A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang – British Library, London

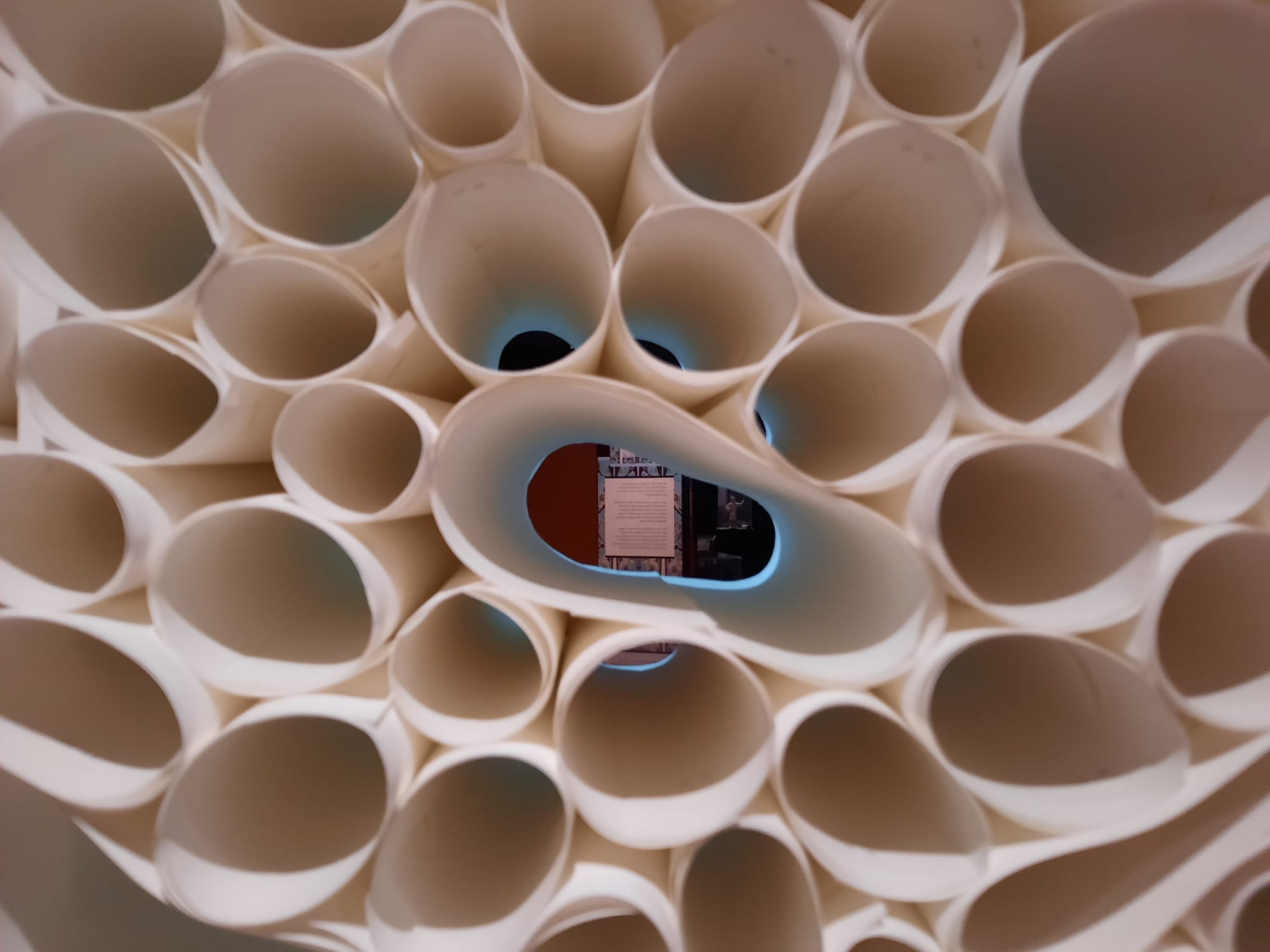

One of two exhibitions in London devoted to the Silk Road, the British Library’s offering, A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang focuses in on the treasures of one remarkable cave, and the insights they offer into ancient people’s lives.

A Silk Road Oasis

Sometimes great minds really do think alike. How else to explain the coincidence of two exhibitions at once on the Silk Road, one at the British Museum and one at the British Library? To my knowledge, there isn’t an anniversary or any other particular reason to explain scheduling them now.

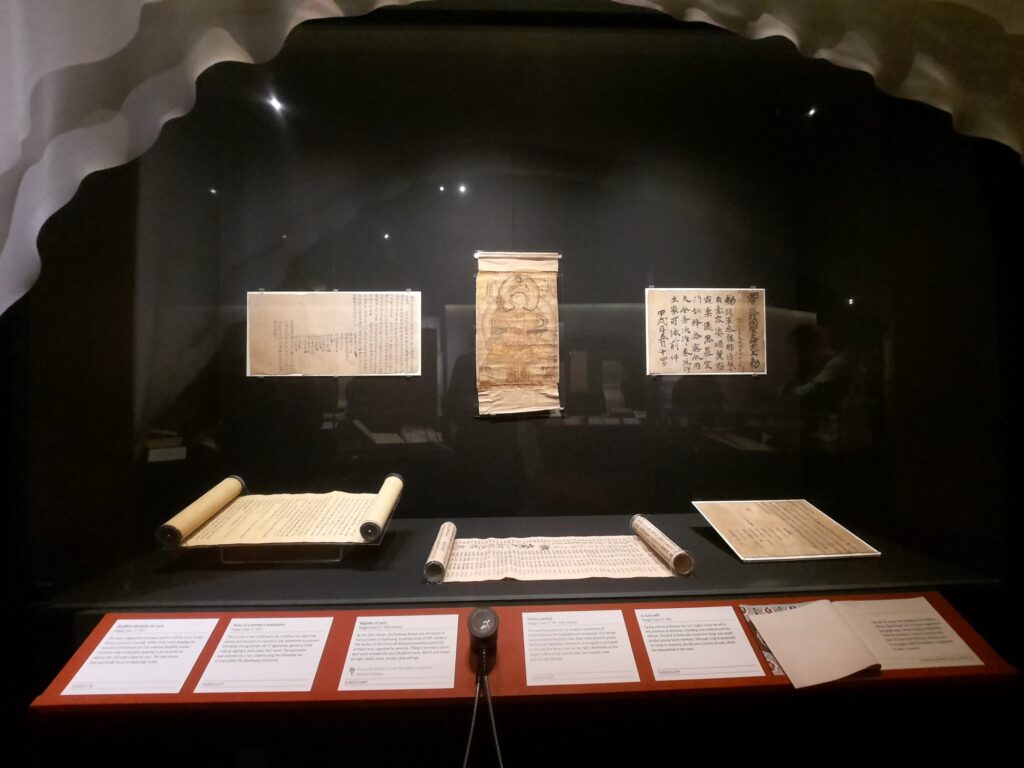

Thankfully the great minds did not take exactly the same approach to these thematically similar exhibitions. I haven’t (yet?) visited the British Museum exhibition, but I understand it challenges the idea of a Silk Road as a construct, conveying instead the idea of a vast trade network across civilisations and continents. The British Library exhibition is almost the exact opposite. That is to say, it focuses in on just one spot on the so-called Silk Road, and explores the cosmopolitan world created here by trade.

