Ferens Art Gallery, Hull

My recent trip to Hull allowed me to visit one of the UK’s best regional art collections at the Ferens Art Gallery. Join me to learn more about this institution, its origins, and what you can see and do there today.

A Little Background First: Thomas Ferens and the Ferens Art Gallery

On my recent short visit to Hull, one institution was high on my to do list: the Ferens Art Gallery. I’ve written before about the UK’s regional art galleries, and how they often have links to philanthropy, industry and commerce. Many started life as personal art collections, gifted to local authorities as a way to ensure a legacy. It’s one reason the UK has such strong regional holdings of Victorian and Pre-Raphaelite art.

The Ferens Art Gallery has some similarities with this trend, but also key differences. And it seems to me that the differences have a lot to do with personality, so we would be best to start there and learn more about Thomas Robinson Ferens. Born in 1847, he was the son of a flour miller. This afforded him an education in a private school before, aged 13, he found employment as a clerk. He continued to study in his spare time, teaching himself shorthand amongst other things. He was also a keen cricket player and, as devout Wesleyan Methodist, taught Sunday School. In 1868 he took up a post as a confidential shorthand clerk at Reckitt and Sons, and moved to Hull.

Ferens stayed at Reckitt and Sons until his death in 1930, eventually rising to the post of chairman. As an aside, Reckitt and Sons still survives as part of Reckitt Benckiser, which owns Boots, Dettol, Strepsils, Veet and other well-known brands. Ferens was also an MP from 1906-1918, and from the beginning of his success in business was a committed philanthropist. At the beginning this meant setting aside 10% of his salary for charitable donations. But later in life Ferens was able to make substantial donations to endow almshouses, today’s University of Hull, and the Ferens Art Gallery.

The Ferens Art Gallery, 1927 to Today

Ferens supported an art gallery for the city of Hull in two to three phases. Firstly, in 1905, he donated money to the Hull Corporation so they could start an art collection to complement their museum. This first iteration of an art gallery opened above the existing Municipal Museum. In 1917 Ferens went even further. He purchased land on the site of a former church, and donated it (along with some company shares) to the council for the purpose of building an art gallery. This art gallery, the same building we will visit today, opened in 1927.

And what about the collection? Well, this is where I see an interesting divergence from some other local art galleries of this era. The Ferens Art Gallery seems to have been more about getting Hull an art gallery than about a legacy for Ferens and his own art collection. The lines are a little blurred given that it does bear his name and he collected a lot of the Victorian works in particular, but this very much feels like a municipal collection rather than a personal, time capsule collection. Ferens’ sober, Methodist tastes are credited within the gallery as the reason there’s very little Pre-Raphaelite art, however, so his influence is there nonetheless.

Thanks to an endowment from none other than our friend Thomas Ferens, the Ferens Art Gallery have continued to acquire more works and enhance the collection over time. Other works have entered the collection thanks to schemes involving the V&A and the Art Fund, or as gifts and legacies. So like many regional galleries, what we see today is part collecting strategy, part haphazard. Temporary exhibitions can be a way to focus on areas not strongly represented in the Ferens Art Gallery’s holdings. Contemporary art, for instance: you will spot giant inflatable sculptures in one or two images here from a now-past exhibition of work by Jason Wilsher-Mills.

