The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 – Barbican, London

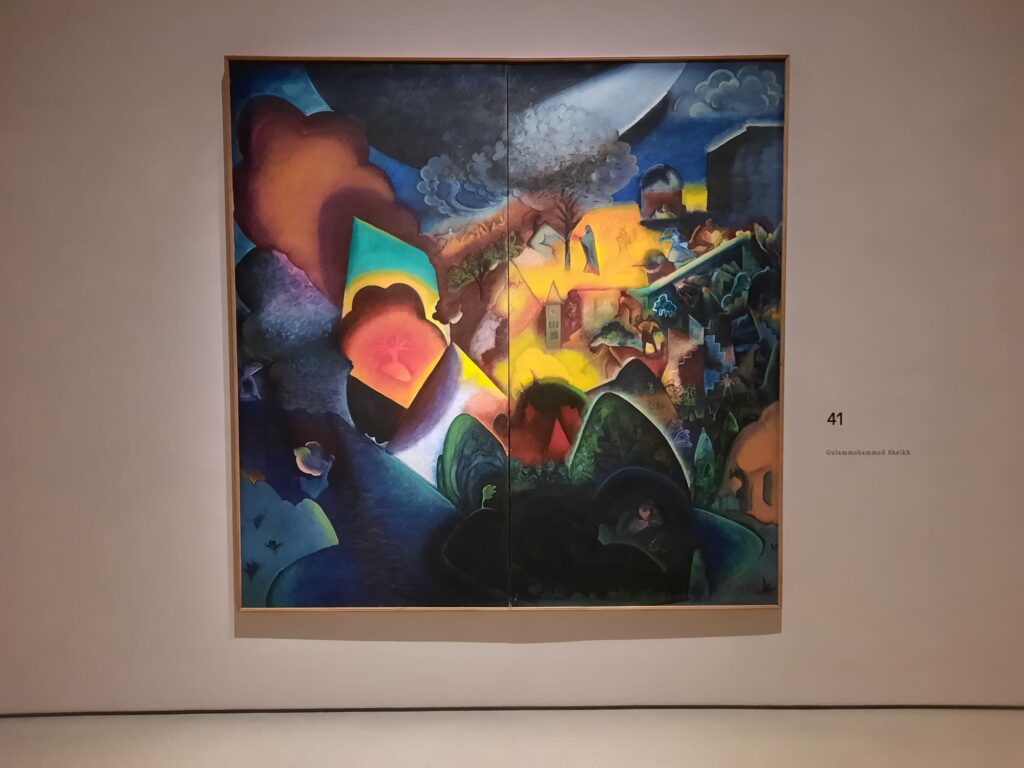

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 mines a rich but little-explored seam in Indian Art in which disillusionment, urbanisation and social change became inspiration for artists across this vast and varied country.

Introduction: Why These Dates?

The Barbican’s current exhibition, The Imaginary Institution of India, surveys Indian art between 1975 and 1998. A good stretch of time: not too long ago, not so recent as to not be able to understand its impacts on the present. But why those dates? What is their significance in Indian history and art?

We’ll start with the history. 1975 is easy. That is the year that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency which lasted 21 months. It’s one of those things that’s easy to see coming, in hindsight. Gandhi had done a pretty good job consolidating power, chipping away at rights, and installing supporters in key political roles. But not everyone was happy about it, or about a perceived lack of progress on issues that mattered to them, and there was increasing unrest in the form of protests, demonstrations and strikes. Gandhi, through president Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, declared an emergency on 24 June 1975, citing internal and external threats.

Over the course of the next 21 months, the Emergency had an immense impact on life in India. Over 100,000 political opponents were jailed: people like protesters, strike leaders, trade unionists, dissenting Congress leaders. Elections were postponed, and laws rewritten with few checks and balances. Tax breaks and price controls ensured some measure of popularity for the government, while forced sterilisation left a deep scar on the bodies and minds of millions. An ambition to abolish poverty saw rapid changes to housing, particularly in urban areas. By the time the Emergency ended in March 1977 following elections that swept Gandhi and her party out of office, an indelible mark had been left on India.

