Marina Abramović: The Musealisation Of Performance

A response to the Royal Academy retrospective of Marina Abramović’s work. How does something as ephemeral as performance art transform into a museum exhibit?

Content warning: references to violence and sexual acts.

Marina Abramović at the Royal Academy

In a burst of post-Christmas activity I managed to squeeze in a visit to Marina Abramović, a large-scale retrospective of the artist’s work at the Royal Academy. However, I visited on the penultimate day: too late to write a meaningful review for you, dear readers.

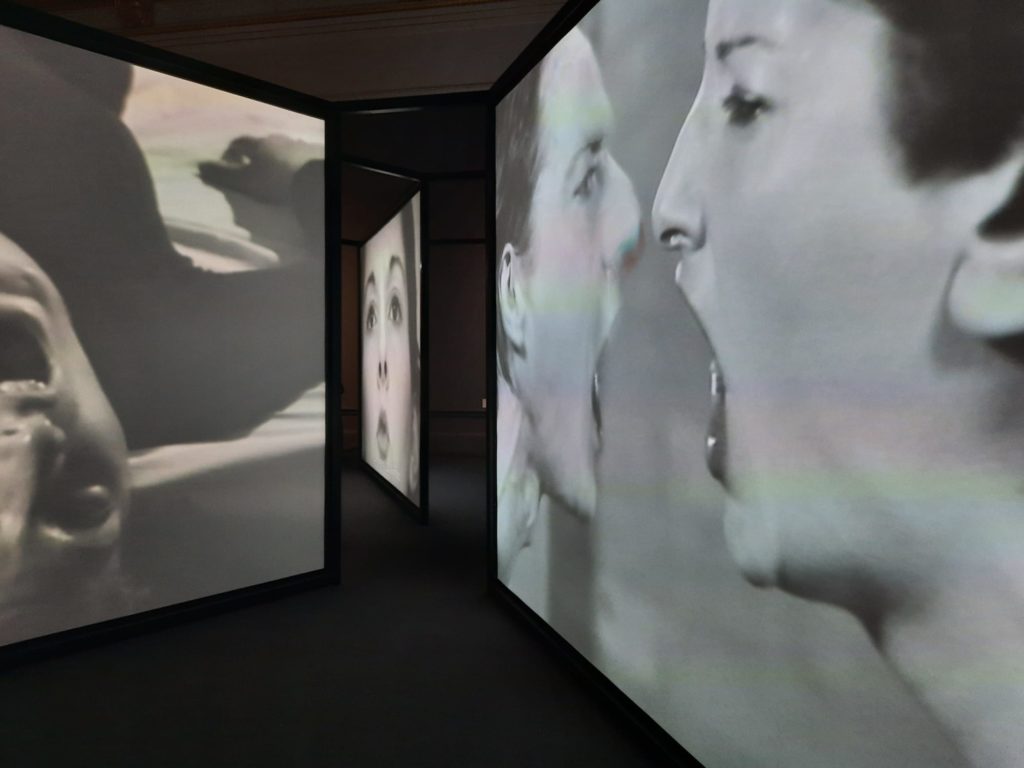

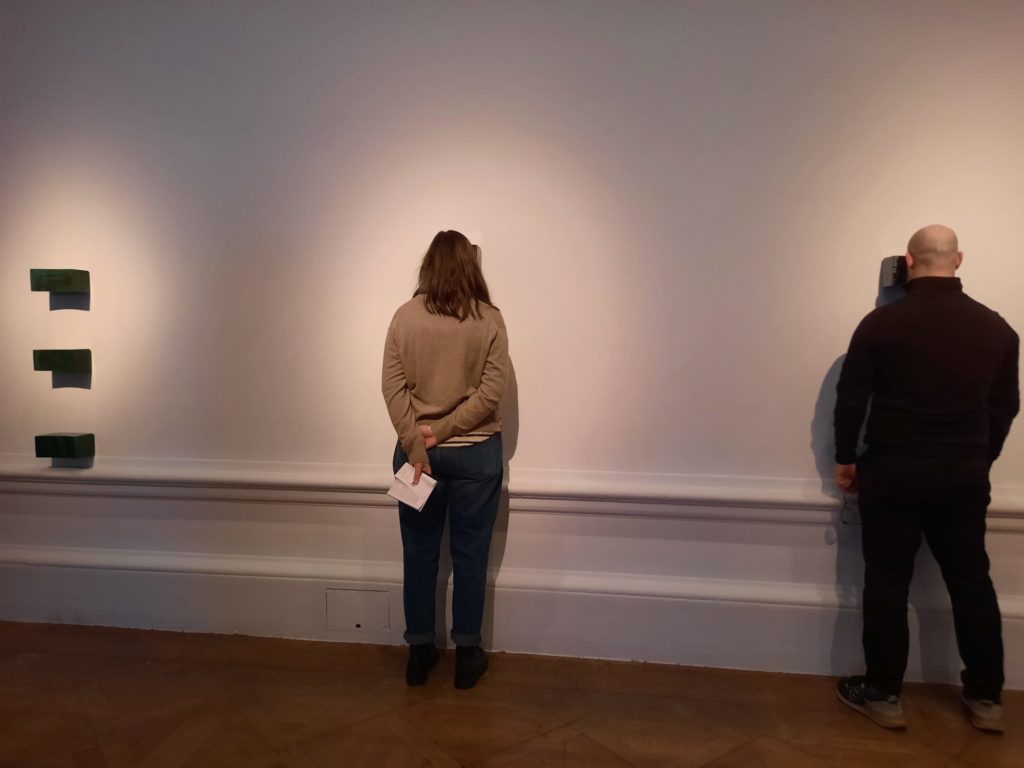

To give you a very quick summary, it was an impressive exhibition. It took over the entirety of the main RA galleries, which is a big space to fill. What was presented was a blend of large-format video projections of Abramović performing past works; documentation and objects associated with some of those works; and ‘re-performers’ repeating a handful of the past works on a schedule. Abramović’s (remote) presence was everywhere, with the added thrill of a live performance or two even if not by the artist herself. The works were nicely presented with dramatic colours and lighting to offset each space. And ultimately I learned a lot about Abramović’s career and work: the goal of a good retrospective.

Since I had almost missed out on seeing it, I didn’t think I would write a post on the exhibition. I was just happy to have squeezed in and experienced it. But as I progressed through the rooms I began to mull over an interesting topic. Performance art is, by its nature, fleeting. Only a very few people (and mostly art insiders) have experienced or will experience most works of performance art. But in order for something to enter the art history canon, does it need to move from being ephemeral to being tangible? And what is it that Abramović is doing that makes her so successful in this regard?

So after I got home I decided to do a little more thinking, reading and ordering of my thoughts. The results are contained within the following post: the opinions are all my own but I will cite a couple of works where you can do some further reading if you find this interesting too.

A History of Performance Art

Let’s start with performance art. If you have any pre-conceived ideas about it, it’s probably artists in the 1960s and 70s staging avant-garde performances using their own bodies. You might have heard of “Happenings“. Or you may be aware that some performance art is extreme, exposing the artist to, for instance, acts of sexual or physical violence. Let’s break down this movement with a few key facts and figures.

- Performance as art has its roots in the Futurist and Dada movements of the 1910s and 20s. Artists in these movements staged cabarets and other performances, and acted in public in ways deliberately designed to provoke and test the status quo.

- Performance art as we know it, however, really emerged in the 1960s. It is a broad movement, but (borrowing from Giesen, 2006) has some features in common:

- It shifts the focus of art from completing a finished work to a volatile and unpredictable live performance.

- It aims to break down conventional narratives through a focus on provocation, absurdity, irony, parody or destruction.

- “Performance art tries to blur the boundaries between art and reality, artist and spectator”: it is arguably the perspective of the audience that transforms the artist’s act into art.