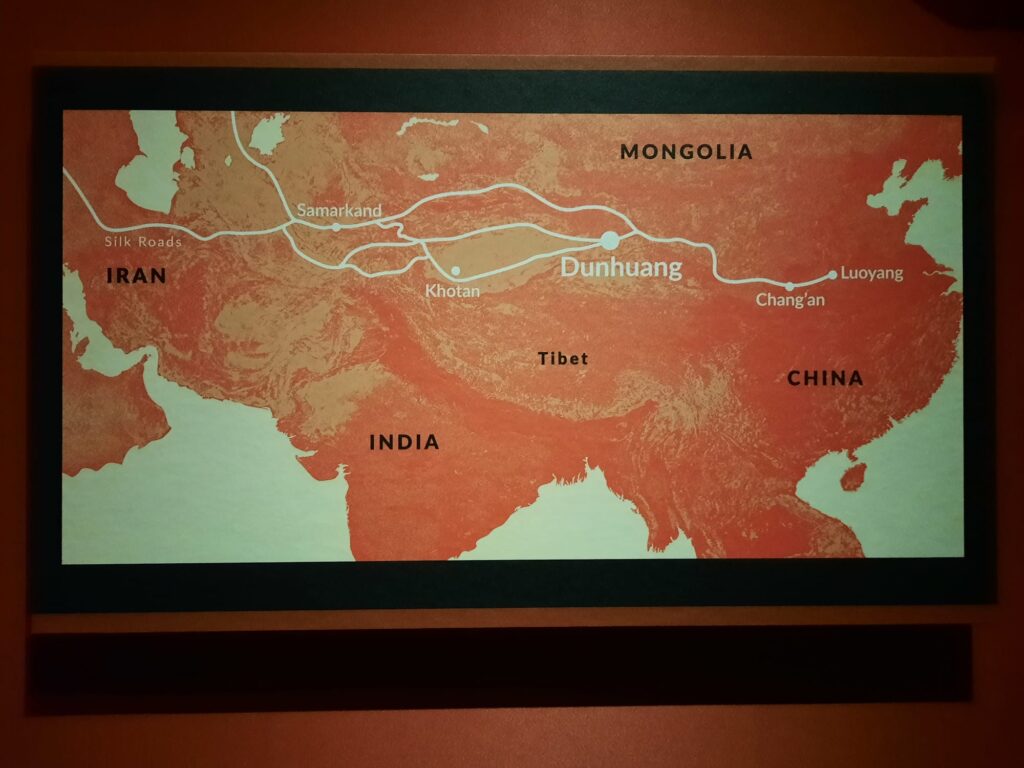

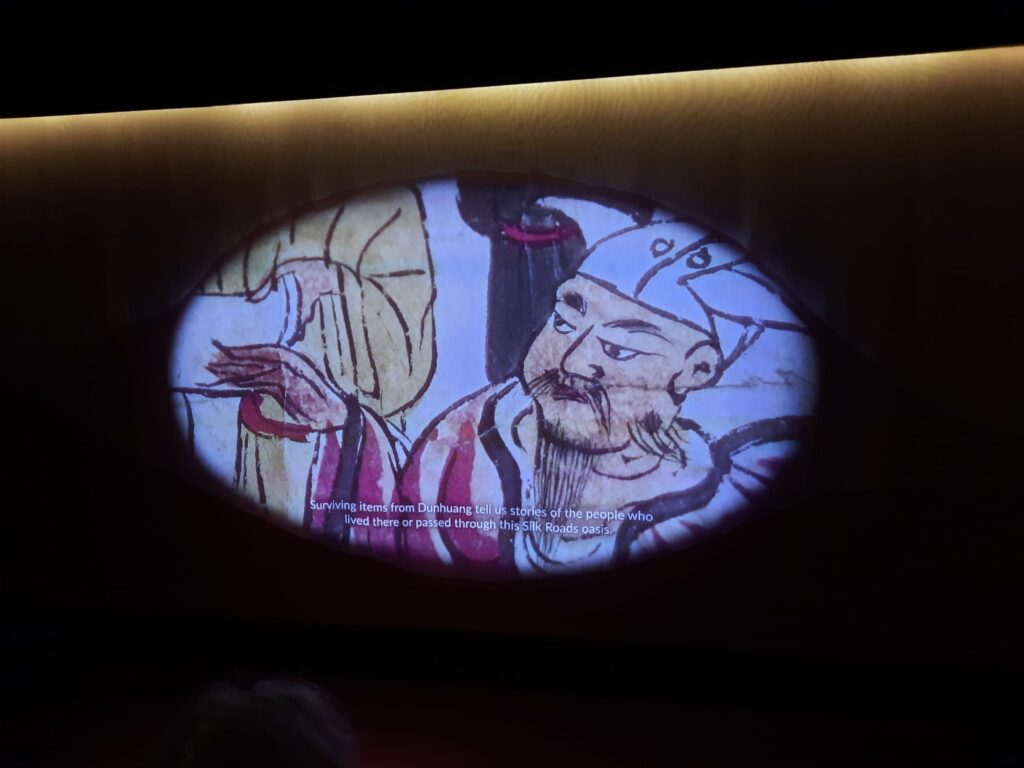

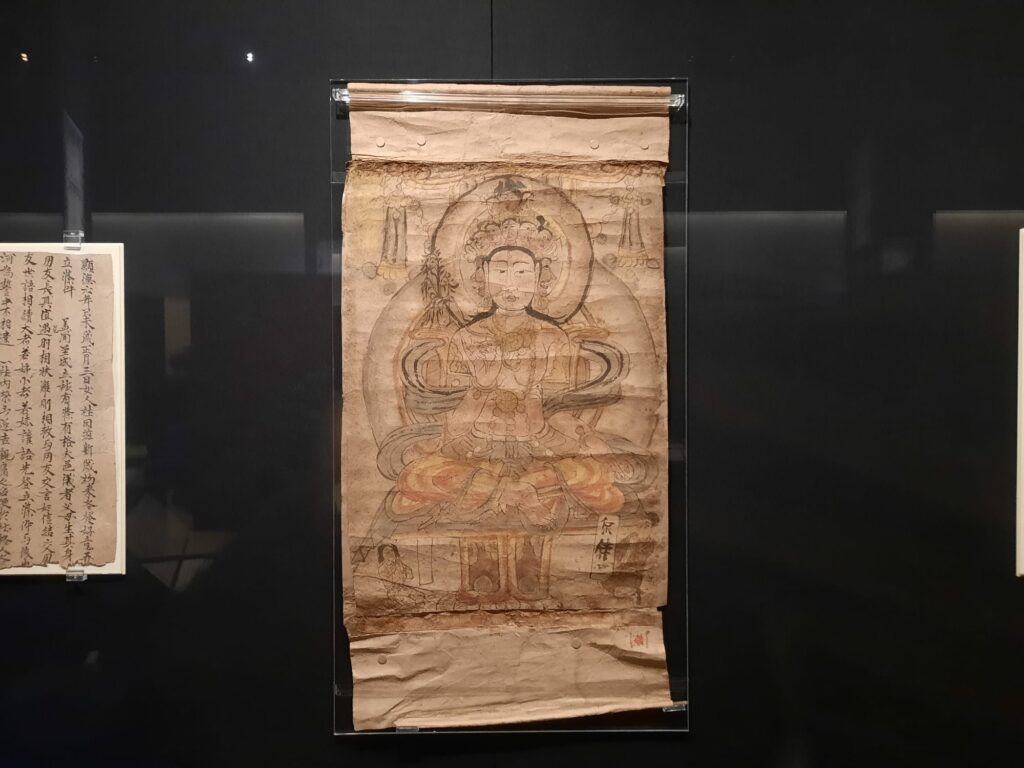

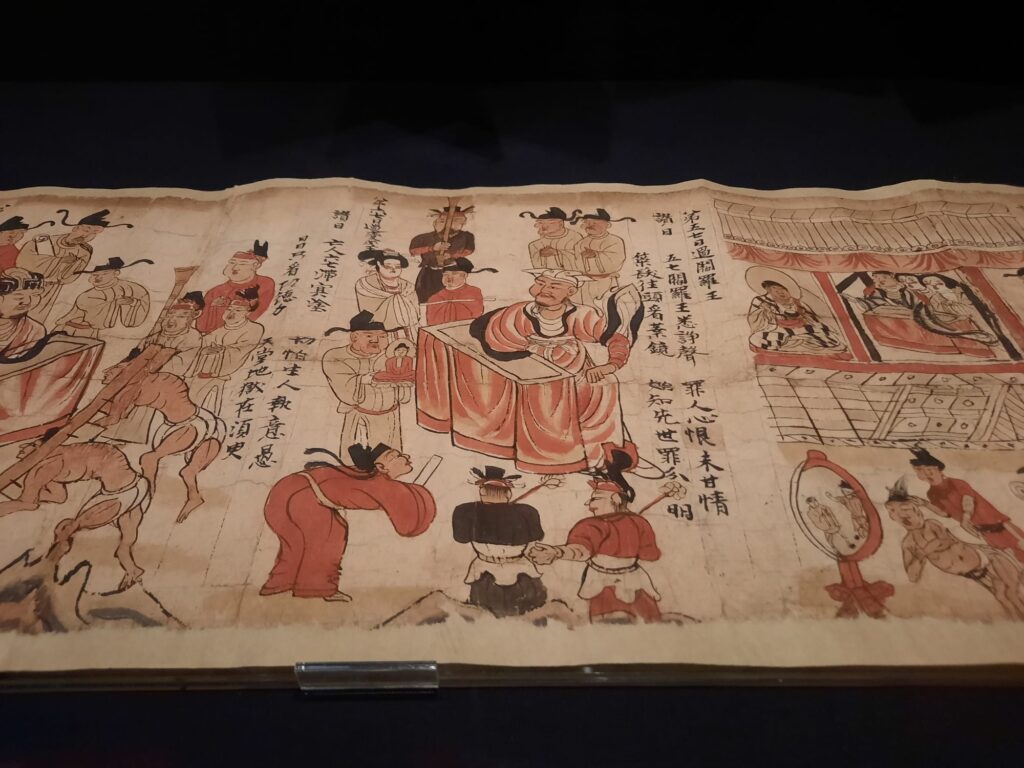

That place is Dunhuang. Dunhuang is today a city of almost 200,000 inhabitants in northwestern Gansu Province in China, which has been inhabited since around 2000 BCE. It is most famous for the Mogao Caves (also known as Dunhuang Caves or Thousand Buddha Grottoes/Caves) about 25KM distant from the city. Dunhuang lies at a strategic position, a natural crossroads for travel between East and West, Siberia, China, Mongolia, between desert and plains. This trade brought multicultural residents to