Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In – National Portrait Gallery, London

The National Portrait Gallery‘s exhibition juxtaposing two pioneering female photographers, Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In creates a curious tension in which the pairing both makes sense and doesn’t. Read on to discover why.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron

Francesca Woodman. Julia Margaret Cameron. Do you recognise the names? I recognised one and not the other before visiting this exhibition, so let me assume something similar for you and tell you a little about them.

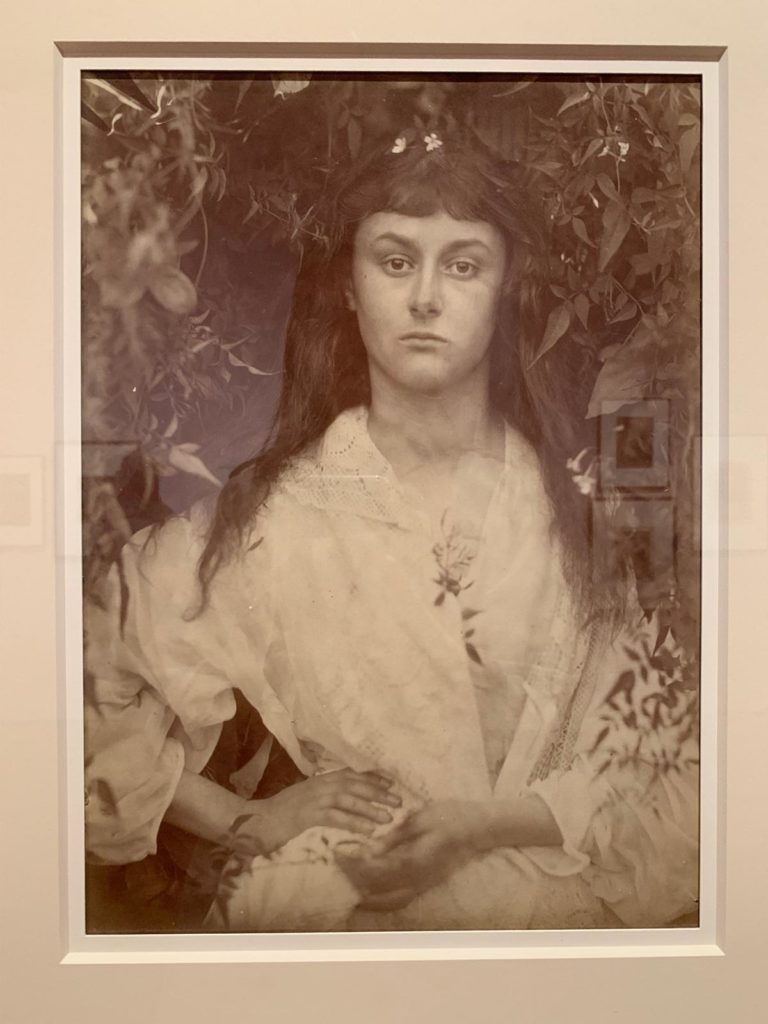

One (Cameron) was a pioneering Victorian photographer. Born in 1815 in Calcutta, she took up photography aged 48 after receiving a camera as a gift. She moved in influential circles, including running her own literary salon on the Isle of Wight. Because of this, her work is a mix of portraits of artists, scientists and other well-known people, and experimental works in which she played with early photography’s potential.

The other (Woodman) was born in Colorado almost 150 years after Cameron, in 1958. Her parents were artists, and Woodman showed a precocious talent. Her work was experimental (in a different way than Cameron’s with another 150 years of technology and art history to drawn on), but a perceived lack of recognition contributed to Woodman’s poor mental health, and she died by suicide in 1981.

Similarities and differences, then. Both female photographers, working mostly with the human figure. Both experimental in terms of technique and composition. Living in very different periods, different countries, and taking up photography at different life stages. Different backgrounds, but both with a path to establish a legacy (in Cameron’s case her social standing, in Woodman’s her parents’ careful curation of her estate).

