National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks

The National Waterways Museum in Gloucester, managed by the Canal & River Trust, provides insights into how people once lived and worked on the UK’s waterways.

The National Waterways Museum Gloucester Docks (I Think…)

During a recent visit to see family in Gloucester, the Urban Geographer and I had the chance to explore a little. We were staying in Gloucester Docks: the most inland port in the country, now reimagined as a bustling shopping and leisure district. So it follows that we stopped in at the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks to learn more about the area’s history.

Only, for once I’m a little uncertain that I’m using the museum’s current name. I’m 90% sure it’s the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks. That remaining 10% is because I believe it’s changed its name and changed back again, but definitive information is a little hard to come by. Let me tell you the story so you understand what I’m talking about.

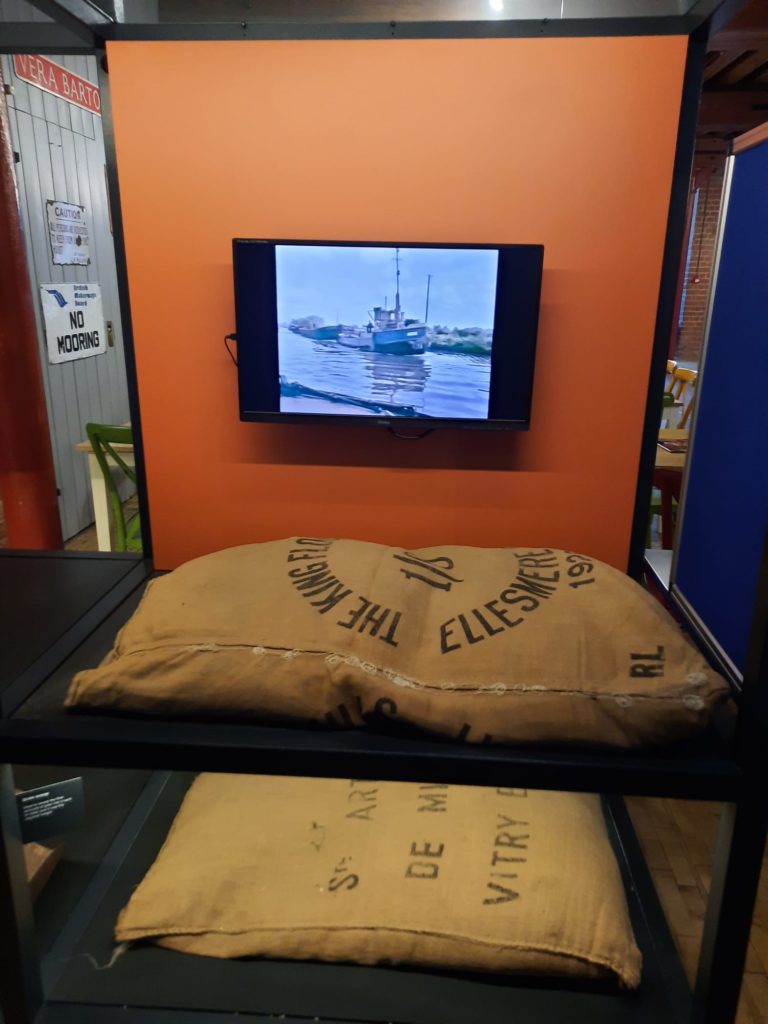

Like ports elsewhere in the UK, the volume of trade going through Gloucester Docks declined significantly as commerce changed in the 20th century. Rail and road transport became cheaper. Even London’s once-bustling docks shrank as larger container ships stopped further out on the Thames estuary. So a lot of Victorian infrastructure, including huge warehouses, had to adapt or die. As elsewhere, many of these buildings became flats. But the Llanthony Warehouse, Grade II listed since 1971, had a different future. It became the National Waterways Museum in 1988. Or a branch of said museum – there’s another at Ellesmere Port near Liverpool. And there was also a third (I believe) at Stoke Bruerne near Towcester.

But running museums isn’t easy, and sometimes requires creative solutions. In 2010 the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks became the Gloucester Waterways Museum. This decision to de-nationalise the museum was at least in part to allow it to access different funding streams. The museum’s Wikipedia page thinks this is still its identity, but it seems fairly certain from the Canal & River Trust website that it’s back to being part of the National Waterways Museum. What I can’t find out is when it changed back, or why. The Canal Museum Stoke Bruerne, which I think was denationalised at the same time, hasn’t changed back again.

