Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King // Flora Yukhnovich and François Boucher: The Language of the Rococo – Wallace Collection, London

An exhibition on Sikh leader Ranjit Singh is an opportunity to learn more about a period of history little known in the UK, while Flora Yukhnovich’s paintings add a bright contemporary note to the Wallace Collection’s historic walls.

Indian Arms and Armour in the Wallace Collection

It’s been much longer than I realised since I’ve visited the Wallace Collection. It seems to be the exhibitions inspired by their South Asian holdings which attract me the most, and in Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King I saw a good example.

As an incredibly brief recap, the Wallace Collection “displays the art collections brought together by the first four marquesses of Hertford and Sir Richard Wallace, the likely illegitimate son of the 4th Marquess“. A lot of Old Masters, some furniture, applied art, and arms and armour. It opened as a museum in Hertford House, the former London home of the Marquesses of Hertford, in 1900. What is the connection, then, to the Indian Sub-Continent?

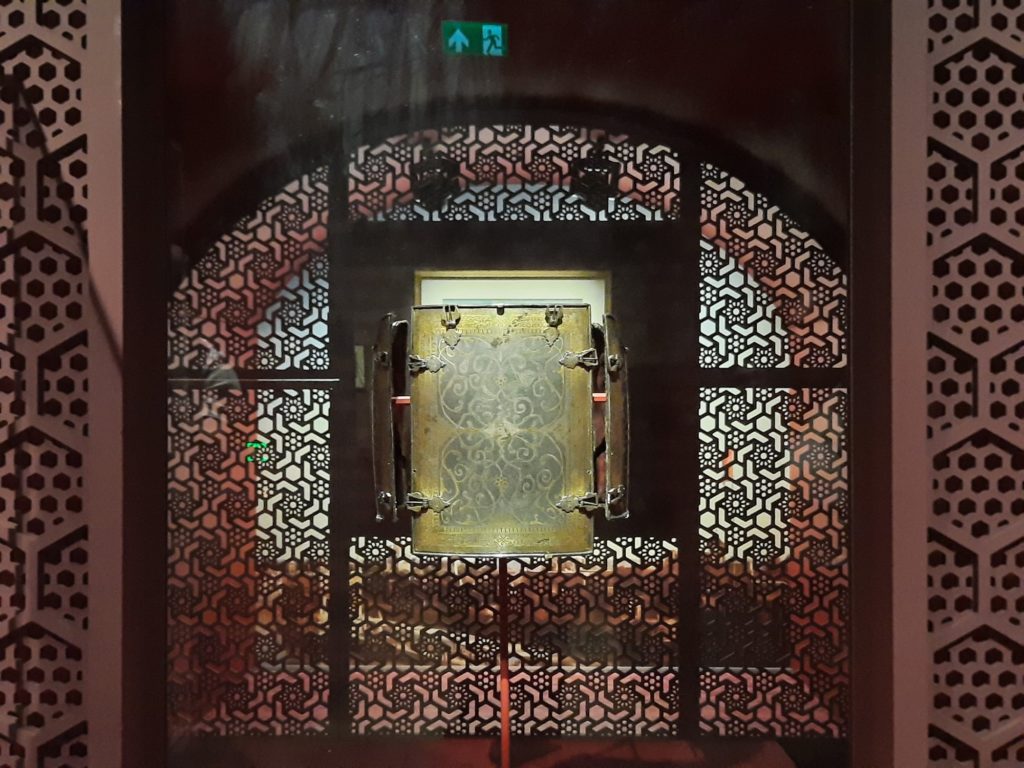

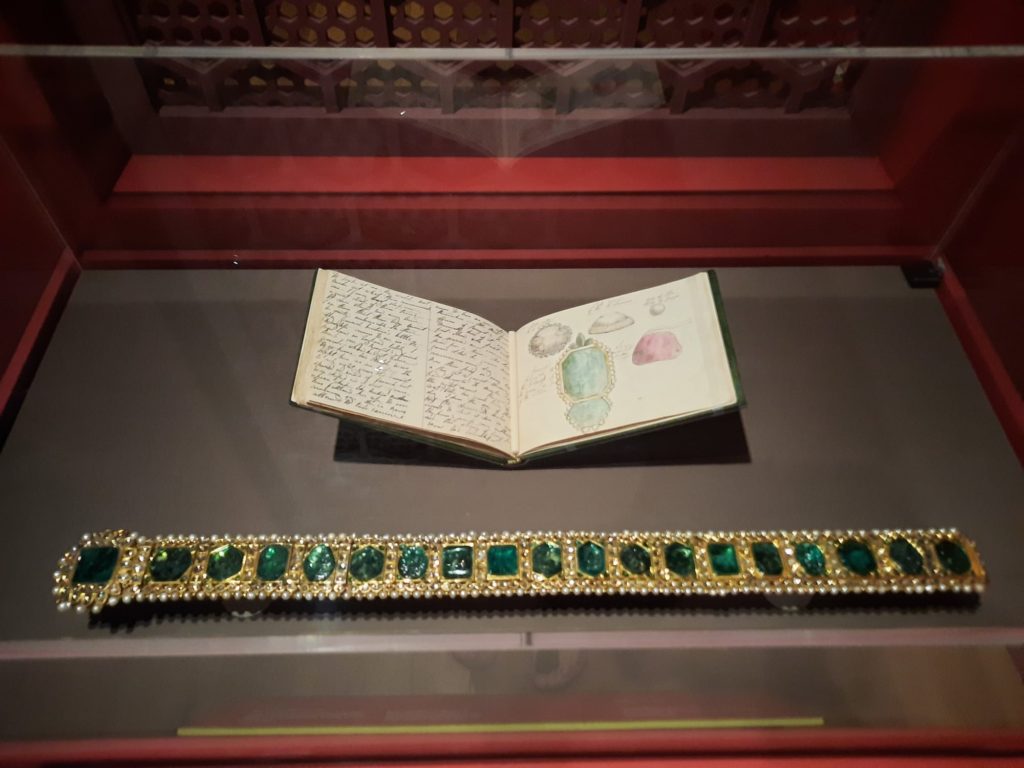

Well, as ever, we need to understand the historic context in which the collection was acquired. In the 18th and 19th centuries, when the collection was growing, England, and especially London, were at the heart of a powerful Empire. And the engine powering that empire, to a significant extent, was India. British influence in the region started in the form of the East India Company, but eventually led to direct imperial rule. Conflicts like the Anglo-Sikh Wars resulted not only in the annexation of land and seizure of power, but in the collection of arms and armour, jewels and other transportable assets as trophies, gifts or spoils of war. Once in the UK, these items either entered royal or private collections and stayed there, or changed hands on the open market. Many such items remain in British collections today and reflect this colonial history.

And so we can see the inclusion of Indian arms and armour in the Wallace Collection (and similar collections) in this light. For the collector: works of often exquisite craftsmanship telling important stories. For the source community: often carrying additional meanings beyond what the average visitor sees at face value.

Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King

That is the first bit of important background covered. Now for the next bit: who was Ranjit Singh and what is the significance of this exhibition?

