The Last Caravaggio – National Gallery, London

An exhibition of just two paintings and a letter, The Last Caravaggio illuminates interesting biographical and artistic details from the master of light and shade.

The Last Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio died as he lived. Chaotically, brashly and a little unpleasantly. He’s the poster boy (well, among others…) for the debate over whether we should take into account a person’s deeds and morals or just judge their art on its own merits. On the one hand, his paintings still impress us with their light and shade, spawning the adjective caravaggesque. He had a huge influence on later artists. And has a secure spot in the art history canon largely thanks to art historian Roberto Longhi championing his importance. On the other hand, however, his drinking and fighting were legendary. He killed a man, went on the run, and died of an illness chasing down his lost possessions in 1610 at the age of 38, following confusion about whether or not he had a papal pardon. Great artist, seemingly not a great guy.

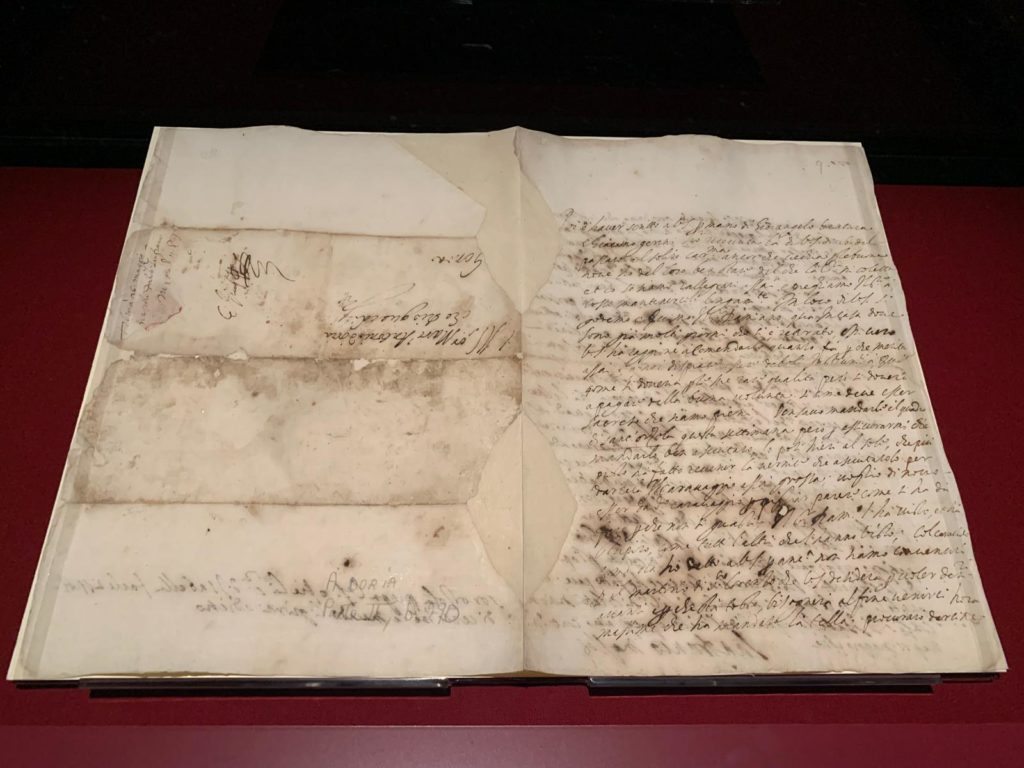

In earlier centuries, the seriousness of Caravaggio’s actions tarred his art with the same brush. Some of his paintings were misattributed to more wholesome artists, and he was largely forgotten. This has meant works have continued to come to light in recent decades. This is the case for both works on view in this small, free exhibition. Both the National Gallery‘s Salome Receives the Head of John the Baptist and The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula on loan from a bank collection in Italy were of uncertain provenance when purchased. Both are now firmly Caravaggios. The latter in fact the very last work Caravaggio painted, as confirmed in a letter also on display. The letter paints a real picture itself: Caravaggio rushing to finish a commission, and his business agent almost ruining it by putting it to dry in the sun and accidentally softening the varnish.

The Saint and the Sinner

With my tongue in cheek title for this section I refer not only to the artist and the subject of the ‘last Caravaggio’, but to the two women depicted in this exhibition. Heading around the room clockwise we first examine the National Gallery’s work. Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist. The reality of the saint’s severed head is confronting, Salome’s look of distaste unsurprising. The quality and finish of this work is superior, even if the composition of the other is more creative and the drama more immediate.

Do you know the story of Saint Ursula? The historic basis is uncertain. But the medieval legend has it that she (a princess) and 11,000 virgins experienced a miracle, went on a pilgrimage, and headed to a Cologne under seige by Huns. The leader of the Huns didn’t appreciate Ursula turning down his offer of marriage, and shot her with an arrow. For most artists, the possibilities of this story are immediate. 11,000 virgins! A beseiged city! A miraculous journey by sea! Most of the images I’ve seen of Saint Ursula are detailed affairs. Generally lots of ladies (I never count to see if all 11,000 are there) and bird’s-eye perspectives. Caravaggio’s is the polar opposite. Only six figures in total. Ursula is the only woman. Caravaggio brings the composition in incredibly close, so you feel like it could be your hand reaching out to try to stop the arrow.

It’s too late though, the Hun king’s arrow has pierced her breast, which she clutches in shock, grey and dying. Shock is the general feeling, including in Caravaggio’s self-portrait (the man at the back). The novel composition and the sheer emotion show why Caravaggio’s was a rare talent. But you have to wonder – if he wasn’t dashing this painting off just weeks before his death, would he have kept working on it? Is Ursula meant to look quite that grey? It’s unclear, but shows what our continued interest in Caravaggio shares with other talented people whose ‘live fast, die young’ approach to life prevented that talent being realised.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

The Last Caravaggio on until 21 July 2024

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.