Holbein At The Tudor Court – The King’s Gallery, London

An exhibition centred on remarkable drawings, Holbein at the Tudor Court is marred only by having to jostle with fellow visitors to get close to the works.

Holbein at the Tudor Court

If you call an image to mind when you think of Hans Holbein, it’s likely a member of the Tudor court. Probably someone in fine clothing against a bluish background. Or perhaps The Ambassadors in the National Gallery with its peculiar optical illusion skull. Holbein’s ability to capture a likeness (and play the politics) saw him appointed court painter to Henry VIII by 1535, only a few years after arriving in London. And the Royal Collection still holds a substantial number of his works. Hence the current exhibition, Holbein at the Tudor Court, at the King’s Gallery (still the Queen’s Gallery on their exhibition page).

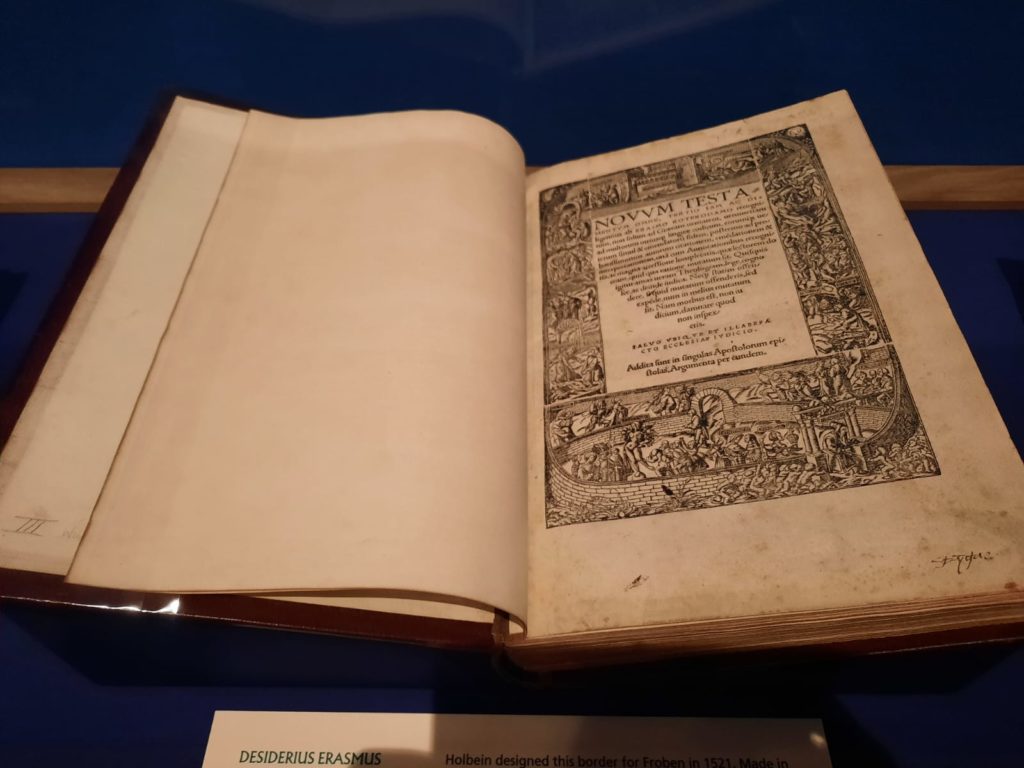

But let’s not go down the rabbit hole of today’s royal family. We’re here, after all, to talk about Hans Holbein and the Tudors. Hans Holbein the Younger, properly speaking. He was born in Augsburg, then the Holy Roman Empire and today in Germany, around 1497. Holbein started his career in Basel, which is of course now in Switzerland. But he was then a painter mostly of religious subjects, and the Reformation was making that a bit difficult. So with a recommendation letter from Erasmus in his pocket he came to England around 1526.

His first important client was Sir Thomas More, whose family portrait he painted. From there he built a reputation and a client base, reaching as far as the royal family. It turned out that England was no more stable than the rest of Europe, but Holbein seems to have navigated the troubled waters effectively. He returned to Basel a few times (citizenship could be revoked otherwise) and died in London in 1543. The traditional story is that he died of the plague, but there is no historical evidence for that. He would have been in his late 40s.