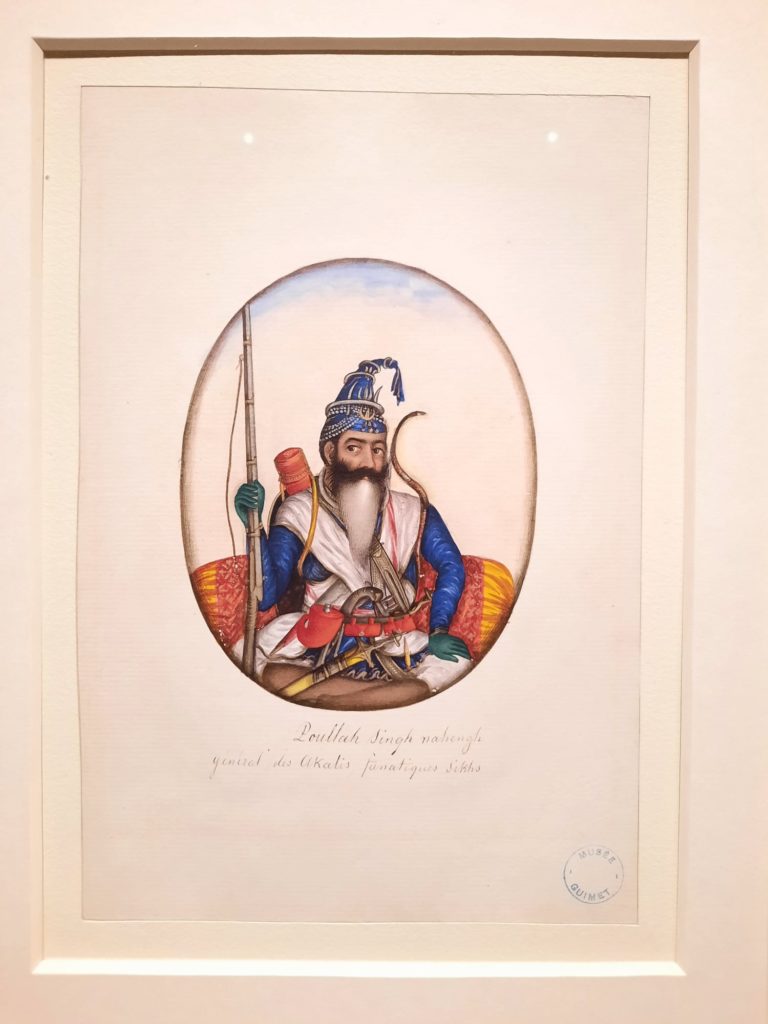

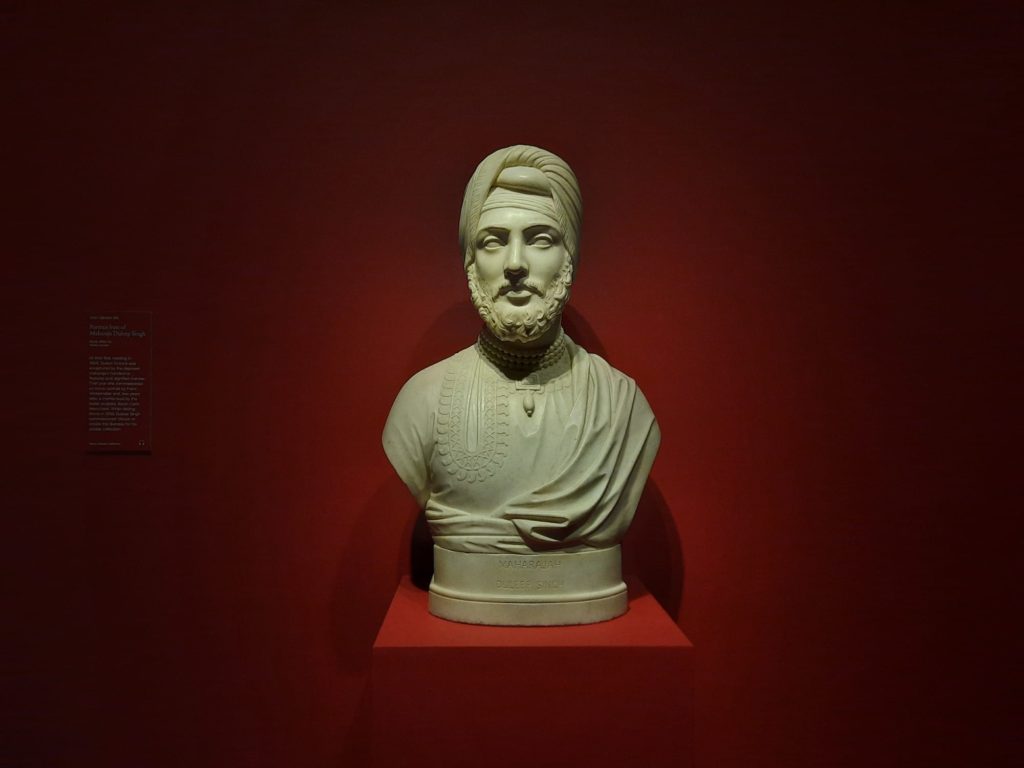

Ranjit Singh was born in 1780. He survived smallpox in infancy, but was left with a damaged eye. As a teenager, he showed military leadership in campaigns to oust the Afghans from the Punjab. This led to him being proclaimed the Maharaja of Punjab in 1801 (his nickname was Sher-e-Punjab or the Lion of Punjab), uniting several warring misls or confederacies. Through to his death in 1839, Singh established an increasingly powerful state, known for its religious tolerance and effective administration. He resisted external threats, and brought peace and prosperity to his subjects.