Dunhuang. It also brought religion. The Mogao Caves began as spaces for Buddhist meditation and worship. Over time they became a place of pilgrimage, continuing in this function even as Islam reduced the influence of Buddhism in the region, and sea trade eroded the importance of the Silk Road and its trading hubs.

Treasures Make Their Way from Dunhuang to the West

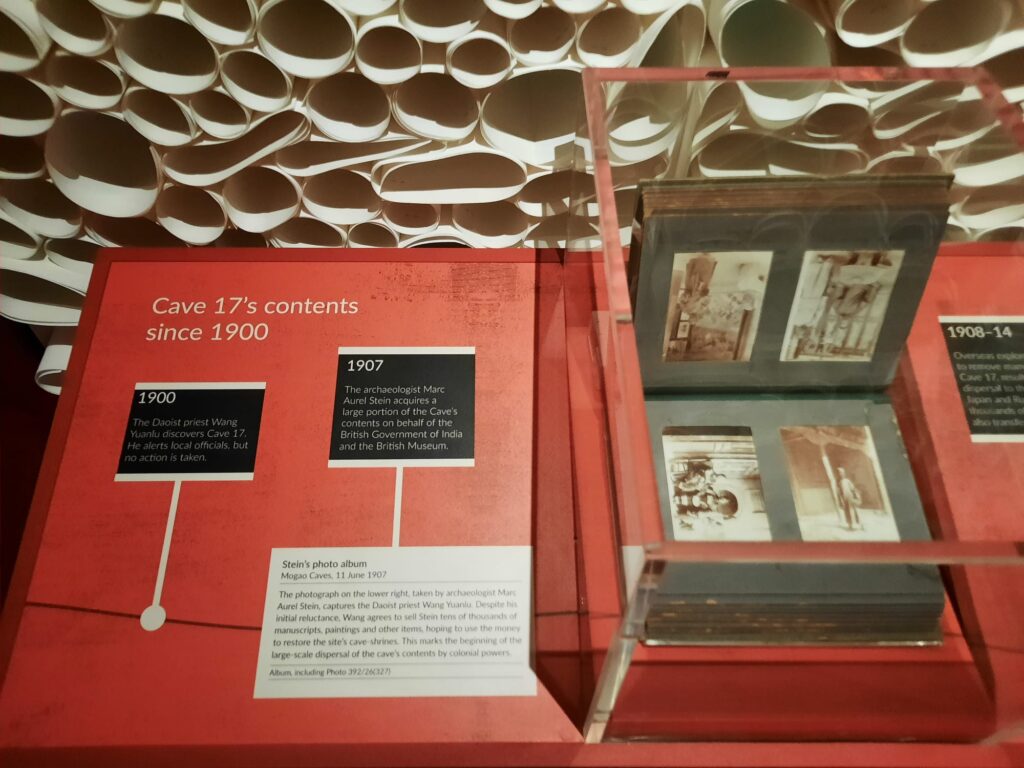

How is it, then, that a selection of treasures from Dunhuang now live at the British Library? It’s an exciting tale of discovery and exploration. Probably also a more problematic tale now than it was then. I’ll tell you a bit more about it and you can be the judge.