A Cleverly Constructed Exhibition

What Holbein at the Tudor Court does very well is to establish just what a remarkable artist Holbein was. It does this in two ways: by comparison with other artists, and by letting his works speak for themselves. It starts with the first approach. We learn biographical details about the artist, and see his works interspersed with those of other artists of the time. Court painter wasn’t a job for just one person during this period: there were multiple. With many others presumably vying for the position. And an exchange of paintings as artists were commissioned to depict marriages, victories, proposed spouses, and more. Art was an outlet for religious devotion, conspicuous consumption, declaring political allegiances, and more. So an artist moving in the right circles could do very well for himself indeed.

And so we see works by Holbein in these galleries, interspersed with the likes of Jean Perréal or Guido Mazzoni. Mazzoni’s terracotta head of a laughing boy is remarkable in its own right, but the paintings fall a bit flat. Even Holbein’s. There’s a scene of the resurrected Christ here representing his early work. It’s accomplished (and appropriate for Easter), but not exceptional. Exceptional applies better to when we round a divider and encounter the studies of Sir Thomas More’s family. The finished portrait doesn’t survive, so these are the preparatory sketches. They’re taken from a book of similar works, which presumably entered the Royal Collection after the artist’s death. Not intended as finished artworks, this is where Holbein captured likenesses, planned out compositions, and made little notes for himself on the sitter’s attire (eg. ‘black felbet’ for velvet, which I found rather endearing).