As is often the case with such a strong leader, a succession crisis emerged after Singh’s death. Singh had many children by his wives, including a number of sons. His eldest son Kharak Singh was the second Maharaja, but succumbed to one of several assassinations and murders within the court. The British spotted an opportunity and stoked the flames. A second Anglo-Sikh War from 1848-49 spelled the end of the Sikh Empire. The then Maharaja, Ranjit Singh’s youngest son Duleep Singh, lived in exile in England from then on. The ‘spoils of war’ included some of the items on display in this exhibition, as well as the Koh-i-Noor diamond still part of England’s Crown Jewels today.

Despite this illustrious and important history, Ranjit Singh is not a well-known figure in the UK today. Or not universally well-known. The Sikh population of over half a million makes it the UK’s fourth-largest religion. Exhibitions such as this are therefore speaking to two very different audiences: one discovering Ranjit Singh for the first time, and one here to deepen their knowledge and connection to a figure of cultural and historic relevance.

Telling Ranjit Singh’s Story

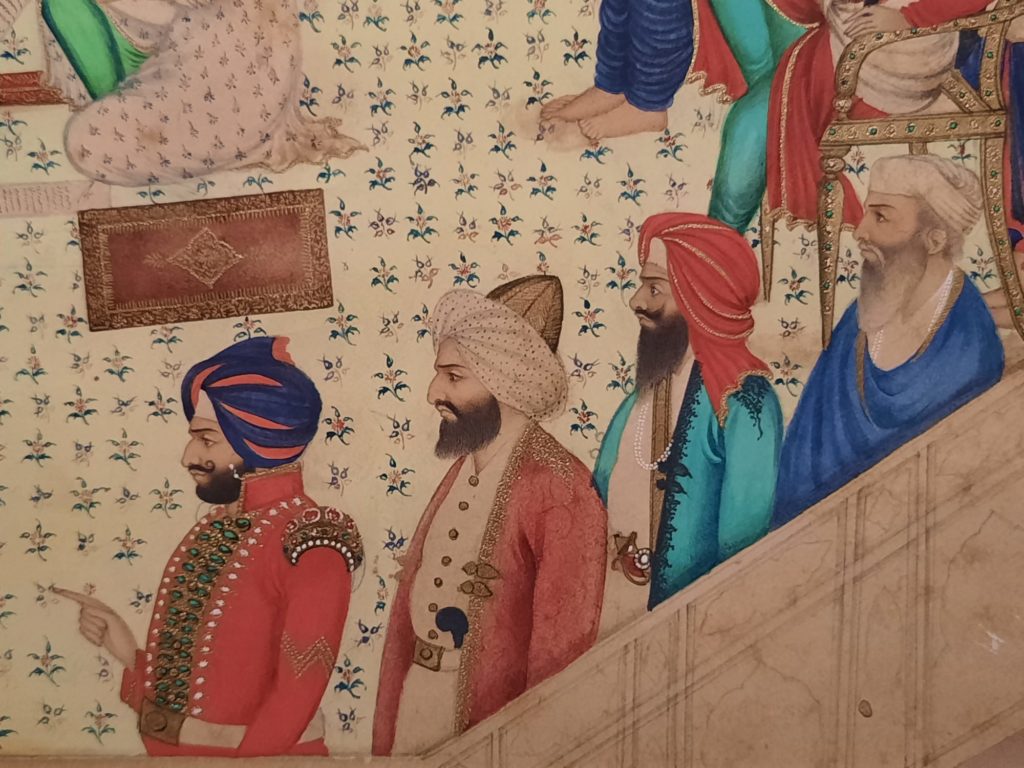

So, then. How do the Wallace Collection do at bringing this story to life, for two distinct audiences? On the whole, I would say pretty well. The Wallace Collection’s downstairs exhibition space is a nice size. It also lends itself to setting out a good introduction before getting into detail. Here we have an introductory section with background on Singh, the Punjab and the Sikh Empire, before exploring weaponry, Singh’s court at Lahore, foreign invitees to the court, and his legacy.

