Francis Bacon: Human Presence – National Portrait Gallery, London

I catch one final blockbuster London art exhibition for the year in the form of Francis Bacon: Human Presence at the National Portrait Gallery.

A Little Seasonal Bacon

It’s been a busy few months for the Salterton Arts Review, not least on the exhibition front. The winter exhibition season always means a lot of things to see. And when you factor in Christmas plans, you have to be relatively selective in order to see your top picks. My final pick of the major exhibitions before heading away from London for some festive rest and relaxation was Francis Bacon: Human Presence at the National Portrait Gallery.

I know, I know. Last time I was at the NPG I said that on my next visit I really must see the rehung permanent collection. I’ve heard such great things about the increased diversity and inclusivity in the curation and accompanying texts. And I did a little better this time: I did go and see a few galleries before heading to the exhibition space. But the lure of temporary exhibitions is frequently too much for me compared to the reassuring, well, permanence of permanent collections. So that one is still a future ambition.

And why this exhibition? Well, I like a bit of Francis Bacon, for a start. I really enjoyed the last major exhibition of his work in London, which was only a couple of years ago. And for an artist who focused mainly on the human figure, however tortured and bestial, what better venue than the NPG? And so without further ado, let’s delve into the exhibition itself.

Francis Bacon: Human Presence

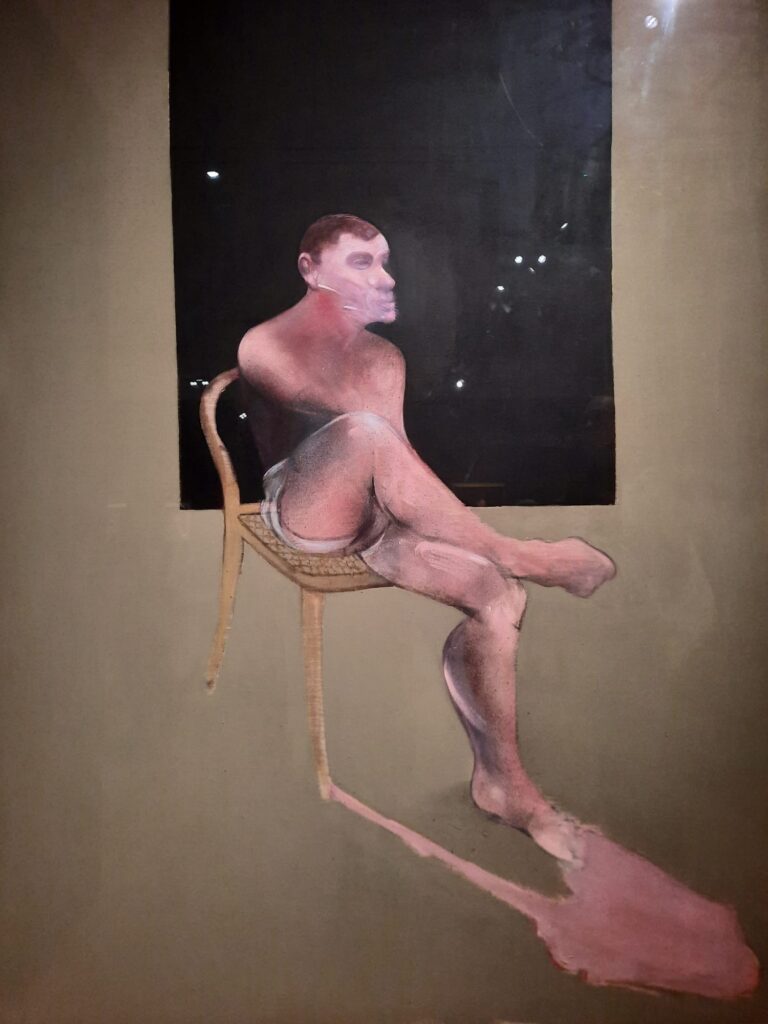

So as I alluded to, Francis Bacon: Human Presence is all about Bacon’s portraits. Which make up the majority of his work. Bacon, as a quick reminder, was born in 1909 in Dublin to English parents (Ireland was in any case still part of the UK at that time). He died in Madrid in 1992. In the interim, he built a very successful art career after making a start in painting in his late twenties. He was also a Soho regular, nurturing the bleak outlook on life which is captured in his paintings.