What Is A National Waterways Museum, Anyway?

Part of the reason I’m still a tiny bit unsure about our museum’s identity is that the Canal and River Trust refers to the National Waterways Museum, Ellesmere Port as “the nation’s designated collection of waterways history”. But let’s assume that we’re correct about its name. This description, the “nation’s designated collection”, tells us the first part of what we want to know. This is the UK’s official collection relating to this topic. Generally being a national museum or collection implies funding from central government, but at this point I’m going to completely ignore the absence of the National Waterways Museum from this national museums organisation. This is meant to be a museum tour, not a detective story, after all.

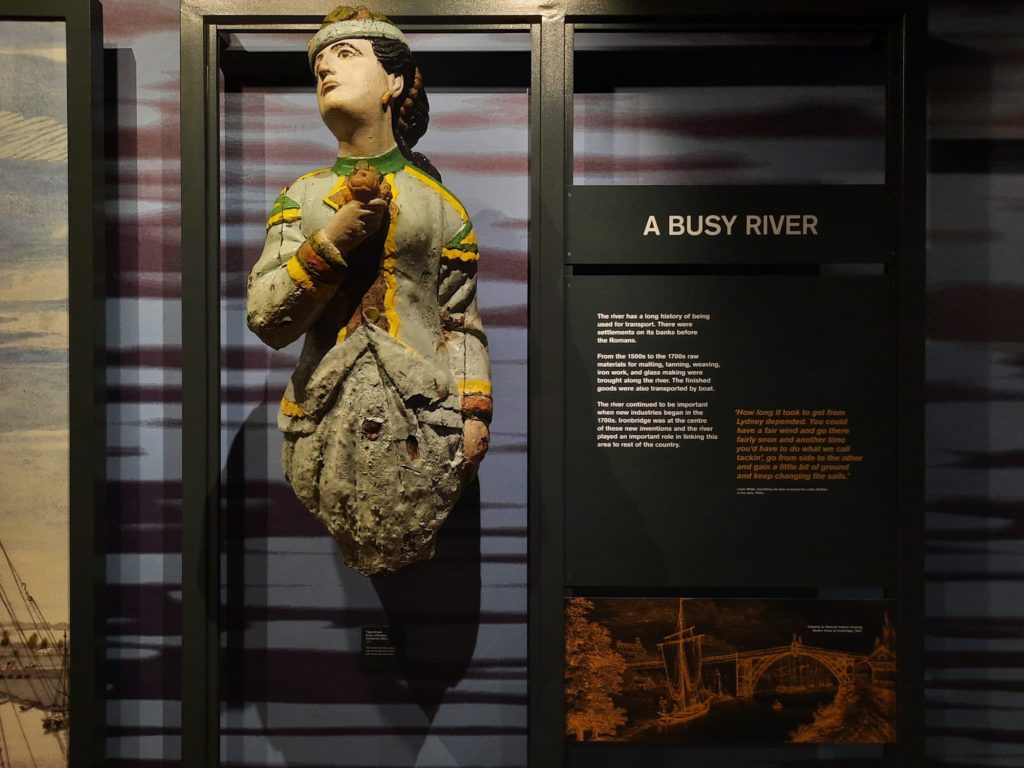

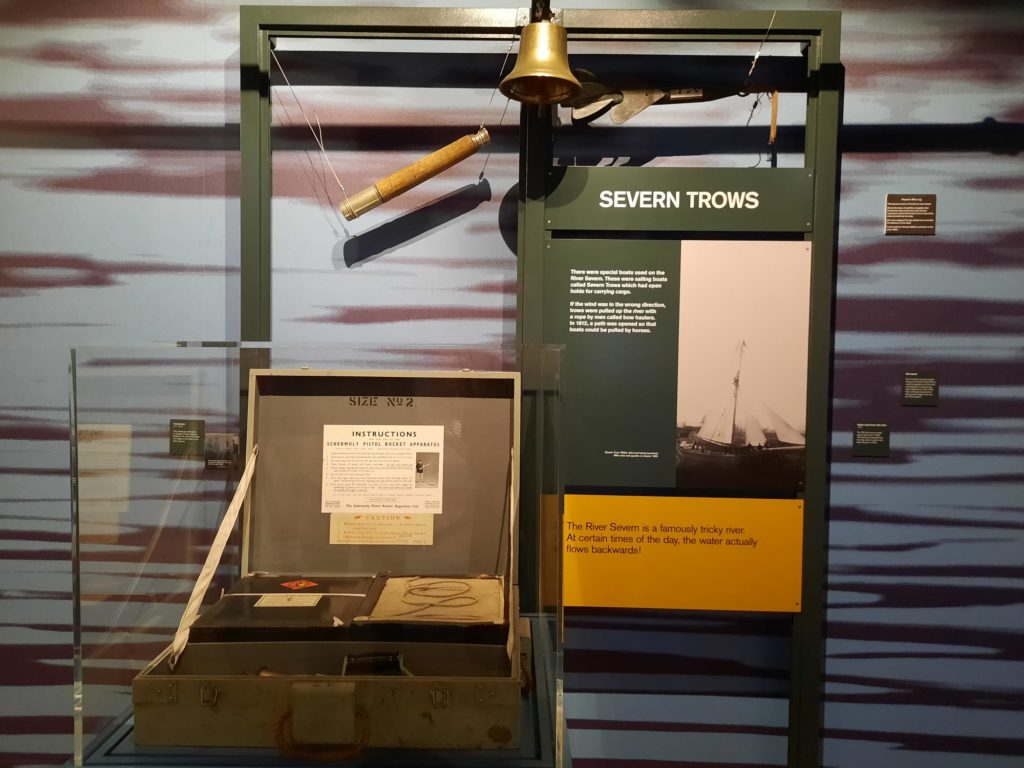

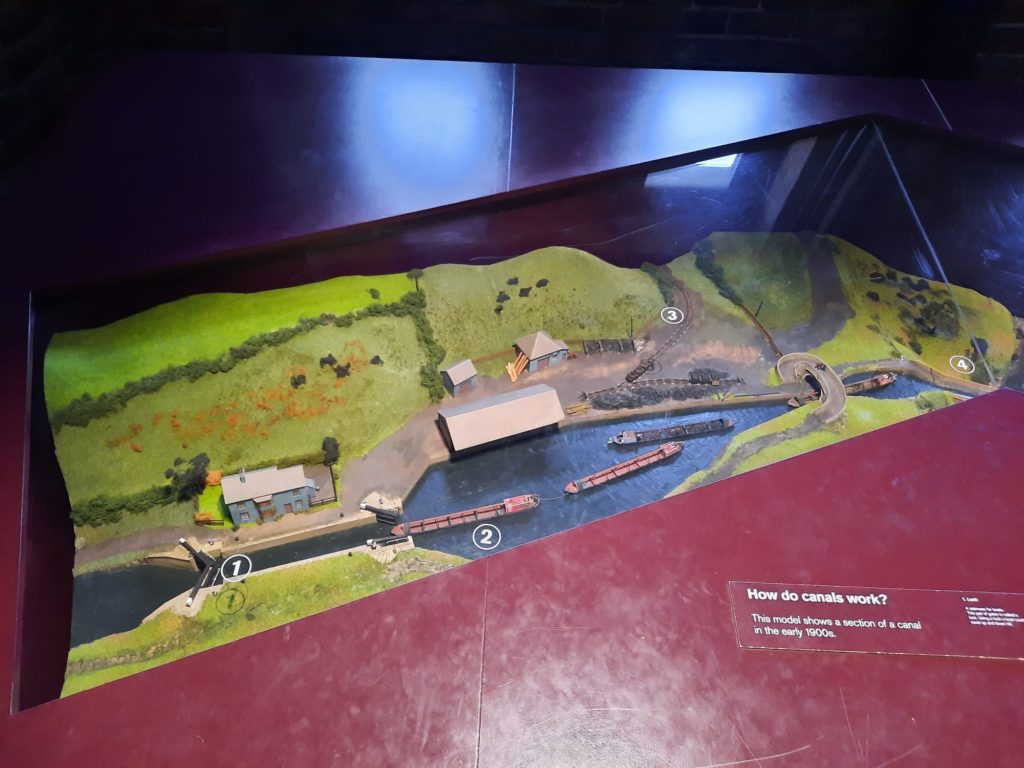

