Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence – V&A, London

The V&A present an exhibition on Tropical Modernism, a subject with a lot more to unpack than may meet the eye in terms of colonial and anti-/de-/postcolonial politics; internationalism and nationalism; past, present and future.

Tropical Modernism

As a person with interests in architecture, postcolonialism, and complex historical narratives, I have had Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence on my list to visit for some time. I finally overcame the inertia (not to say laziness) which often prevents me heading to West London of a weekend. And so it was with pleasure that I journeyed to the V&A for the first time in quite a while.

Just what is the complex historical narrative in this instance, though? And what is tropical modernism, anyway? As a starting point, let’s look at how the V&A introduce the exhibition:

“Tropical Modernism was Britain’s unique contribution to International Modernism – a colonial architecture, developed by British architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, against the background of anti-colonial struggle in India and West Africa in the late 1940s. This exhibition looks at the colonial origins of Tropical Modernism in British West Africa, and the survival of the style in the post-colonial period when it symbolised the independence and progressiveness of newly independent countries like India and Ghana.”

About the Tropical Modernism exhibition · V&A (vam.ac.uk)

Interesting questions thus start to arise. How can Britain, a decidedly un-tropical island, have contributed a tropical architectural style to the world? (OK that one’s easy: colonialism). How did modernist architectural principles apply in this context? Are we saying that the same architectural style represented both the colonisers and new-found independence? How? And if this style isn’t still in evidence today, what happened to it?

We’re in the right place to start answering some of those questions (or at least looking into them further). So let’s jump into the exhibition now.

What is Tropical Modernism?

Let’s go with the most obvious answer: it’s modernist architecture in a tropical setting. But why did modernism need to be adapted, and how are we defining modernism anyway? I will defer to RIBA here:

“Rejecting ornament and embracing minimalism, Modernism became the single most important new style or philosophy of architecture and design of the 20th century. It was associated with an analytical approach to the function of buildings, a strictly rational use of (often new) materials, structural innovation and the elimination of ornament.”

Modernism (architecture.com)

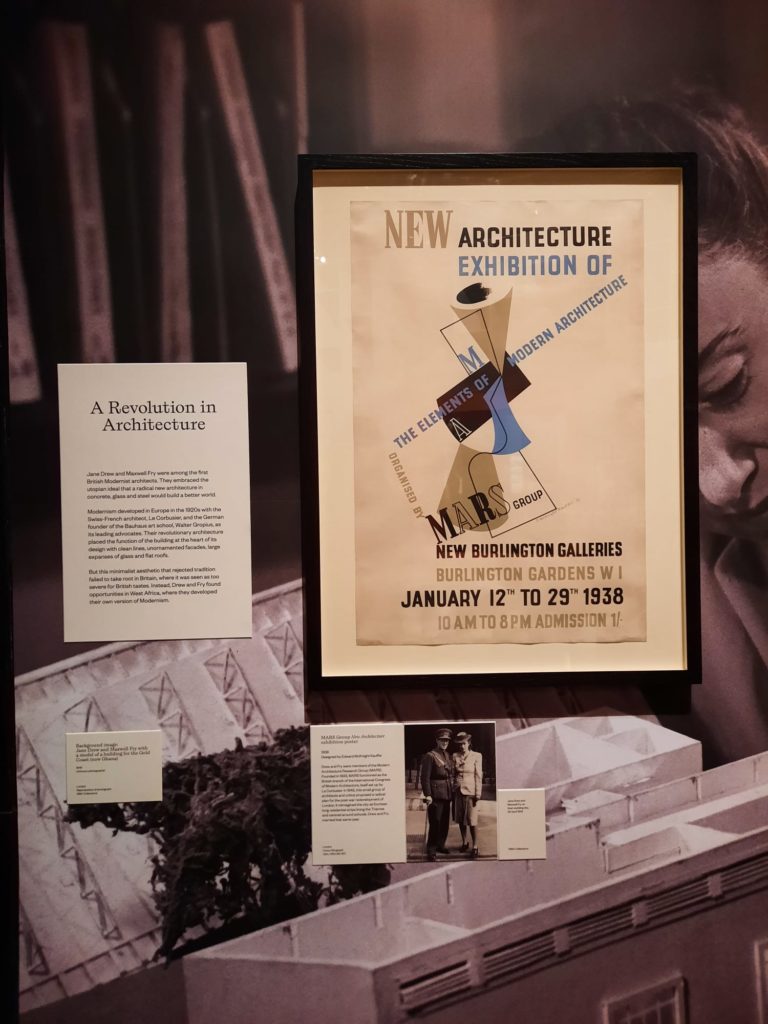

So concrete, glass, steel, a focus on clean horizontal lines. Think Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Frank Lloyd Wright. It was a very internationalist and utopian movement. The new building materials were signs of progress, and the lack of decoration meant a style that could work anywhere, beyond the confines of national(ist) boundaries and borders. At least in theory. It never really took off in Britain, though. There were some prominent modernist commissions, but it was never a force here like Germany’s Bauhaus, for instance. And actually a lot of the modernist buildings were the work of imported European architects like Berthold Lubetkin and Ernő Goldfinger.

