When Forms Come Alive – Hayward Gallery, London

The Hayward Gallery’s current exhibition, When Forms Come Alive, is visually impressive. But does it do the artists and artworks a disservice by not going beneath the surface?

When Forms Come Alive

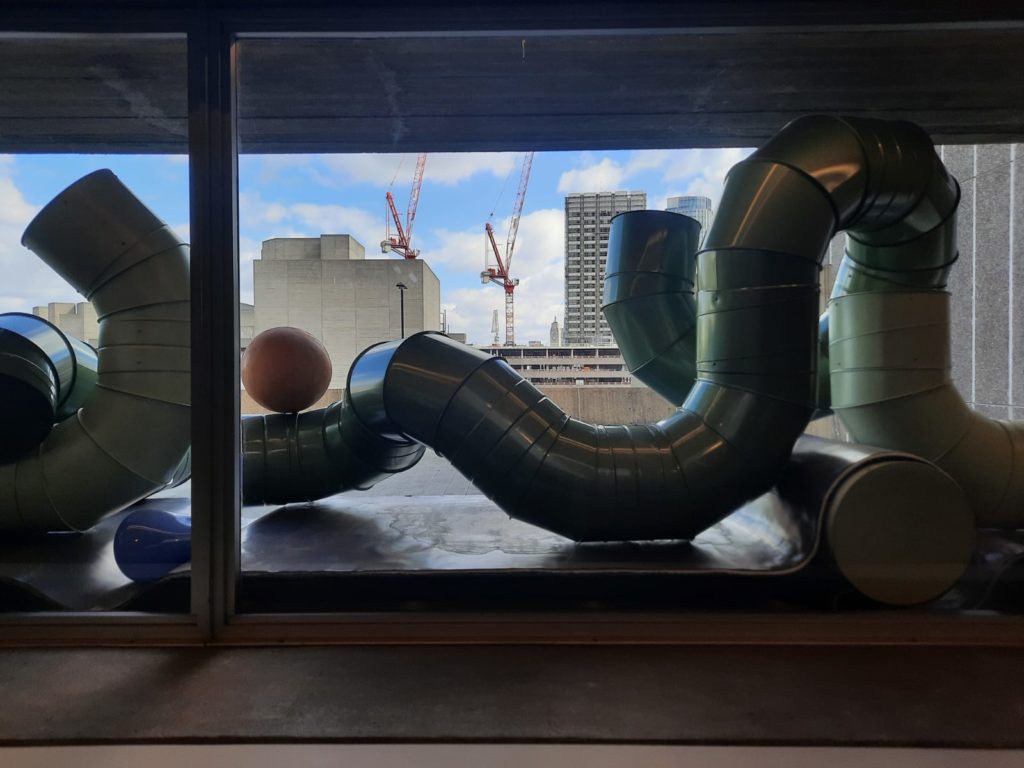

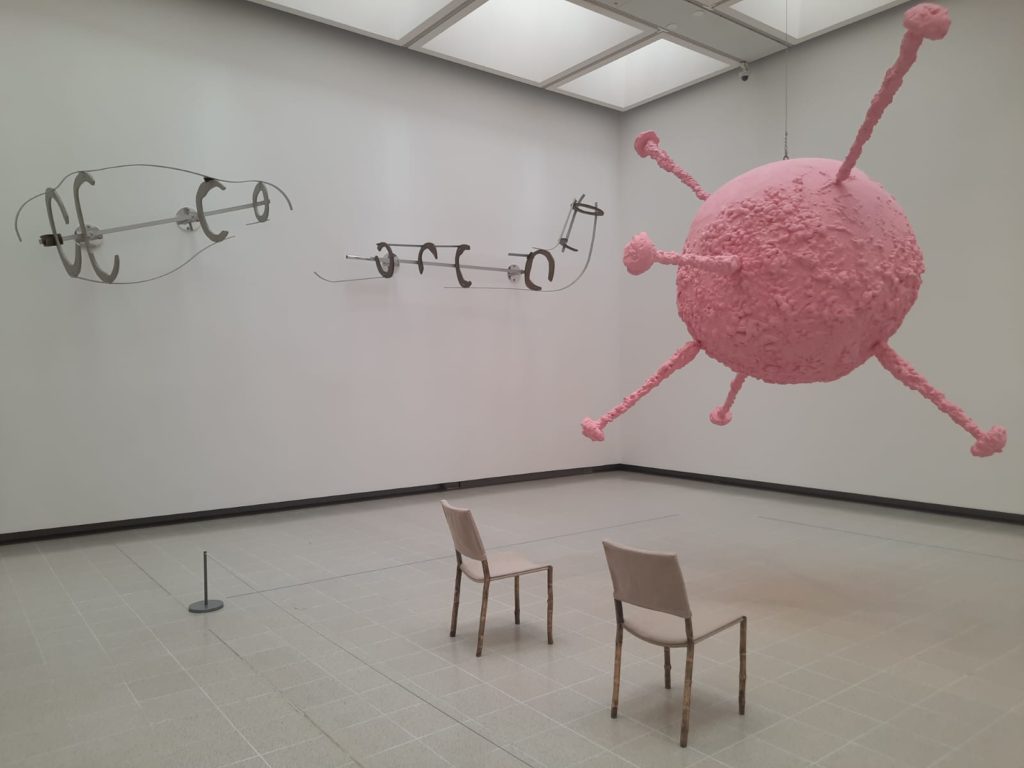

There is no doubting that this is an aesthetically pleasing exhibition. Instagrammable, even. From the first space you enter, where soft, organic forms swoop at you from the ceiling, to the shadows cast by a trio of Ruth Asawa’s works to finish, it is impressive. It’s only really on exiting that you wonder if there could have been a bit more to it.

When Forms Come Alive is an exhibition of sculpture. Large sculpture, for the most part. It’s not the first time we’ve seen something similar at the Hayward Gallery, whose sizeable spaces frankly lend themselves to installations and sizeable pieces. But typically the exhibition’s theme or purpose beyond ‘big sculptures’ is clearer: Afrofuturism, ceramics in contemporary sculpture, or even ‘trees’ as a theme. So we fall back to the Hayward Gallery’s website to explain what this one is all about:

“Inspired by sources ranging from a dancer’s gesture to the breaking of a wave, from a flow of molten metal to the interlacing of a spider’s web, the artworks in When Forms Come Alive conjure fluid and shifting realms of experience.

Undulating, drooping, erupting, cascading and promiscuously proliferating, these sculptures invite a tactile gaze, and trigger physical responses. In an era when our encounters are increasingly digitised and disembodied, these artworks call to mind the pleasures of gesture and movement, the poetics of gravity and the experience of sensation itself.”

www.southbankcentre.co.uk

So fluidity, movement, organic shapes. A sensuous and very physically grounded experience. Let’s see if the exhibition measures up to this tantalising description!

Do the Forms Come Alive?

The start of the exhibition is very promising. As soon as you enter, DRIFT’s Shylight (2006-2014) swoops at you from the ceiling. Its soft forms are reminiscent of flowers, clouds, or maybe jellyfish, moving in harmony to an unseen imperative. Over to the left is Michel Blazy’s Bouquet Final (2012). It seems static at first, until you realise it’s slowly churning out bubbles. A reminder to take time to look in order to see slow changes unfurling before you.

These, however, are the only kinetic works in the exhibition. Perhaps they’re here at the beginning to get this expectation of sculptures that are ‘alive’ out of the way at the outset? Don’t get me wrong, there are some beautiful and very impressive works on view. But after this engaging beginning, the remainder of the sculptures are static.