And 1998? This is arguably the date when India took a seat as a world power by that predictable means: nuclear weapons. India detonated five nuclear weapons in the Thar Desert in Rajasthan, becoming the sixth country to establish a successful nuclear weapons programme. There’s little more than a footnote in the Barbican gallery guide timeline but again this was an important moment in Indian history. We’re not going to look at the legacy of sanctions, global power shift, or impacts on local populations, though. The exhibition ends here as another watershed moment, India having taken a new place on the world stage outside of its postcolonial context.

The Imaginary Institution of India: Why This Exhibition?

OK, we now know why the period 1975-1998 was important in Indian history. But what does that have to do with an exhibition at the Barbican? I’m being a little facetious here, of course. It’s no secret that artists (and other creatives) respond to their environment, including politics, social change, their urban or rural location, and so on and so forth. So it would be astonishing not to see the consequences of the period in question in art. This is art as documentation: responses and perspectives on events created more or less in real time.

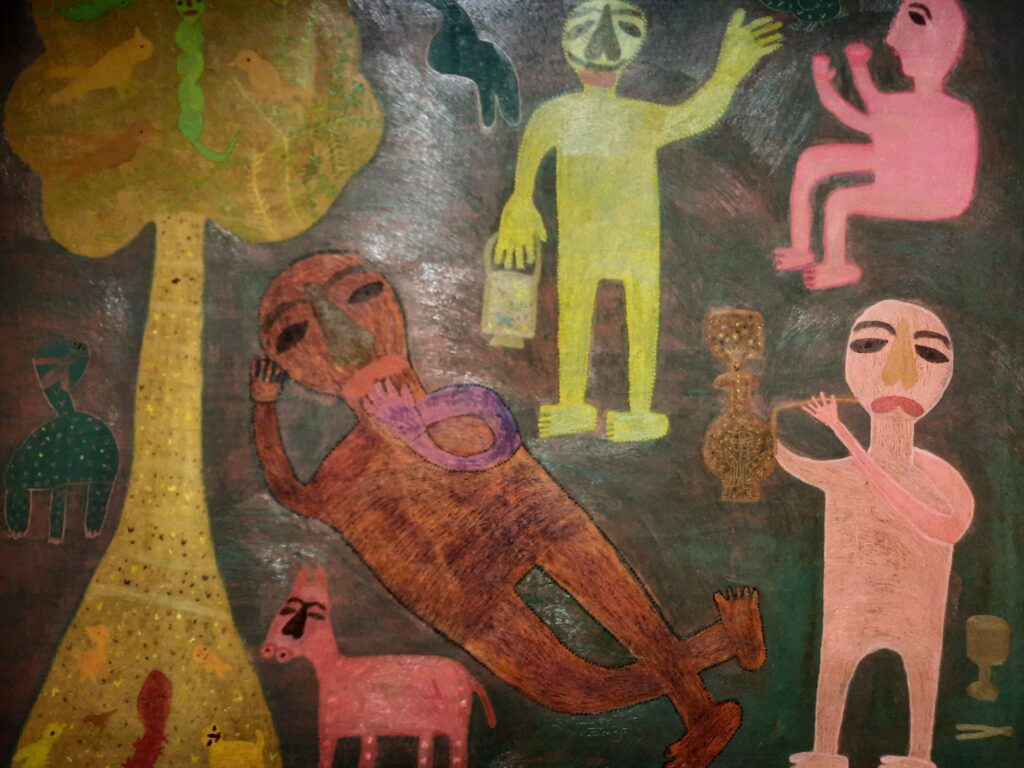

It is also a fresh perspective on India and its art. In fact, this exhibition is a world first. There’s never before been a survey on this scale of Indian art from this period, with this focus. And it’s important. When we think of Indian art we’re typically thinking of a few things. Classical art, perhaps: miniature paintings, religious art, fine objects, the Mughal period, or artists responding to new colonial clients. Or the continuing interest in vernacular art, ‘Outsider’ artists and traditional skills. At a stretch we might be thinking about art relating to the fight for independence and the Partition, although in my experience that tends to surface more in history, literature and theatre. So this exhibition is a broadening of perspectives.

It’s also important that the exhibition is in London. It’s a partnership with the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi. This means a lot of great loans, supplemented by loans from other institutions and private collections. A lot of art, basically, that isn’t normally available to us in the UK. I wrote recently about the dearth of Sikh stories in UK museums in particular, but Indian stories as a whole are probably under-represented given the size of the diaspora. Particularly, again, more recent stories. Occasionally modern Indian artists like Francis Newton Souza are seen in group exhibitions. But this exhibition, in London, a major world city with profound historic and contemporary connections to India, feels significant. And a treat for eager consumers of new subjects in art and cultural history, like myself.