The other part to understand about a National Waterways Museum is what exactly we mean by waterways. And what we mean, in a nutshell, is canals and navigable rivers. The Canal and River Trust cares for a 2,000 mile network of such waterways. This includes looking after canals, embankments, culverts, reservoirs, bridges, locks and towpaths. However, at the height of the UK’s waterways, during the ‘Canal Mania‘ of the early 19th century, there were about 4,000 miles of navigable rivers and canals. A lot of these were built as speculative investments, and closed when they proved to be unprofitable.

Life and work on the waterways has of course changed a lot. Once, the people living on the waterways were also mostly working there too: transporting goods for instance or working as navvies. But they were in the minority, with most boats transporting goods. Today, more people live on the remaining waterways than at the height of the Industrial Revolution. But their reasons for doing so are very different. Living on a canal boat today is a lifestyle choice: sometimes dictated by the impossibility of getting on the housing ladder any other way, but affording a much better quality of life than the bargee families of yesteryear.

So there we have it. A National Waterways Museum is the nation’s keeper of collections and stories related to our canals and navigable rivers. Stories of immense expansion and busy commerce and industry over about 150 years, followed by decline and rebirth as important spaces for leisure and wildlife.

Just What Is In The National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks?

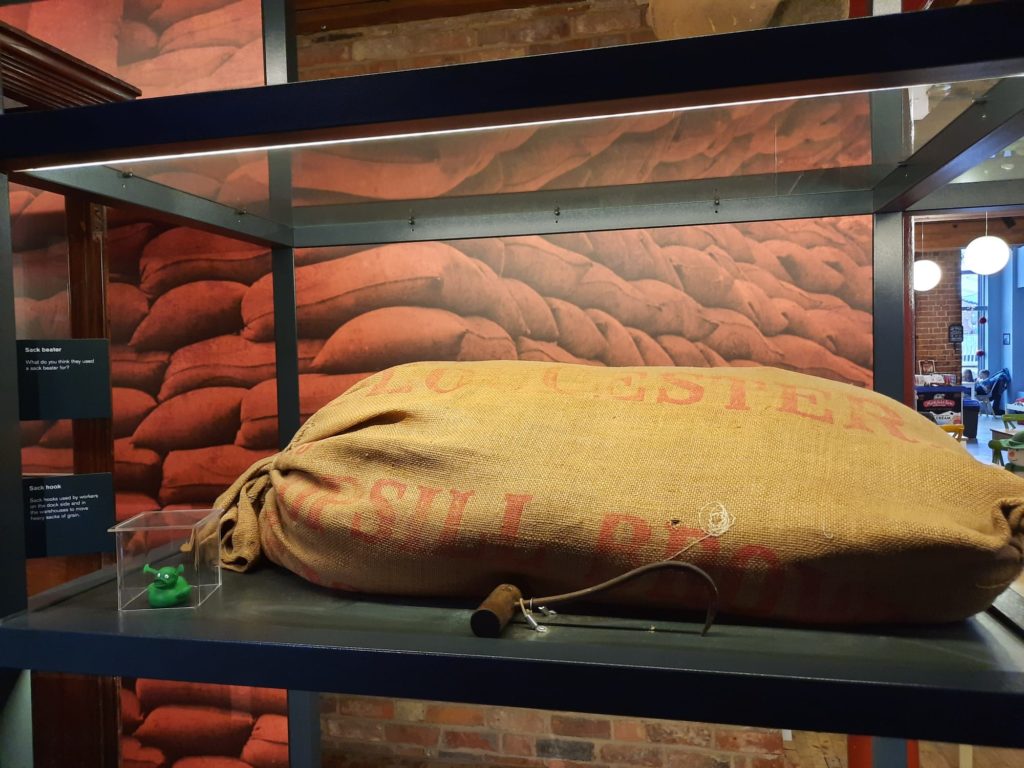

I think we are sufficiently prepared now to take a closer look at the museum itself. As I mentioned above, the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks is in Llanthony Warehouse. It doesn’t take up the entire warehouse, however. It’s over two out of six stories, with offices and archives on the other floors. Llanthony Warehouse, built in 1873 for local corn merchants Wait, James & Co., would have been used to store grain and maybe other goods like timber and alcohol. A 2016 refurbishment uncovered many original features, like the warehouse’s windows, original floors, and cast iron columns.

