Judy Chicago: Revelations – Serpentine Gallery, London

The Serpentine’s exhibition on Judy Chicago focuses on a hitherto unpublished manuscript, perhaps to the detriment of the artist’s wider oeuvre.

Judy Chicago

Perhaps a little sooner than planned (there was a theatre scheduling incident, don’t ask), I am back to tell you about the other summer exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery. The last one, if you missed it, was Yinka Shonibare CBE: Suspended States at Serpentine South Gallery. This time we’re at Serpentine North Gallery, where we previously saw photography by James Barnor. But the subject under discussion today is one Judy Chicago.

Chicago, if you’re not familiar with her, is a first-wave feminist artist. Born Judy Cohen in Chicago in 1939, her parents May and Arthur were, respectively, a former dancer and a labour organiser and postal worker descended from a long line of rabbis. Chicago knew from a very young age that she wanted to be an artist. She took classes from childhood at the Art Institute of Chicago, but failed to gain entrance to their degree programme and went instead to UCLA. It was there she met her first husband, Jerry Gerowitz. The couple lived in LA, New York and Chicago before Gerowitz died in a car crash in 1963. After this traumatic death and the earlier death of her father, Chicago decided to eschew the patriarchal convention of a surname associated with a father or husband, and chose her own surname in 1970. Ironically, her second husband had to sign off on the change.

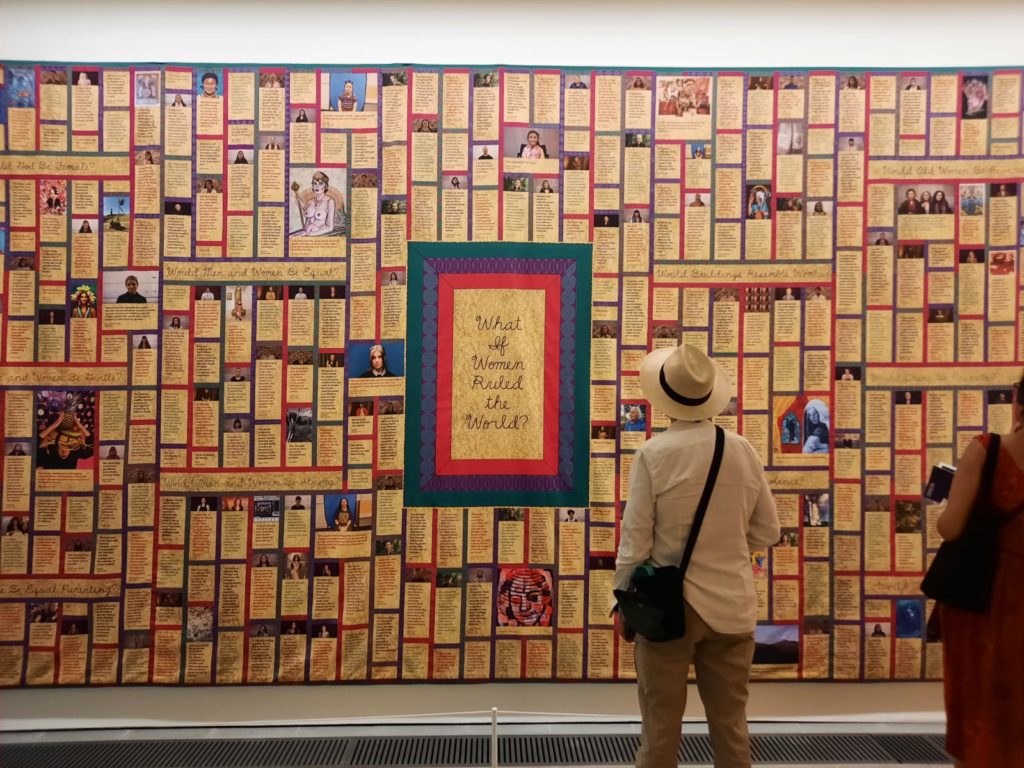

But enough of men. Chicago began to be politically engaged from her college days, but this was not initially reflected in her art. Looking back, she describes her minimalist work as attempting to fit into a boys’ club. Also in 1970 Chicago began teaching at Fresno State College (now California State University, Fresno). She set up the first feminist art programme in the US there. Over the following years Chicago blended teaching with her own art practice. She has worked in many media, including drawing, printmaking, painting, embroidery, land art, performance art, welding, sculpture, china painting, and more. Her work is held in many major museum collections globally. And now, at 85, this is her largest London exhibition to date.

