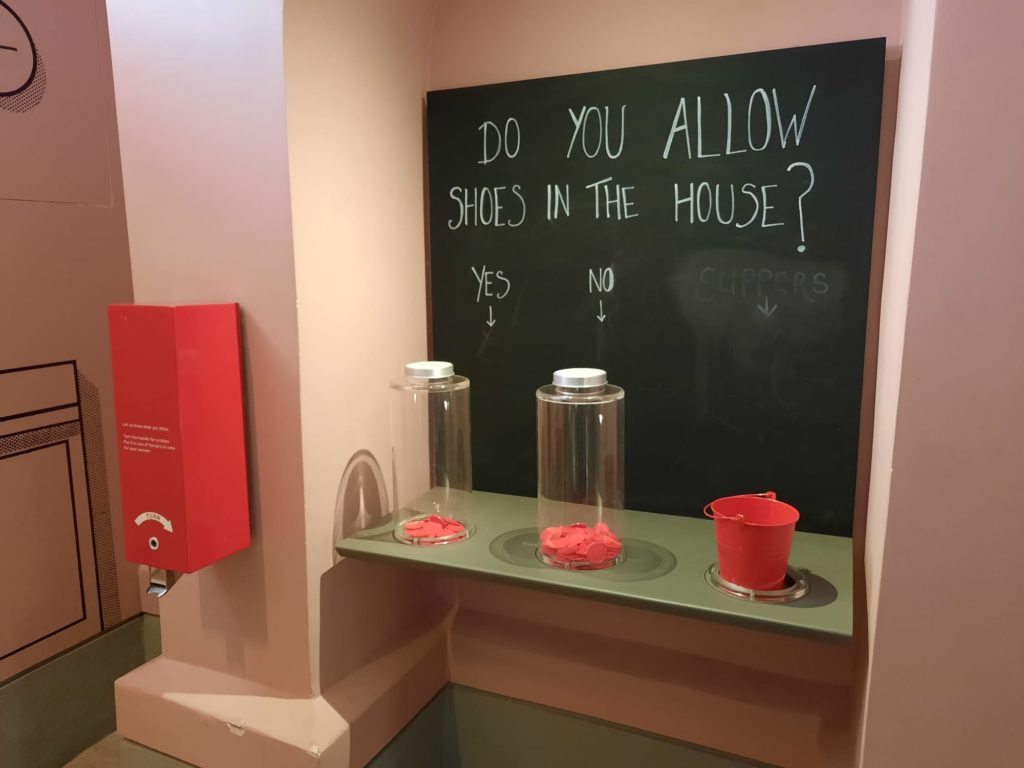

To delve into this question, there is a focus on personal stories, as well as drawing on a variety of objects from the collection. The groupings of stories and objects are thematic, for instance looking at where objects in your home came from, how the interiors of our homes are shaped by social codes, and how we live in our homes. I liked seeing stories from immigrant communities as part of the main narrative: the updated galleries will extend this further. There is also a playful element to this space: for instance I grabbed a counter to vote on whether or not shoes are allowed indoors in my home (they are), creating a connection and dialogue with other visitors past, present in future.

