Czech Cubism, Permanent Exhibition of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague

In this permanent exhibition of Czech Cubism in a Cubist setting, we learn how Prague was perhaps the most important centre for this modern art movement outside Paris.

Permanent Exhibition of Czech Cubism

On a recent(ish) trip to Prague, I had the opportunity to visit some places I’ve never been before. This is what I love about return visits: as much as I love a long weekend, it’s never enough to truly get below the surface of a new place and get around all the sights that might interest you. What is even better, I had a local guide for part of this weekend in Prague, and thus uncovered some interesting places I may not have encountered alone.

This exhibition of Czech Cubism is firmly in that camp. It’s basically a self-contained museum of Czech Cubism, but is technically part of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague. Prague museums seem to absolutely love splitting their collection thematically between different buildings – the National Gallery has a number of sites as well. But there is a reason to have the permanent Cubist exhibition where it is: it is housed in a Cubist building. And it’s one we’ve seen before on this walk: The House at the Black Madonna, or Dům U Černé Matky Boží.

But why have an exhibition on Czech Cubism at all? And why are there Cubist buildings in Prague, for that matter? Let us transport ourselves back to the early 20th Century to answer that question. The Cubist movement was most active in Prague between around 1911 and 1914, although it was not called Cubism then but ‘New Art’. Prague at the time had a vibrant intellectual and avant-garde artistic scene. It was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, so well connected to cutting edge developments across Europe. Einstein lived in Prague at the time, as did Franz Kafka: both attended literary salons to debate new and interesting topics.

Cubism, Czech Style

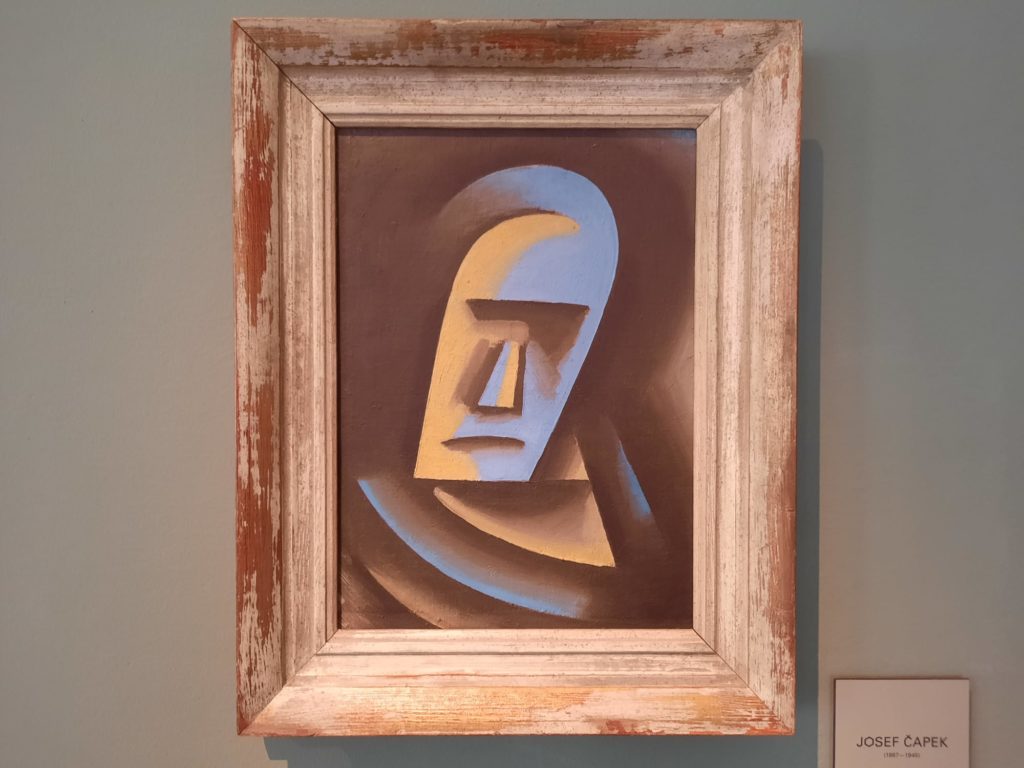

Cubism itself got its start a little earlier, of course, in Paris. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque began to turn out Cubist canvasses around 1907. Rejecting the idea that art should copy nature, Cubism instead exaggerated forms by emphasising geometric shapes, often showing the same object from different angles in order to represent its essence rather than one view of it.