Revelations

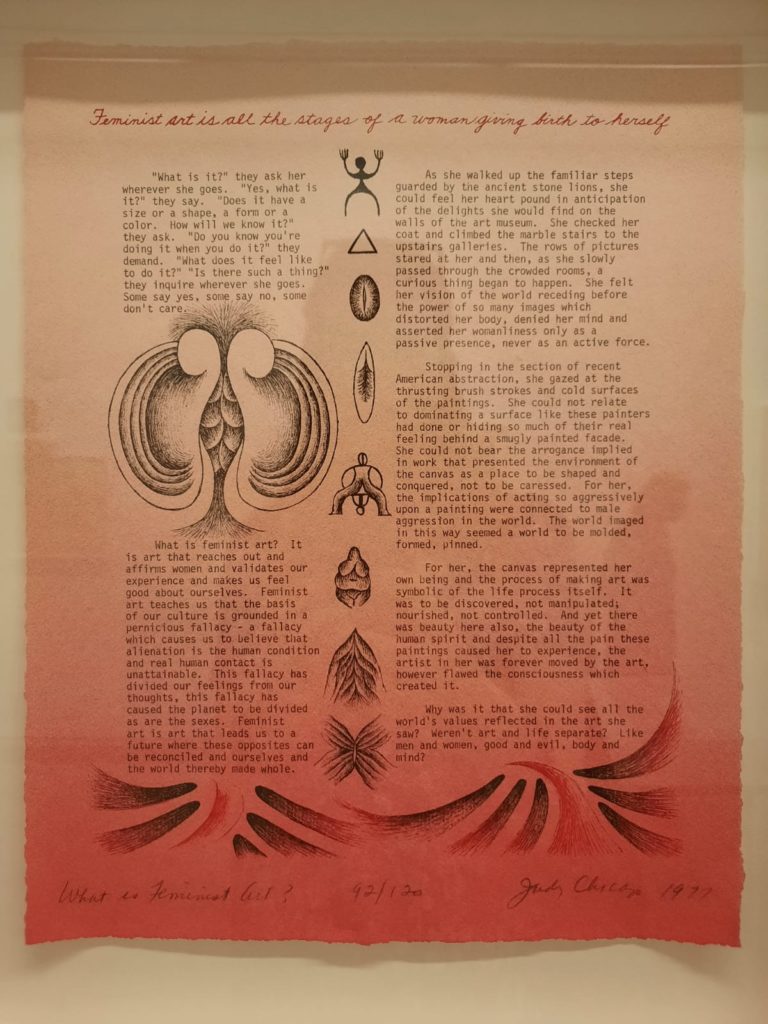

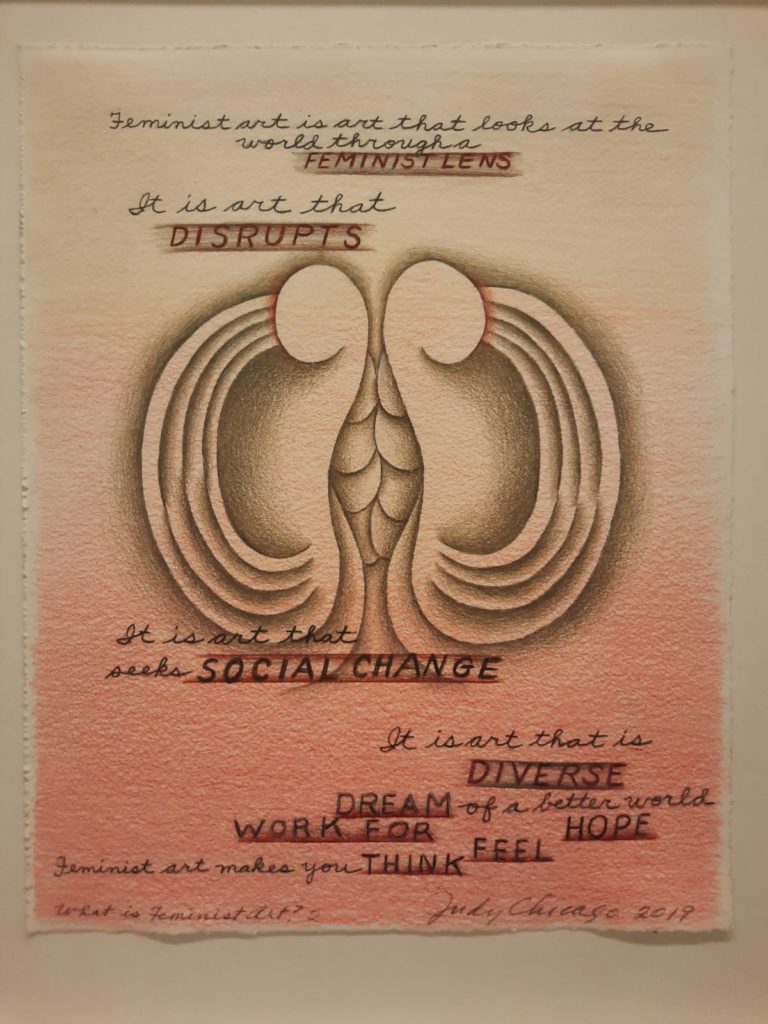

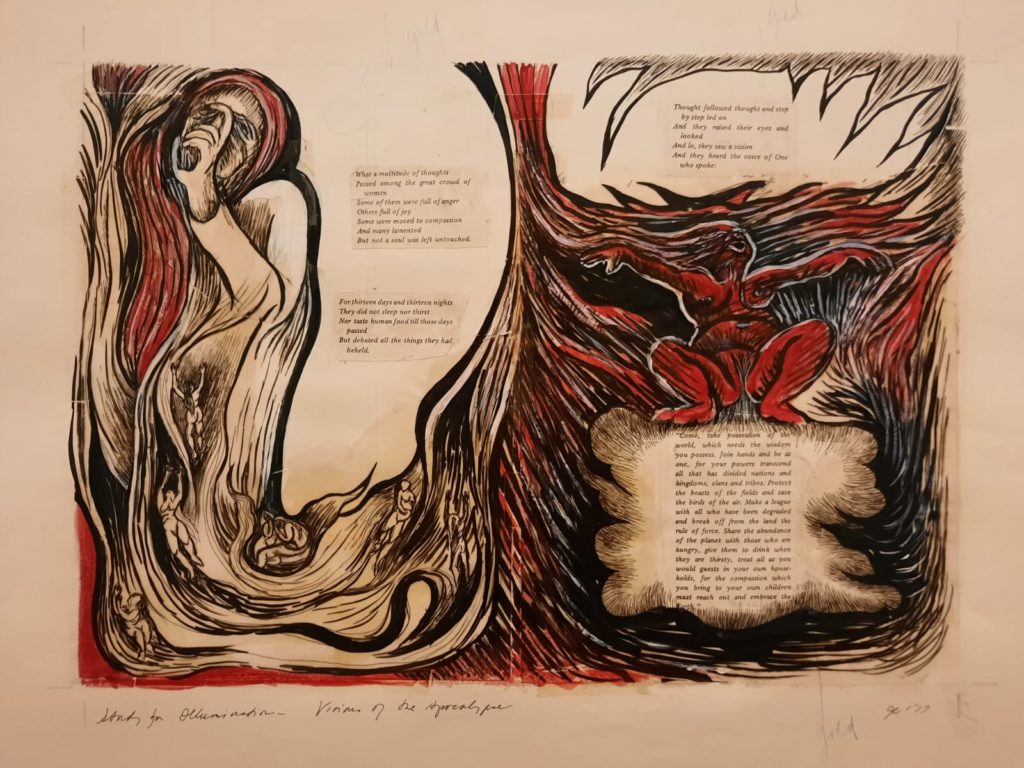

The title of this exhibition, Revelations, comes from a hitherto unpublished manuscript. Chicago penned it while working on The Dinner Party (1974–79), one of her most famous works now on permanent view at the Brooklyn Museum. The Dinner Party commemorates and symbolises the achievements of 1,038 women from history and mythology. Revelations stems from an encounter with a ‘radical nun’, and reworks the Genesis story from a feminist viewpoint. It draws on Chicago’s research into goddess worship and women’s history, and dreams of a just and equitable world. The manuscript, now updated and supplemented, has been published for the first time to coincide with this exhibition.