Because performance art moves out of the frame of the painting and into the gallery, street or other public or private space, it challenges art itself (or at least the division between art and ‘real life’). Many performance artists also rejected commercialism in art, aiming – a bit like the Conceptual Art movement – to create works to which it is difficult to assign value. Performance artists often use their bodies, transgressing societal expectations or boundaries by doing things like putting themselves in harm’s way, engaging with knowing or unsuspecting audiences in unexpected ways, or performing feats which could be considered as extreme. A few famous examples of performance art are:

- I Like America and America Likes Me by Joseph Beuys, 1974. Beuys arrived in America, was taken to a gallery in an ambulance, spent three days enclosed in the gallery with a coyote, and then left again by ambulance.

- Yard by Allan Kaprow, 1961. A playful Happening in which the audience crawled and moved through rooms of tyres and other forms.

- One Year Performance (Time Clock Piece) by Tehching Hsieh, 1980-81. Hsieh punched a time clock in his studio every hour, on the hour, for a year.

- Trans-fixed by Chris Burden, 1974. Burden had himself crucified to a Volkswagen Beetle.

- Interior Scroll by Carolee Schneemann, 1975. Schneeman extracted a feminist discourse from her vagina and read it to the audience while standing naked on a table, amongst other actions.

A History of Marina Abramović and Performance Art

Marina Abramović is undoubtedly one of the most famous performance artists working today. Born in Belgrade (now Serbia, then Yugoslavia) in 1946, she grew up under strict regimes both politically and within her family. She studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade from 1965-1970. She continued her studies then began an academic career while simultaneously starting to create works of performance art.

Her first performance, Rhythm 10, took place in Edinburgh in 1973. Abramović jabbed knives between her fingers, swapping to a new blade each time she cut herself and then repeating the same movements following a sound recording. Rhythm 0, 1974, saw Abramović take a passive role, lining up 72 objects the audience could use on her. Over six hours the acts escalated to the point where Abramović was stripped, attacked, and had a gun held to her head.

After moving to Amsterdam in 1976, Abramović met fellow performance artist Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen). They began an artistic collaboration as well as a relationship. They created many works together over a decade, before embarking on Lovers in 1988. Each walking from one end of the Great Wall of China, they intended to marry when they met in the middle. Instead they separated. This schism initiated a period of reflection for Abramović in her life and work.

In recent decades, and since taking a different approach to commercialising her work (more on this shortly), Abramović’s fame within the art world has grown. She has taken part in the Venice Biennale, has been the subject of exhibitions at MoMA, the Guggenheim and other big institutions, and has created the Marina Abramović Institute (more on this later, too). The status of performance art as a whole, as well as her own art, is important to Abramović, which has led directly to some of the interesting practices I saw in the recent retrospective at the RA.

Ephemerality vs. the Art World

There is a tension at the heart of performance art. Is it all about the moment of performance, and therefore ephemeral? Or is it to be treated like other art and therefore documented, studied, and assigned a cultural and/or monetary value?

Marina Abramović actually provides a really interesting case study, because her attitudes have changed over time. While in the beginning she focused on performance and rejected commercialisation of her art, she has since seemingly embraced the art market as a way to ensure performance art is recognised, valued, and continues to exist beyond the life of a performance or artist. But the art market requires (for the most part) something tangible for a collector or institution to “own”. Soon after Abramović’s collaboration with Ulay ended and she resumed solo work, she partnered with a gallerist, Sean Kelly. And I very deliberately say partnered, because Abramović and Kelly have together worked on different ways to assign her art a commercial value, allowing it to enter private and later public collections and placing it firmly within the art historical canon (Wixon, 2014).

Broadly speaking, there are two ways for performance art to become more tangible. You can re-perform a work (a sort of licensing model). Or you can create an ‘official’ physical artefact of a performance (ie. documentation). Abramović has done both, and we will discuss them more below.

It’s important to note, though, that different performance artists have taken different approaches. For instance works by Tino Sehgal have no official documentation. If they change hands within the art market, a person approved by Seghal (or the artist himself) must effectively ‘uninstall’ the work and ‘reinstall’ it in its new home. This approach ensures integrity, but is difficult to continue beyond the artist’s career/lifespan. Other artists, including Abramović, have effectively created limited editions of their performances through documentation (photographs, film, written documents). This often involves either repurposing earlier documentation created as a record rather than an artwork in its own right, or creating documentation now with this dual purpose in mind.