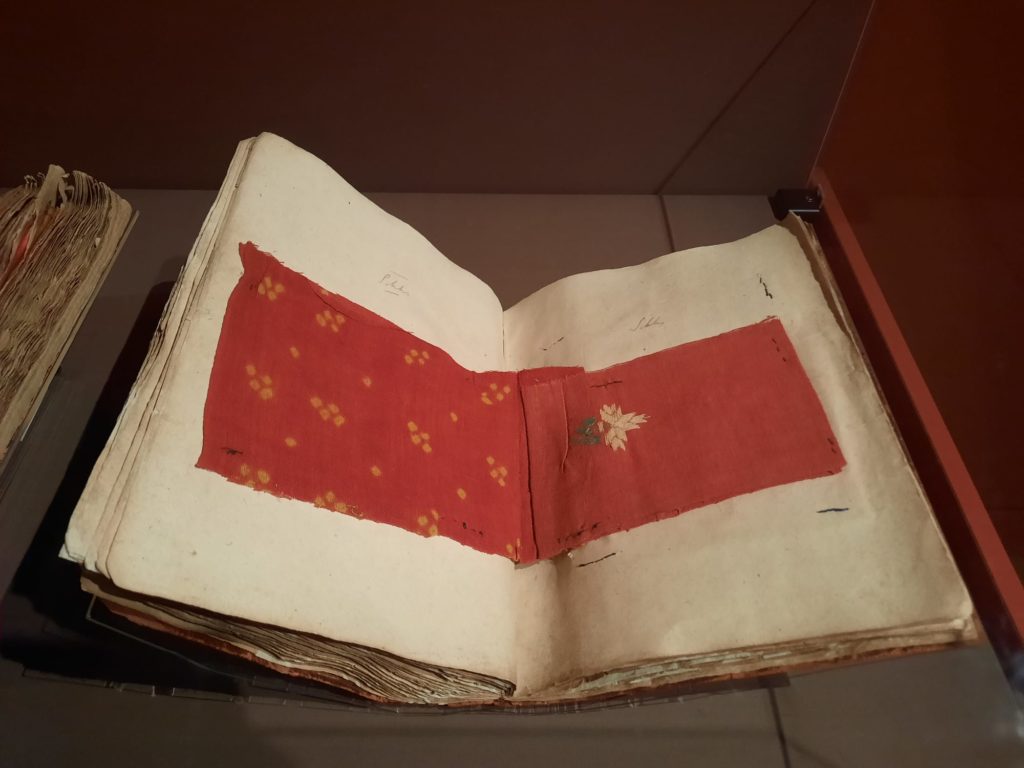

In terms of the Wallace Collection’s own holdings relating to Ranjit Singh, I believe there is only a single object: a sword which reputedly belonged to him. The rest are loans, the overwhelming majority of which come from the Toor Collection. Davinder Toor has amassed a great collection of Sikh art and artefacts, many of museum quality. I am typically a little suspicious of exhibitions which give pride of place to private collections: they can be a cynical means of increasing legitimacy and value. But, in this case, Toor’s collection rather fills a gap where other institutions are lacking representation of the Sikh community. And it’s a broad collection, contributing here a range of paintings, textiles, weapons, photographs, letters, and more. It’s clear the exhibition could not have happened in this format without this collection.