Curating the Imaginary Institution of India

The exhibition title, by the way, comes from a 2010 book by Sudipta Kaviraj, the idea of an imaginary institution speaking to India’s heterogeneity, multiple identities and internal contradictions. And the big exhibition space at the Barbican is necessary to try to give any sense of this plethora of viewpoints.

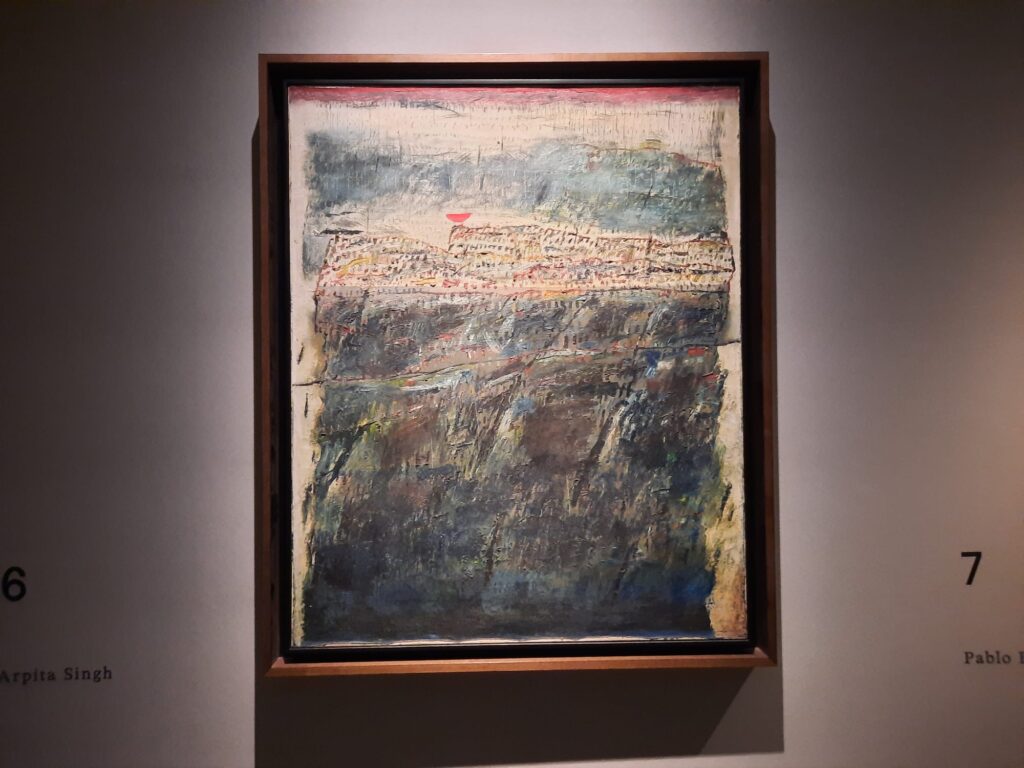