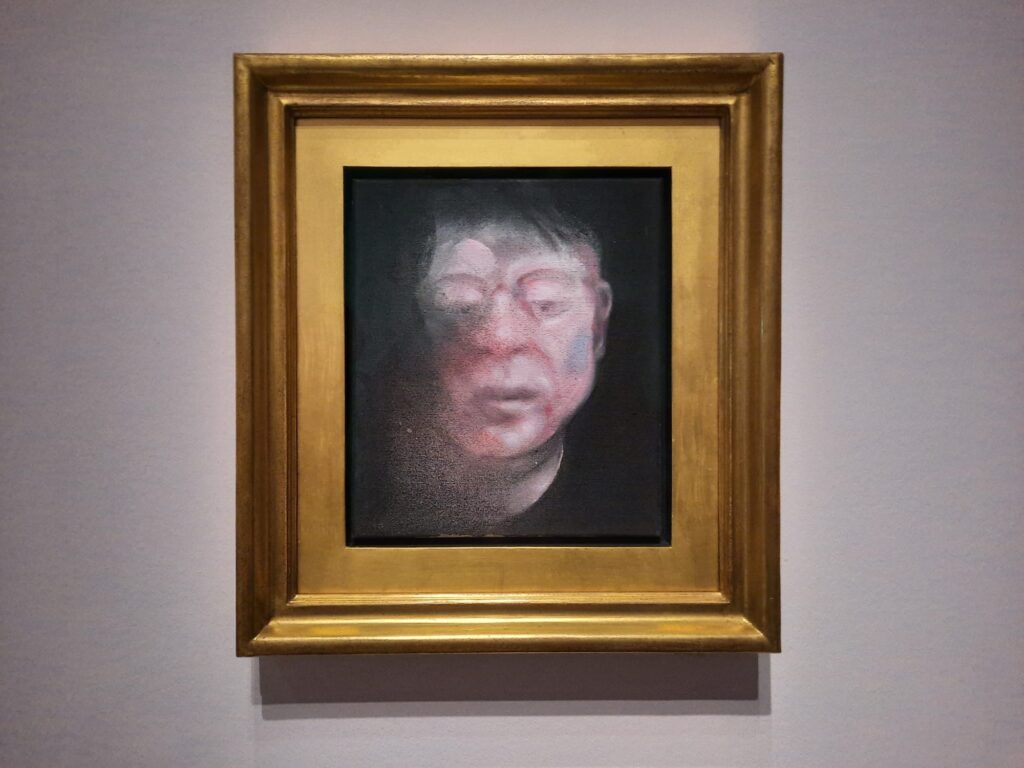

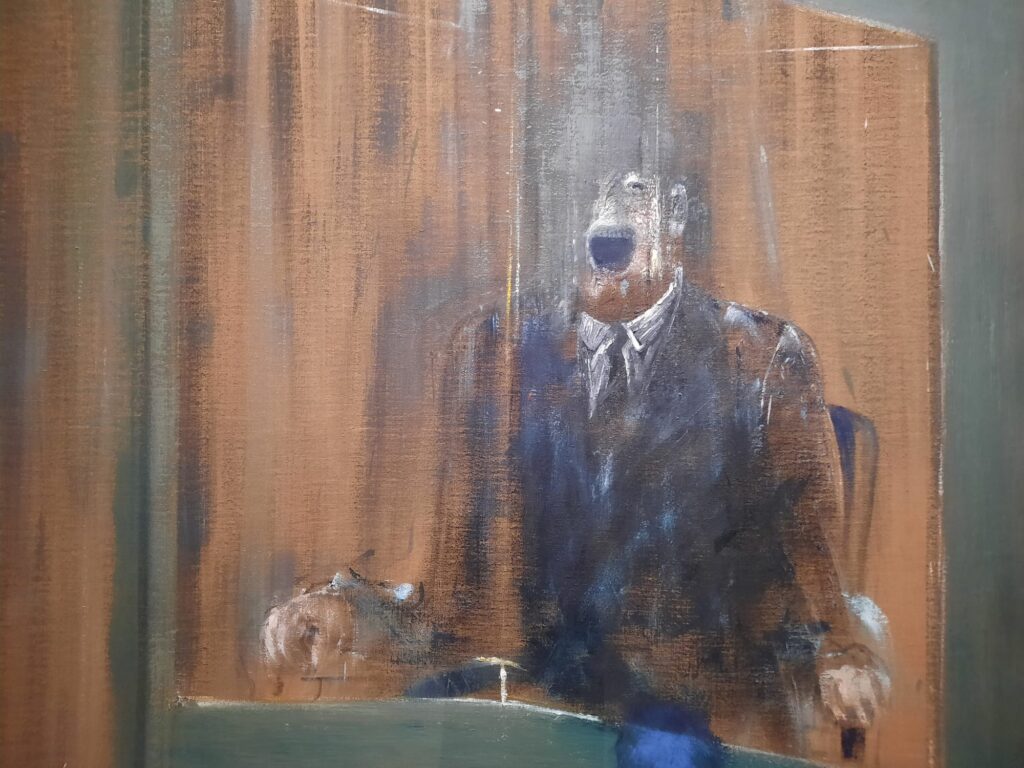

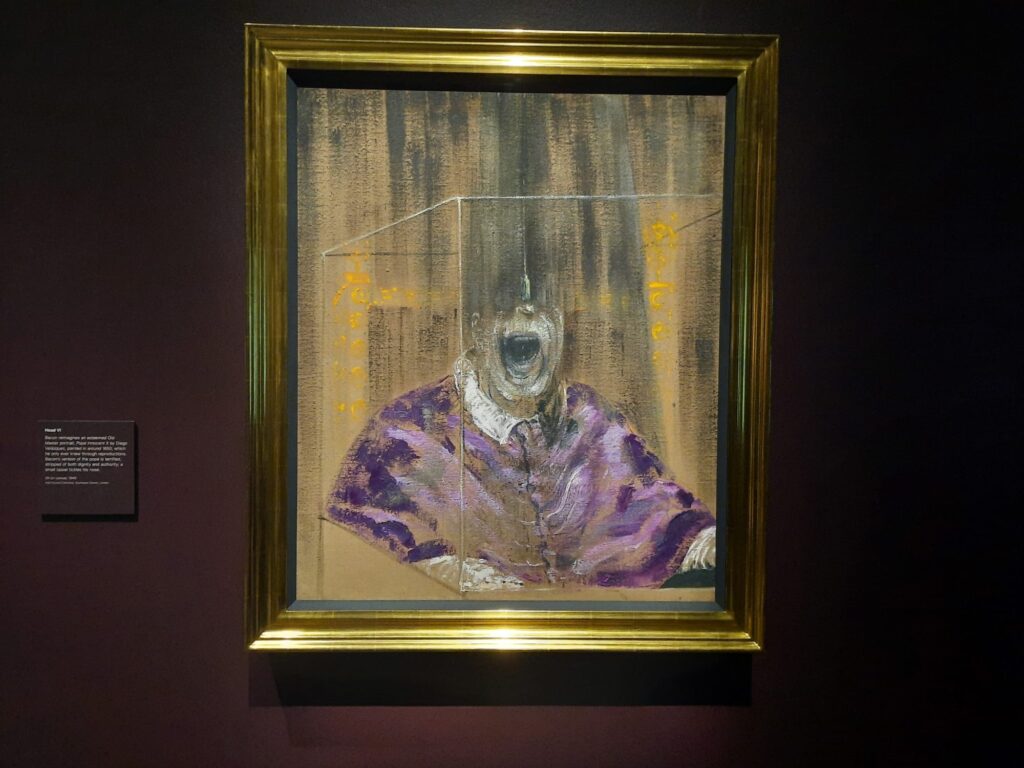

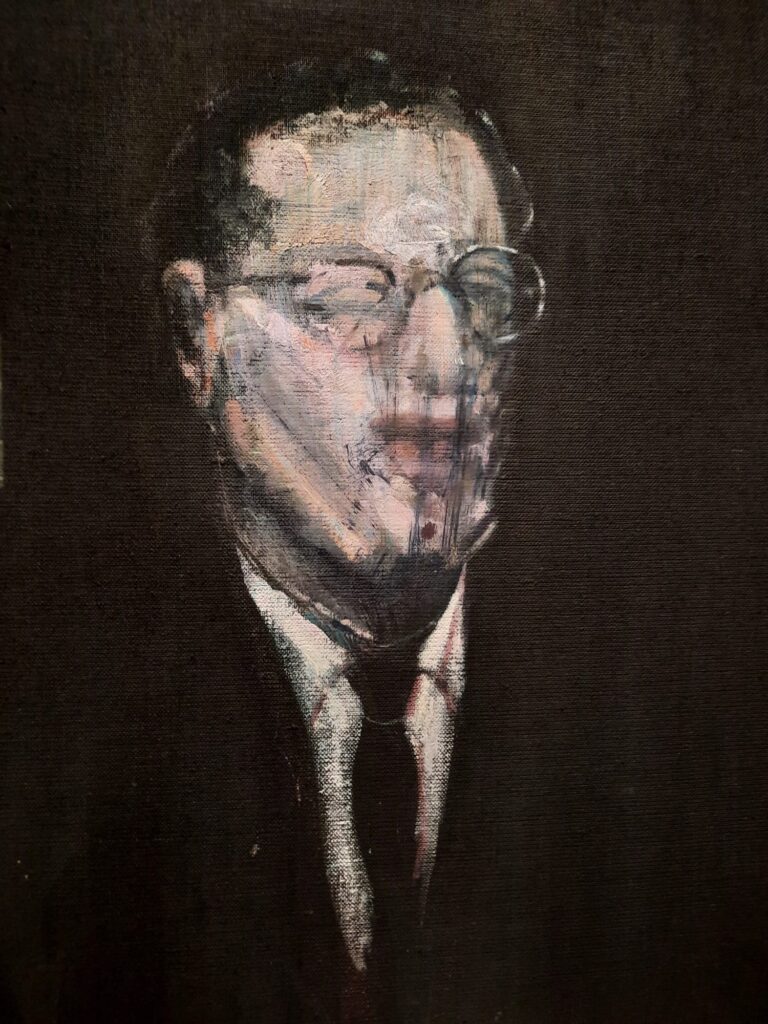

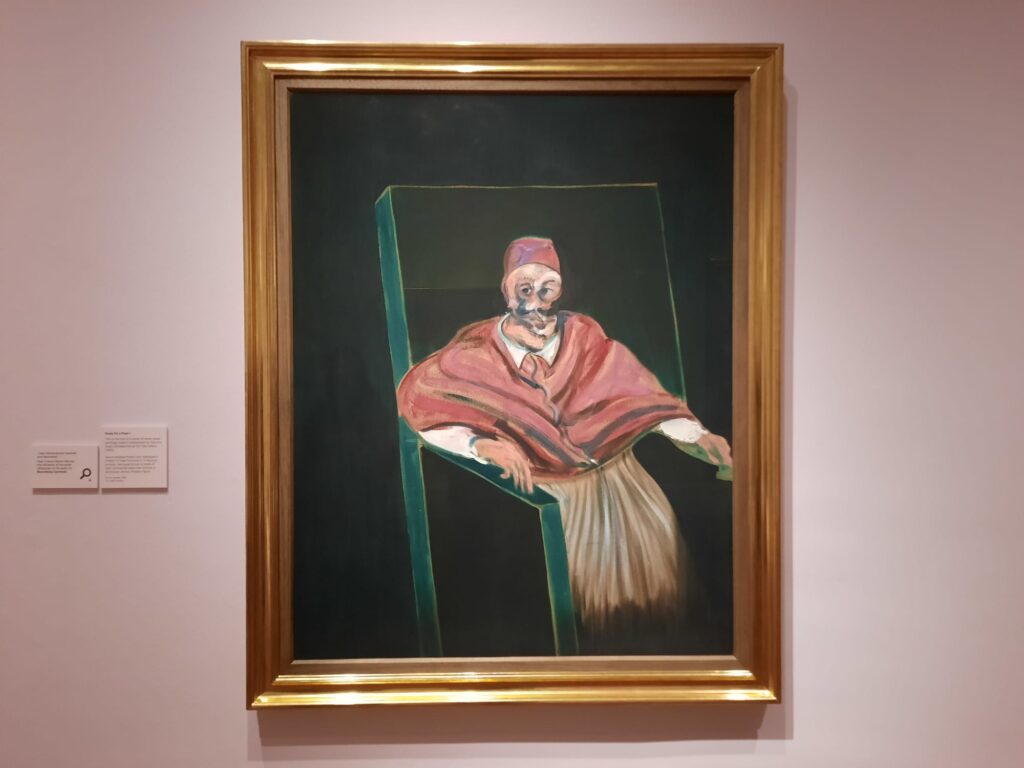

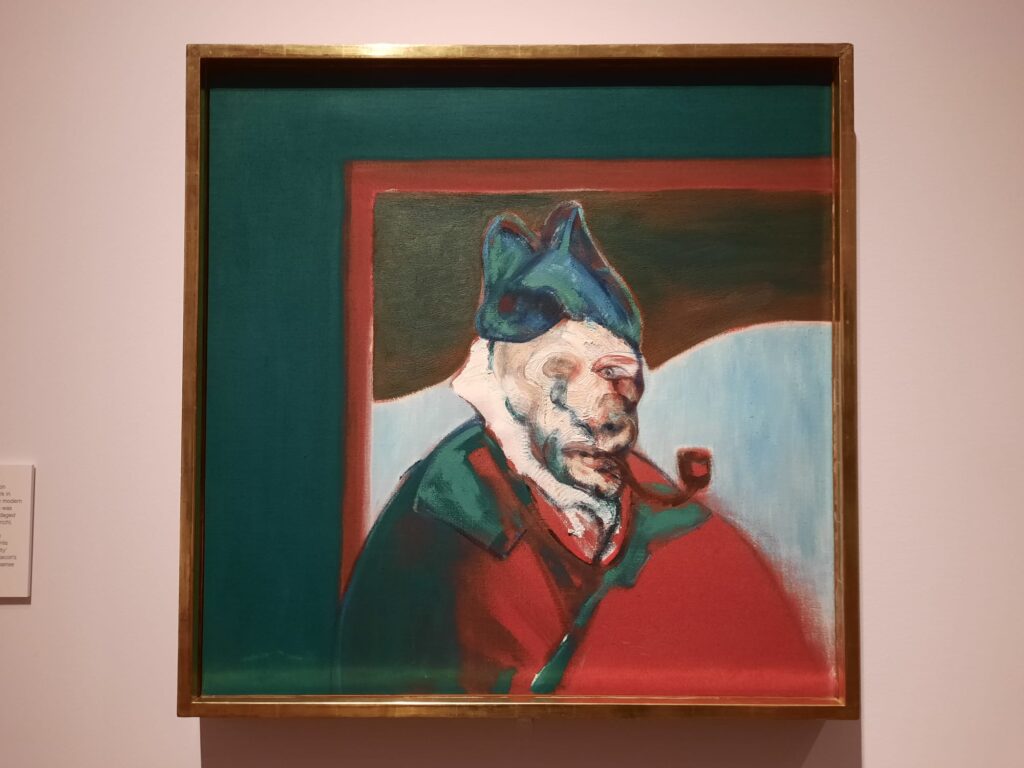

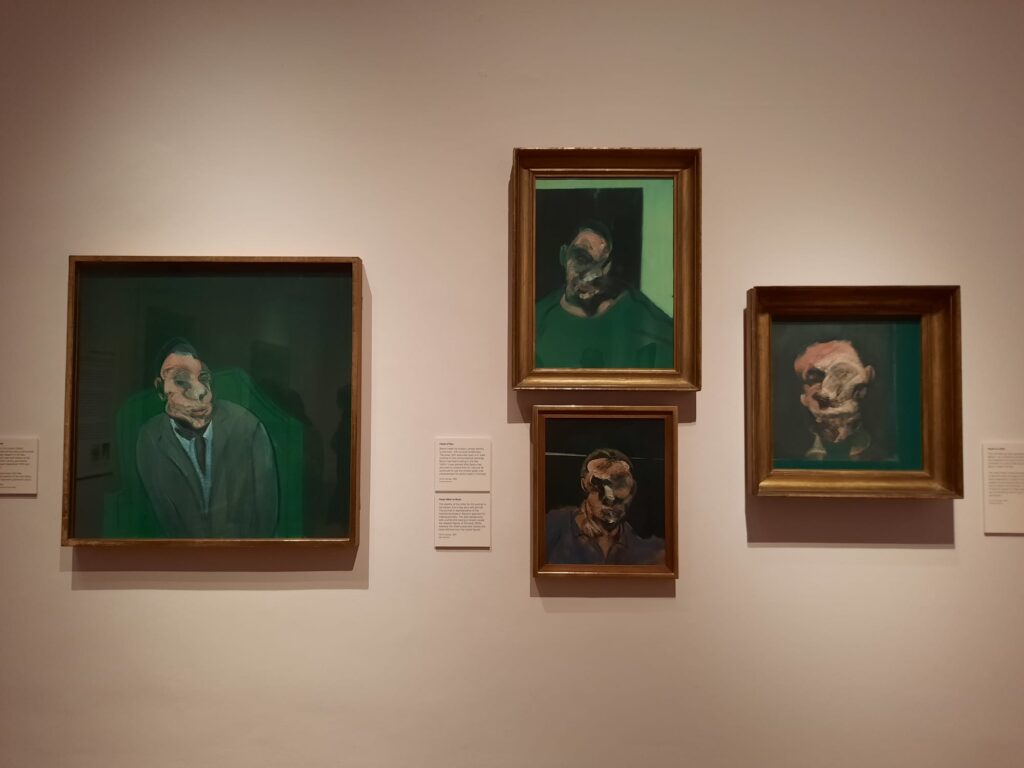

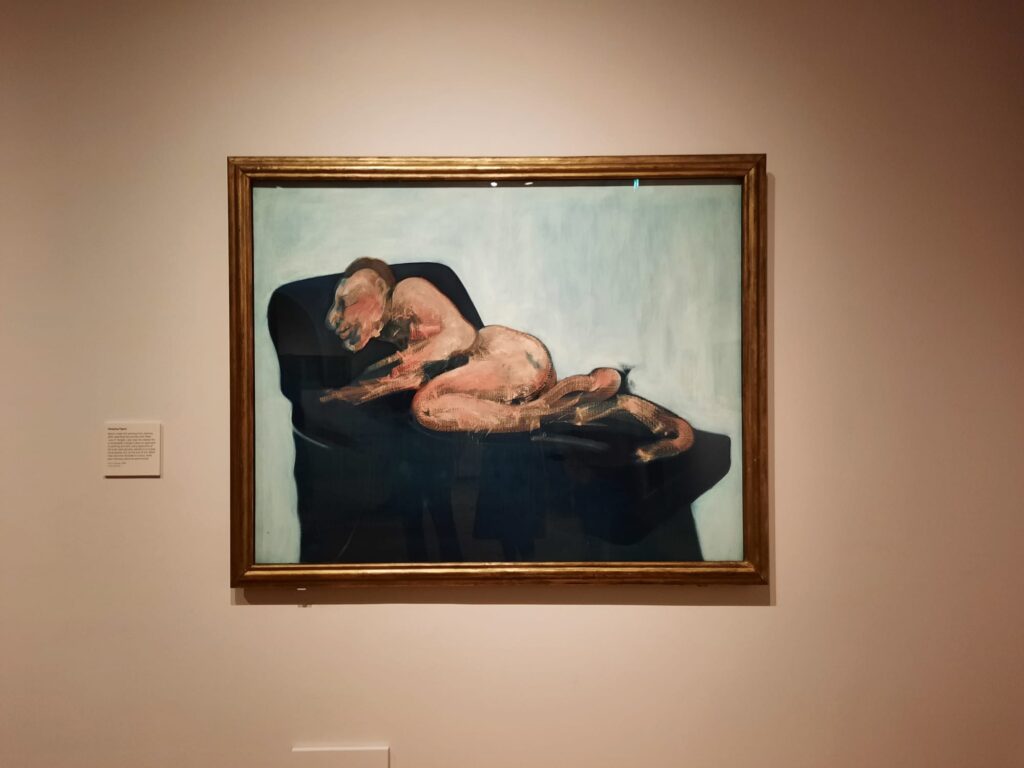

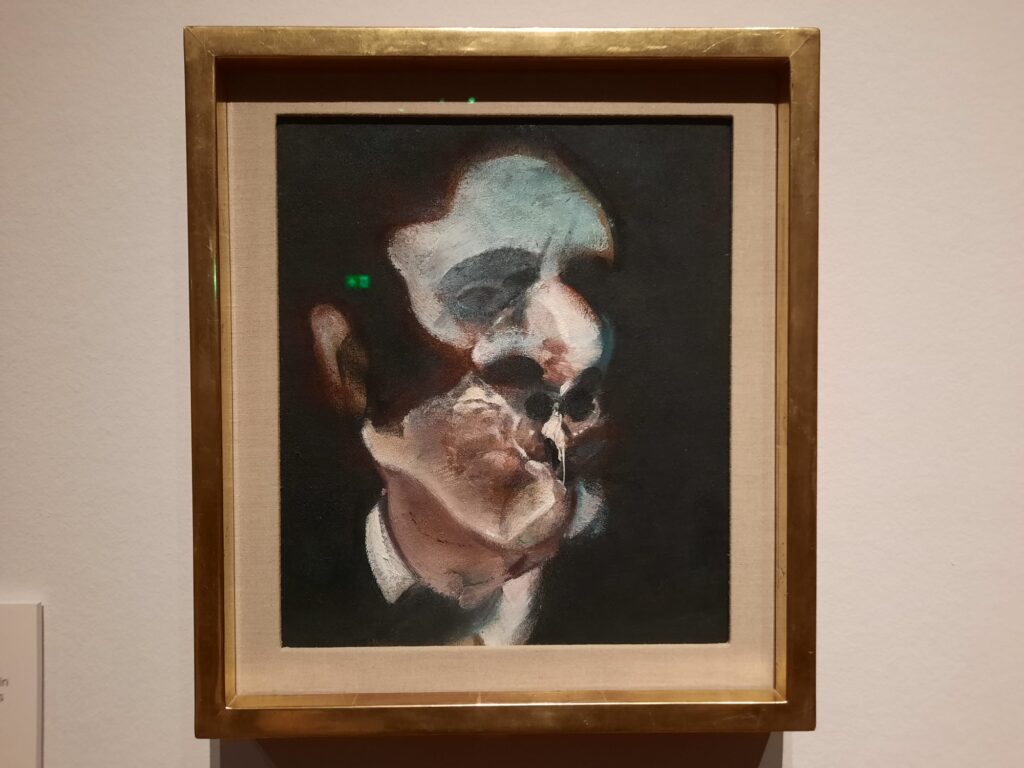

Bacon’s circle of lovers, friends and drinking buddies looks out at us from the walls of the NPG. As do a host of self portraits, patrons, and references from art history. It’s a big exhibition. And it starts with a self-portrait, before some of those popes Bacon is so famous for. It’s a way to set out some central themes of the exhibition. Bacon’s preference for painting from reference images rather than from life, for instance. And the resulting distance created on the canvas. Bacon’s portraits are elusive. Even in their titles: the endless Studies For… are a ruse – finished works masquerading as something else. From the beginning, we see that we will need to dig our own way beneath the surface to understand what this artist is conveying to us.