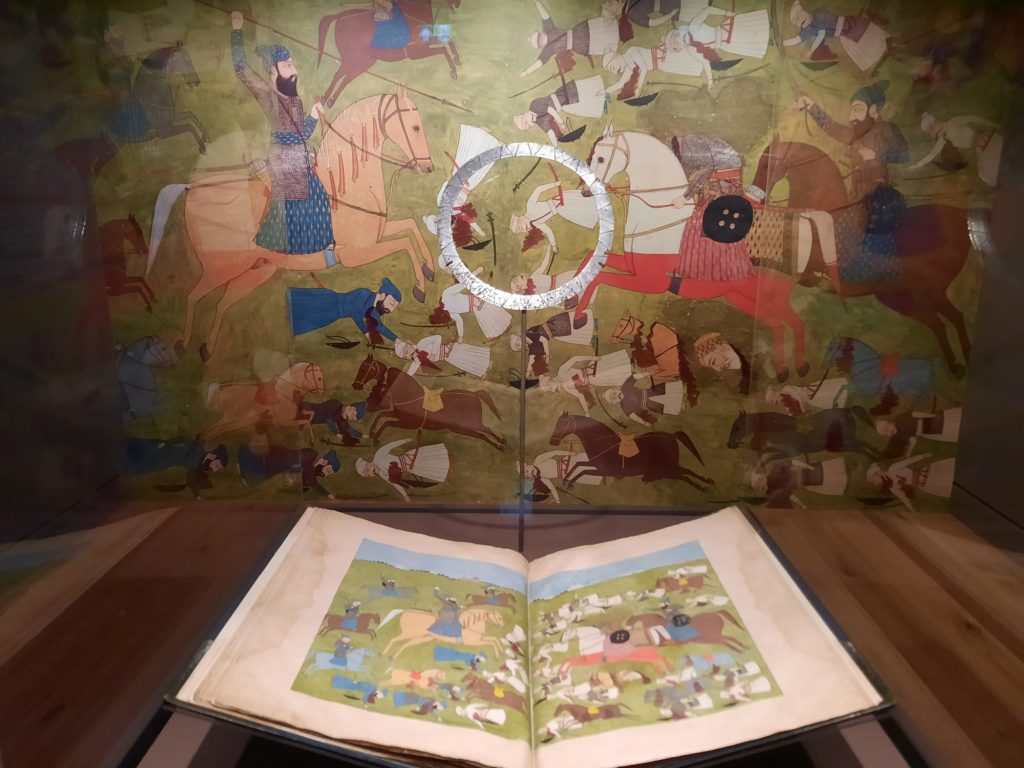

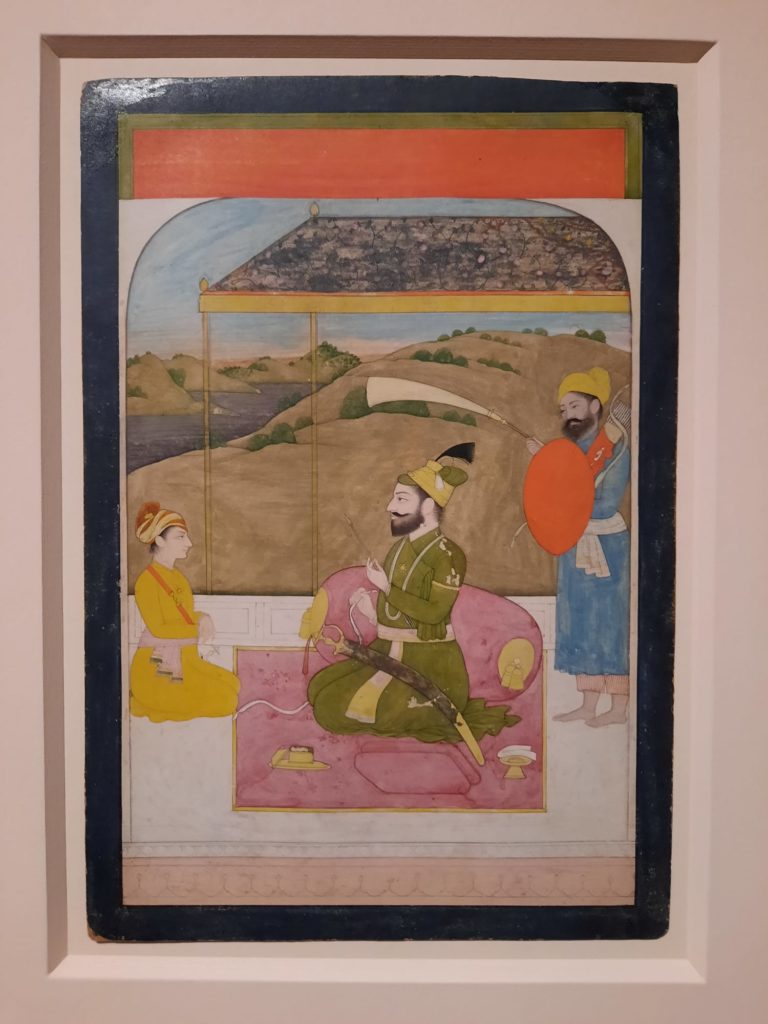

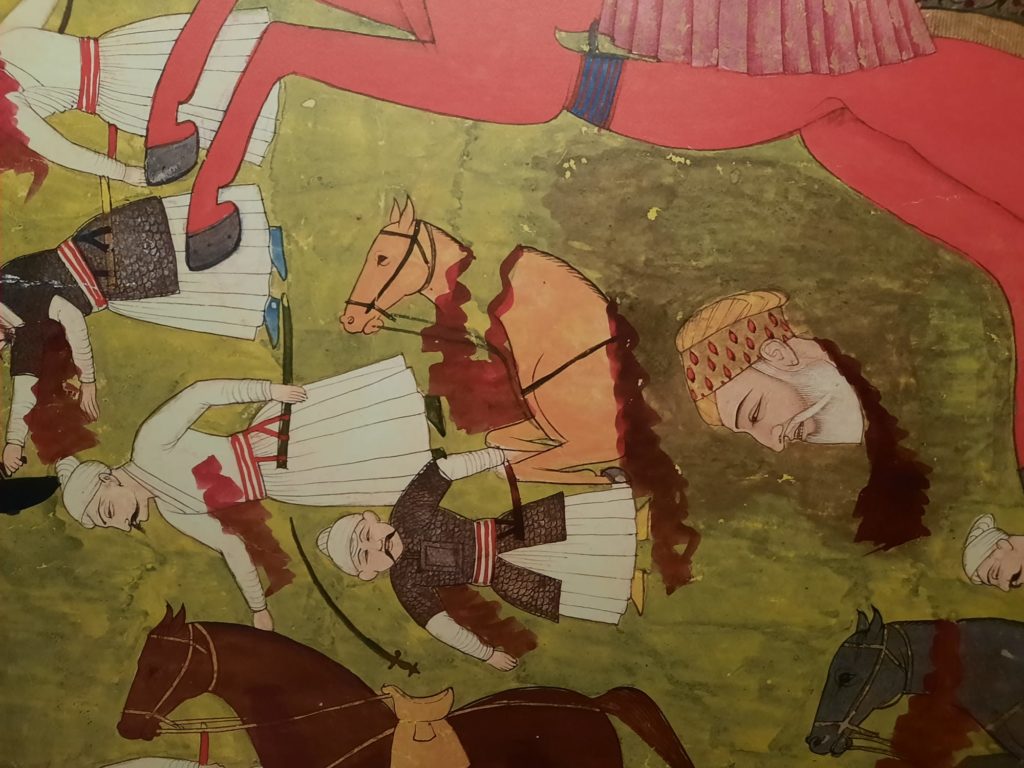

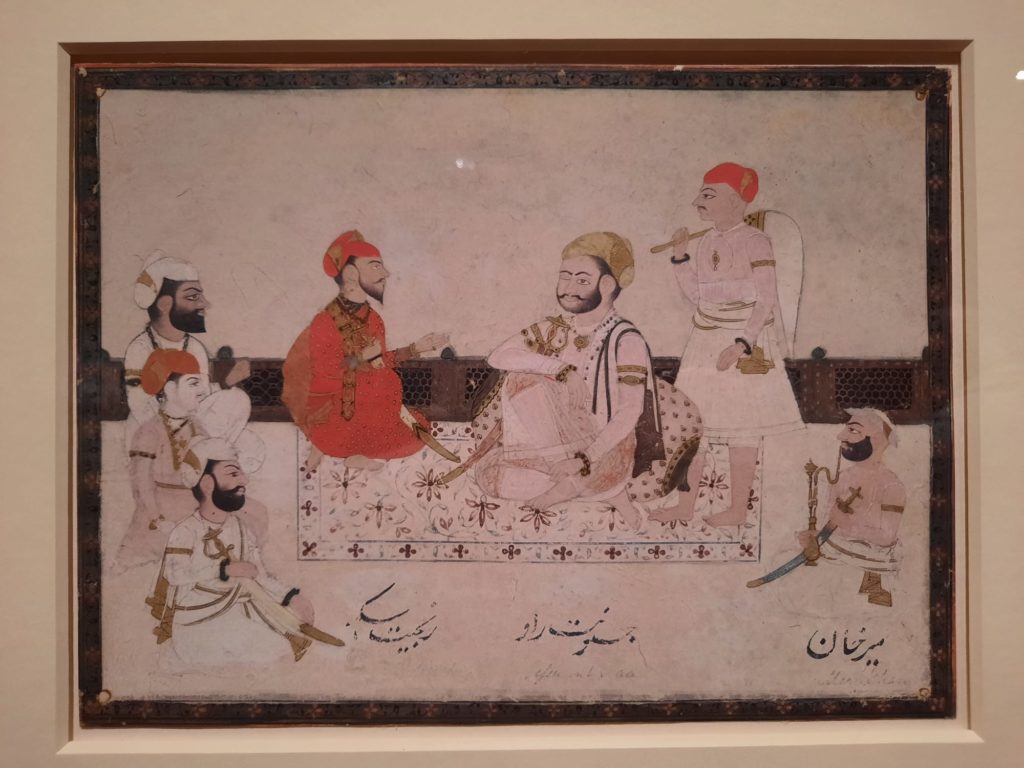

Back to the visitor experience. The exhibition is quite information-dense, as you might imagine. With such a lot of ground to cover it can only scratch the surface. But it does at least touch on some of the trickier subjects like how these objects ended up leaving the Punjab in the first place. And creates a fairly well-rounded view of a progressive court. Singh’s invitation to foreign military veterans to help create a modern army is particularly interesting. In terms of the objects, some of my favourites were the detail-rich paintings, painted with all the miniaturist’s skill first honed in India’s Mughal court.

Final Thoughts on Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King

So if I summarise my thoughts on Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King, it would be more or less the following. Although the connection between the Wallace Collection and Ranjit Singh is slight, there is nonetheless a connection. And taking a wider view, the Wallace Collection’s assemblage of arms and armour is very much in the vein of collections which bought up examples of workmanship or storied objects from colonial territories.