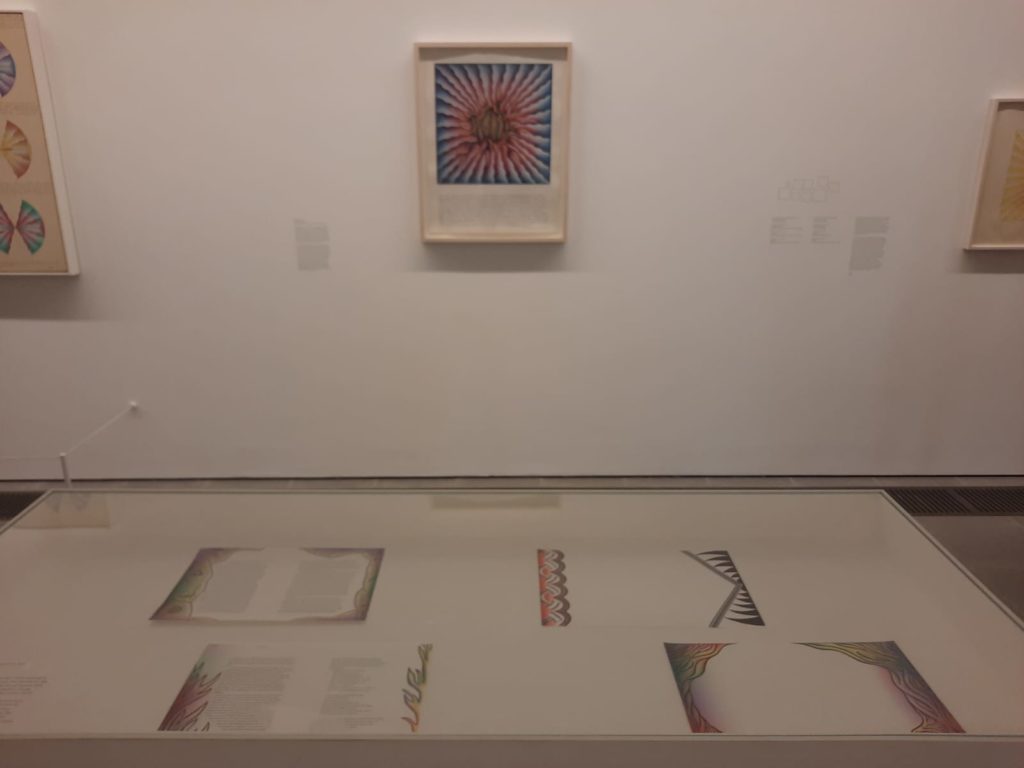

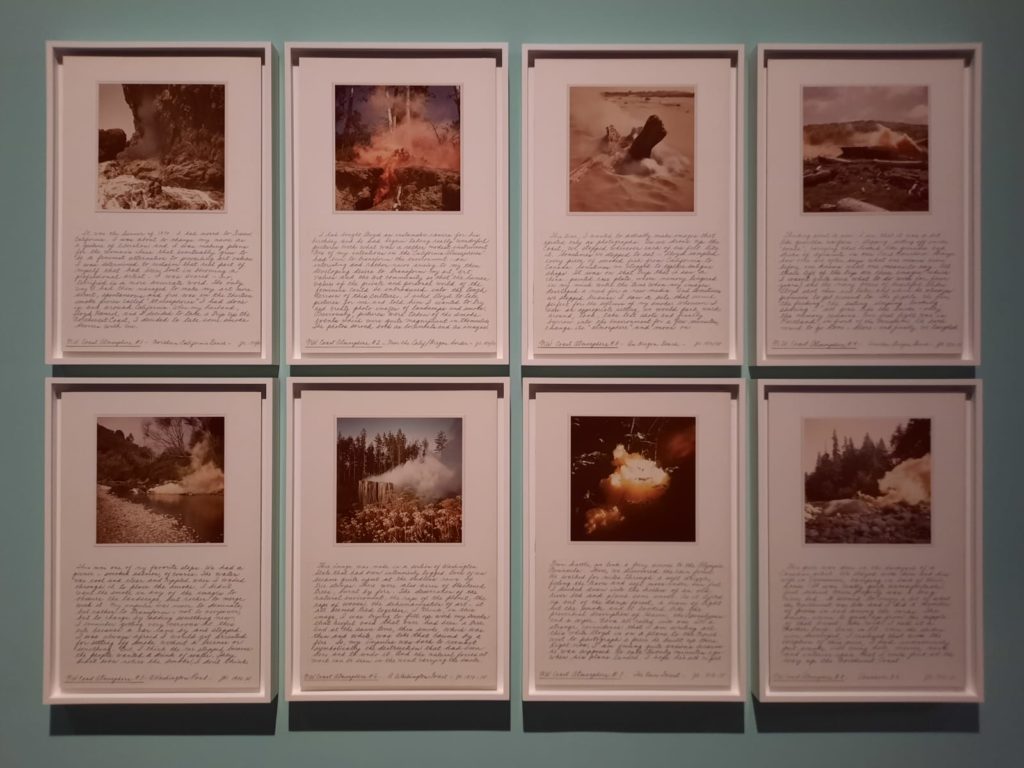

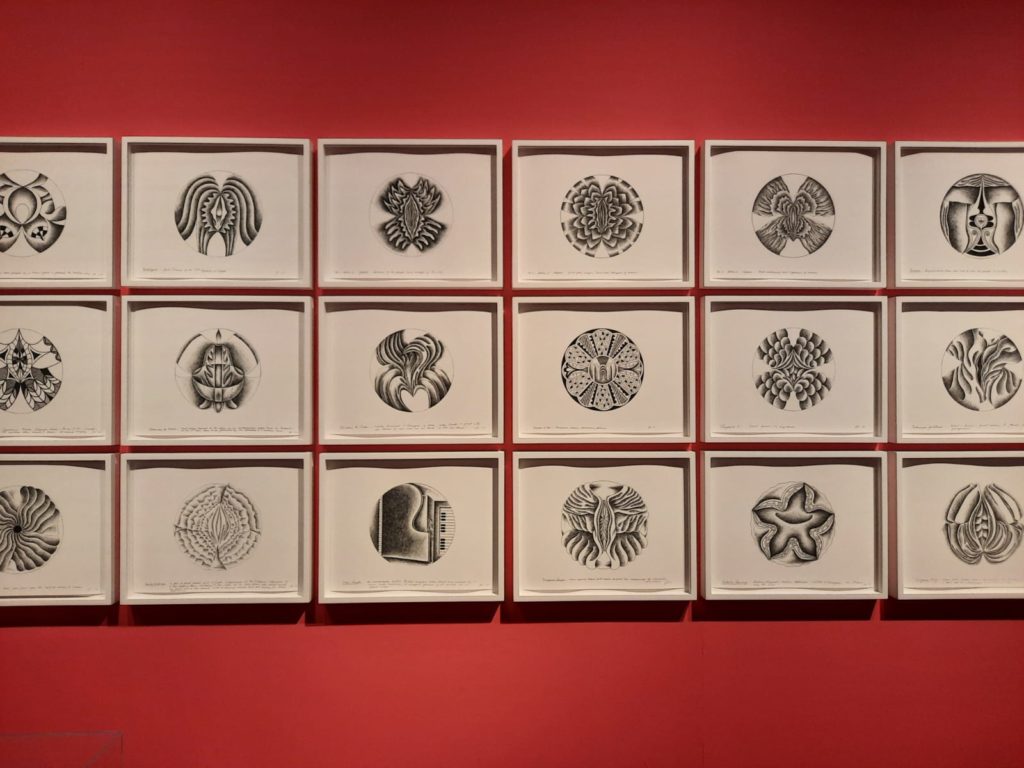

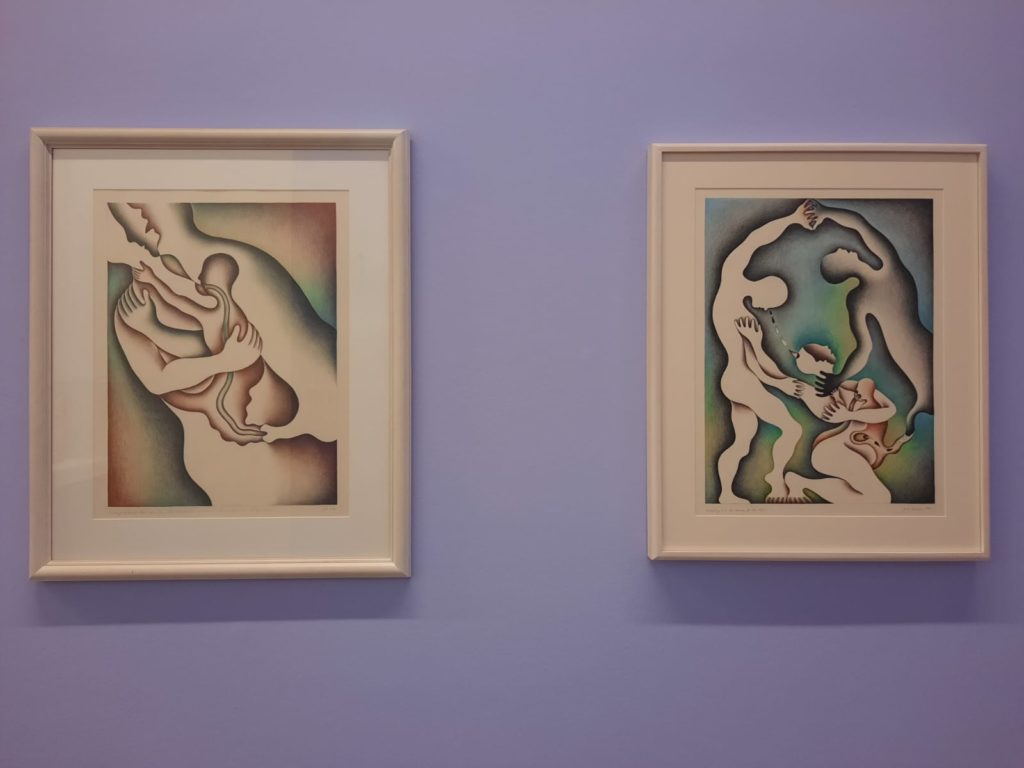

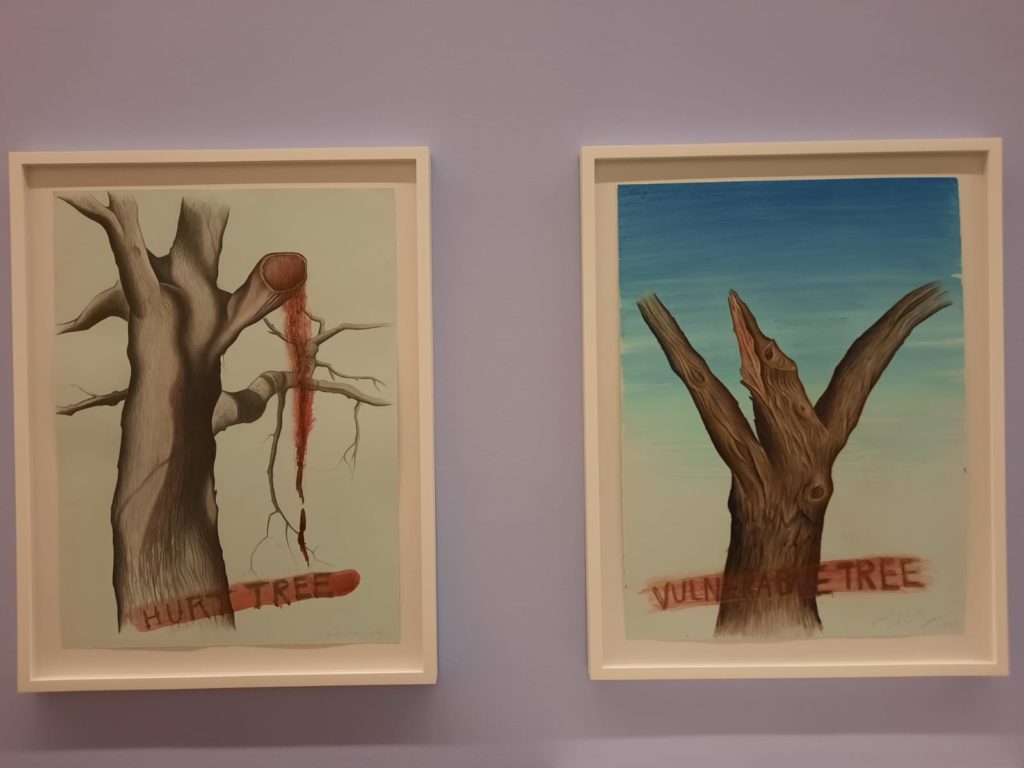

The exhibition thus focuses primarily on Chicago’s drawings and paintings. And the structure follows the chapters of the Revelations manuscript. I understand this from one perspective: it has made it worthwhile to finally publish a long-overlooked work from Chicago’s archive. And yet it seems a bit of a shame to have so much focus on ‘flat art’ when there are so many different media available in Chicago’s back catalogue. There are little spotlights on other types of art, for example her land/performance art, but my own interest in the topic left me wanting more.