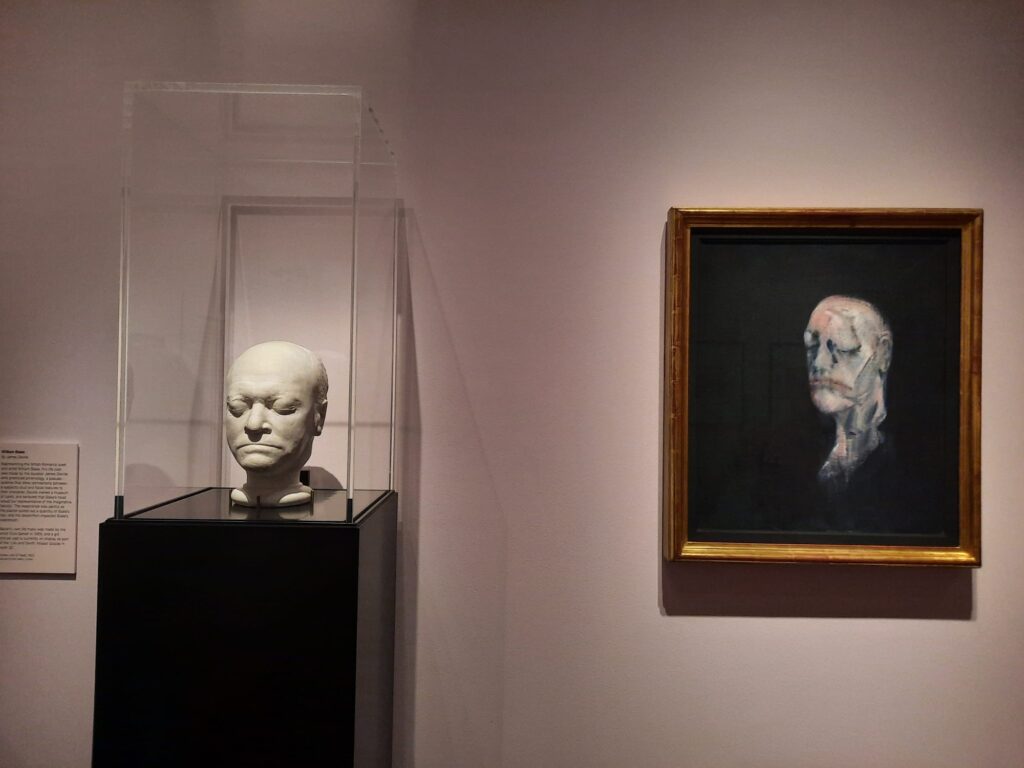

What we also see from the outset is what a magpie Bacon was. How he stored images away, only to pull them out at the most unexpected moments. There are even one or two paint-splattered examples on loan from his famously cluttered studio. It seems a curious thing that Bacon never saw some of his most famous reference works in the flesh. But the further we get into the exhibition, the more it makes sense. It was about finding the perfect image or disparate details to unsettle the viewer, create a feeling rather than capturing a likeness. No comfortable society portraits here, folks.

A Surfeit of Bacon?