Portraits to Dream In

Beyond these superficial comparisons, then, why bring these two artists together? Well, curator Magdalene Keaney works hard to draw a few parallels. She starts with the exhibition title: Portraits to Dream In. It was Woodman who said that photographs could be “places for the viewer to dream in”, and the exhibition, according to the introductory text, “explores the idea that both conjure a dream state within their work as part of their shared exploration of appearance, identity, the muse, gender and archetypes.”

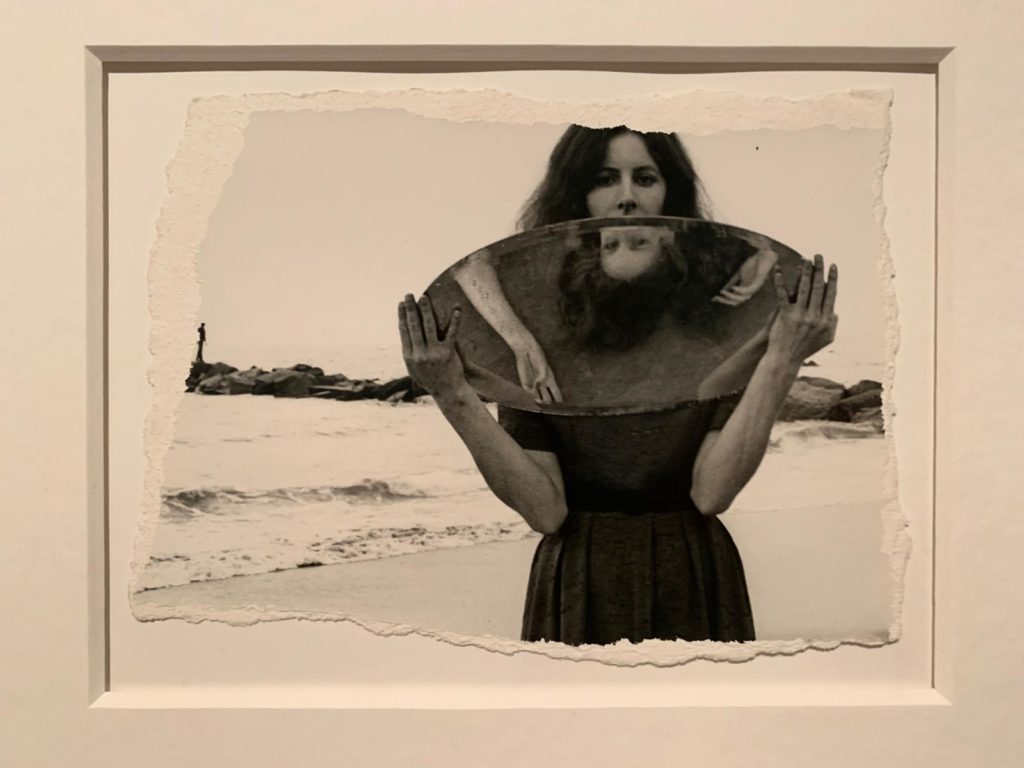

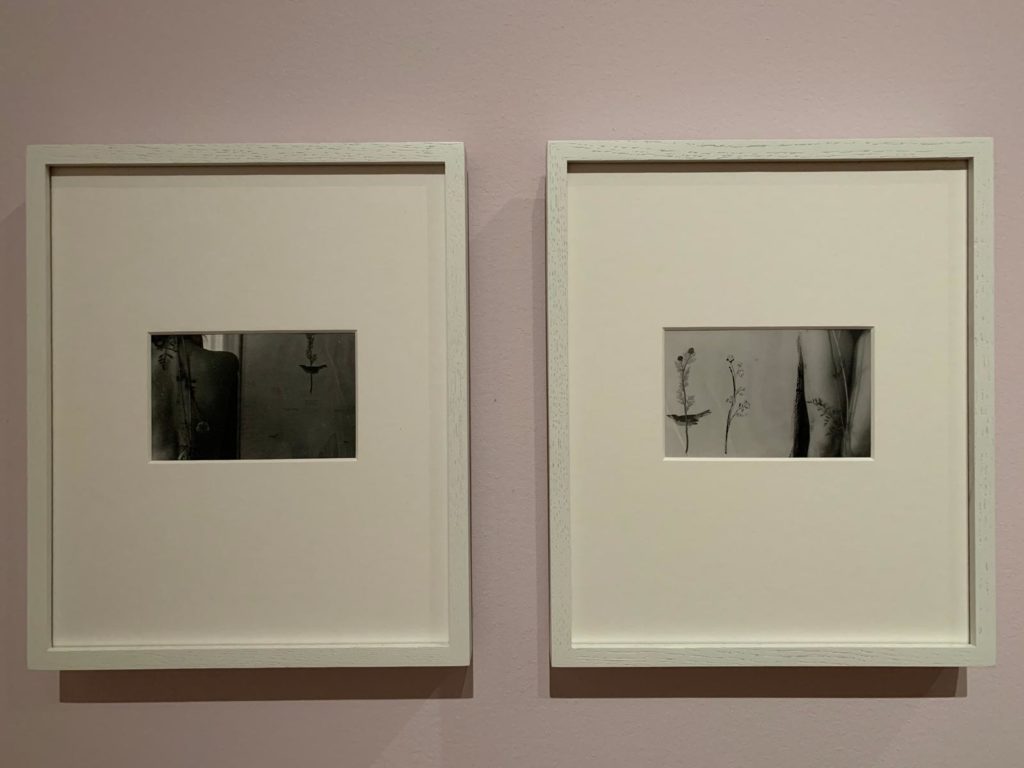

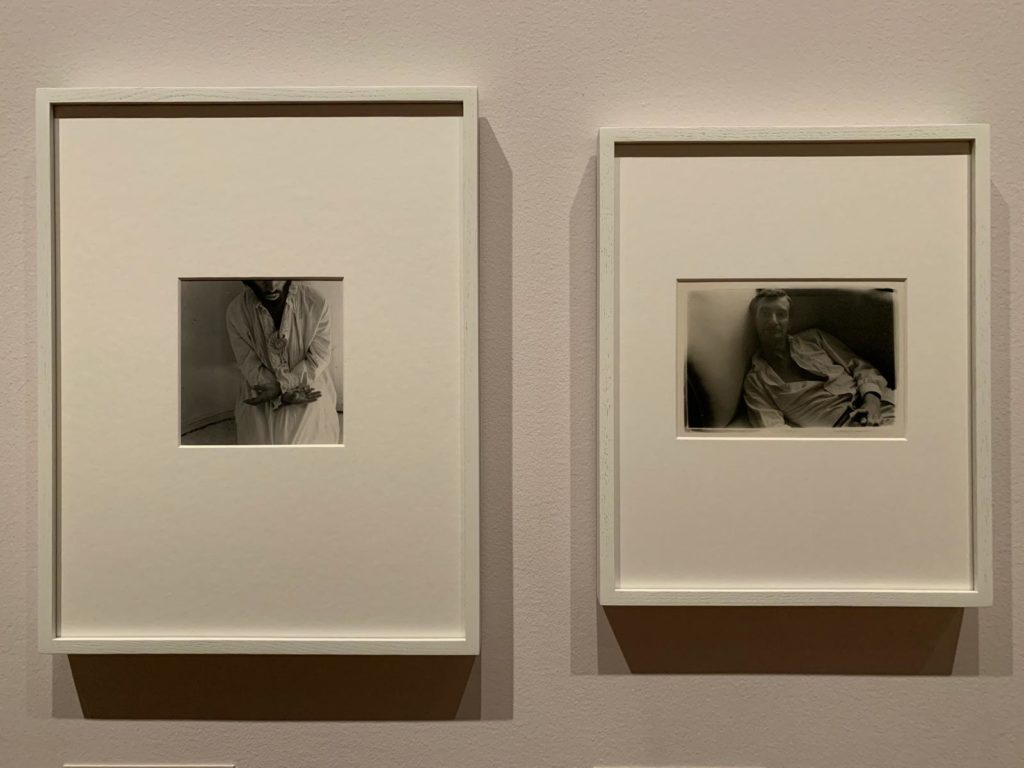

But what does that actually mean? Well, the exhibition blends vintage prints by both artists. Sometimes this means hanging one work by each woman side by side, sometimes juxtaposing groups of works by each. Keaney has done this around themes. Similarities of intention (claiming space), technique (embracing imperfection), subject (mythology, classical sculpture, angels, nature and femininity), sitters (favourite faces, their depictions of men) hang together. There’s a very sharp eye at work here: Woodman never declared Cameron’s work as an influence to my knowledge, but some of her shots seem to be responses to the earlier works.