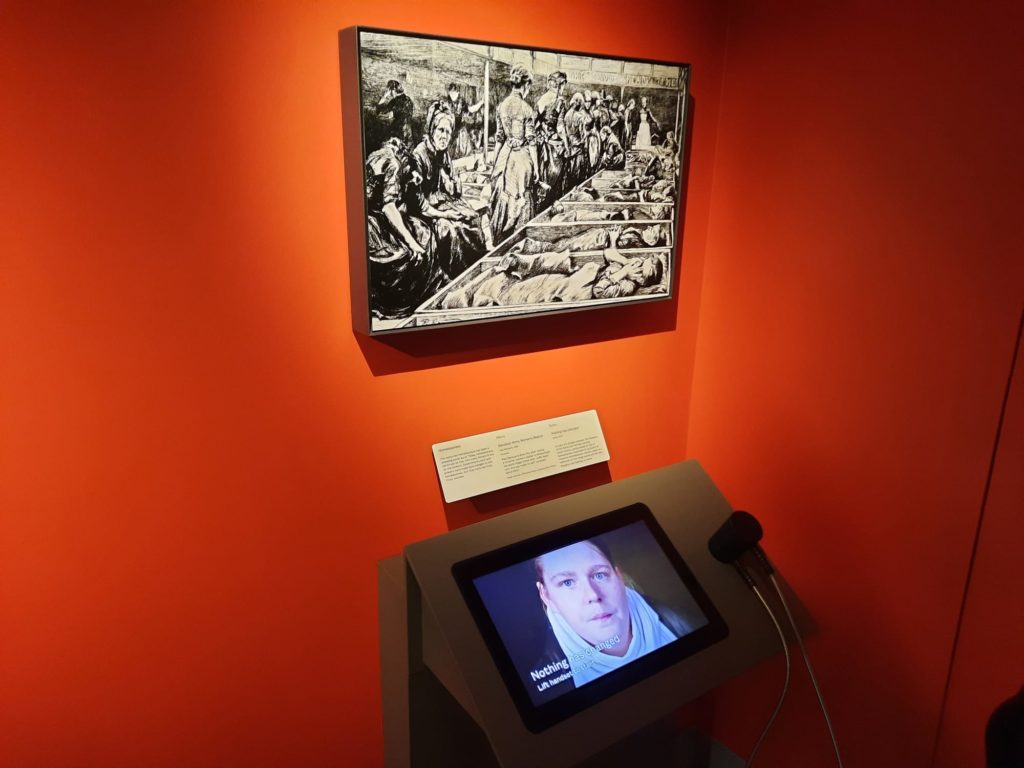

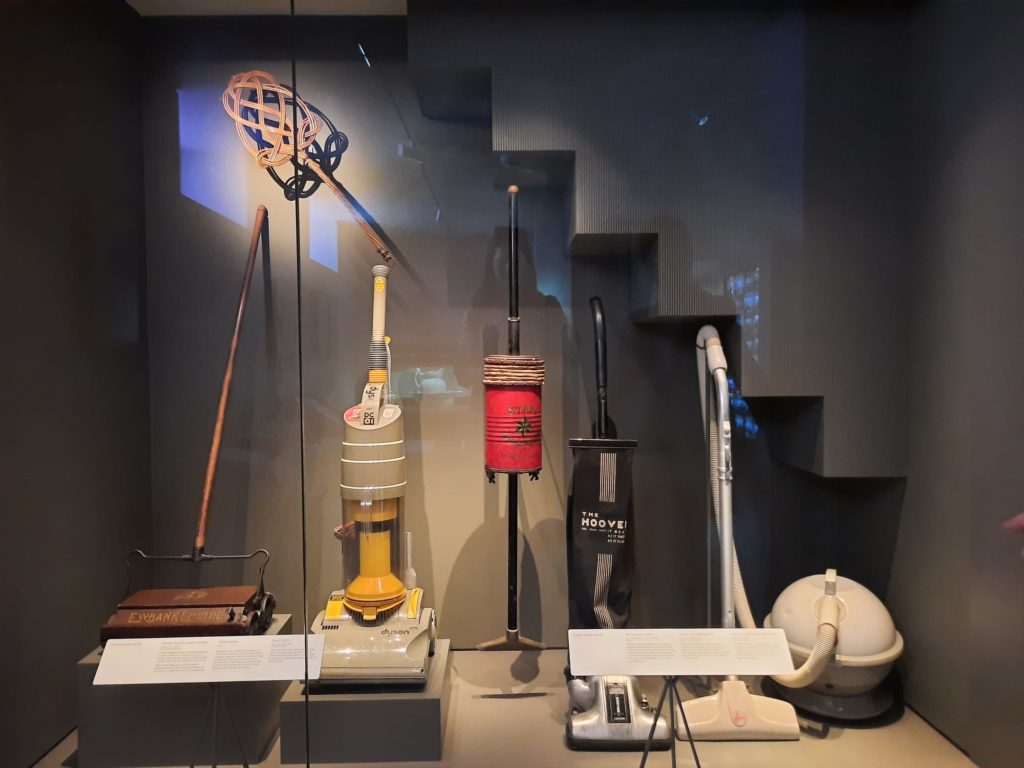

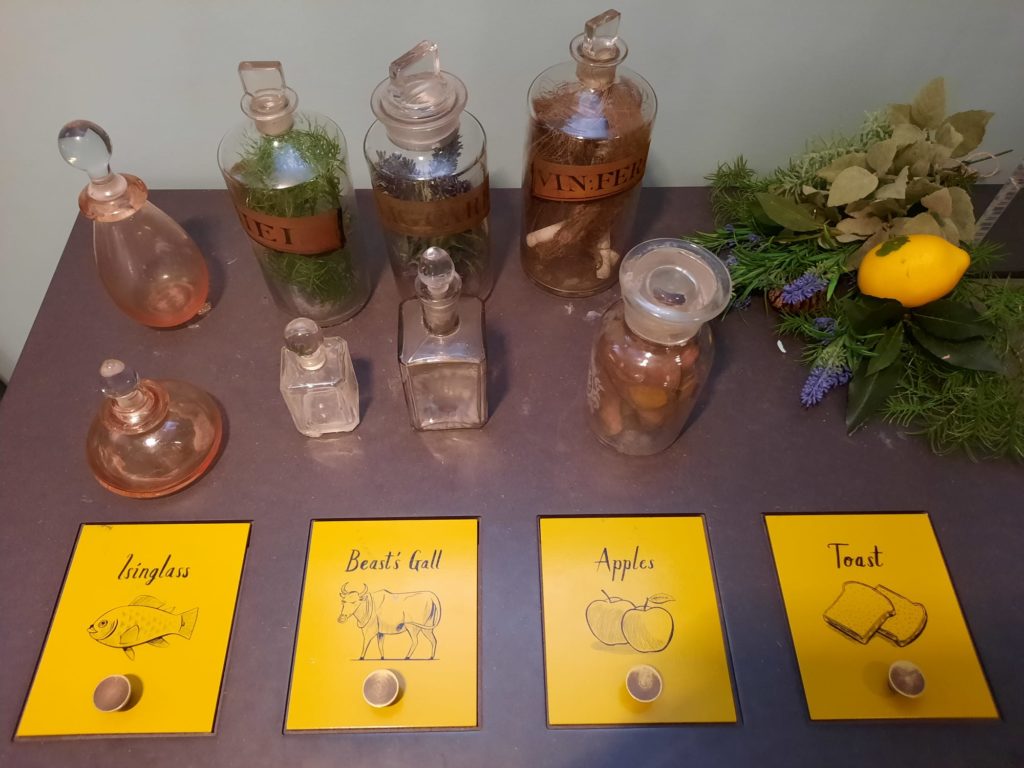

This new space emphasises interactivity and different ways of taking in information. You can listen to people’s personal stories. The displays engage different senses, for instance household cleaning remedies you can smell. You can sit on a sofa and play Super Mario Kart with a friend. Or take a seat in a kitchen and leave your comments on a discussion board. There’s a lot of information here, but it’s presented as a smorgasbord of things you might be interested in, rather than a hierarchy of information to take in and learn.

Rooms Through Time

After a brief ‘Domestic Game Changers’ display on transformative technologies, you arrive upstairs at what most people will remember from any previous visits to the Geffrye Museum: their Rooms Through Time display. Starting in the 1630s, this is a series of staged rooms representing different historic periods. The majority run along the length of the renovated almshouses, with the most recent in the modern 1990s extension.

I’m glad that the Museum of the Home knew better than to mess with this tried and tested formula. It’s fun seeing different historic periods brought to life, as if the residents just left. And it’s amazing really what a difference it makes seeing old furniture and objects in situ. Seeing how those fussy heirlooms once looked right at home, for instance. And sometimes you need to see how people used their communal spaces a long time ago to understand furniture we don’t live with today.