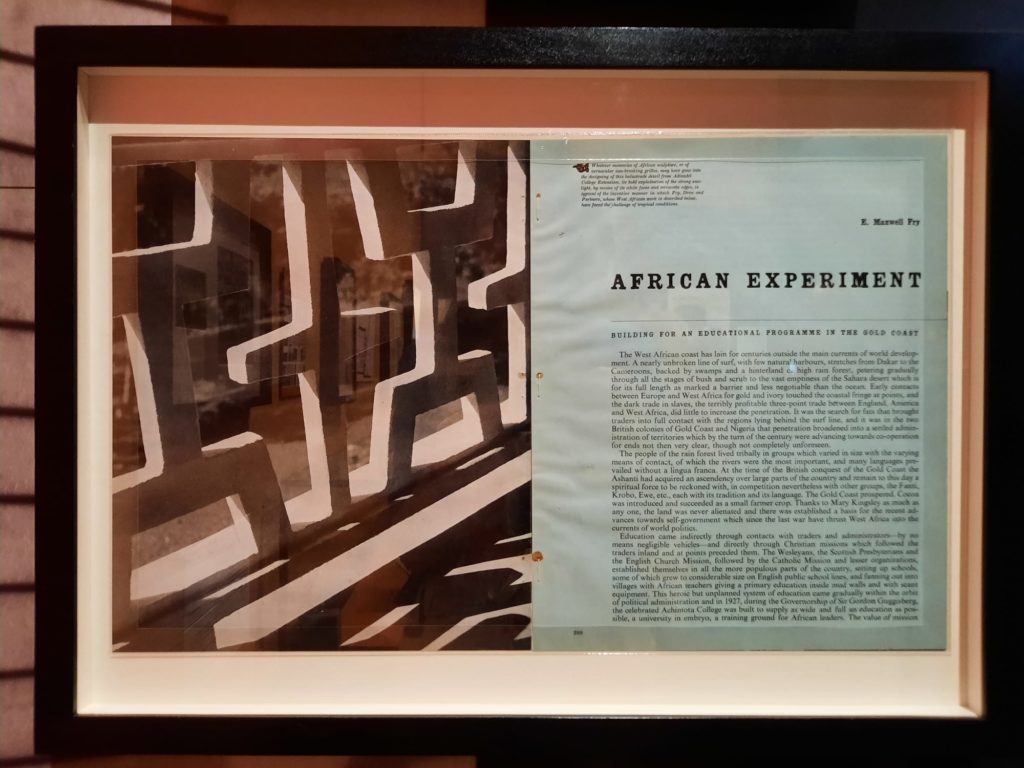

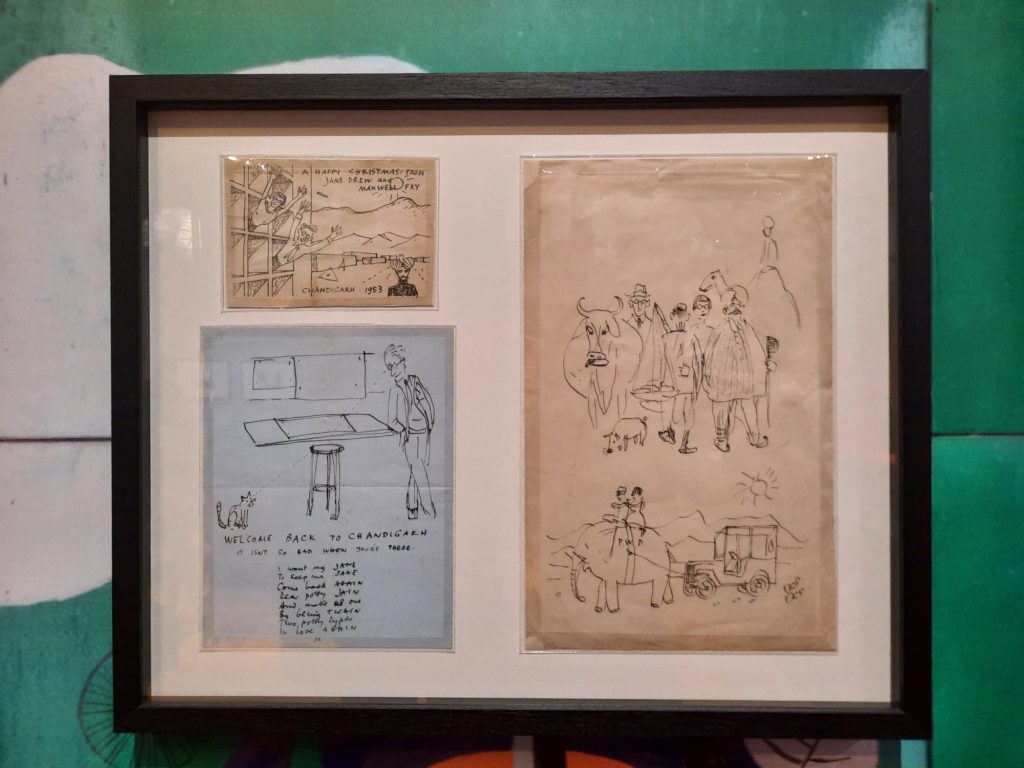

Not all modernist architectural talent was imported, however. Tropical Modernism focuses on husband and wife team Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew. Fry and Drew sharpened their modernist teeth at home, but encountered a lukewarm reception. By adapting the principles of modernism, however, they were able to seize on a much larger market: Britain’s then immense colonial territories. And thus tropical modernism was born.