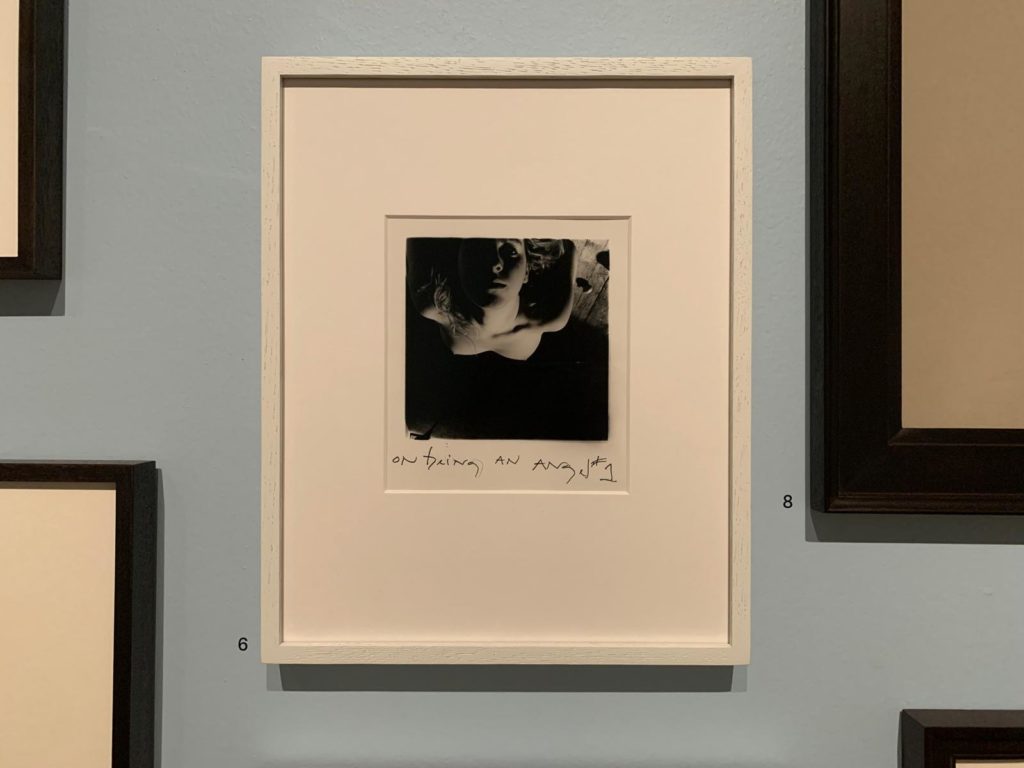

Similarities don’t mean an identical approach, however. While Cameron took depictions of angels very literally, for instance (her images are almost the Anne Geddes of her day in how sweetly the children are depicted), Woodman comes at it obliquely. Sometimes traditional signifiers of heavenly beings are there, sometimes they are not. There is more room for interpretation and I found her pictures more interesting as a result. But I guess that is the difference between being pioneering because you’re at the forefront of an entirely new medium, and being pioneering because you’re pushing the boundaries of an established art form.

The Tension Inherent in Comparison

Expanding on this a little, there were points at which I thought the comparison between the two worked, and points where it didn’t. Also points where it worked in favour of one artist, then the other. To start with, Cameron’s work is so pioneering that to us it sometimes doesn’t feel that exciting. Although her work was bold and experimental at the time, she likely wouldn’t even recognise art photography today. Woodman’s compositions and techniques, with the luxury of an additional century, are by far the more interesting of the two.