The Visitor Experience

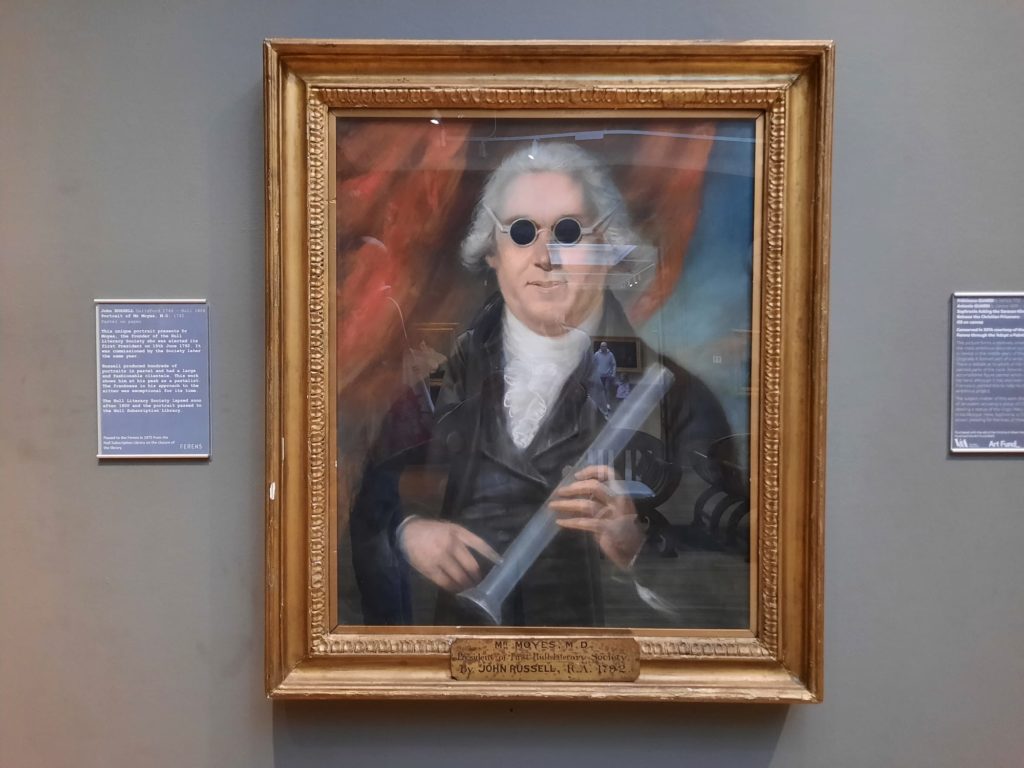

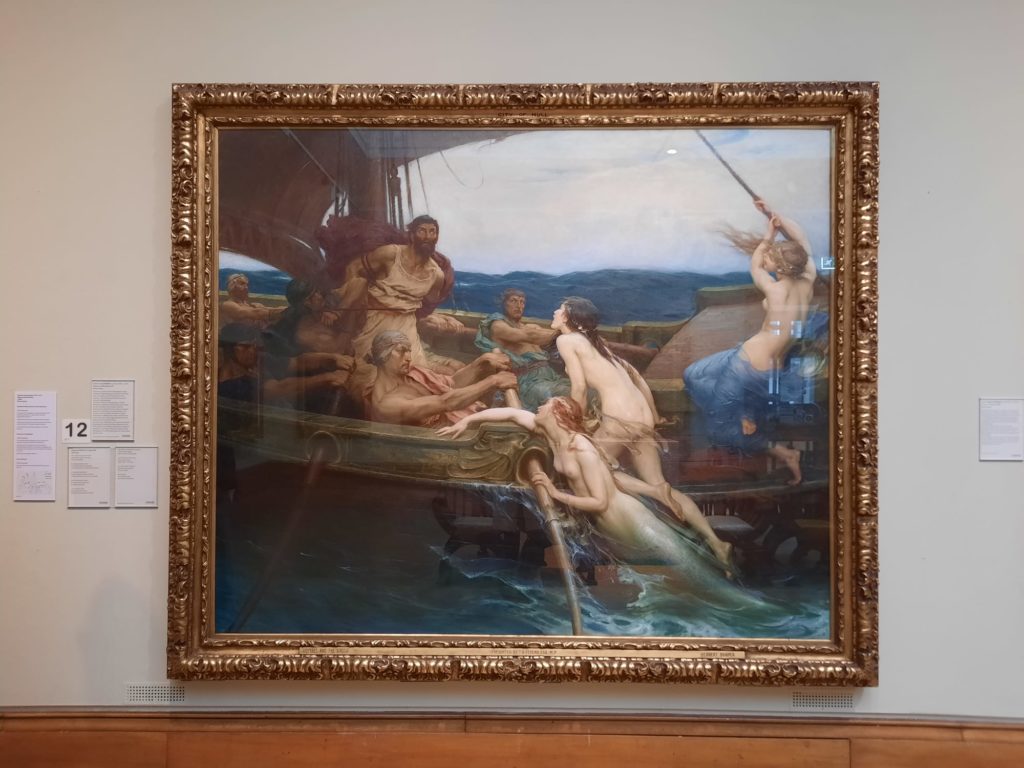

Visitors will find the Ferens Art Gallery easy to navigate. It’s also free to visit, which is also a bonus. We had a warm welcome from visitor hosts when we arrived, and were pointed in the right direction to start a chronological visit. What is on view is a relatively small selection in the grand scheme of things, but gives a good overview of Western art history of the last few centuries. We start with Renaissance and Baroque art. Next up is the Dutch ‘Golden Age’ (more on terminology in a moment). Then there’s 18th century Europe, before a healthy smattering of that Victorian art we were talking about. We then move on to the 20th century, with space for some temporary exhibitions. After all that I was worried we would have the same volume again upstairs, but discovered there was merely a small mezzanine gallery to finish.

As an outsider to the city, I was interested to see how the Ferens Art Gallery would address topics like historic sources of wealth, the city’s ties to Empire and the trade in enslaved people, and contemporary perspectives on historic art. And my verdict was that there were some interesting inroads into surfacing difficult histories, without taking a fully radical approach.

For instance, right from the outset audience voices are welcomed into the gallery. Texts next to various paintings explain why participating visitors enjoy a certain work, or the value it holds for them. A great way to encourage a plurality of perspectives. LGBT+ connections and stories are also visible through specific branding on some texts. And yet in the Dutch gallery I felt a tension between the discussion of representations of Blackness in Dutch painting, and the continued use of the term ‘Golden Age’ which is starting to fall out of favour. I guess the point is that inclusivity can be a journey rather than a revolution.

Final Thoughts

The Ferens Art Gallery is, as promised, an excellent example of a regional art collection in the UK. Within just a few rooms you can see works by Frans Hals, Canaletto, Francesco Guardi and a rare Pietro Lorenzetti. The explanations are accessible, engaging, and cover a multitude of different points of view. As far as free art historical resources go, the people of Hull are pretty lucky.