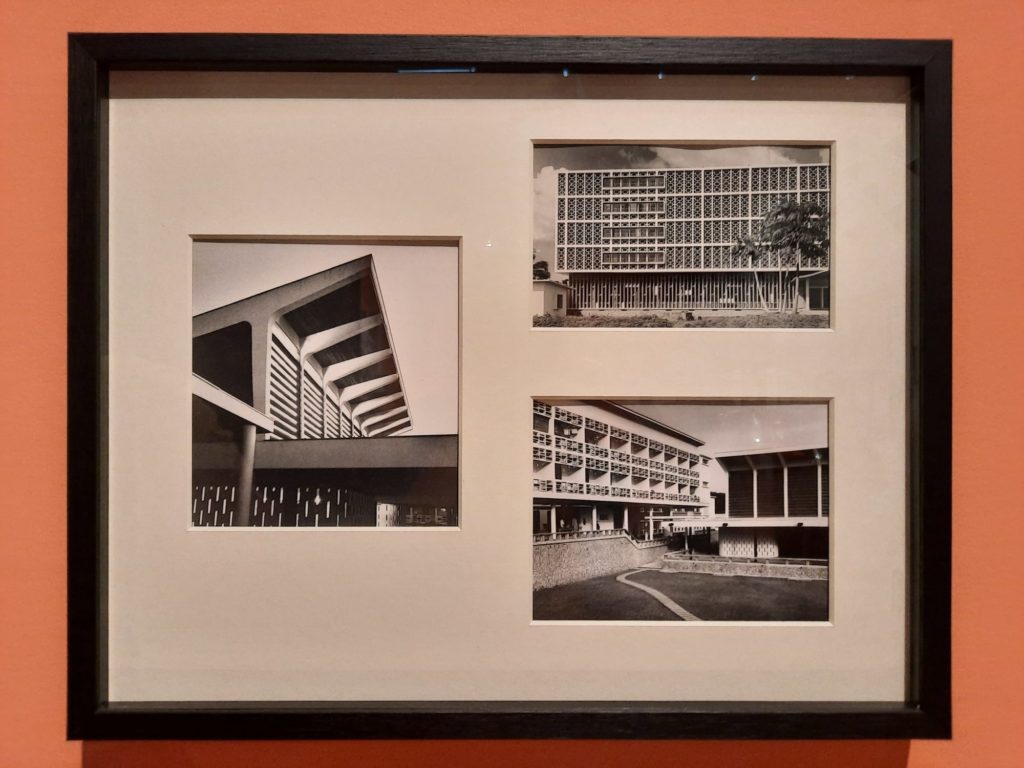

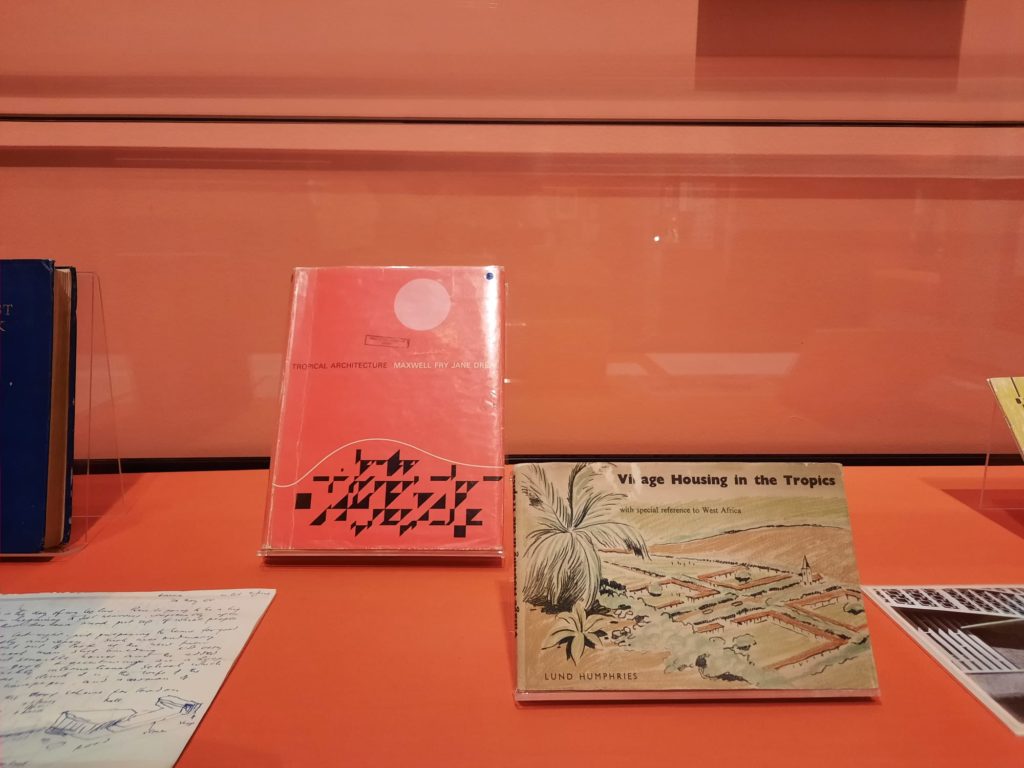

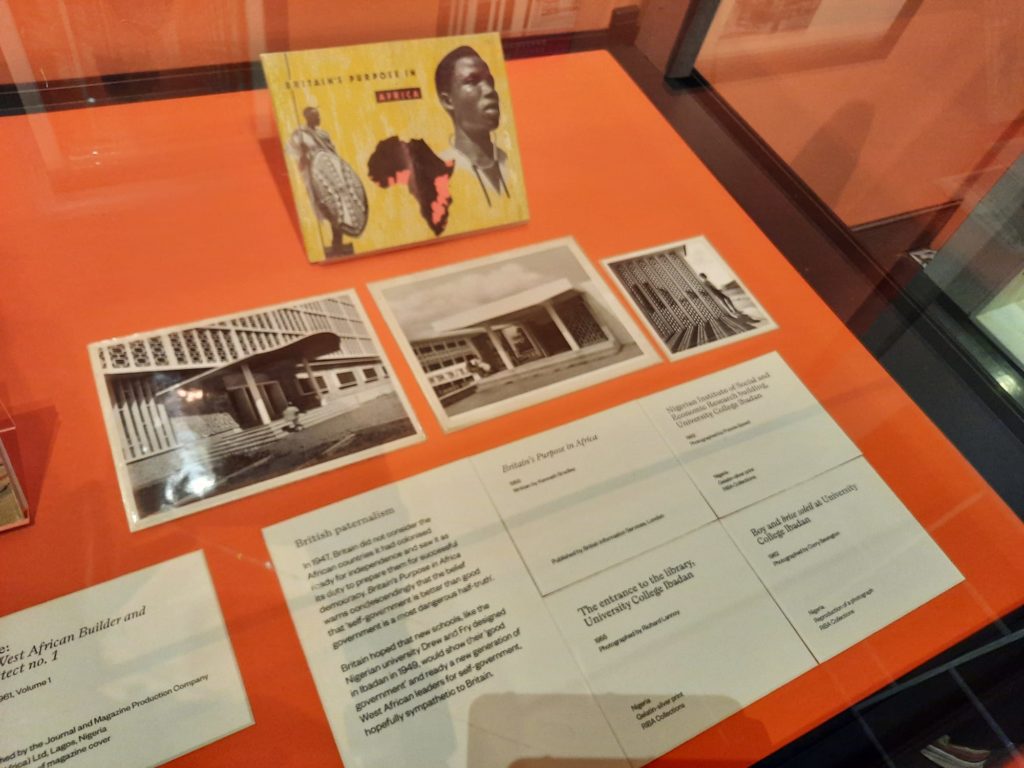

At the time, Britain was attempting to assuage calls for decolonisation from various quarters. One strategy was to invest large sums in local community, cultural and above all infrastructure and educational projects. Fry and Drew researched and developed an architecture suited to this climate and this mission, with a focus on passive cooling, ventilation and shade. The levels of investment meant there was the possibility to experiment, and over time tropical modernism became a topic of research, publication and teaching.

Less of the Colonial Lens, Please

So far we’ve fallen somewhat foul of the trap of discussing the colonisers and not the colonised. Let’s begin to redress that, shall we? Tropical Modernism takes two case studies: Ghana and India. Anyone with a vague architectural interest is probably familiar with Le Corbusier’s work in Chandigarh. I was less familiar with modernism in Ghana as, I imagine, are many others.