The reading I’ve done on performance art, the art market and musealisation of performances (converting something into a museum exhibit) is very interesting. There is a strong connection with the first generations of performances artists getting older and thinking about their legacies. And also, undoubtedly, a desire for greater financial stability from their creations and therefore a softening on their rejection of commercialisation. And so performance art has, on the whole, become more tangible beyond the moment of its creation.

Musealisation Through Documentation

There’s been quite a lot written about performance art and its documentation. For some artists and scholars, there is a real anxiety about documentation corrupting the art itself. Is the artist thinking more about the documentation than the audience? Does the image of a work of performance art overtake the performance and become the art? Can we really think of these images as neutral archival documentation when there is a photographer there making choices about what they capture and how? See Auslander, 2006 and Büscher, 2009.

If we set aside these worries, documentation is fundamental to the afterlife of performance art. It is the proof that the performance happened. And sometimes it forms the instructions to be able to re-perform the artwork (the subject of the next section). In fact, Abramović sets out rules regarding documentation in order to regard a re-performance as authentic.

I mentioned above that Abramović’s documentation has undergone some changes over her career. In the beginning she thought about it as record or proof. Later she began to work with gallerist Sean Kelly to turn documentation into tokens which are assigned value within the art market and museum/gallery system. Because some of her works were co-created with Ulay, Abramović only had control over her entire documentary archive after purchasing the full rights to these collaborative works. But from the outset, she has demonstrated her belief that her performances are her intellectual property, including the records of them.

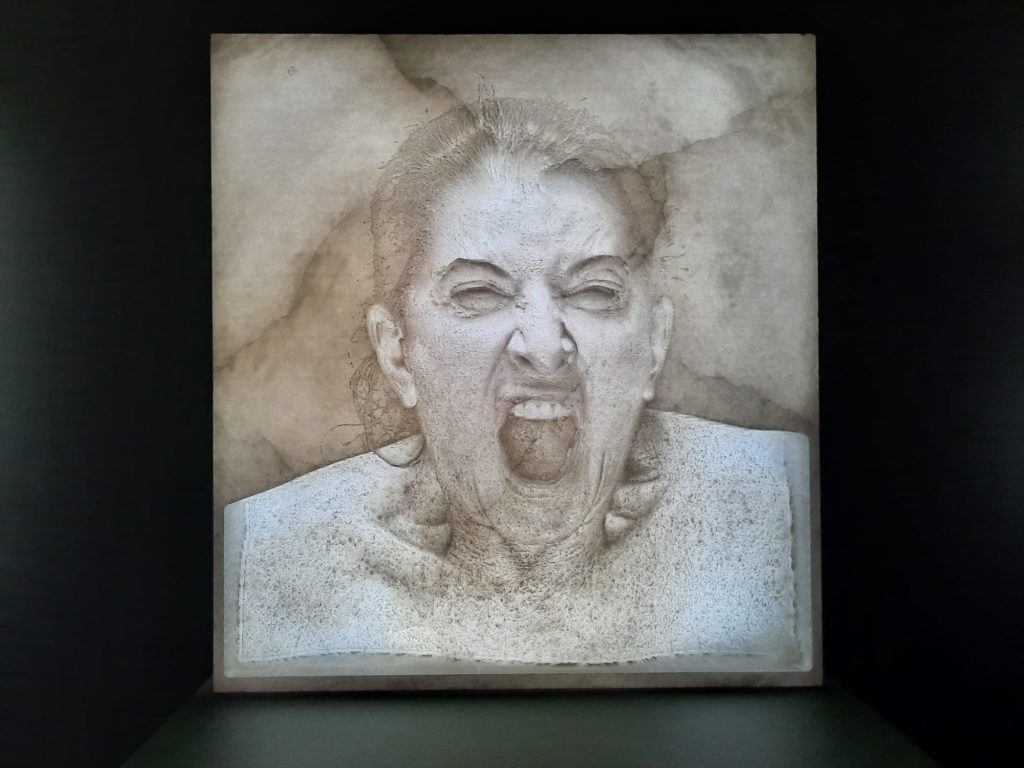

In the RA retrospective, documentation stood in for many of Abramović’s works. This took the form of photography, videos and objects. For museum audiences, such documentation is a guarantee of ‘authenticity’: we are seeing something which is ‘real’ and helps to contextualise the interpretations of Abramović’s artworks within the museum space. In more recent years Abramović has shown a playful and creative approach to documentation. To take one example, several recreations of Abramović’s face in alabaster were part of the exhibition. They allow the artist to capture facial expressions more accurately. They also blur boundaries once more: between documentation and artwork on this occasion.