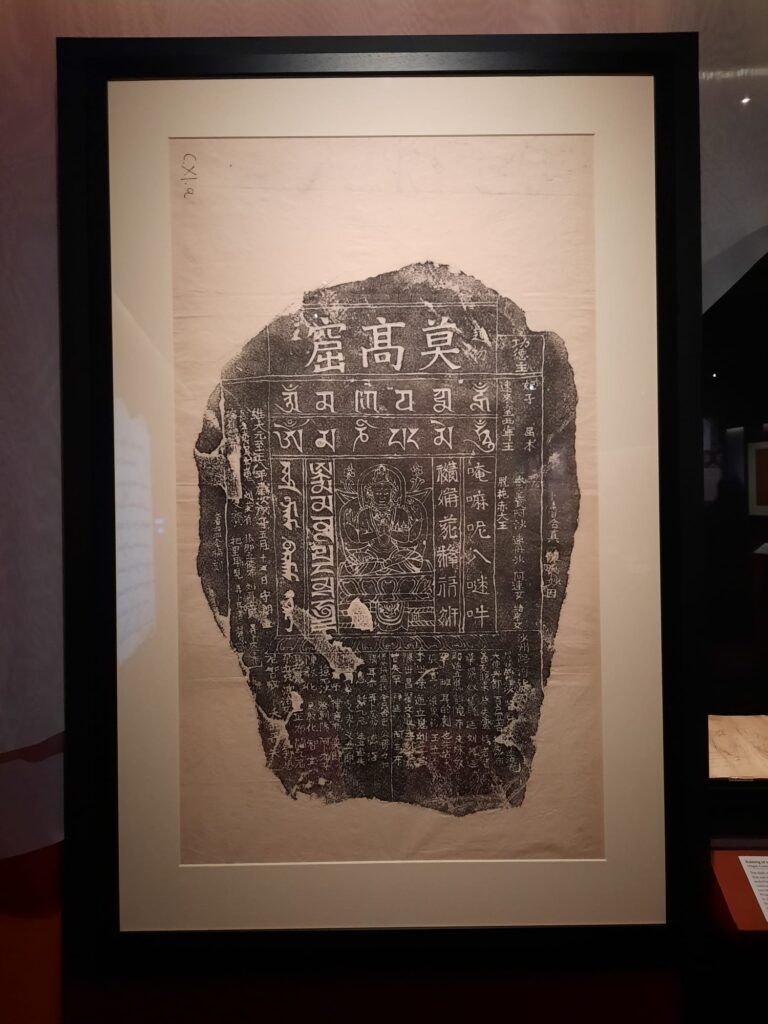

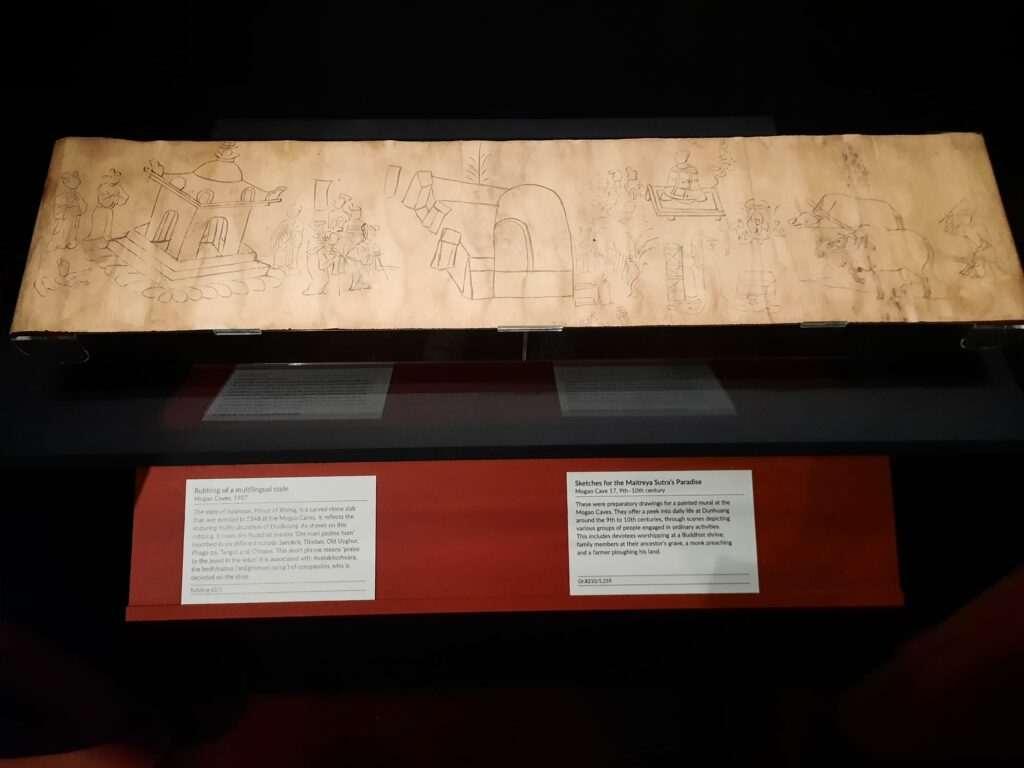

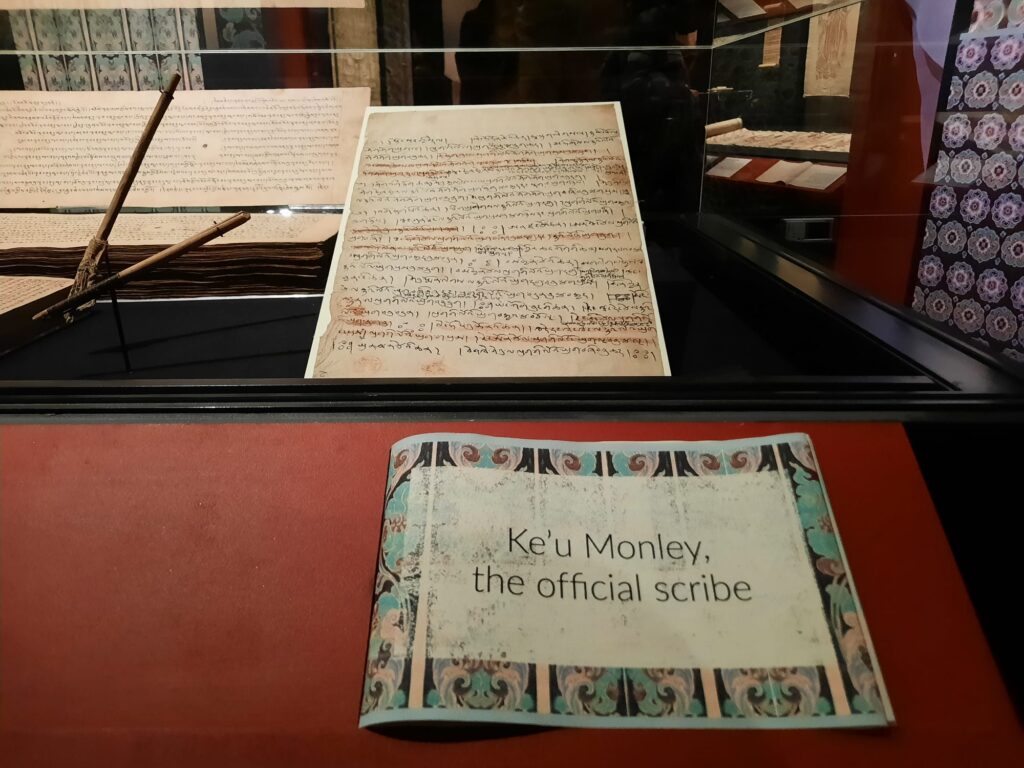

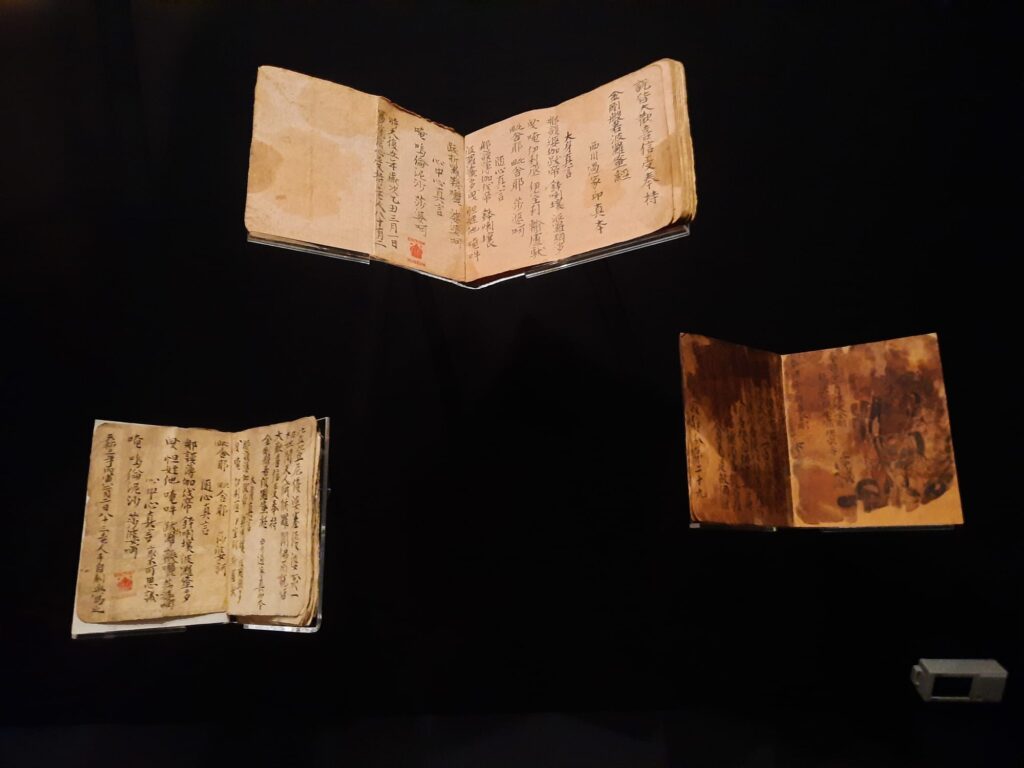

Time, then, to introduce two key people: Wang Yuanlu and Sir Marc Aurel Stein. The former was the discoverer, and the latter the explorer. Wang Yuanlu was a Taoist priest and itinerant monk. He was also the self-appointed caretaker of the Mogao Caves. In 1900, when doing some restoration of statues and paintings in one of the caves, he noticed a door. It led to what’s now known as Cave 17 or the Library Cave. It had been walled up in the 11th Century (presumably in response to some sort of threat) with about 50,000 objects inside, primarily texts relating to early Chinese Buddhism. Wang showed examples to several officials who showed differing levels of interest, but he was then ordered to block the cave off again in 1904.

Enter Sir Marc Aurel Stein. A naturalised British citizen born in Hungary, Stein worked in a university in India. Influenced by the work of Sven Hedin, who helped popularise the idea of the Silk Road (and was a Nazi