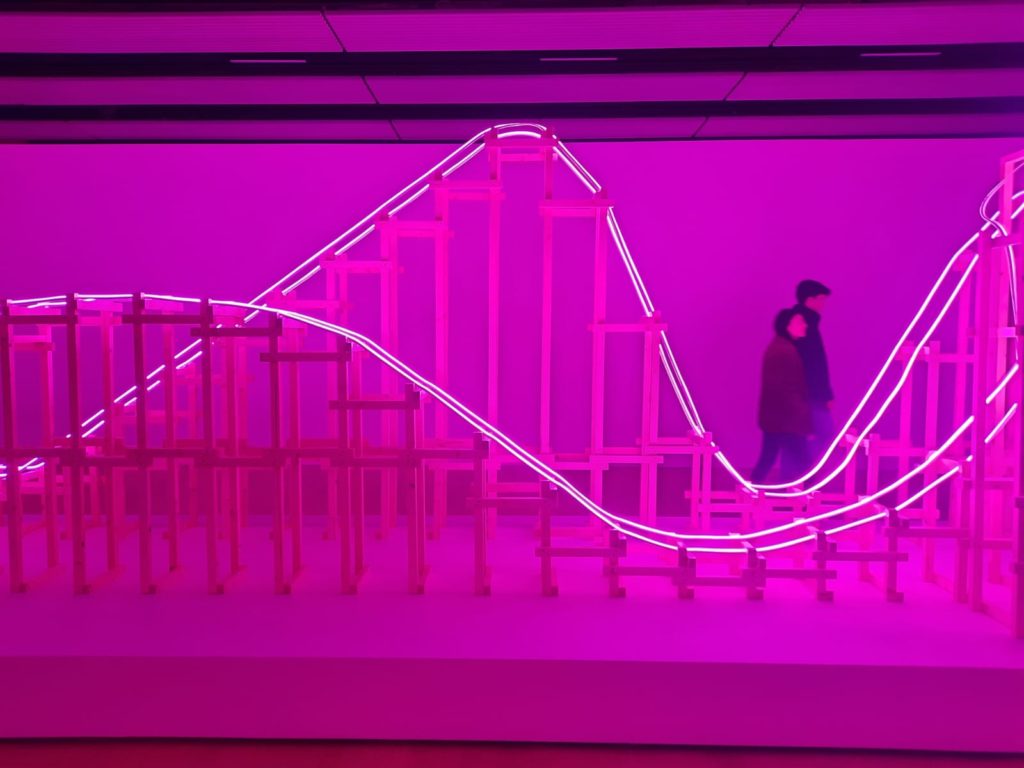

I found that, because the works tend to be quite large, it encouraged me to take my time and look at each one of them. The big Brutalist spaces of the Hayward Gallery are used to their fullest potential, and each artwork has room to breathe and for visitors to walk around it. I liked drawing back the heavy plastic curtains and bathing myself in pink light to experience EJ Hill’s A Subsequent Offering (2012). And the beeswax smell of the three works on view by Marguerite Humeau is peaceful and calming. The closest visitors come to touching one of the sculptures is with Tara Donovan’s Untitled (Mylar) (2011). A friendly staff member was on hand when I visited with a sample to touch, and answered questions about the artist’s process. Perhaps that one is too irresistible if you don’t let people feel the material for themselves.

Sensory But (Mostly) Without Touch

So thinking about the exhibition in the round, this brings me to two points. I think they’re related, let’s check in on this at the end.

The first is whether or not the exhibition lives up to its description. If you go back up to that quote I had near the beginning, it’s full of words like ‘gesture’, ‘molten’, ‘fluid’, ‘shifting’, ‘undulating’, ‘and the experience of sensation itself’. And in the sections above, I’ve talked about how my senses of sight and smell were engaged. There’s also a small sound component to the exhibition so hearing is covered off as well. But it’s difficult having an exhibition all about movement and physical sensation, while typical gallery rules are in place and you’re expected to be respectful, relatively quiet, and keep a safe distance.

The other point I wanted to touch on is how the explanations for the works stay mostly on the surface. I like an accessible exhibition where plain language is used to describe art so everyone can connect with it. But there is a difference between simplifying language, and only describing what you can see. Most of the text panels accompanying the works focus on the process of their construction, and how they look. This is a simplistic overview: there is some talk of the artists’ inspirations, references, struggles, etc. But it felt to me like there was something missing. Perhaps too much focus on keeping things playful does not give the audience credit for being able to appreciate art while understanding the complexities behind it?

And what ties these together? Reflecting on When Forms Come Alive, I came away with a feeling that it’s a ‘proper art’ response to those commercial exhibitions that keep popping up (I won’t name names, but you know all those ‘museums’ you see advertised that are actually just a fun experience and some photo ops for social media). It’s big, it’s bright, it’s colourful, it’s not too serious. But, for this visitor at least, it was not quite as meaningful an experience as some of my past visits to the Hayward Gallery. A difficult balance to strike, perhaps.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

When Forms Come Alive on until 6 May 2024. More info here.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.