The House Of Dreams Museum, London

Stephen Wright’s House of Dreams Museum is a remarkably intimate experience which puts into sharp focus the objects which surround us and the traces we leave behind.

The House of Dreams Museum

Despite being a voracious consumer of art and culture, I don’t often speak to artists about their art. I guess this blog, for me, is a way to engage with all the wonderful things I see, while staying at a bit of a remove. I can take it all in, go away and think about it, and formulate my thoughts before I share them. So being greeted at the House of Dreams Museum by Michael Vaughan, husband of artist Stephen Wright, was just the first way in which this intriguing place fosters intimacy and connection.

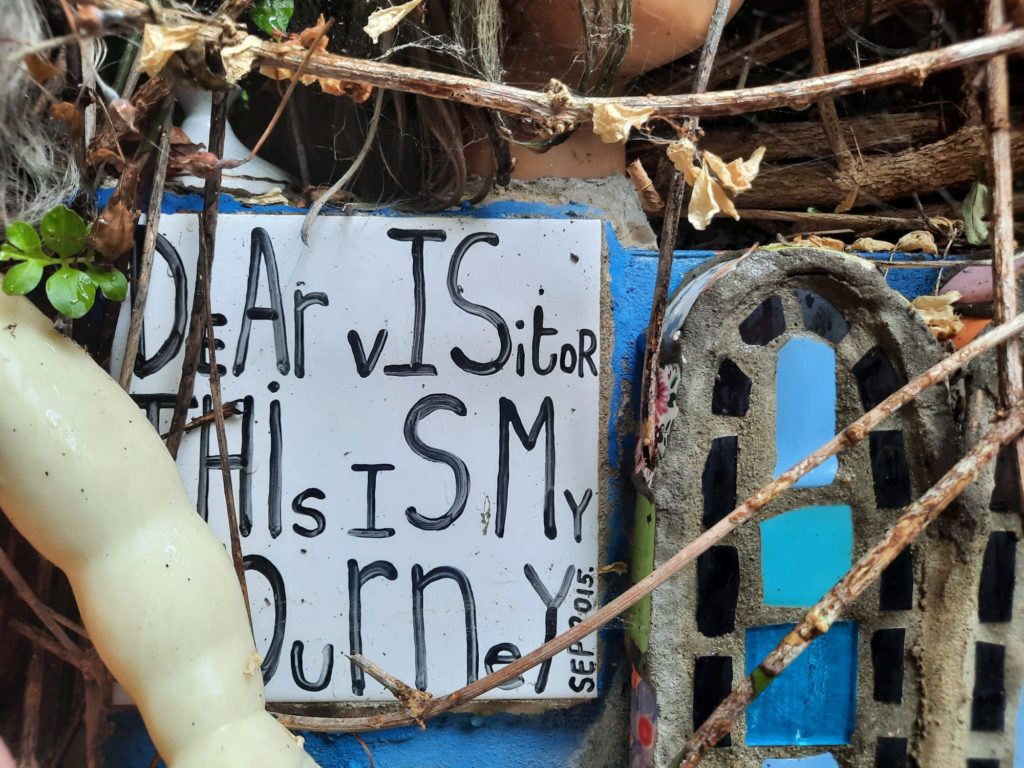

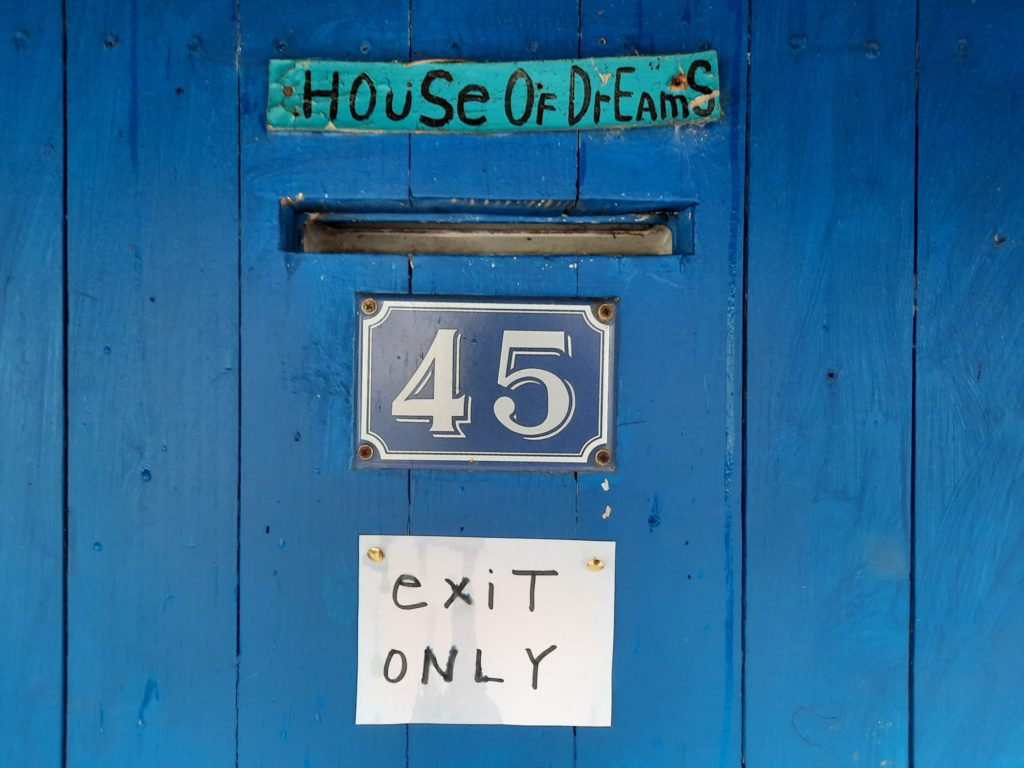

The House of Dreams Museum grew organically, from a small mosaic in 1998 into several rooms and the garden of a semi-detached house in East Dulwich. That first mosaic was a collaborative effort by Wright and his partner Donald Jones. They continued to work on it, spreading colour and pattern over the floor and walls. Wright took a break from the project after a difficult period in which he lost both Jones and his parents within the space of 18 months. When he came back to it a year or two later, it became something much more personal, helping him to process the loss and love of these important people in his life.

I had been wanting to visit the House of Dreams Museum for a while. I’m always on the lookout for new places to visit, even better when they are not only interesting but close to my South East London home. And so on a rainy Saturday (the first rainy open day they’d had for a while, it seems), I headed to East Dulwich. Monthly open days see about 100 visitors pass through the House of Dreams Museum. And as well as a welcome briefing by Michael, I had the chance to speak to Stephen about his work.

A Place of Memory

As well as being able to speak to the people who live with this extraordinary project, I have watched the various videos about it here. I recommend you do the same: they’re a remarkable resource. Wright mentions a few times in the videos that he’s not great at communicating with words. I find he is actually very considered and thoughtful about the language he uses.

Let’s start with the sort of art that this is. At first glance, the House of Dreams Museum has the markers of outsider art – it’s free, colourful and uninhibited. You know the Salterton Arts Review has a great interest in outsider art, so that is undoubtedly a big part of the draw for me. We could have another discussion about terminology here, but let’s instead focus on comments Wright himself makes in this video. Outsider art is art by artists without formal training. Wright spent seven years studying art (and worked previously in textile design, fashion and stationary design). But he freely acknowledges that he works “in the spirit of outsider art”.