sympathiser – we don’t like him), he was also an explorer and archaeologist. He made four major expeditions through Central Asia from 1900-1930. On his voyage of 1906-08 he travelled to Dunhuang. There he met Wang, and convinced him to sell some of the treasures of the Library Cave to fund restoration of the caves (Wang had already started to sell or give away items by this time). Later explorers including the French Paul Pelliot followed suit. Today items from Dunhuang are present in many museum and library collections. Stein’s purchases are divided between the British Museum, British Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, and the National Museum of India.

The British Library Explores Life in Ancient Dunhuang

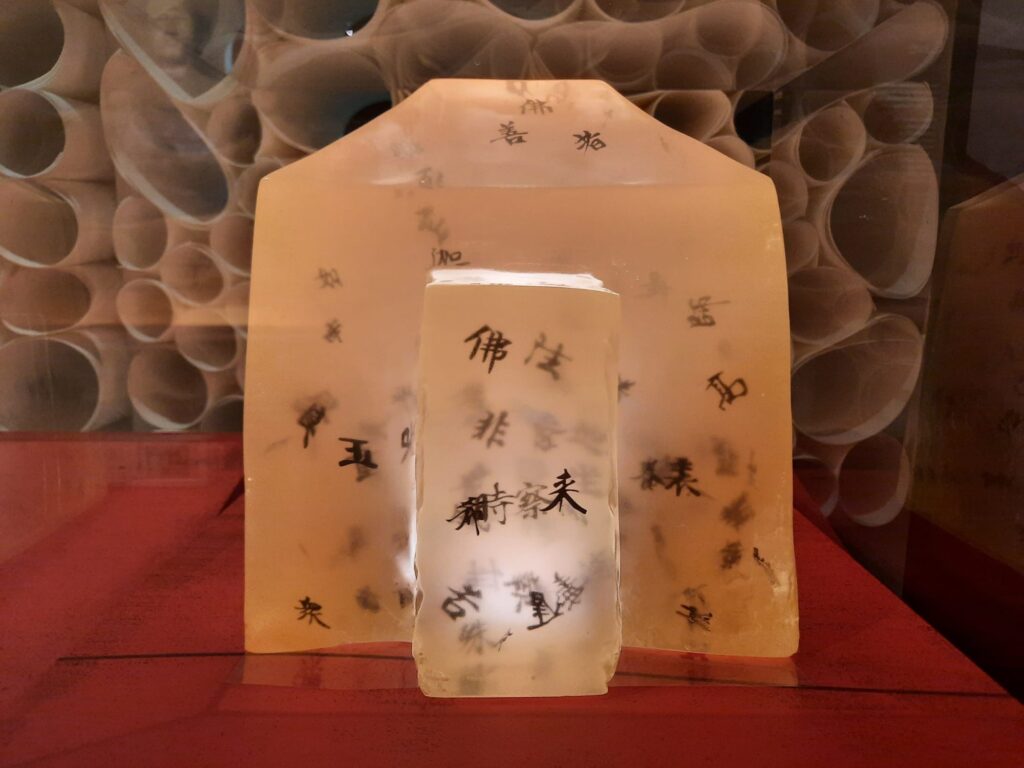

So, then. Knowing how these treasures came to live in the British Library’s collection, how have the curators brought them to life in this new exhibition? I would say, broadly speaking, that they have done this in two ways. The first is having some exceptional things on display. And the second is connecting documents to people’s stories.