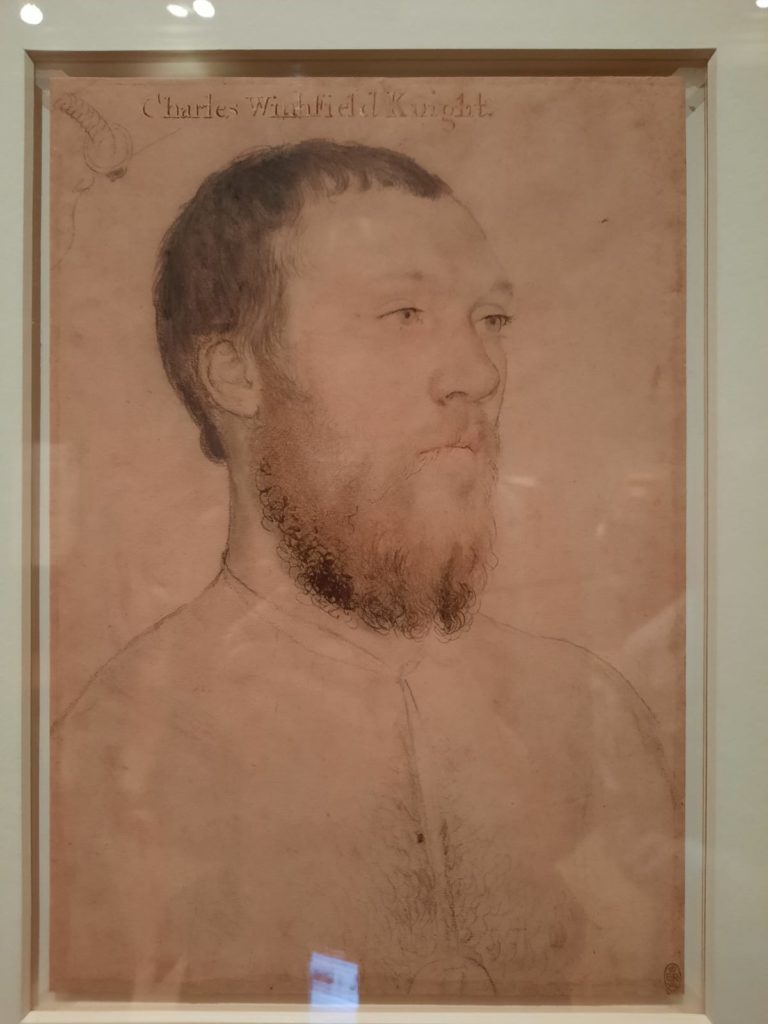

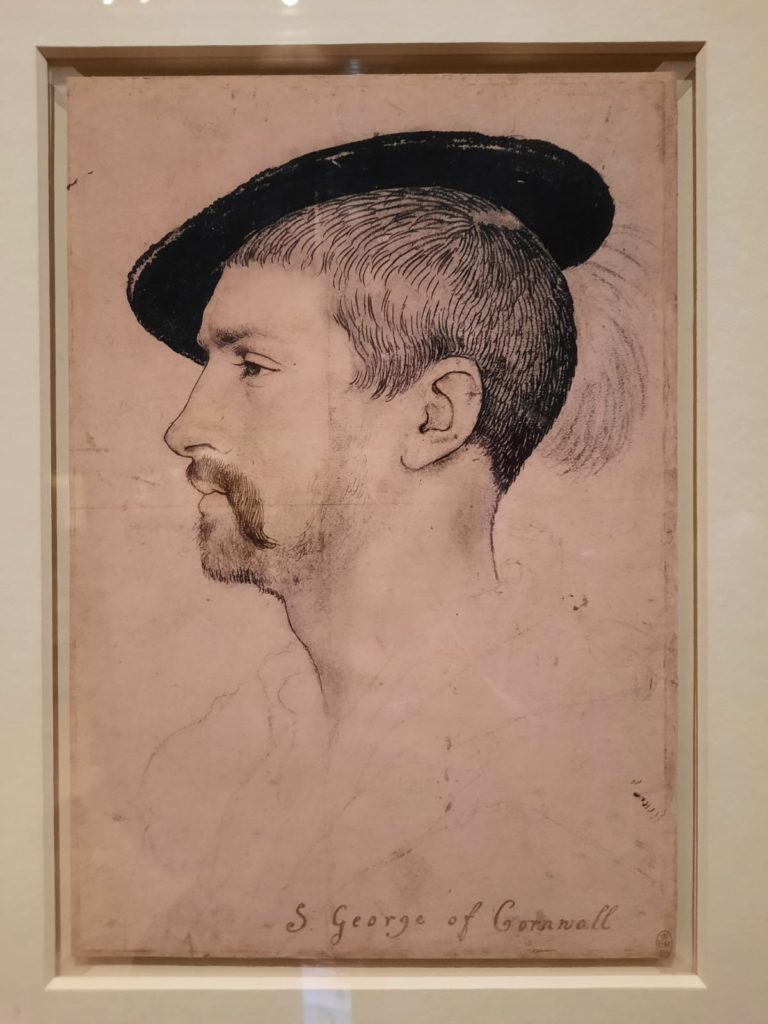

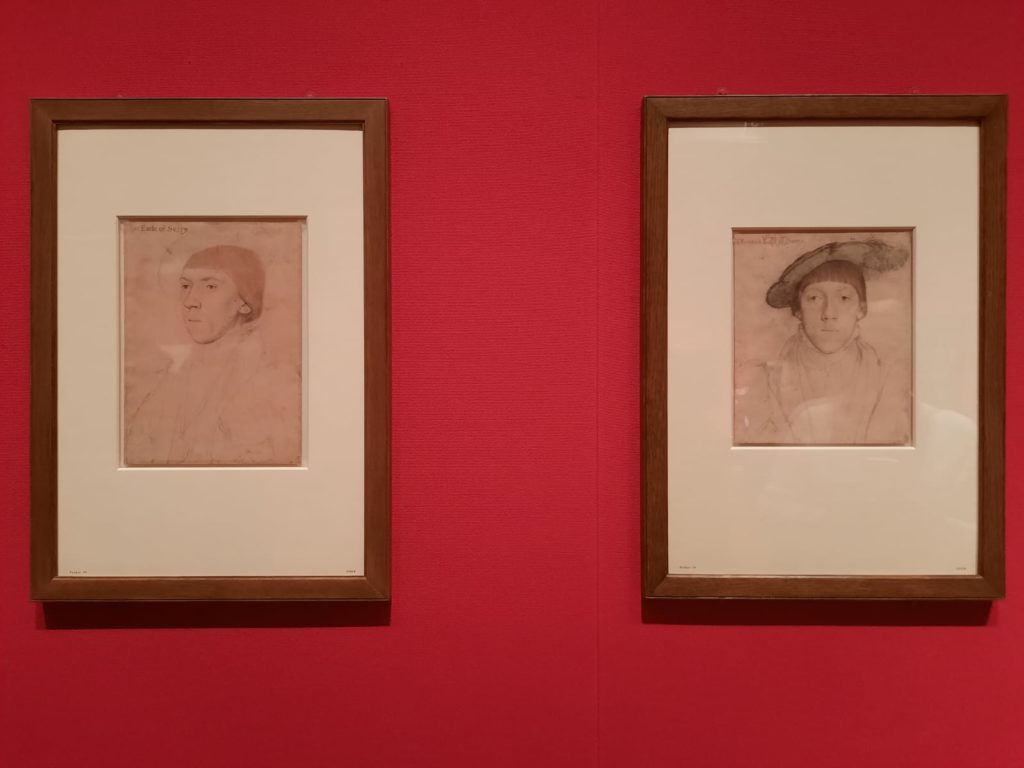

The portraits of More’s family are a taster for the next room, where various of these preparatory works line the walls. The book of sketches remained together in a volume for a good while before they were separately mounted. Names were added to most, although this isn’t always enough for us to know today who they depict. But no matter. The absolutely astonishing thing about the drawings is how well Holbein depicted the sitters. Compared to the flat, even slightly naive works by the other artists on view, you can see straight through the Tudor clothes and hair of Holbein’s sitters to the person underneath. As an artist he had a keen eye and an assured hand. The lines are simple, the coloured highlights hardly there at all. But as we look around the room, we see the Tudor court staring back at us: knights and ladies, poets and scholars.