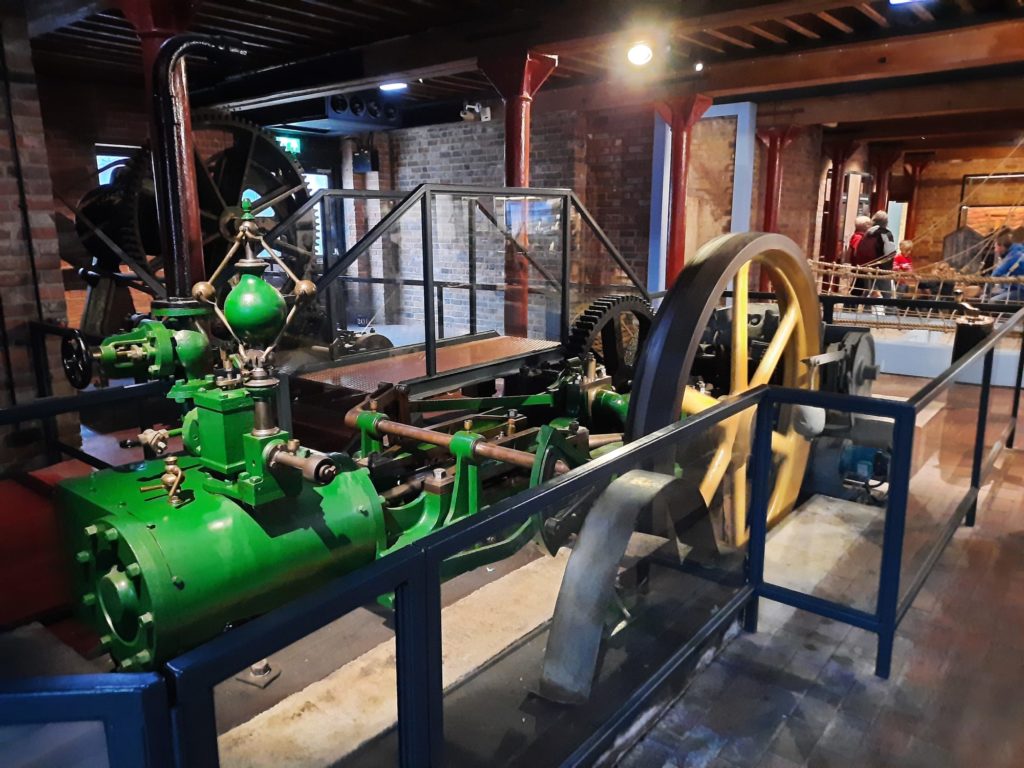

As a converted industrial space telling a story about commerce conducted over water, it feels very much like the Museum of London Docklands. I mean this in a multi-sensory capacity. There’s something about these old spaces and filling them with exhibits of sacks and machinery that produces a very evocative and immersive smell as well as the sights and sounds of a creaky old warehouse. Compared to the Museum of London Docklands, however, the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks has more exhibits in working order. There are some engines whirring away inside, while outside there’s a steam-powered dredger and other machinery as part of a simulated canal repair yard. In some ways it makes the history feel much more immediate. In others, it shows the challenge of conserving waterways history as bits of rust and rot are in evidence.

Objects, Stories And Interactive Exhibits

The museum is fairly object-led, but supplemented with interactive exhibits and personal stories. So next to some of the tools used to haul goods on and off boats, little ones can have a go at winching toy blocks. Or the bigger kids can try their hand at balancing a load. I love a museum interactive so of course did both. Upstairs, there are video interviews with several men who once worked in or around Gloucester Docks. They tell us a little about their jobs, but also the lifestyle that came with it. There’s understandably a fair bit of nostalgia for a world that has now disappeared. The preservation of these oral histories is a laudable project as well as providing an interesting display.