As an introduction to Chicago, however, it is a pretty good exhibition. I got to know her signature style, saw works from different periods, and in (some) different media. Both Serpentine Galleries are relatively small, so the volumes are never overwhelming. And more than anything, I came to understand some of Chicago’s preoccupations: feminism and women’s bodies, stories and history; the environment; religion; power; and justice.

But What Did I Think of the Art?

This is actually a slightly complex question. I appreciated the art and Chicago’s contribution to centering women in an an artistic context. But the works themselves weren’t necessarily for me. It’s like Revelations: I’m glad of its preservation as an artwork and treatise. But I’m really not likely to read it.

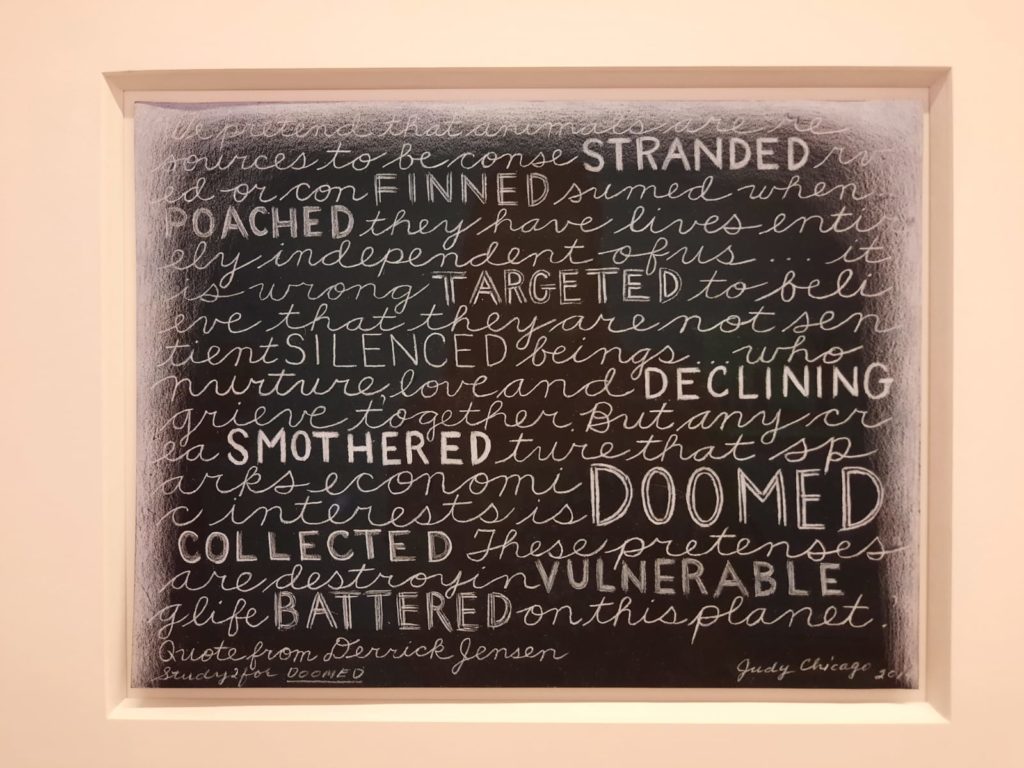

Is it that I have the privilege to have been born after, and benefitted from, first wave feminism? Perhaps. Early feminist artists had to be blunt in order to get their messages across and shift the needle. And this utter clarity is not only present in Chicago’s art when it comes to feminism. Some of the ecological artworks will also slap you across the face. But again – does the gravity of the situation warrant it? I don’t know.

I haven’t seen a Tate exhibition I really loved for quite a while now. But I do wonder if a slightly larger retrospective at Tate Modern might have been the thing. Get some bigger works in, explore more than the drawings. Or the Barbican, who did a great retrospective on fellow first wave feminist artist Carolee Schneeman. It’s possible that what I was responding to was the small scale of the exhibition coming off as a little timid. As special focus exhibitions go, this one is a valuable contribution. But at the same time I believe there are more exciting stories in Judy Chicago’s work waiting to be told to a UK audience.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Judy Chicago: Revelations on until 1 September 2024. Entry is free and the Serpentine South Gallery and Serpentine Pavilion are just a short stroll away.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.