A Summer Of Gods And Goddesses – The Gallery Of Everything, London

If you can’t get to Chandigarh, the Gallery of Everything’s current exhibition A Summer of Gods and Goddesses is the next best place to discover the work of Nek Chand Saini.

Nek Chand Saini and the Rock Garden of Chandigarh

When I visited the V&A’s exhibition on Tropical Modernism recently, one story stood out. Sure, the core subject matter about architecture, colonialism and independence was interesting. But what I really wanted to know more about was Nek Chand and his rock garden. It was a bit of an aside in the V&A, an example of resistance to and subversion of the imposition of Western architectural styles on Indian lives. Enter the Gallery of Everything, who shine a spotlight directly on Chand in A Summer of Gods and Goddesses.

So what is this business about a rock garden, anyway? And who is Chand? Well, Nek Chand Saini was born in 1924 in Shakargarh in the Upper Punjab. Displaced by the Partition of India in 1947 (his village is now in Pakistan), he found his way to Chandigarh in 1955. For many years he worked as a Roads Inspector for the Public Works Department. At the time, of course, Chandigarh was being utterly transformed by the Modernist project of Le Corbusier and others. Plenty of roads to inspect, I’m sure. Also plenty of discarded building materials, and perhaps a lax eye on what was happening in the city’s periphery.

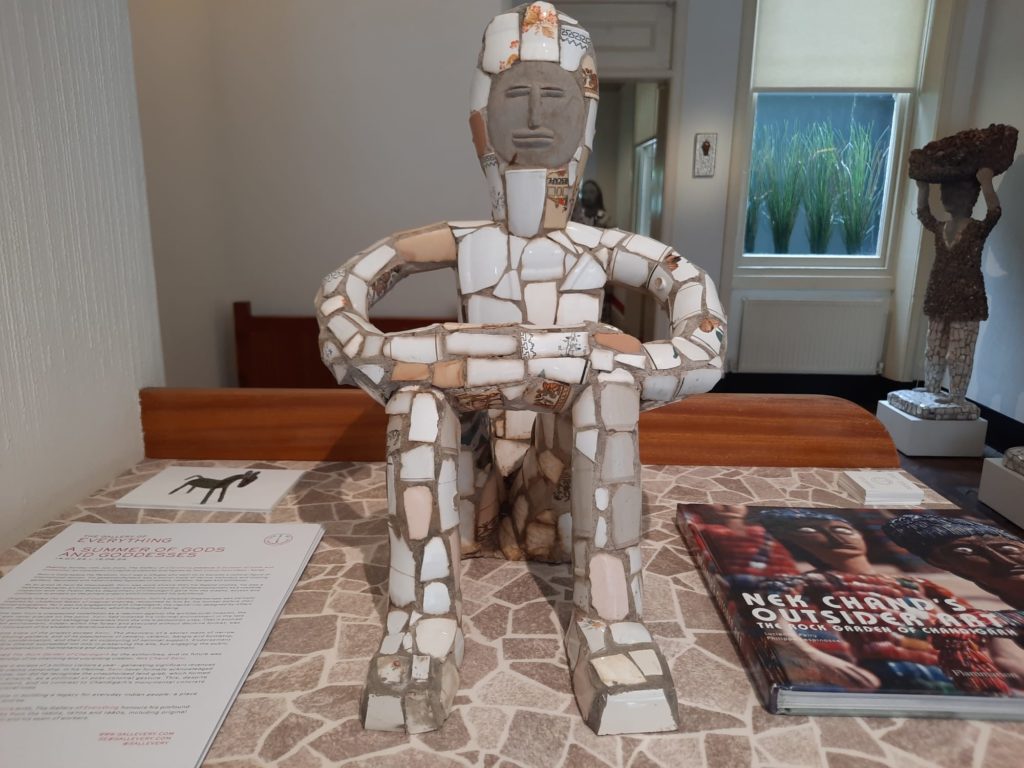

And so Chand began to take these discarded building materials and bits of rubbish, and to make something from them. Stones, concrete, bottle tops, broken bangles, iron foundry slag and ceramics, he had a use for it all. He never acknowledged the title of artist, but created nonetheless an immense artistic Gesamtkunstwerk, which as we have learned before means ‘total artwork’ – often using many art forms to create something all-encompassing. The authorities discovered his work about 18 years into it. By this time it covered acres of ground – a land grab Chand also declined to acknowledge. And from these secretive beginnings one of the most visited tourist sites in India was born. Even after Chand’s death in 2015, about 5,000 people per day still visit.