Musealisation Through Re-Performance

The other way in which performance art can be transformed into a museum exhibit is through recreating it. This is often called Re-Performance in a performance art context. And as I’ve already suggested, there are different approaches to it. Tino Sehgal’s is one. Abramović’s is another. Through the Marina Abramović Institute, the artist trains performers to undertake approved re-performances of her work. But not all her work – works which involve physical harm or danger are excluded. A number of re-performances were part of the RA retrospective: I saw Nude with Skeleton in which a performer lies with a skeleton on top of them. In terms of the retrospective, live performance again added an element of authenticity and the exhibition would have been less successful without it.

Re-performance is also a way in which Abramović has engaged with the history of performance art and its status in the art world. For an exhibition at MoMA in 2010 she created Seven Easy Pieces, in which she re-performed seven works by other artists. To do so, she set out these rules for re-performance: “ask the artist for permission, pay the artist for copyright, perform a new interpretation of the piece, and exhibit the original material: photographic, video, relics” (Wixon).

That point about copyright brings me to a final important consideration when it comes to re-performance. The legalities. Copyright legislation works well for more traditional artworks, but less so for performance art. Codifying a ‘script’ for re-performance of performance artworks can help to bring it into the purview of these rules, thereby ensuring artists can enforce restrictions and be paid for their past works. Abramović knows this full well and it is part of her approach to her own and others’ work. On another note re-performance can also create legal complexities for artists and museums as it establishes an obligation to performers. Another point Abramović is more than familiar with.

Final Thoughts on Marina Abramović and the Musealisation of Performance

So within a relatively short post, I’ve attempted to cover a lot of ground. A history of performance art and Marina Abramović’s place in it. An explanation of different ways that artists and museums/galleries can make past performance artworks tangible to audiences today and turn them into exhibits. I learned a lot about the subject when preparing to write this post, and frankly could keep going ad infinitum. But I hope this has been an interesting overview for you as well, with some food for thought.

For me, the Marina Abramović retrospective at the Royal Academy brought a lot of these topics into focus. As a key figure within performance art, Abramović has the influence to shape conversations about the movement as a whole. Her rules for reperformance, her commercial experiments, and the Marina Abramović Institute are all at the forefront of the musealisation of performance art. While sentiments and responses towards this tendency are not consistent across the broad spectrum of performance artists, it does raise interesting questions about how we can and do assign value to works of art, what it means when a performance is transformed into a tangible artefact, and whether/how an art movement can remain provocative while claiming its place in the art historical canon.

I hope you will excuse me the indulgence of writing at length about an exhibition that you cannot now visit. In some ways this post is my own musealisation/re-performance of it: I have documented its existence, with my own interpretation. I’m probably not giving Abramović a run for her money though. Performance art takes a special vision and courage, and to take it to the level Abramović has requires much more besides.

List of References

- Auslander, P. (2006). The Performativity of Performance Documentation. Performing Arts Journal 84, 1-14.

- Büscher, B. (2009). LOST & FOUND: Archiving Performance. MAP media | archive | performance 1/2009.

- Giesen, B. (2006). “Performance Art.” In Alexander, J., Giesen, B. & Mast, J. Social Performance: Symbolic Action, Cultural Pragmatics, and Ritual, Cambridge University Press, pp. 315-324.

- Sandström, E. (2010). “”Performance Art”: A Mode of Communication.” MA Thesis, Stockholms universitet.

- Wixon, A. (2014). “Marina Abramovic: Methods for Establishing Performance Art in the Gallery and Museum System.” MA Thesis, City University of New York.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.