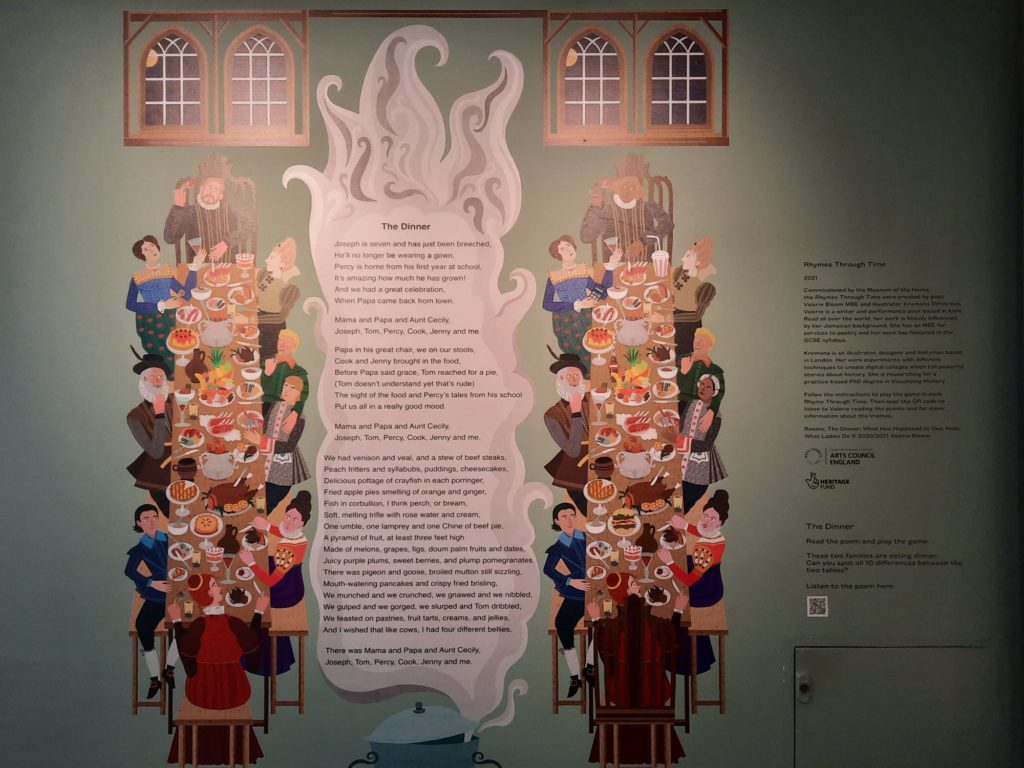

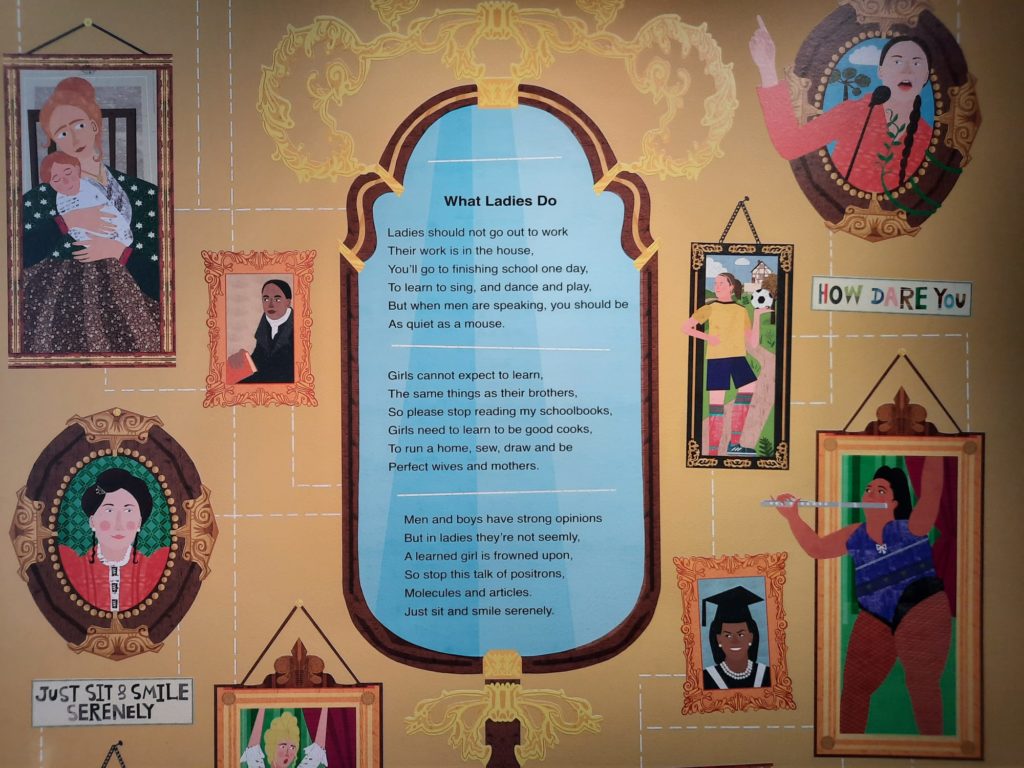

The Rooms Through Time displays have always been interspersed with interpretative spaces. This allows the rooms themselves to stay immersive, with the explaining and background kept separate. I don’t remember too much being different about the approach, but what I did notice overall is a new tendency to bring different voices into Rooms Through Time. This is done in a couple of ways. Firstly there’s more evidence now of different socio-economic levels in society, for example domestic workers (the focus is still on portraying middle class homes even if that’s no longer explicit). And secondly the spaces (and spaces in between) feature more voices. There’s a 1970s room set up as if a family of the Windrush Generation live there, for instance. And earlier on you can read a moving poem about the fate of an enslaved person.