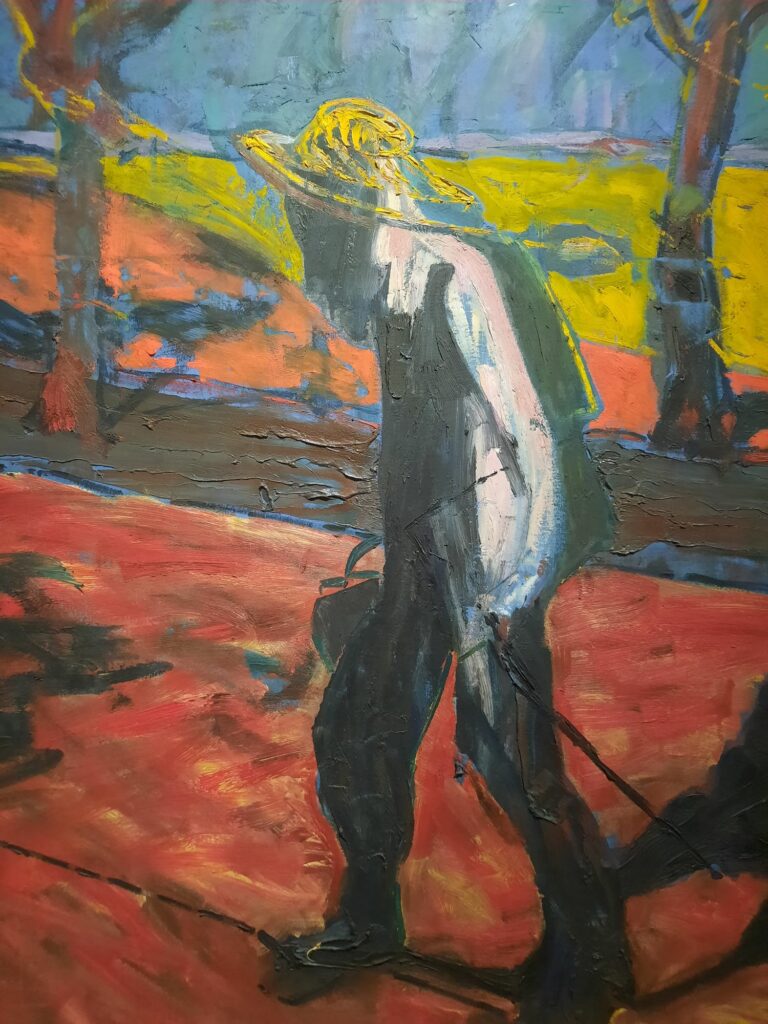

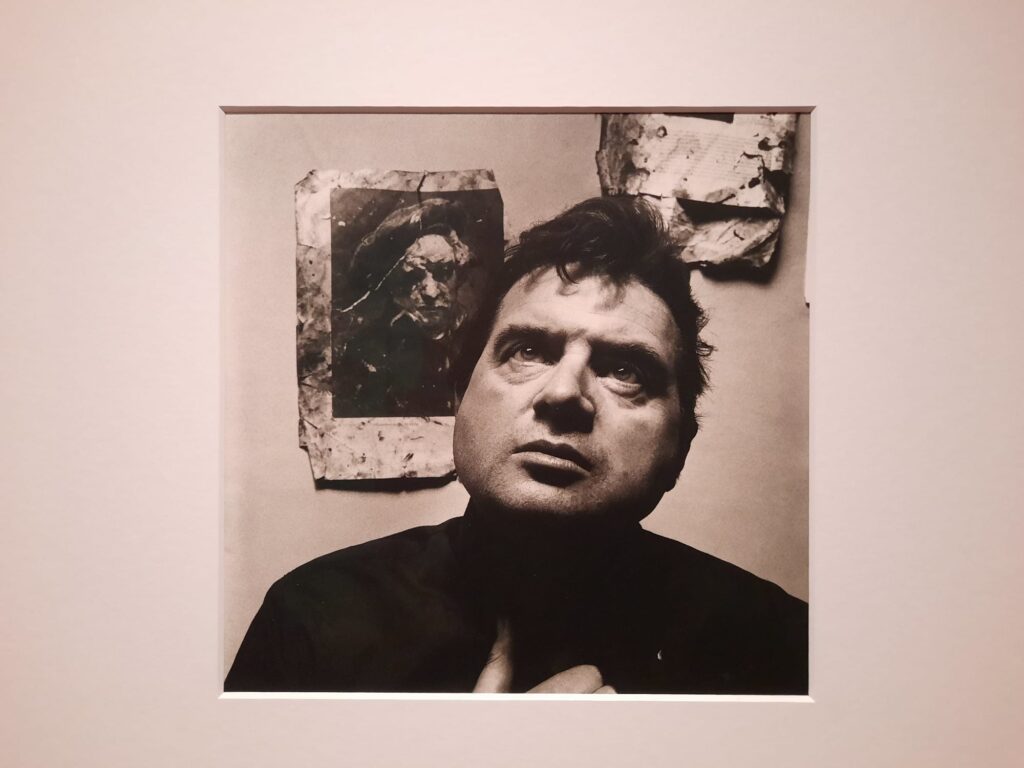

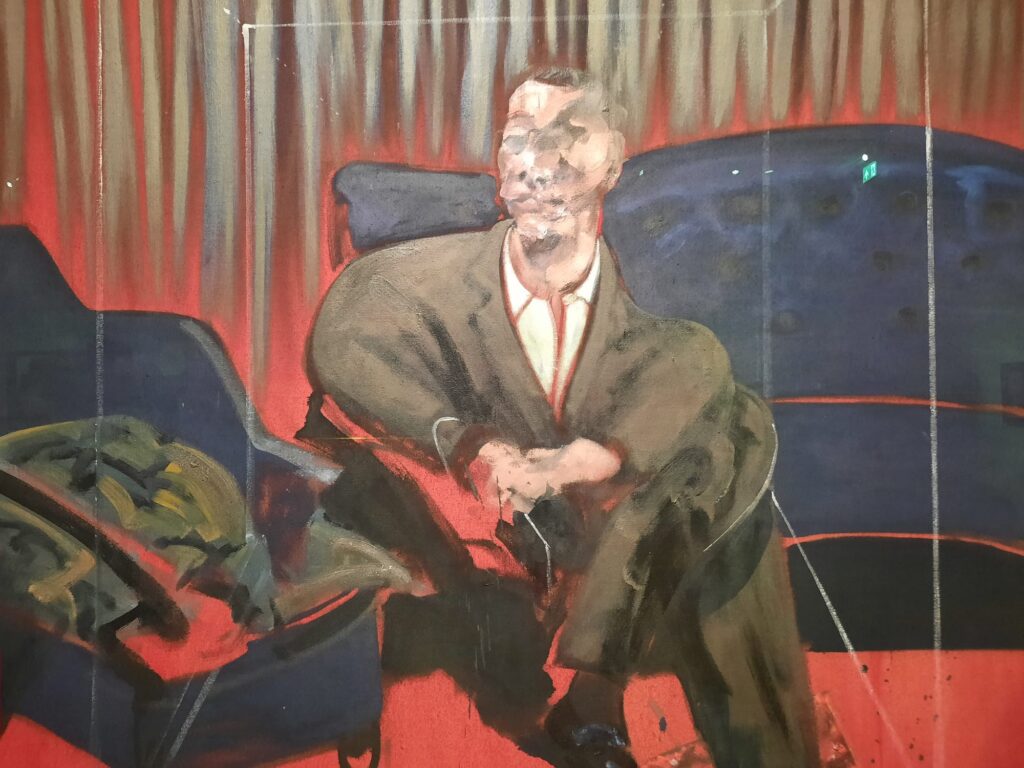

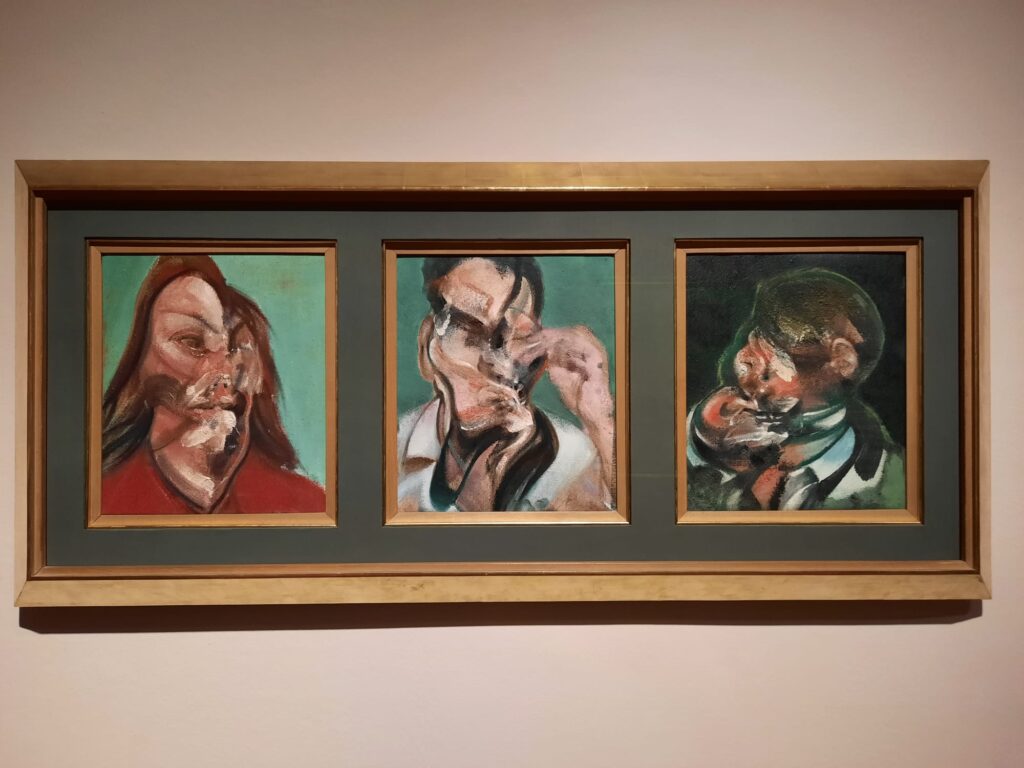

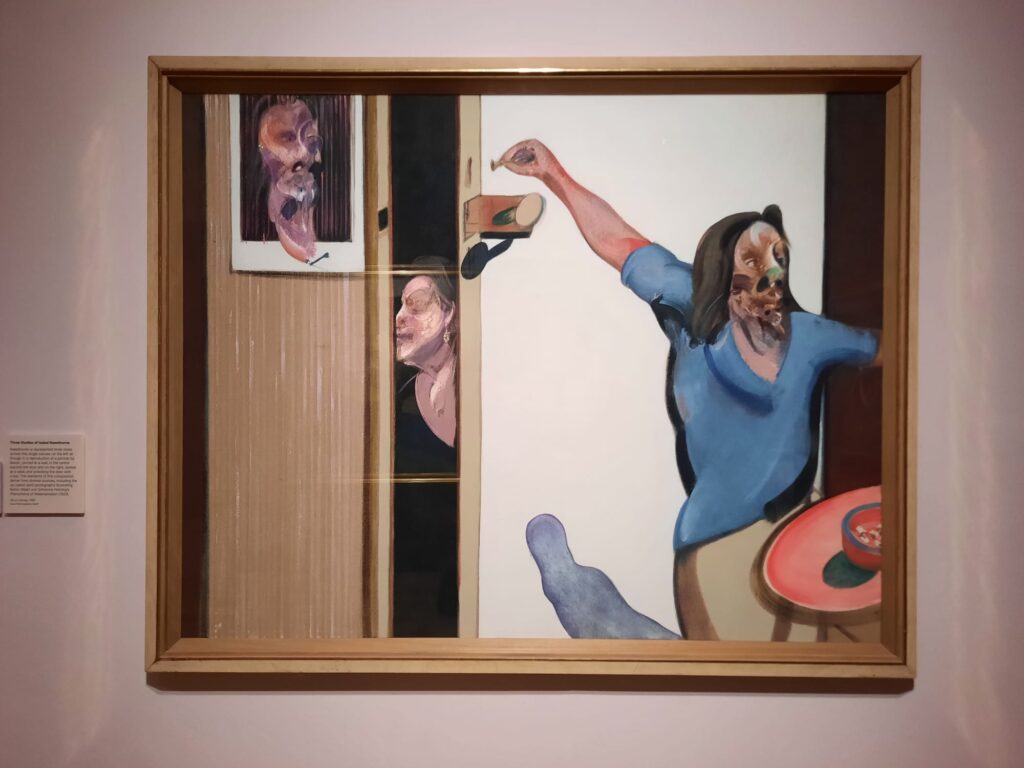

One thing about this exhibition is that there’s rather a lot of it. I’ve described the opening couple of rooms, with a self portrait and some popes. Then we have a couple of portraits of patrons (the Sainsburys). Next up is a section where Bacon riffs on Van Gogh, Velasquez, William Blake and Rembrandt. On its own, this would already be a pretty decent exhibition. But wait, there’s more! We’re only about halfway through in fact, with an entire second section where the paintings are arranged by sitter. Peter Lacy, Henrietta Moraes, Lucian Freud, George Dyer, and so on. Plus there are some self portraits and photographs of the artist by different photographers.