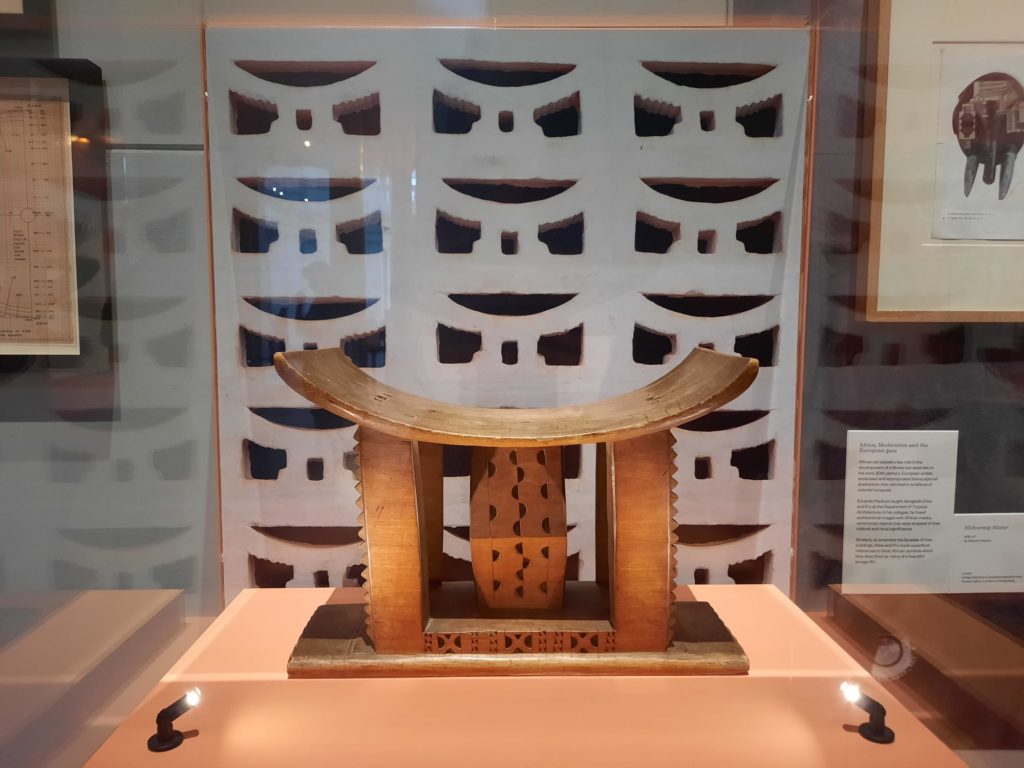

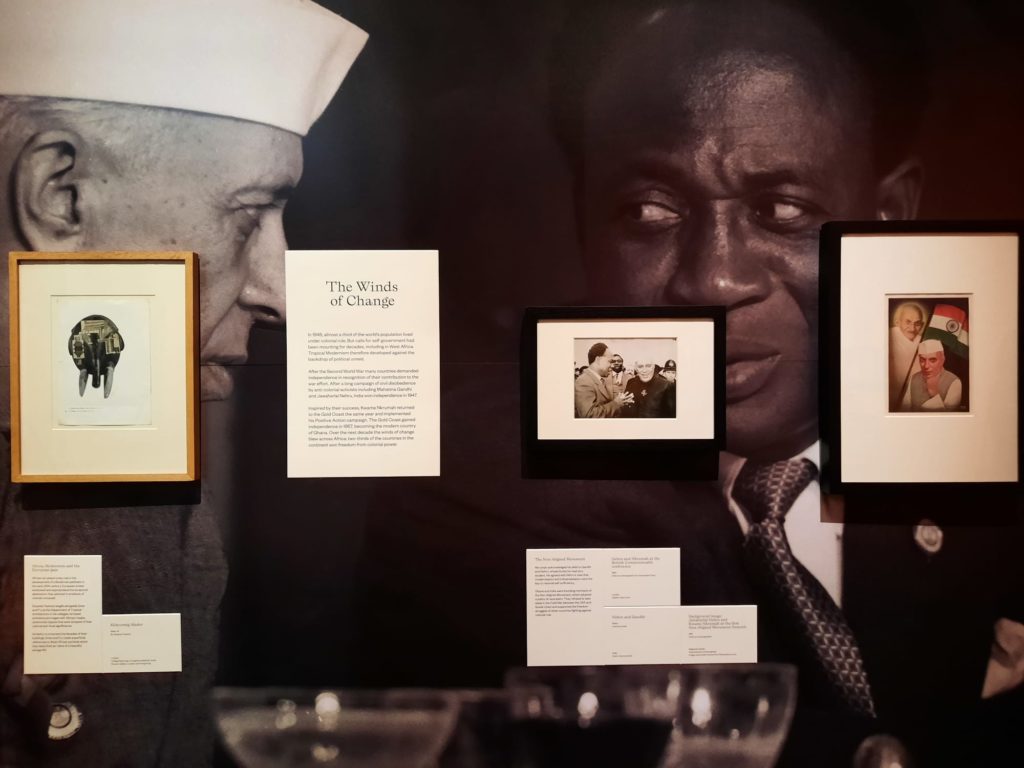

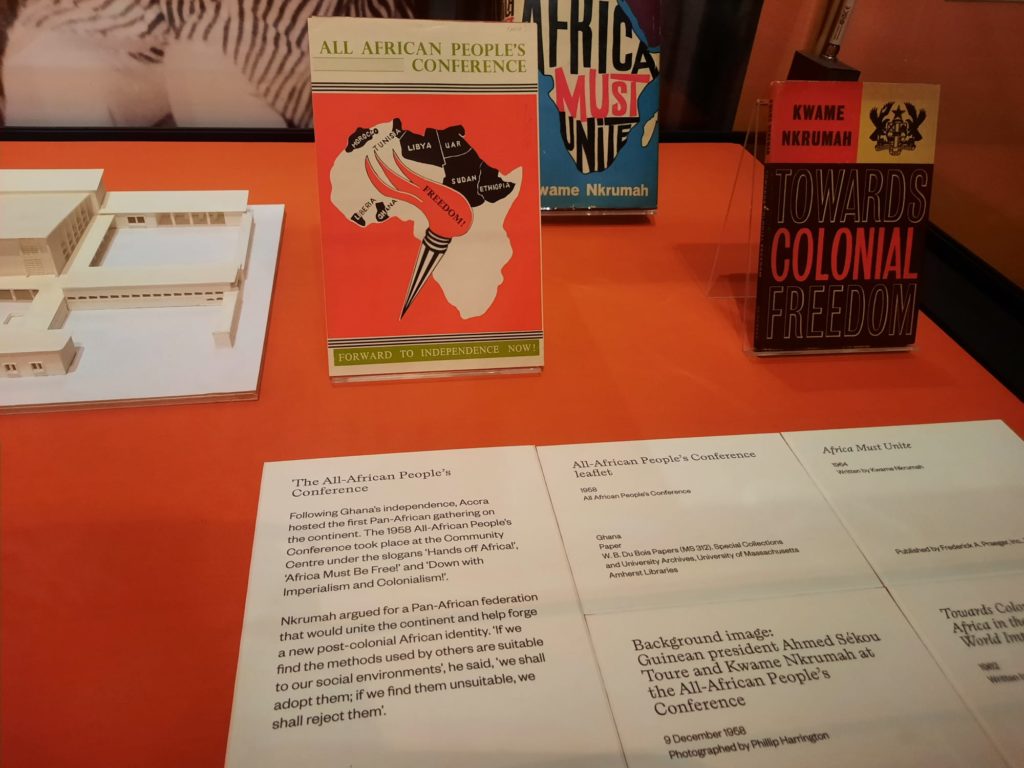

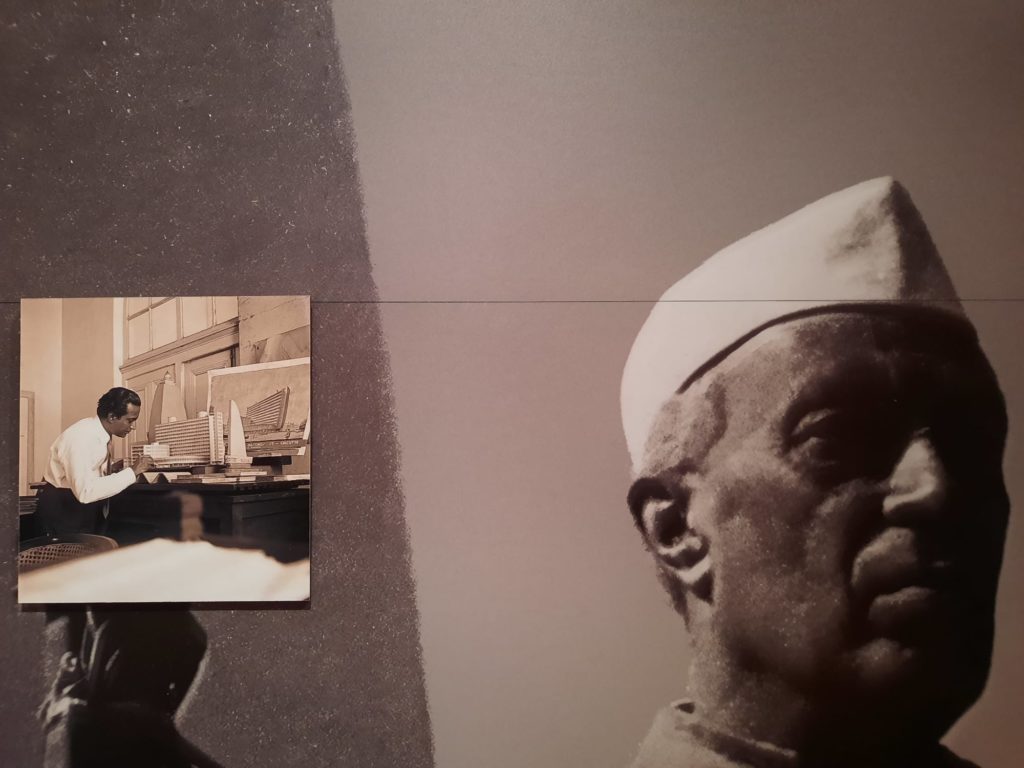

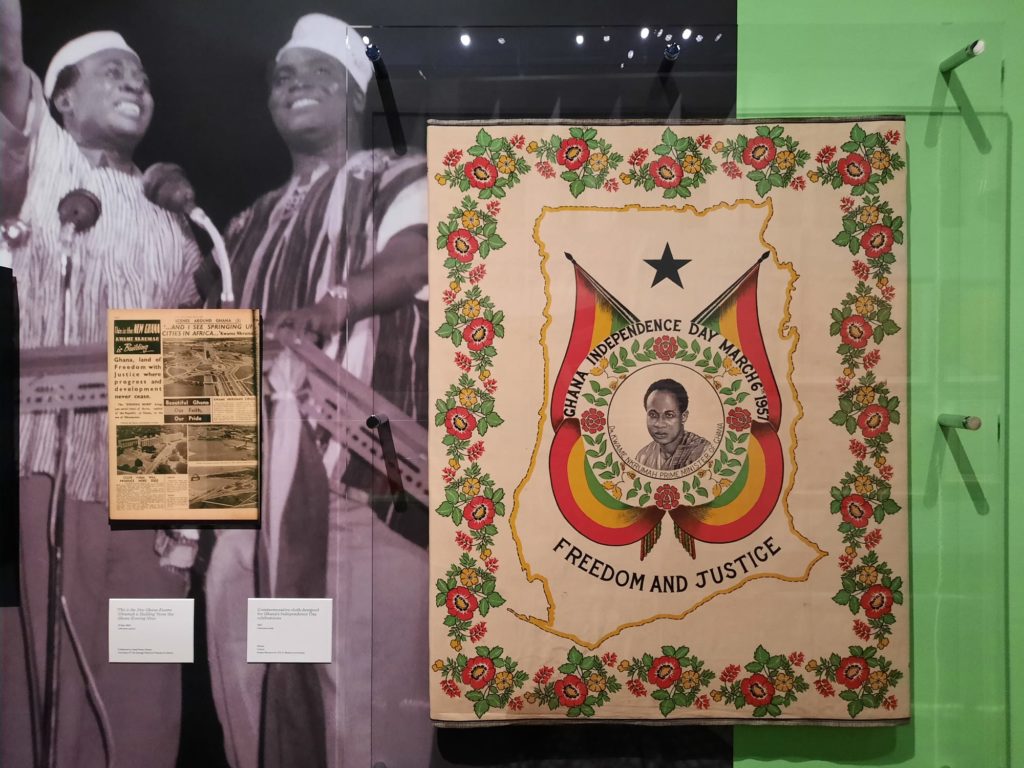

After an introduction to tropical modernism similar to what we’ve just done, the exhibition looks at some of the local personalities. The struggle for independence involved many big names: Jawarhalal Nehru, independent India’s first Prime Minister, being one. In Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah followed a similar path from critic of colonialism to politician. This first section of the exhibition introduces these figures and other topics through a mix of primary and reproduction printed materials and explanatory texts. Savvy visitors will also realise that the exhibition design echoes key principles of tropical modernist architecture, allowing partial views and flow between spaces.

We then move on to look at India and then Ghana in more detail. When it comes to India, Chandigarh is the primary focus. While a lot of discussion is necessarily of Drew, Fry, Le Corbusier and other Western architects, what begins to come through is what modernism meant to the Nehrus and Nkrumahs of the world. They embraced it, leaning into its internationalism and sense of progress to embody the excitement and hope of young nations.