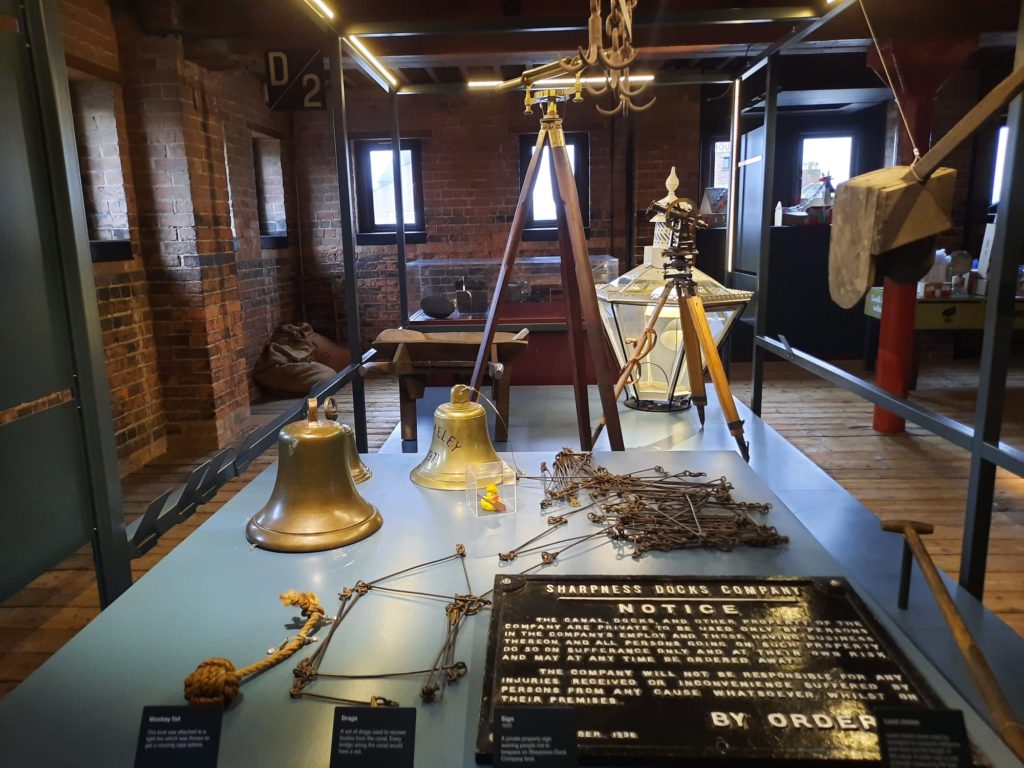

In some ways the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks also reminded me of my visit to the Thames River Police Museum. There’s something about objects that are so commonplace until they’re not, and you find the last one forgotten in a corner or a cupboard and musealise it. Both museums are full of these worn, everyday objects that tell a story of hard work and technological change. The process fascinates me: if you went back and found a 19th century navvy and told him his equipment was carefully preserved in a museum, he wouldn’t know what you were on about.

And really that’s what this museum does well. It preserves stories which were once everyday, common place, working class. Lives that were unremarkable and jobs that were taken for granted. And reminds us that things can change pretty quickly, and we don’t always know what’s around the corner. If we can have fun while learning this, imagine ourselves for a moment as the people living or working on the waterways, then even better.

Final Thoughts On The Museum

Whether or not this is a national museum is really beside the point at the end of the day. The National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks preserves a local version of a nationally important story. It contextualises today’s shopping and restaurant district by reminding us of its origins in a very different type of commerce. And it gives us the opportunity to see what purpose all these towering warehouse buildings once served.

The museum is great for families. There are plenty of interactives, including the ones I’ve mentioned plus a few more. It’s probably better in this respect than London’s Canal Museum, which I remember being more information-heavy. But it’s also interesting for adults, with lots of good static and interactive content to get to grips with.

To bring us back to our original conundrum, unlike many national museums, this one isn’t free. But an entry ticket covers a year’s visits, so is great for locals or frequent visitors. I saw my ticket as an investment in the not inconsiderable upkeep of this historic building and its contents. A small note on timing to finish with. I visited in November, which on the one hand is nice because Gloucester Docks does a good Christmas market. But on the other hand I suspect that the museum has a better programme of events in the warmer months. Otherwise that outdoor area with all its machinery and infrastructure really would go to waste. Something to bear in mind if you’re planning your own trip: look ahead on their website to see what’s on.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.