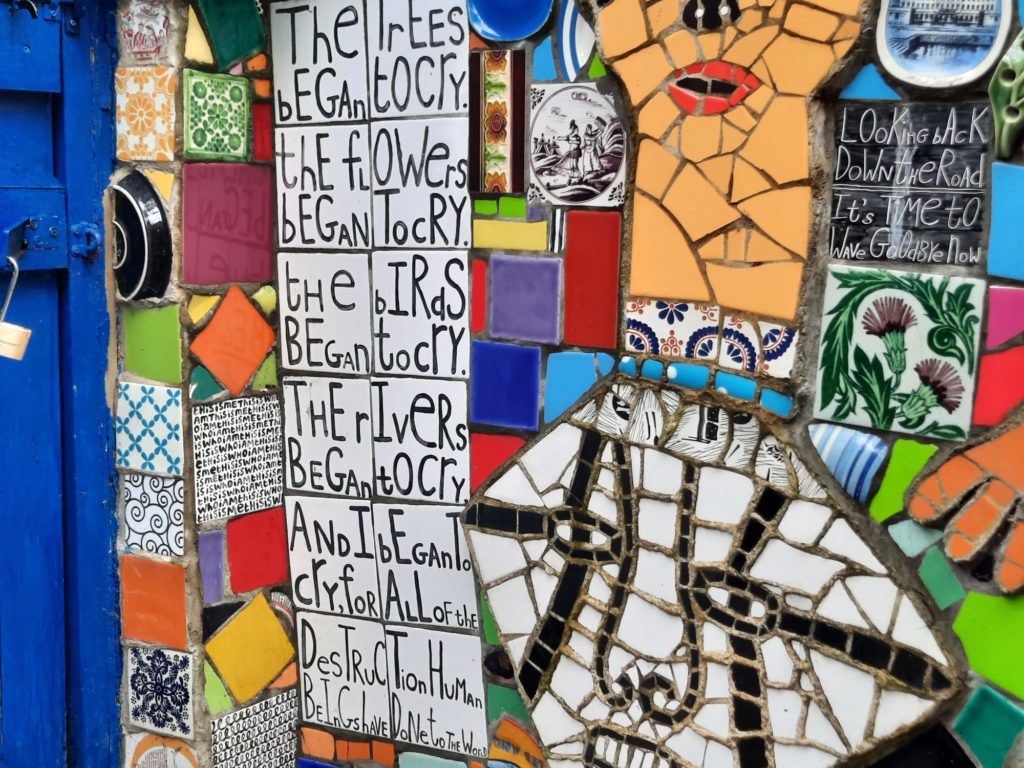

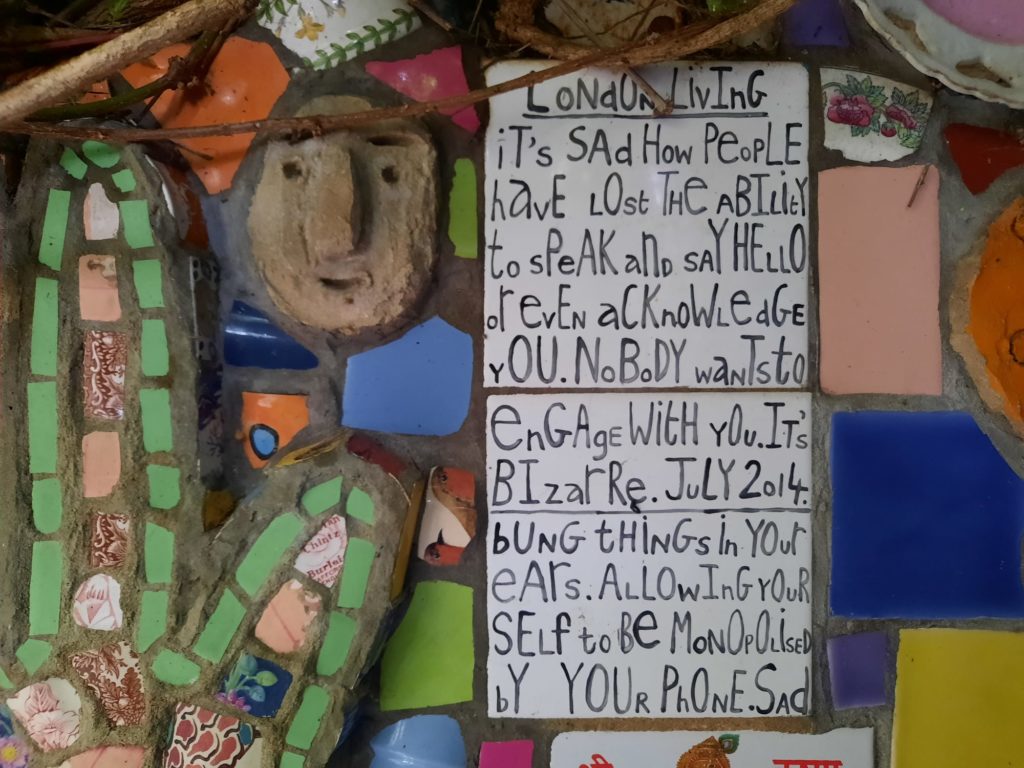

Like much outsider art, the beauty of the House of Dreams Museum is the way it sees things others miss. You can’t take photos inside, but you get a feel for the aesthetic from my photos of the garden. Every surface is covered in objects: false teeth, cosmetics, hair rollers, dolls. A lot of dolls. This is another area where Wright’s use of language is very telling (and deliberate). In various sources I’ve seen, he talks about disabled dolls. Dolls whose eyes don’t work, who have skin conditions. Wright finds them discarded at markets or other places, and takes them in. Loves them. As someone who also feels an obligation to objects nobody else may value, I find this very touching.

The other thing that proliferates in the House of Dreams Museum is writing. Wright has created a lot of work based on diary entries. And often the topics come back to his love for his parents and Donald. And their loss. The overall effect, however, is joyful rather than sad. The types of objects Wright collects and uses remember their owners’ presence. They are the traces we leave behind. And so this very personal project is accessible to all of us. We can spot objects that spark memories, that draw us in, that remind us of someone. We read the texts and understand some of the objects more deeply. Wright’s art is his language. Language is his art. The two most definitely intertwine.

An Intimate Experience

Another thing which feels intimate about the House of Dreams Museum is our very presence here. It was included last year on a list of top house museums by the Financial Times. But unlike a lot of entries on the list, this isn’t a posthumous curation of objects and artworks. This is a lived-in