A Summer of Gods and Goddesses

A few sources say that Chand’s vision was to transform the marginal space he chose into “the Divine Kingdom of Sukrani”. I can’t find any mention of Sukrani online, other than in relation to the rock garden. Is it therefore his own divine vision? I guess so. It seems it was the intersection between his memories of stories from a childhood now out of reach beyond a new border, and the opportunities presented by the building sites of the planned city of Chandigarh.

It’s not surprising, perhaps, that Chand’s furtive creative acts have been seen as a reaction against the ‘architectural invasion’, as the Gallery of Everything put it. Le Corbusier had the actual nerve to include edicts banning cows and informal markets as part of his city plan (according to something I read in Tropical Modernism). In India. Patently ridiculous and putting people in the service of architecture instead of the other way around. Chand’s organic, ever-evolving work feels like the polar opposite to this approach.

The Gallery of Everything, in A Summer of Gods and Goddesses, have gathered a number of works representative of Chand’s style. Once his rock garden was discovered in 1978 it was at first at risk of destruction, until public support swayed the authority’s in Chand’s favour. They went as far as to give him a new job as Sub-Divisional Engineer, Rock Garden (note: not artist), with a team of 50 to support him. Chand therefore presumably had more leisure to produce works both for his garden and for other purposes. I’m not clear on how some have entered private hands as artworks given his reticence about positioning himself as an artist.