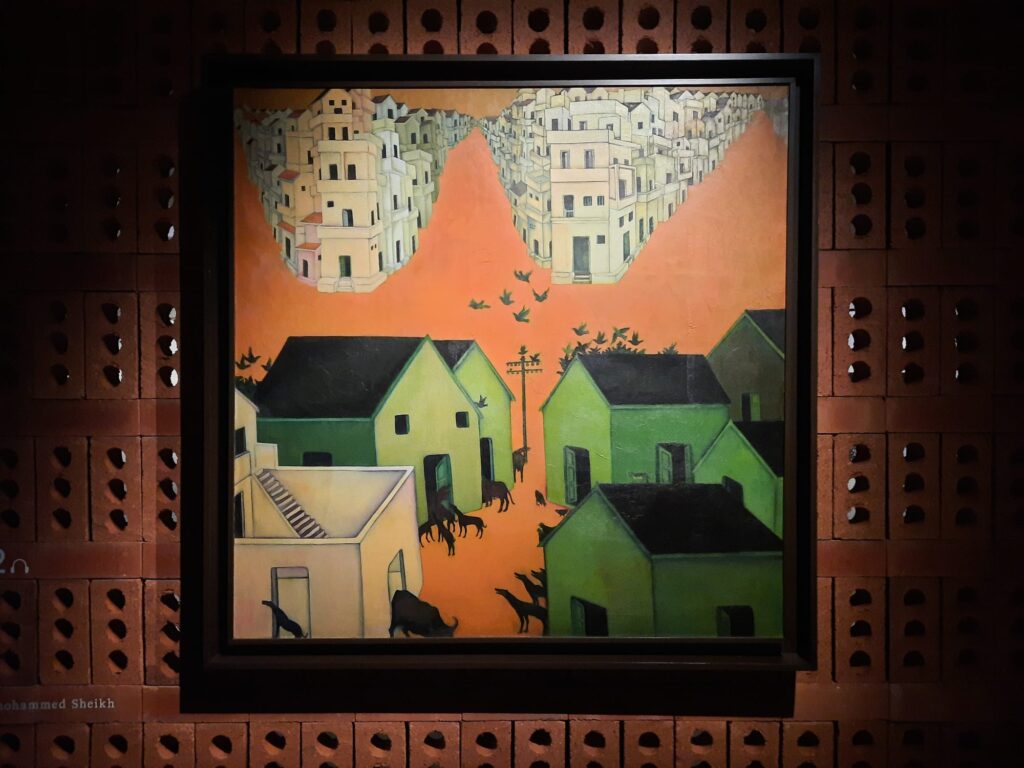

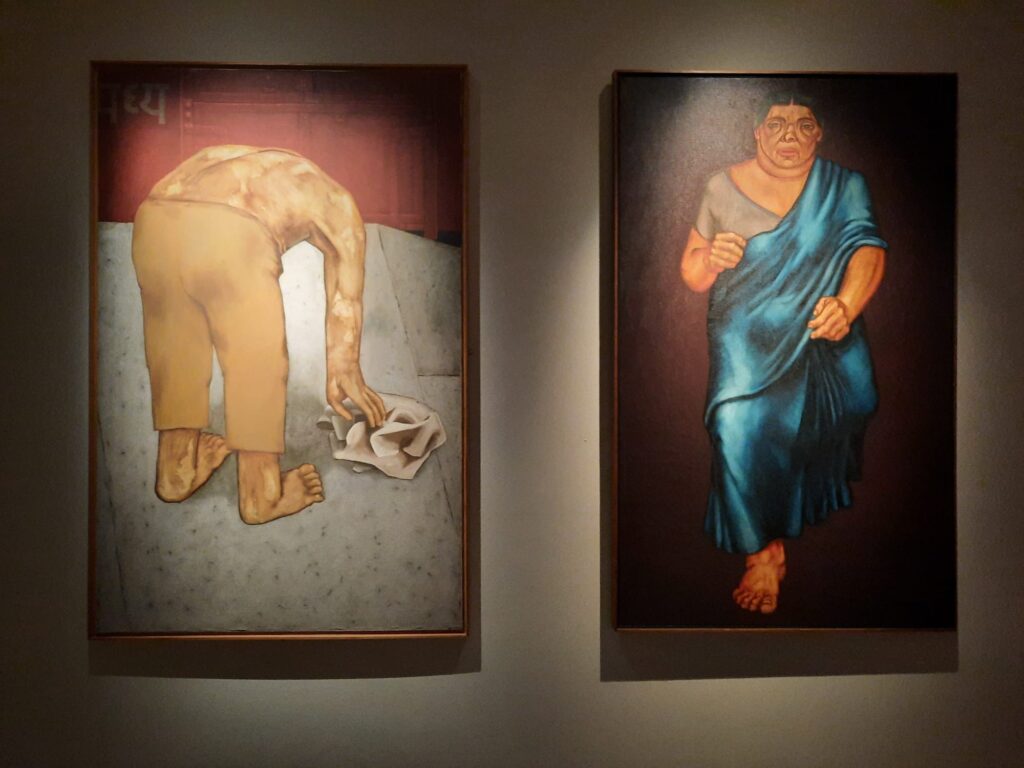

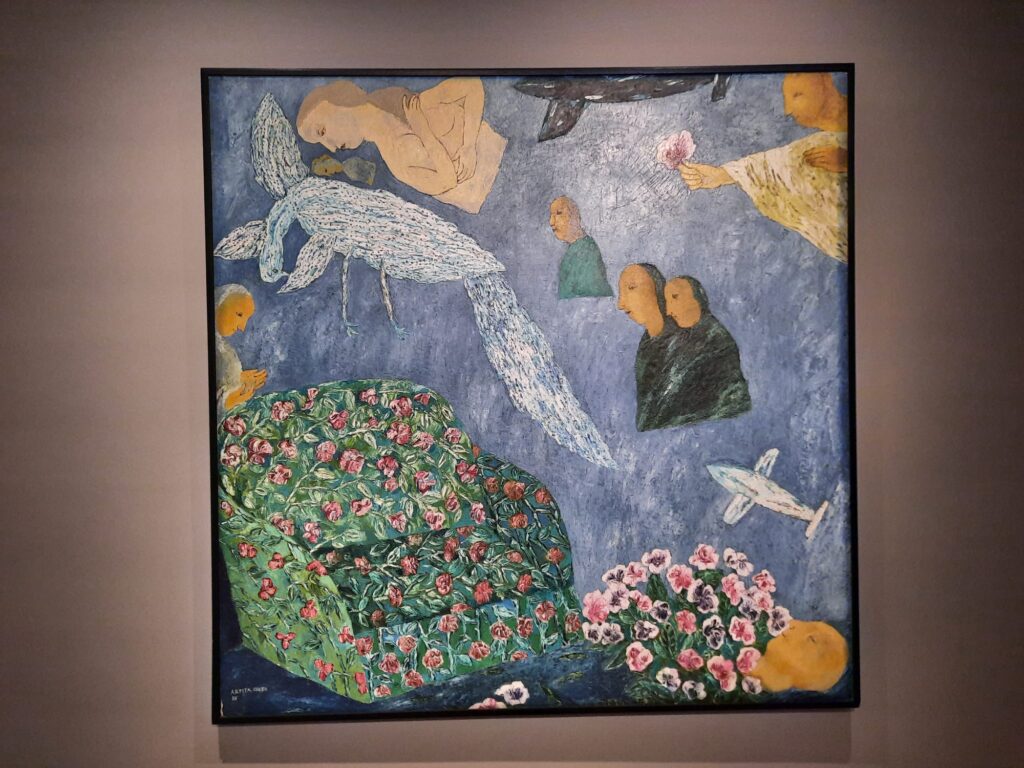

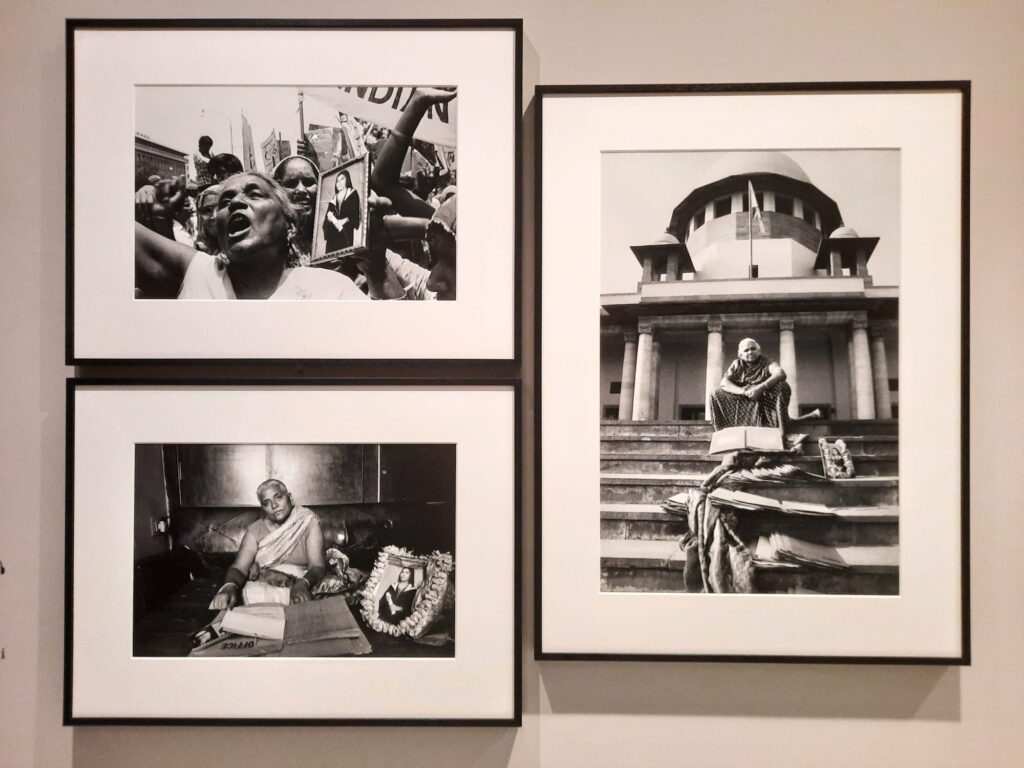