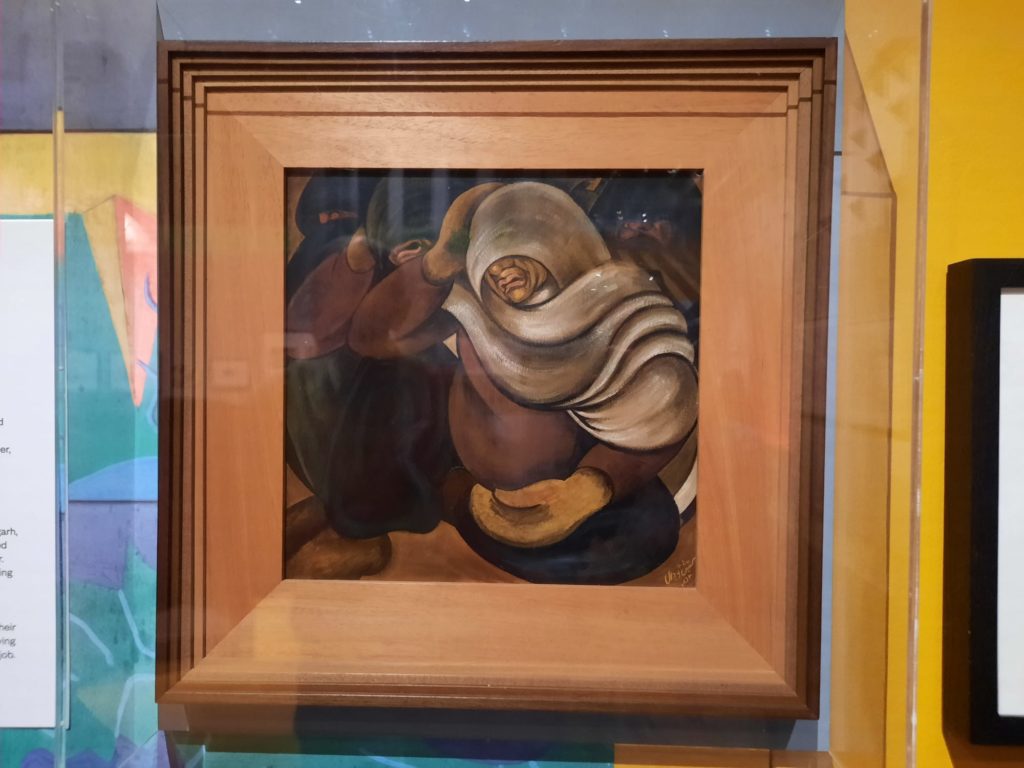

An interesting story begins to emerge of cross-cultural exchange. In both India and Ghana, architectural projects could only be undertaken with local architects either supporting or leading. The idea was clearly for foreign assistance to be temporary, and for local talent to grow. The star nature of some of the architects overshadowed local contributions, however: the exhibition rehabilitates Eulie Chowdhury‘s input into designs formerly attributed only to Pierre Jeanneret, for instance. There’s also an undercurrent of resistance. Tropical Modernism made little real effort to understand and incorporate a sense of place into designs. Nek Chand, a road inspector who built a secret garden of 2,000 sculptures from discarded building materials in Chandigarh, here symbolises a desire for idiosyncrasy and freedom against the facelessness and structure of modernism.

Where Did it All Go Wrong?

And so as you may have guessed, tropical modernism contained within it the seeds of its own destruction. As both India and Ghana matured in their independence, the reliance on modernist architecture became less and less attractive. Opponents of those early political leaders came to see it not as an international style but as a colonial one. In the case of Ghana, there is a very clear correlation between the rise and fall of Nkrumah and modernist building projects. Nkrumah was ousted in 1966: today some modernist buildings remain in use while others decay, but new projects certainly tapered off from this point. A damaged statue of Nkrumah watches over the final room in the exhibition where an excellent short documentary is screened. It’s worth a watch to put things into a contemporary context.

I didn’t realise when visiting the exhibition that it came out of a research project by London-based architects and educators Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Bushra Mohamed, with V&A curators Christopher Turner and Justine Sambrook. Or that an earlier iteration was part of the Venice Biennale in 2023. It explains why the exhibition is information-heavy. I actually looked for a catalogue in the shop after visiting because I couldn’t take it all in at once and wanted to read at my leisure. But strangely, there isn’t one.

Overall, this is an interesting and multi-faceted exhibition. It raises far more questions than could be answered within a few rooms. But I appreciated the challenge to really notice the architecture of this period, and really think about the different lenses through which it can be understood. I also appreciated the effort to bring together a good range of objects as well as all the important text-based sources. I would just suggest that you don’t visit this one if you’re already tired or hungry as you need to take your time and concentrate to get the most out of it. To take a quote from the Venice Biennale exhibition which I think applies here too:

“This exhibition presents an important moment in centering African architecture, architects, and historians, and addressing the omissions and erasure evident in the archives.“

La Biennale di Venezia 2023 · V&A (vam.ac.uk)

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence on until 22 September 2024