Czech Cubism, interestingly, was not entirely abstracted from nature. It all comes back to crystals. Collecting crystals was apparently a common Czech hobby throughout the 20th Century. For artists looking to understand the fundamental truths of matter and perception, crystalline shapes were a perfect fusion of nature and order. Czech Cubism also spread far beyond the confines of what we might consider ‘fine art’, to applied art and architecture. The Group of Fine Artists (Skupina výtvarných umělců) was very influential in spreading Cubist ideas, and comprised painters, sculptors, architects, designers, illustrators, art historians, and art critics.

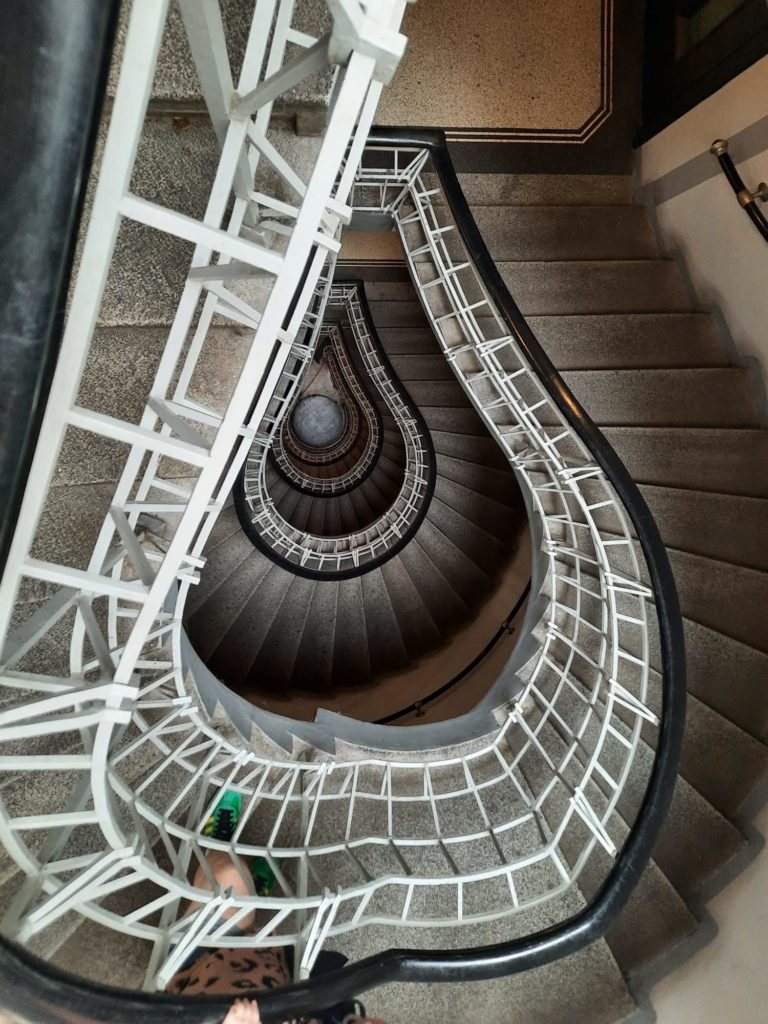

The Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague’s permanent exhibition attempts to demonstrate the full range of Czech Cubism’s possibilities. Let’s start with the building itself. Completed in 1912, it is named for the Baroque sculpture which adorns it, a remnant of an earlier building. The architect was Josef Gočár, and it was originally a department store. It uses a reinforced-concrete skeleton to maximise internal space. Today it has a restored café on the first floor, featuring Cubist furniture and chandeliers. Typical Cubist elements can also be seen in the geometric exterior decoration, dormer windows, wrought iron work and the internal staircase.

Everything You Could Need For a Cubist Home

Having entered the building, make your way up the stairs to start your tour from the top down. And a side note: the museum attendants may not speak English. If they come to speak with you (and if you don’t speak Czech), it’s likely they’re asking to see your ticket.

The exhibition gives a good sense of the breadth of Czech Cubism. There are artworks in the traditional sense: paintings and sculptures. As well as the House at the Black Madonna, there are architectural models of other famous Cubist buildings. There is furniture, ceramics, decorative objects, lighting and so on. Surviving Cubist fabrics are very few and far between, but the curators have used a bit of creativity to incorporate some. If you’re anything like me, you will be able to imagine living with some of the pieces. Others are most definitely in the avant-garde category. But most of it, with its angles and unusual shapes, is very striking indeed.

All in all, I really enjoyed the permanent exhibition of Czech Cubism. It is is a nice size to incorporate in a busy day in Prague. The first floor café (as opposed to the ground floor café) looks like a lovely spot to chat over a coffee. And it made tangible a sense of Prague as a progressive intellectual and artistic centre in the early 20th century. Definitely one to consider for lovers of art and history visiting the city.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.