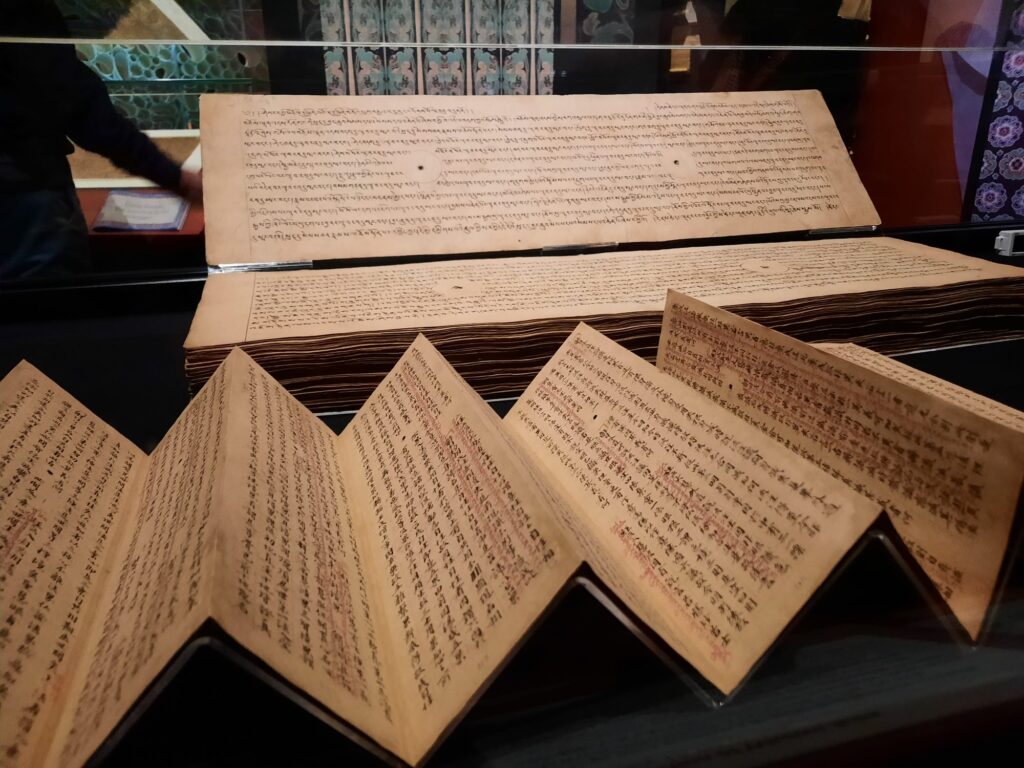

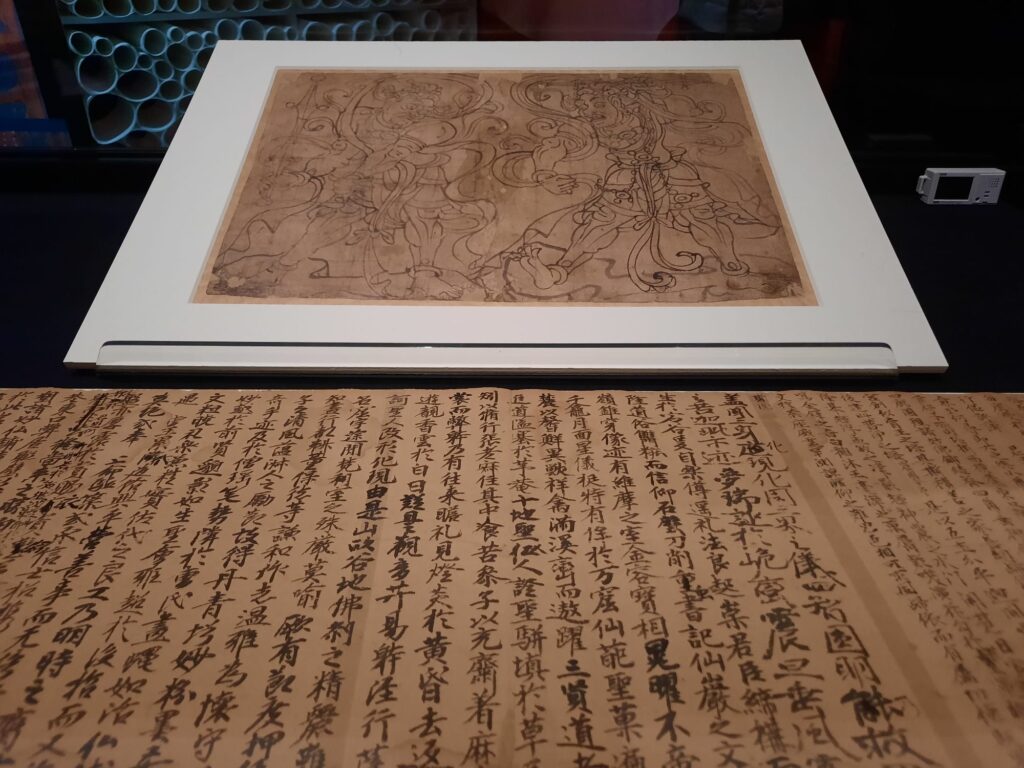

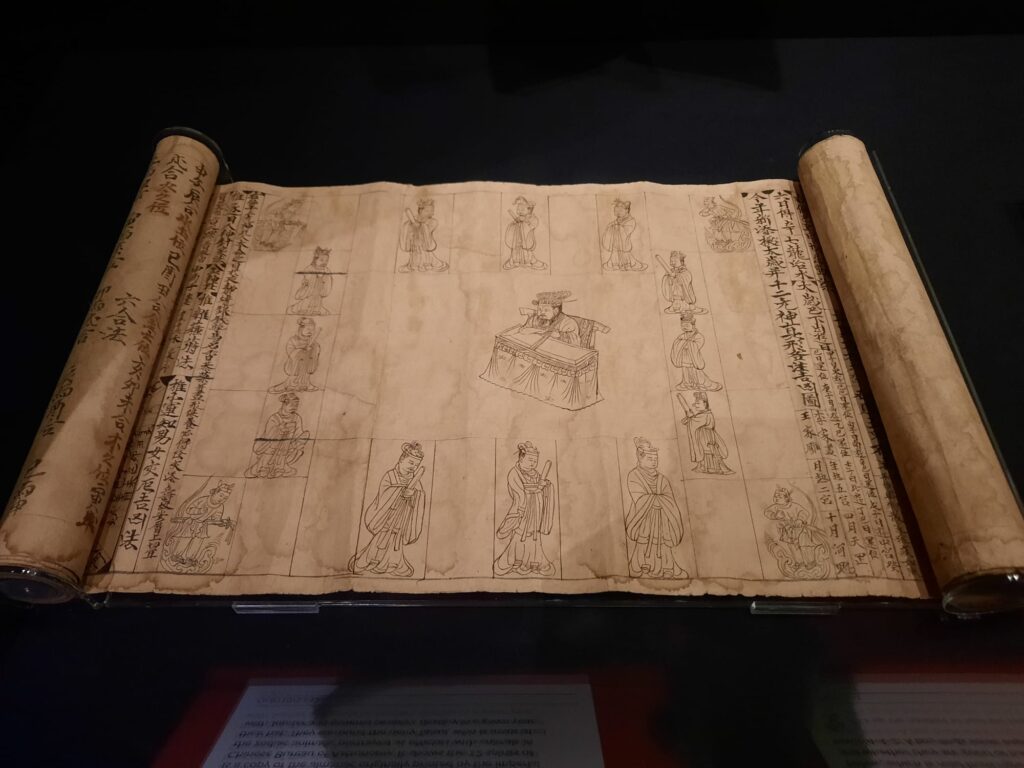

Let’s look at the first. The exhibition is actually fairly small. Just one room, with different sections which we will come on to shortly. There’s an introductory video as well as a couple of key objects. And then each section is supported by more objects, mostly documents. Within this small space, however, are some truly remarkable things, including:

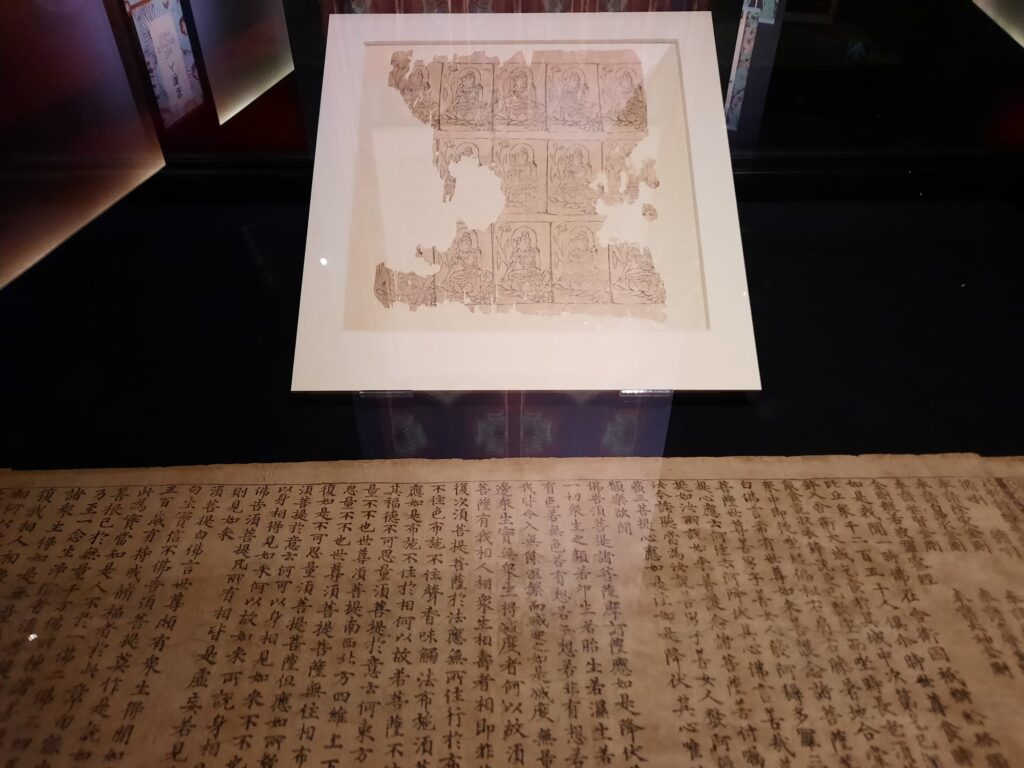

- The Diamond Sutra, the earliest complete and dated printed book in the world (9th century)

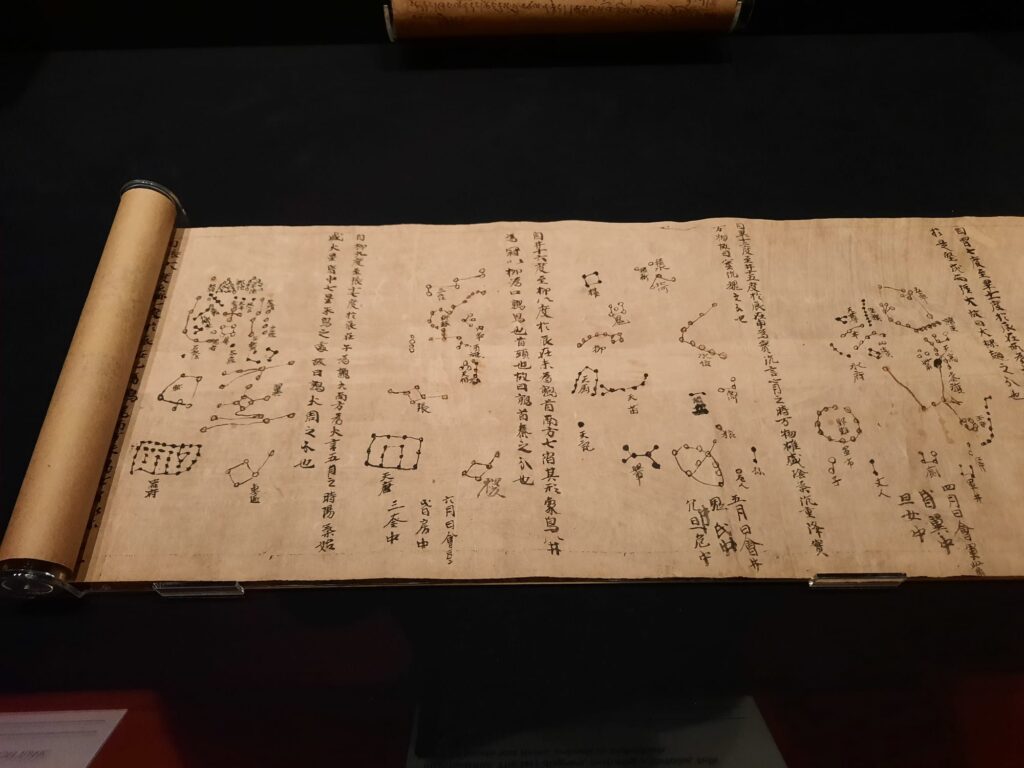

- The Dunhuang star chart, the earliest known astronomical map

- The Old Tibetan Annals, the earliest surviving historical document in the Tibetan language

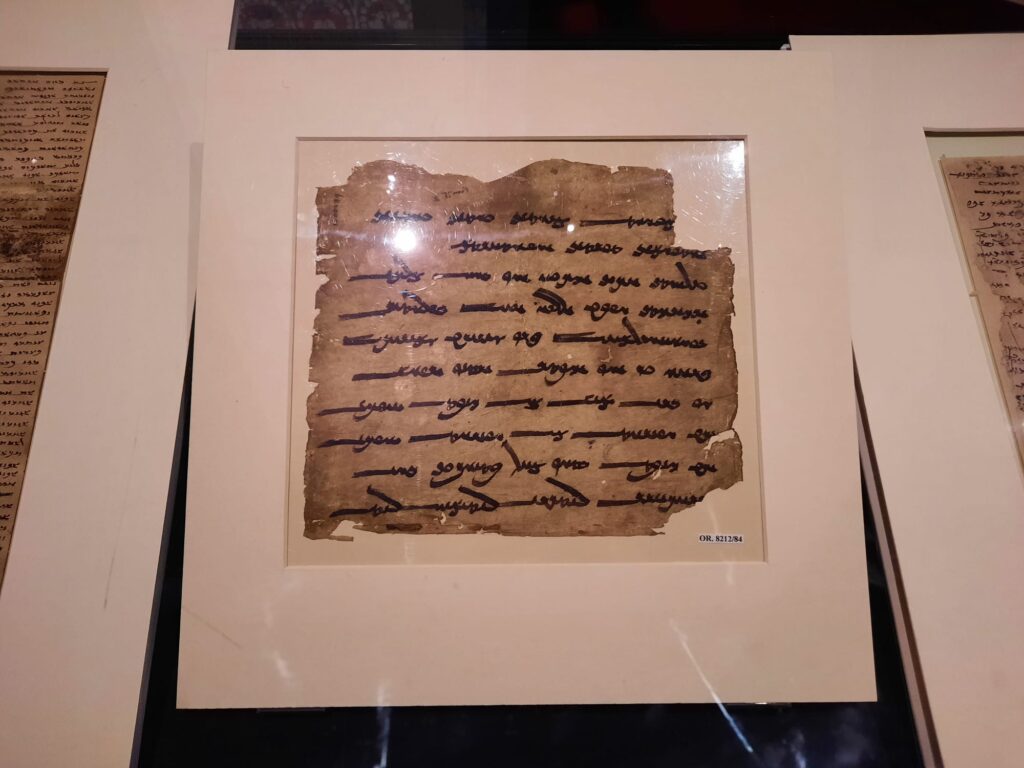

- The oldest surviving manuscript in Old Turkic script

- A 9th century manuscript fragment that’s almost 400 years older than any other Zoroastrian text

Wang clearly discovered a truly remarkable cache in the Library Cave. The British Library’s selection is only a fraction of the circa 50,000 item total. And I’m sure in both there is a fair amount of dross. But to glance around just one room and see so many ‘firsts’ is extraordinary.