It wouldn’t have been possible in 2023 to reopen whilst pretending that history is one linear thread with one default experience, but I thought the Museum of the Home team have done a good job of retaining what works while making it a broader view of history.

Confronting Difficult Histories

The other task the Museum of the Home team had ahead of them in reopening was deciding what to do about the more difficult aspects of their history. Namely, one Robert Geffrye and how he made his money. Let’s remember, the Black Lives Matter movement took off while the museum was closed for renovations, and statues commemorating figures who participated in or profited from enslavement were the target of much public outrage.

Robert Geffrye, as I said earlier, was a merchant. But his wealth was partly derived from the East India Company and Royal African Company, and he therefore profited from the forced labour and the transatlantic slave trade. His statue still stands outside the museum. Despite a public consultation returning a verdict around 70% in favour of removing it, the board of trustees decided to ‘retain and explain’. This was under pressure from the Culture Secretary at the time (more political interference coming soon when we go to Young V&A).

Personally, I believe that removing statues, or at least placing them in a different context with additional information, is more impactful than ‘retain and explain’. After all, how many take the time to read all the contextual information when they see a statue on a plinth? The mere existence of that statue implies the person depicted is worthy of our admiration. But anyway…

So with the necessity of keeping the statue of Robert Geffrye in place, the contextualisation of the almshouses’ origins moves indoors. In the former chapel, which houses a monument to Geffrye and his wife moved from their local church, the additional context of the origins of their wealth is explained in simple terms. It’s rather tricky for the Museum of the Home, because Geffrye funded the almshouses rather than having anything to do with the museum or its collections. I think they have done a good job within the constraints of the political climate.

A Successful Redevelopment Project?

So thinking about the redevelopment project, has it been successful? Certainly, this commentator asserts. It was first and foremost about the physical fabric of the museum. Destabilising choices during earlier renovations are now corrected. There is better accessibility for visitors with mobility issues or families with pushchairs. There’s a lot more space, which gives the collections displays room to breathe. And more spaces within the museum’s historic buildings are now open to visitors. There were a couple of details I wasn’t quite sure were as planned. Namely the corner café seems to have been shut for a while and I had to go around the building rather than entering opposite Hoxton Station. But it’s hard to say what’s behind that, whether snagging issues, funding/staffing problems or something else.

From a curatorial point of view, the redevelopment also allowed a shift and repositioning. The museum emerged with a new name, for one. And it’s less about objects and design now, and more about how we live and can live together well. In today’s fractious times this is a laudable mission. There are also more voices today in the museum than previously. This includes the voice of the visitor: I felt more part of the museum than when I have visited in the past, part of a conversation and part of the ever-changing city.

So all in all yes, a successful redevelopment project.

Final Thoughts On The Museum Of The Home

I enjoyed my visit to the Museum of the Home. It took me a while to understand the new layout, as I had previous visits to the Geffrye Museum in mind. And it’s not one you can easily dip in and out of, as its floorplan more or less requires you to walk the length of the almshouses and back, by which time you may as well finish off the more recent decades. But I liked the changes to the Rooms Through Time, as well as the inclusivity of the new content.

While you’re at the museum, don’t forget to take a stroll in the gardens (weather permitting, perhaps). Like the Rooms Through Time, distinct sections represent different ways of laying out gardens over time. A medieval herb garden. A knot garden. Later on, a kitchen garden. To add an additional layer to your garden experience, you can listen to an audio installation, Women’s Weeds. It tells the feminist history of women in medicine through themes like witchcraft, herbal healers and colonial medicine. You could also listen to this at home, it’s very interesting.

So the Museum of the Home remains a good choice for a free, informative and fun day out. Bonus points if you live on the Overground like I do, making transport super easy. And even more bonus points if you head for a tasty meal before or afterwards in one of Hoxton’s many Vietnamese restaurants. After all, this museum is all about what home is for the many different people who make up our fair city.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.