Meet Nek Chand Saini and his Gods and Goddesses

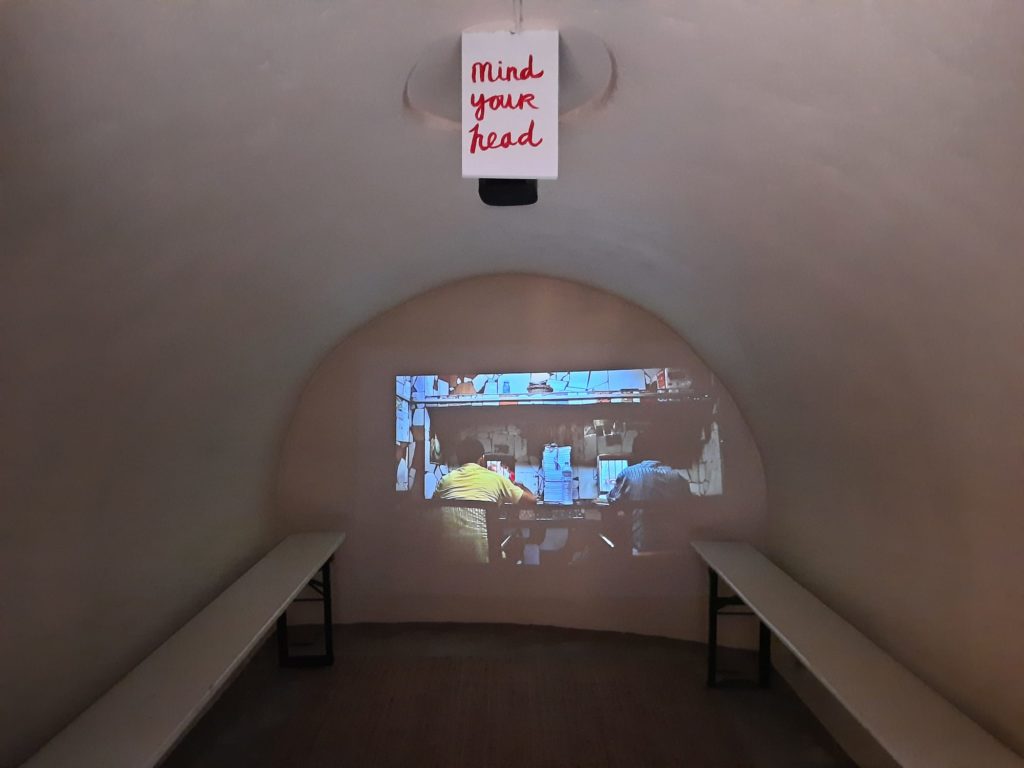

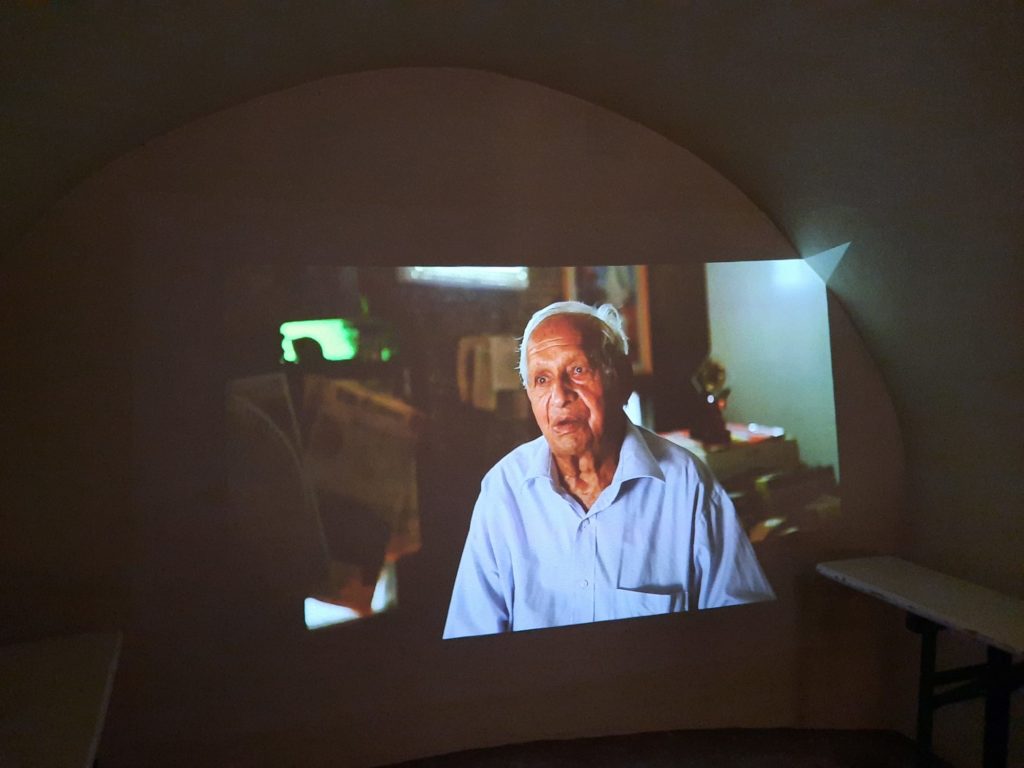

The works on display look perfectly at home in the Gallery of Everything. Its elegantly dilapidated interiors offset them so much more attractively than I can imagine a white cube gallery would. Their curving, organic forms seem to need a bit of life around them. Upstairs most of the works (I’m really trying to honour Chand’s terminology – he talked a lot about ‘working’ rather than creating artworks) are made of concrete, broken ceramics, pebbles. Their forms are nonetheless sinuous and inviting. In a back room a video plays where you can see an interview with Chand and footage of the rock garden. I think the same video plays downstairs – this one here.