house, on a residential street. And it wasn’t always open to the public like this. It seems that, while the project started collaboratively with Wright’s then-partner Donald Jones, it is the support of husband Michael Vaughan which has shepherded it to this place where we can step inside and share in it.

And what a special thing that is. Like I said at the outset, it’s not my usual comfort zone to have the art or the artist look back at me while I look back at them. But when the art feels like an extension of the artist to this extent, discussing it feels not only safe, but natural. And part of the beauty of the House of Dreams Museum is that everyone will take something different from it.

If this post has inspired you and you live within reach of East Dulwich, take a look at upcoming open days here. If you’re further afield, watch these videos as the next best thing. Perhaps you’ll enjoy it from a place of memory and nostalgia. Maybe you’ll be inspired by the way Wright has said yes to all those impulses, rather than denying parts of himself. Whatever your motivation and whatever you take away from it, I feel confident it will be a rich and rewarding experience.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

Oh dear, I’ve been reading your blog for sometime. And enjoy it.

For me, this seems like a surrealist nightmare! I’d be making an excuse to get out the door! But I appreciate some people might enjoy it.

Thank you first of all for the feedback! It wasn’t my comfort zone to be in conversation with an artist about their art in their home, especially with art that is so personal and aesthetically not everyone’s cup of tea. But I tend to like art that is really passionate and tells a story, so definitely enjoyable from my point of view.