Find a Quiet Moment

My mistake, in visiting this exhibition, was doing so on a weekend. It was busy. Even more so when you factor in gallery talks, and possibly Buckingham Tour groups passing through as well. I do think that ticket numbers factor into the overall success of planning an exhibition. It’s a frequent gripe I have when at the National Gallery. So it did detract from the experience, for me, that I had to continually jostle for position in order to see the sketches in as much detail as they deserve.

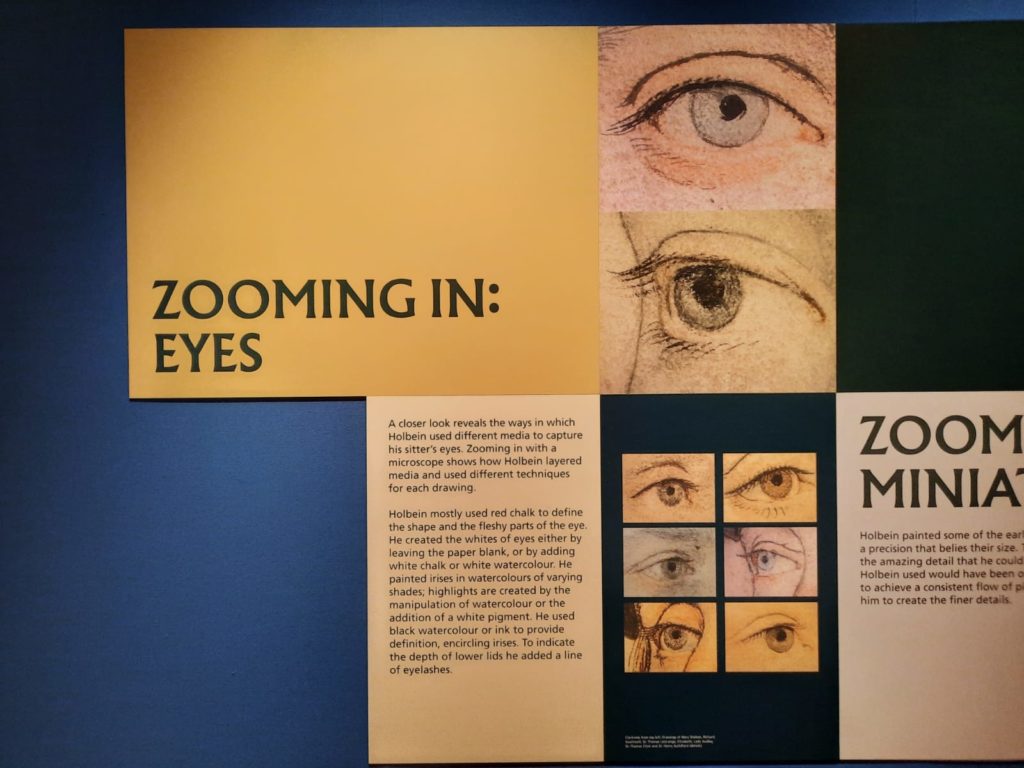

I would almost like to return before it closes (not long now) to see the sketches again. The rest I could take or leave. It tells a story, and does it well, but nonetheless when you reach the final room it’s a little disappointing to see conventional paintings of Henry VIII and his family again. The final few Holbein sketches of the royal family draw you in instead. I also recommend spending some time in the two rooms on Holbein’s technique. They are outside the main exhibition space so seem somewhat like an afterthought, but are excellent. They go into materials, artistic techniques, and modern conservation and investigation techniques, to deep dive into what makes Holbein so special. As many visitors skip these final rooms, they were also blissfully quiet when I visited.

So if you have the opportunity, do make time to see this exhibition. Works on paper by their nature are not always on display. It’s a wonderful opportunity to get up close to individuals separated from us by centuries: to observe their faces, their fashions, their vanities and foibles. And to learn about Hans Holbein the Younger, who captured them so wonderfully for posterity.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Holbein at the Tudor Court on until 14 April 2024. More info here.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.