By the end, it’s almost a surfeit of Bacon. Especially as the curatorial vision isn’t always clear. The main point is to present portraits by Bacon. Fine, I’m with you so far. But really, most works by Bacon are portraits, in one way or another. Or are human forms, in any case (aside from those that veer more towards animals, as we saw last time). The introductory text promises the exhibition will chart the development of portraiture in Bacon’s work. Arguably the first half of the exhibition does this. The second, subject-led half a bit less so. And the riffs on Old Masters become even more of an aside in this context.

I do sometimes suspect that London’s larger institutions fall foul of a desire or obligation to fill big exhibition spaces. You’ve heard me complaining about endless exhibitions at Tate Britain before now, for instance. Is this the case here? Perhaps. Or perhaps there is a curatorial vision that didn’t quite come through during my visit. In either case, I wonder if a judicious trim might have helped this exhibition to really hone in and say something new about Francis Bacon?

Insights, Nonetheless

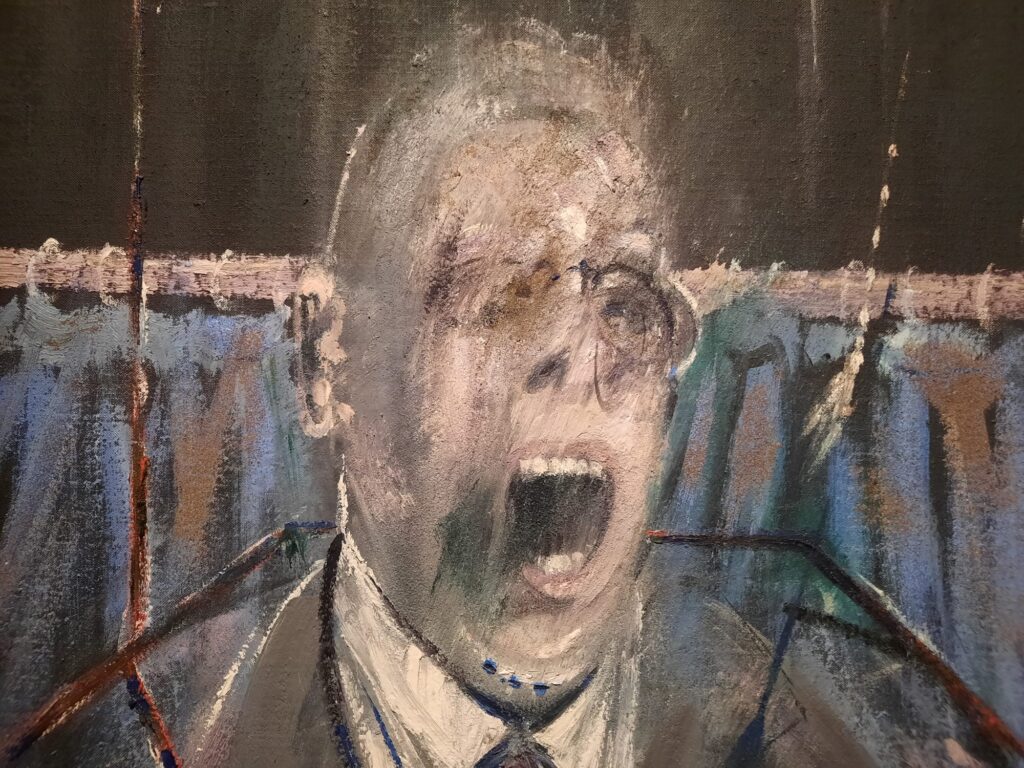

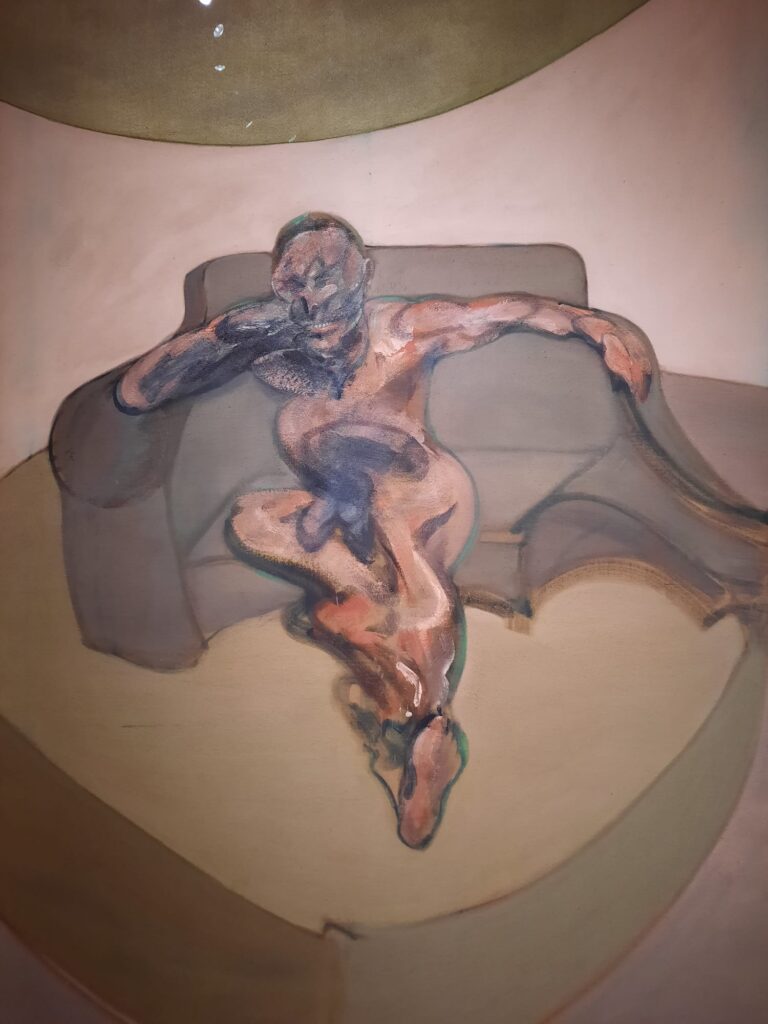

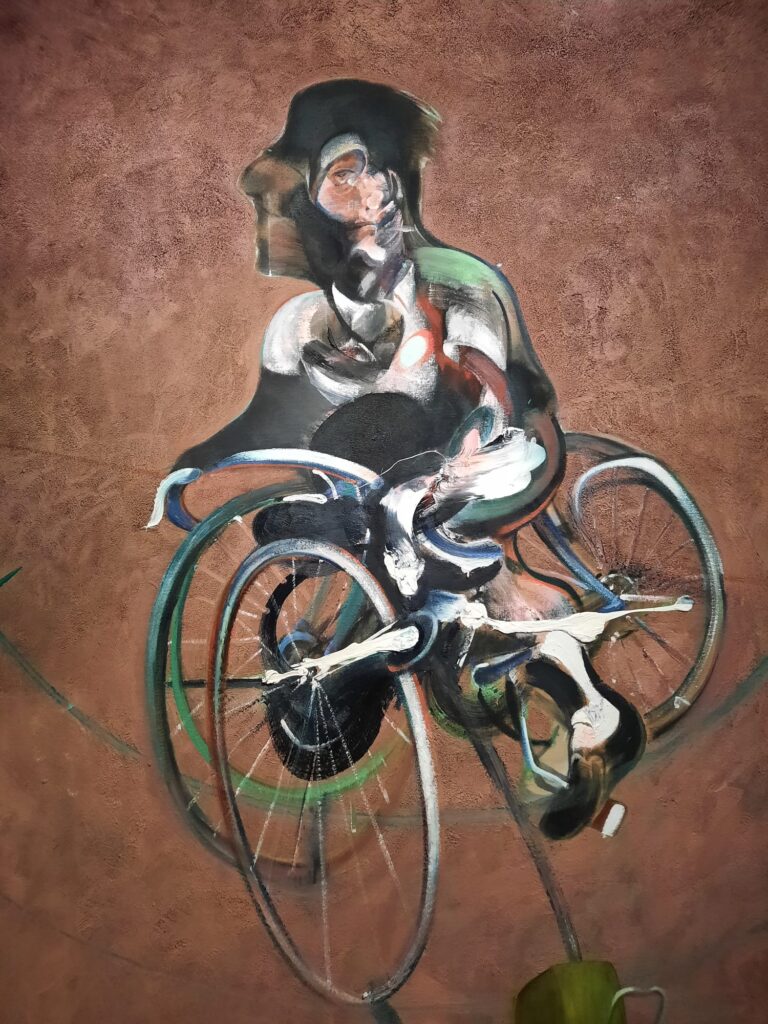

The thoughts I’ve just outlined perhaps come across a little harshly. I did enjoy this exhibition. Firstly I like getting up close to Bacon’s paintings. There is something very pleasing in their texture. I like all the sparsely applied paint, the rawness of the unprepared canvas showing through. It matches the uncomfortable figures perfectly. Bacon, like his sometimes friend Lucian Freud, was firmly a figurative painter in an age of Abstract Expressionism. He was his own man, and it comes across looking at the very distinctive visual language that unites the works on view.

This exhibition also gave me a newfound appreciation for Bacon’s dialogue with art history and other artists. Connections to Picasso struck me in particular. As I wandered the exhibition I found myself thinking about the tortured, distorted faces as an extension of Picasso and Braque’s Cubism. Where the Cubists depicted objects from different angles simultaneously, Bacon goes one step further. It’s like he sees through and into his subjects, and brings everything to the surface at once. Their face, skin, teeth, thoughts, minds, deepest shames, vices, lonely deaths. Nothing escapes him, it’s all there for us to see. Another fleeting realisation was that, like Picasso, Bacon’s lovers haunt his paintings. The merest profile is instantly recognisable, such is the frequency with which he came back to his closest subjects. By the time you’re done, you don’t need to go read the label to spot George Dyer.