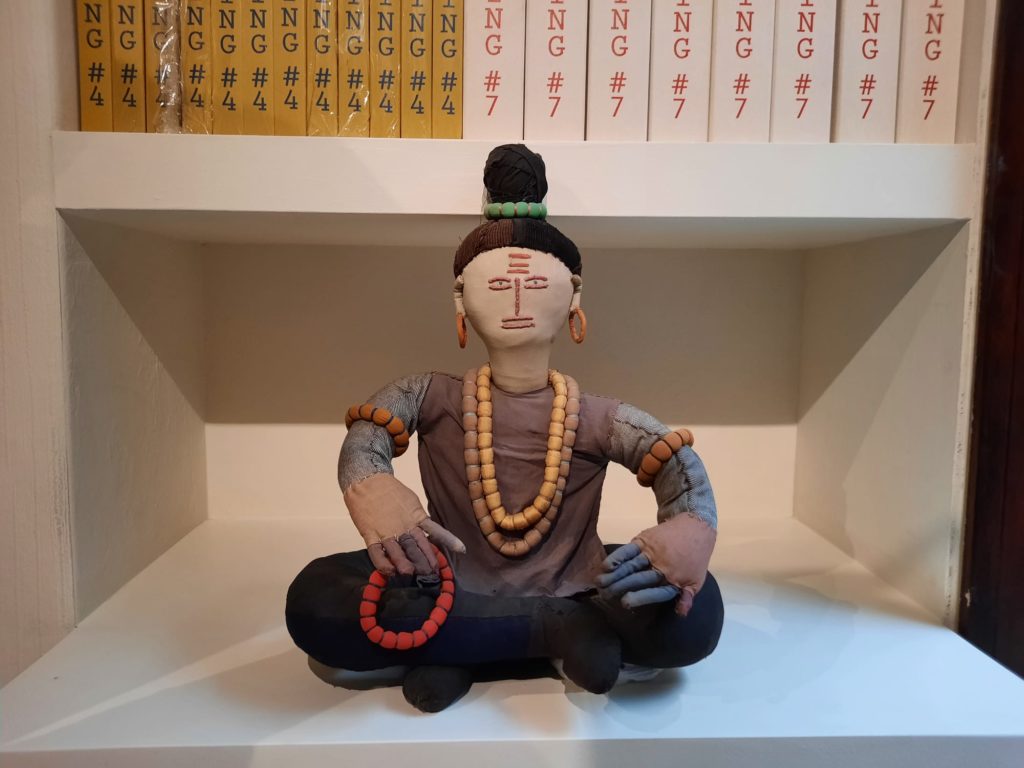

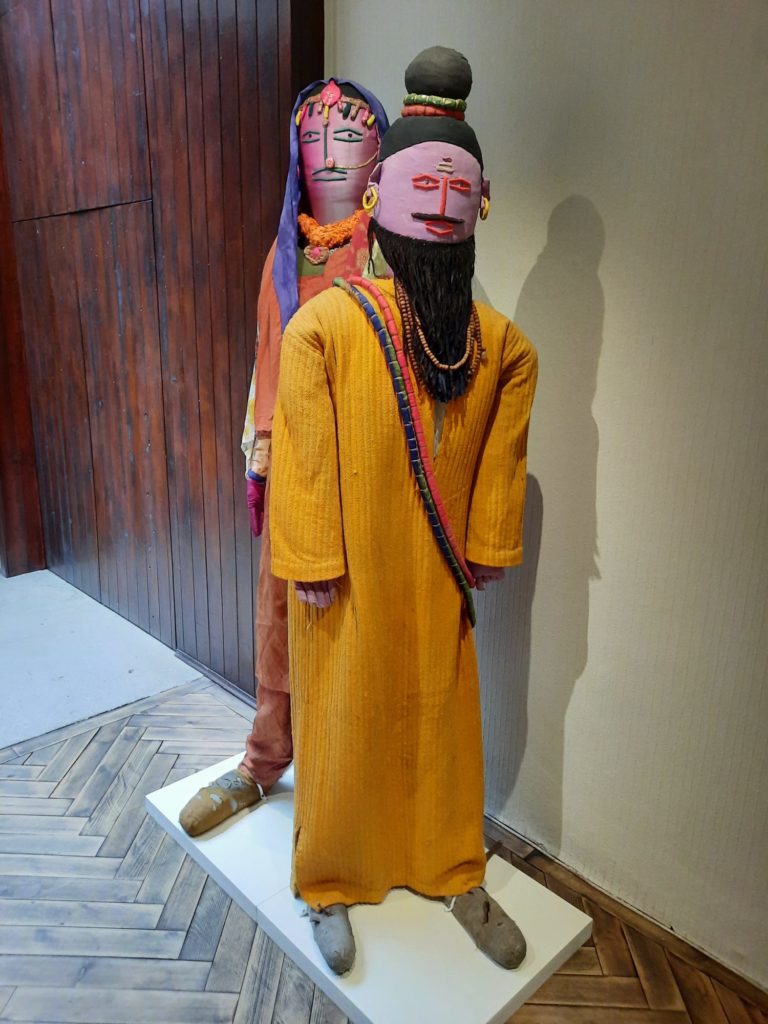

Downstairs, as well as a spot to sit down and watch the video through, are more works. Here we see a softer side, literally. A number of fabric dolls made by Chand in the 1980s and 90s add a pop of colour. More sculptural works accompany them. Not all take human form: there are also animals and a totemic figure. Not knowing when we are looking at a god or goddess versus a person is part of the point of this mystical kingdom, I suppose. Do take the time to watch the video through, if you visit. It whet my appetite even further to visit the rock garden in person one day. Particularly as the harsh conditions in Chandigarh will inevitably start to take their toll.

The timing of this exhibition and Tropical Modernism which introduced me to Nek Chand Saini is coincidental. The Gallery of Everything sometimes do tie-ins with major exhibitions (like this one or this one). But on this occasion A Summer of Gods and Goddesses coincides instead with the centenary of Chand’s birth. Appropriate, I would say, to be celebrated on his own terms rather than in opposition to the famous architecture of his adopted home.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

A Summer of Gods and Goddesses on until 15 September 2024

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.