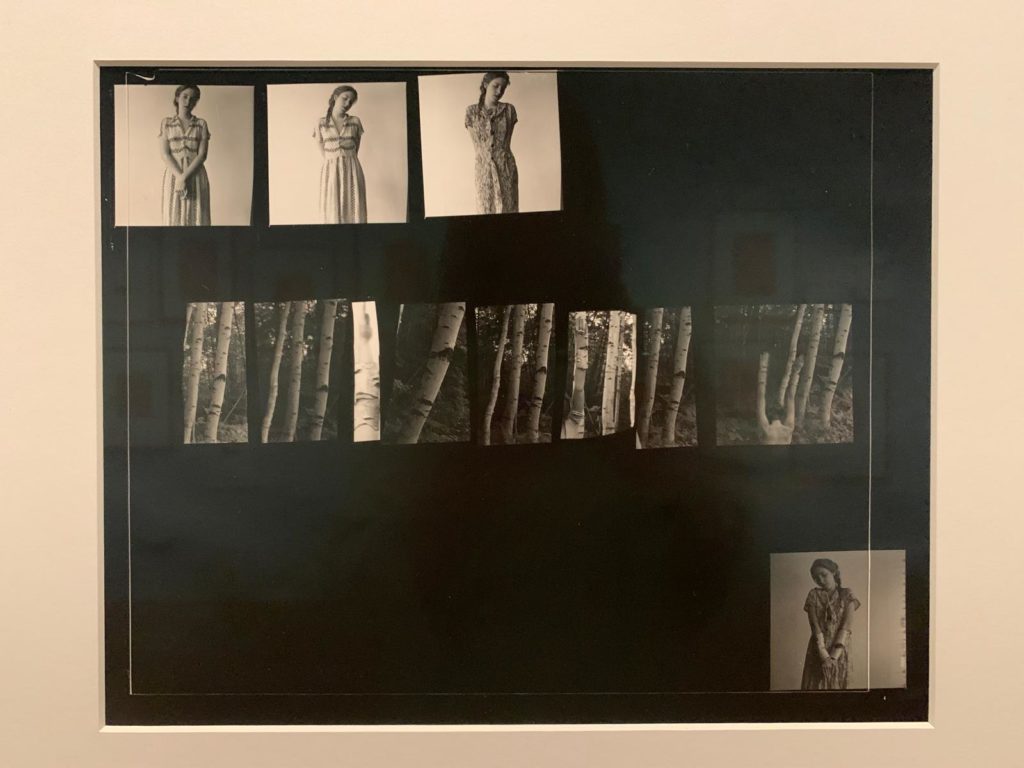

Woodman sometimes suffers by the use of vintage prints, however. Albumen prints (made with egg white) were often larger-format than the handheld cameras Woodman used. So Cameron’s works jump out, while you have to get up close to appreciate Woodman’s. This isn’t always the case: the biggest works of all are Woodman’s diazotype prints of herself as a caryatid. But it’s easy for her smaller works to be swamped by Cameron’s larger, sepia-tinted prints.

Finally, the Venn diagram Keaney draws between the two artists sometimes feels a little tenuous. The mythology section, for instance. Cameron mostly titled her works, so we know exactly what she was depicting. Woodman did not. So while we know Cameron’s young woman with a small spray of flowers is a nod to Daphne, who turned into a laurel tree, Woodman’s self-portraits during a residency in New Hampshire feel more like a response to her own body in the natural world. The comparison thus feels more forced than some of the others.

Final Thoughts on Portraits to Dream In

Despite these few critiques, on the whole I enjoyed Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In. It’s a reasonably scholarly topic but, per the National Portrait Gallery’s new style guide, presented in a straightforward and easy to understand way. And ultimately I think juxtaposing the work of these two artists helps to bring Woodman to a wider audience. Many of the works here have not been shown in the UK before, and her photographs were a discovery for me. Cameron I’m much more familiar with.

This was also my first visit to the National Portrait Gallery since it reopened in June 2023 (OK I’m a bit behind, apologies). I like the big new entrance around the corner from the old one. And I now want to go back and see how they’ve rehung the permanent collection. The exhibition space itself is not well sign-posted from the lifts, but is functional and a good size. I had wanted to see The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure, but events conspired against me so I’ll have to wait a bit longer to see the main exhibition space. But as a first foray into the NPG, I think we can count this a success!

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In on until 16 June 2024

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.