And it is these portraits of his lovers which are the most interesting. Bacon was gay at a time when it was illegal to be so, and came from a family where his sexuality set him apart. His relationships were intense, even violent. Dyer, in particular, had a profound impact on Bacon, his sudden death at a time of professional success (a major exhibition in Paris) setting the course for the artist’s subsequent output and career. We see Bacon work through internal turmoil on canvas. Pain becomes art, as is so often the case.

Final Thoughts on Francis Bacon: Human Presence

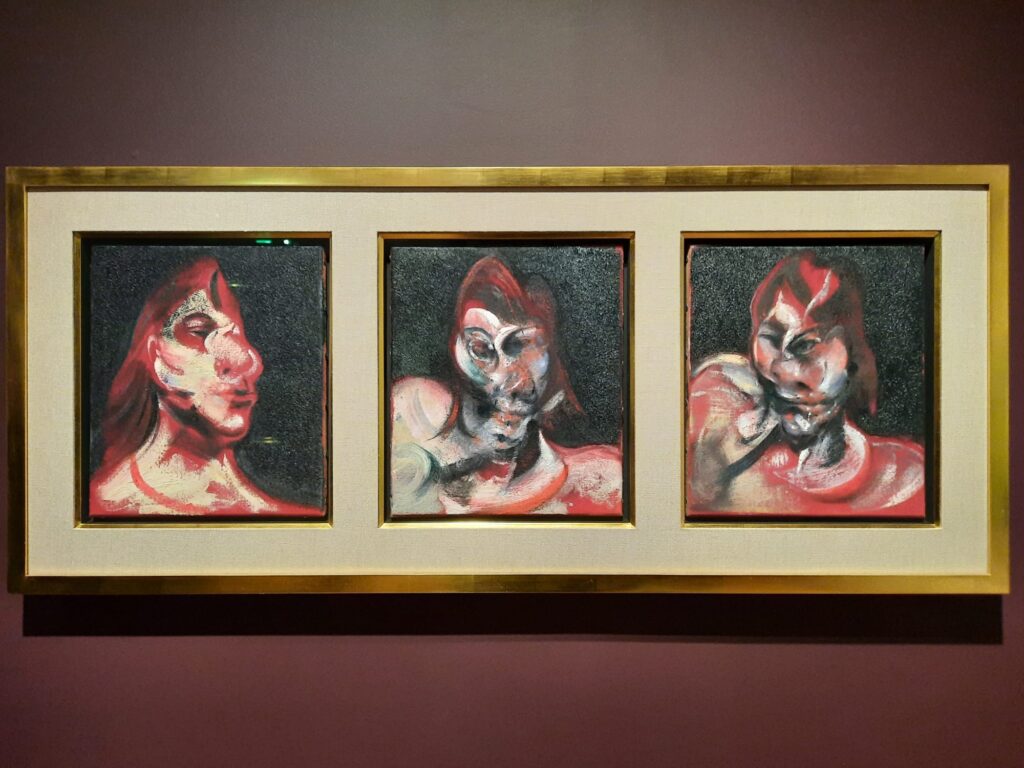

Curators, take note. What I would really like to see is a tightly focused exhibition, exploring one of the many avenues hinted at in Francis Bacon: Human Presence. For instance: portraits of lovers. Or triptychs. I think there’s something really interesting you could do looking at just the triptychs and the light they shed on Bacon’s oeuvre. Just the early portraits, or just the late ones. The characters he met and spent time with in Soho. There are a lot of possibilities.

Trying to cover the development of Bacon’s portraits from start to finish was always going to be a colossal task, and difficult to get right. And as I say, it’s not that I didn’t enjoy this exhibition. There are plenty of great works on view, including loans from abroad and from private collections. I liked some of the objects around the paintings, like reference images and photographs of the artist. I learned a lot, and gained a newfound appreciation for Bacon’s dialogue with art history and modern artists in particular. It’s just that there was really a lot to wade through to get to these insights.

So unless I make a late dash for it in January, that’s goodbye to the London winter exhibition season. And quite the season it’s been, with blockbusters (like this and this), new discoveries (like this and this), and journeys to far off places. We now await with interest what 2025 will have to offer.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Francis Bacon: Human Presence on until 19 January 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.