I also found it interesting as an example of a sort of religious philanthropy that is much less common in the UK today. Despite massive wealth inequality, to rise from clerk to chairman seems to have been a possibility for many enterprising Victorian men. Some of these men wanted the name they had built to live on after their deaths. Others were part of religious movements championing temperance, humility and charity. Ferens was in the latter camp, but either way his gifts to the city of Hull are not unique. Victorian England was almost like the Roman Empire in terms of privately-funded public projects: a reputational incentive to contribute. Granted, we’re talking 1905-1927 so post-Victorian. But Victorian morals had a long-lasting impact so I’m counting Ferens as a Victorian man nonetheless. A bit like Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, who continued to be a proud Victorian well into her old age.

But enough of these asides. For visitors to Hull, the Ferens Art Gallery is worth adding to your itinerary. Its central location and free entry are definite draws. Plus it is a nice size: not so small as to not be worth it, but not so large as to be tiring. With almost a century under its belt now, I hope the Ferens Art Gallery will continue to the cultural life of the city for many years to come.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

Wow – it looks so much more impressive than one might expect in a regional location – well done Ferens and those who followed! Some really outstanding artworks.

Yes definitely a highlight in Hull, with good contemporary exhibitions alongside the historic collection!

“I was interested to see how the Ferens Art Gallery would address topics like historic sources of wealth, the city’s ties to Empire and the trade in enslaved people”

Hull has an entire museum about slavery. The city’s historic sources of wealth – trade across the North Sea to the low countries, Scandinavia and the Baltic, as well as the much better known whaling and fishing – are covered by the maritime museum, though it is temporarily closed.