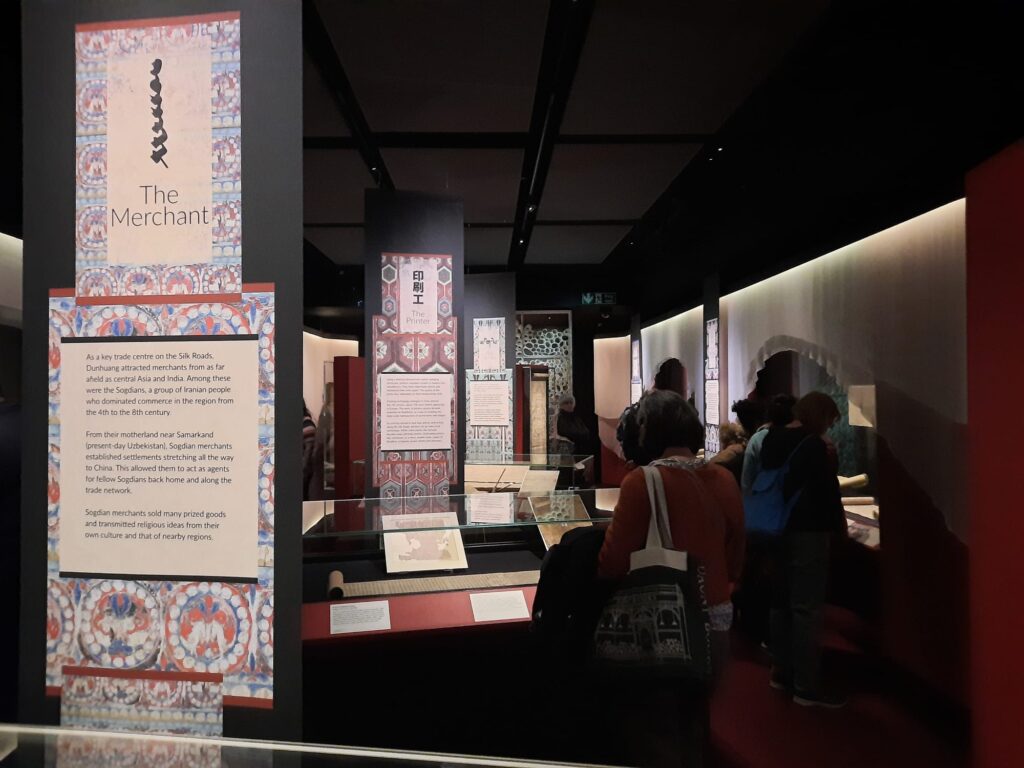

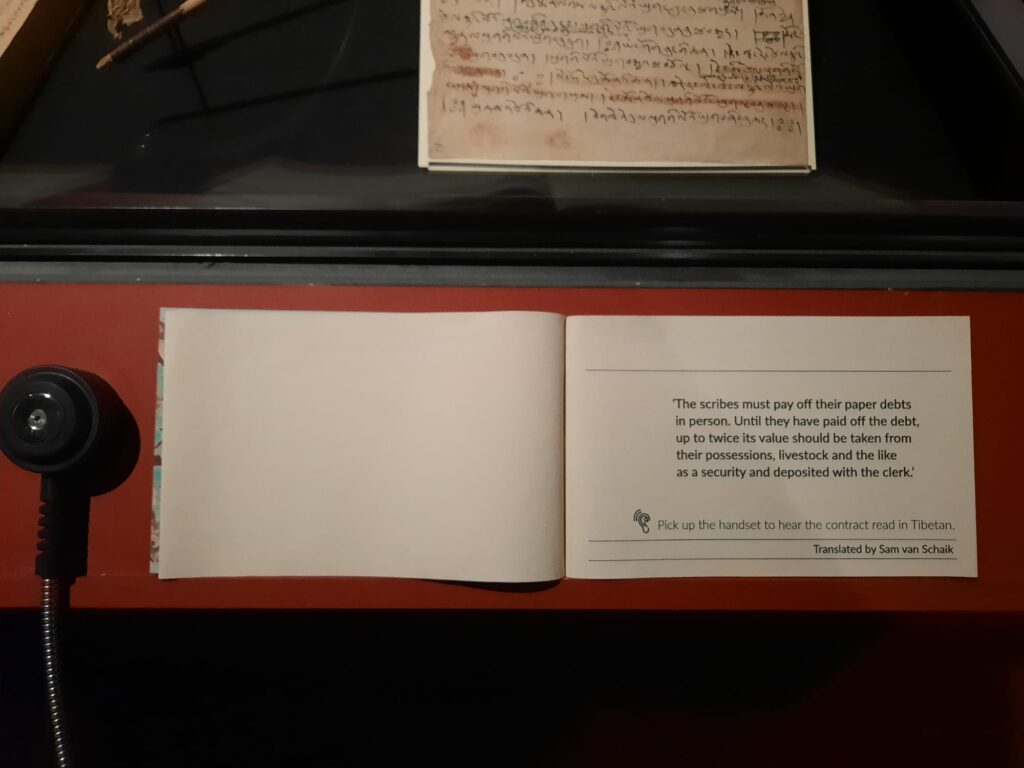

However, and it pains me somewhat to say this as a historian and museologist, documents are a little… dry, shall we say? British Library exhibitions normally do a good job of livening things up. They sometimes do this by including objects as well as books or documents. Or including multimedia aspects. Here they use character and sound. Each section of the exhibition embodies a person: The Diplomat, The Merchant, The Buddhist Nun, The Printer, and so on. On display are texts or objects that would have meaning for them. And most have a sound recording which connects us to places and people past. I never expected to hear love poetry read in Sogdian. Mostly because it was not a language I knew existed.

Why This Exhibition?

Since the 1990s, there have been efforts to digitally reunite the Dunhuang library dispersed more than a century ago now. The cache has become an area of scholarship in its own right as well as shedding light on aspects of history, culture and religion. What, I wondered, is the purpose of organising this exhibition and sharing Dunhuang and the Stein Collection with a wider audience? Is it just that it is interesting and lesser-known than it should be? Or perhaps a reminder that multi-culturalism and tolerance have been successful models for living for centuries? Maybe both? Or something else?

After spending time in the exhibition, I built up an enjoyable mental picture of ancient Dunhuang. It gave me a desire to visit a place I hadn’t heard of before. I learned about new peoples, the spread of Buddhism, and was reminded that, actually, lives in the past were a lot like our lives now. The technology may have changed, the world may be a bigger place, but we’re still preoccupied with work, love, complaints, and wondering if there’s a bigger meaning to it all.

It seemed a shame to me, in the end, that these wonderful treasures are here and not there. It’s one of those endlessly debatable situations. Wang had (at least according to what I’ve read) already started to disperse the collection. Stein purchasing part of it has preserved these documents: who can say if they would still be here otherwise, or not? And Stein purchased them, he didn’t take them by trickery or force. But were both Wang and Stein starting that negotiation from a place of equal knowledge and experience? Perhaps not.

In the event, though, they are here. And currently on public display. It’s well worth a visit just for all those ‘firsts’: if you have the time to really understand the characters of ancient Dunhuang while you’re there then even better.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang on until 23 February 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.