This is just one of many stories which Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King attempts to cover in a short space of time. On the one hand, its a shame not to be able to get more in depth on topics of interest. I suspect any one of the sections of the exhibition could be an exhibition in its own right. But on the other hand this exhibition begins to redress a gap in museum programming around Sikh history and Sikh stories. The large proportion of Sikh families there when I visited show that there is a market and an appetite from within the community, and I suspect more widely as well.

For now, the preservation of these histories is, at least in part, down to individuals like Davinder Toor, who also co-curated this exhibition. I hope that in time these objects will have their long-term preservation assured one way or another, so that stories such as this can continue to be told.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King on until 20 October 2024

Flora Yukhnovich and François Boucher: The Language of the Rococo

Just before we leave the Wallace Collection, I have a bonus exhibition for you. This one is free, imbedded within the permanent collection. Flora Yukhnovich and François Boucher: The Language of the Rococo blurs the lines between contemporary and historical art.

The premise of the exhibition is an interesting one. The Wallace Collection have commissioned two works from Yukhnovich. They take the place of two works by François Boucher which normally hang at the top of the grand staircase. The new paintings, although a very different style, somehow look at home in their gilt frames. The Bouchers, in turn, have been moved down to a room off the shop, known as the Housekeeper’s Room. Here they stand proudly out of their frames, a mode of display we are much more familiar with in contemporary art. A playful inversion.

What is interesting is how well Yukhnovich’s semi-abstract style captures the spirit (or the language, per the title), of the Rococo. Rococo is of course the style in which Boucher painted: lots of pastoral, fantastical scenes of love and pleasure. Yukhnovich’s works have the same lightness and playfulness, and a take on the same tones. It’s a nice way to subvert our expectations of an otherwise very historic and traditional collection, although you could miss it if you’re not paying attention or don’t follow the signs to the Bouchers.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Flora Yukhnovich and François Boucher: The Language of the Rococo on until 3 November 2024

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.