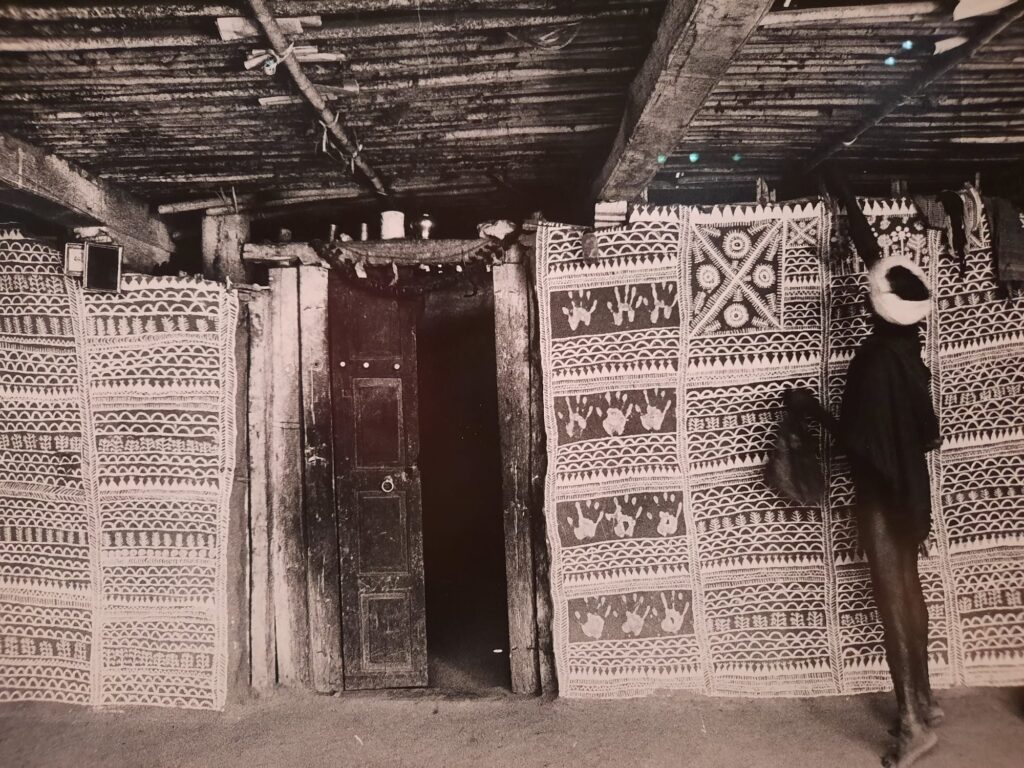

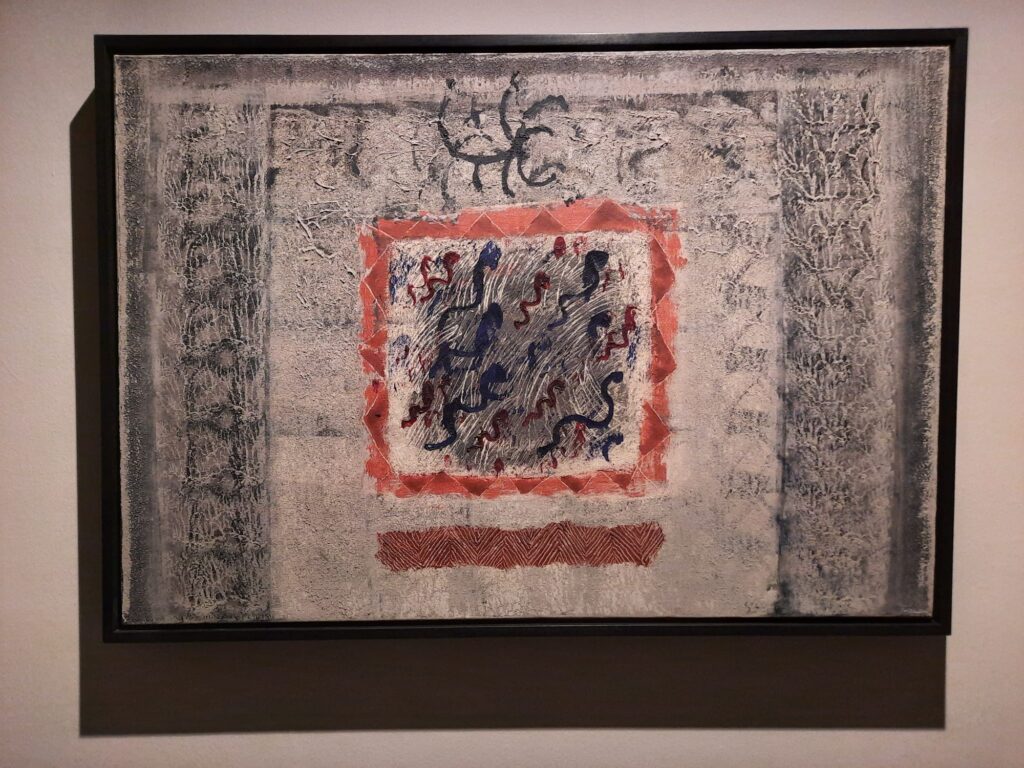

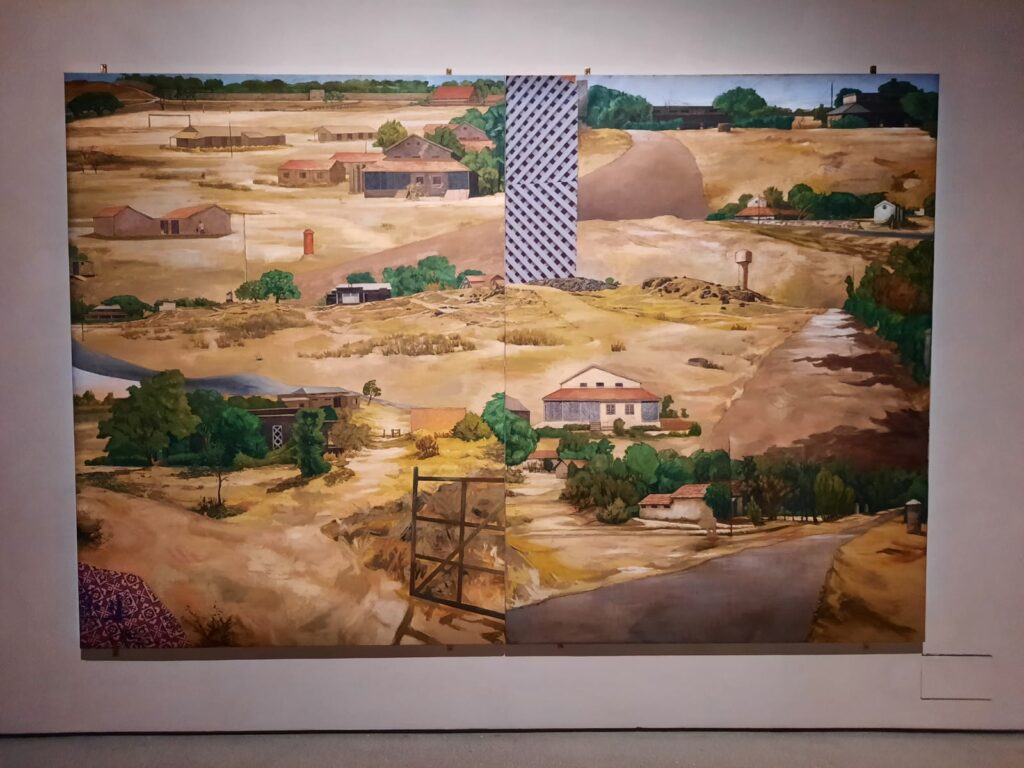

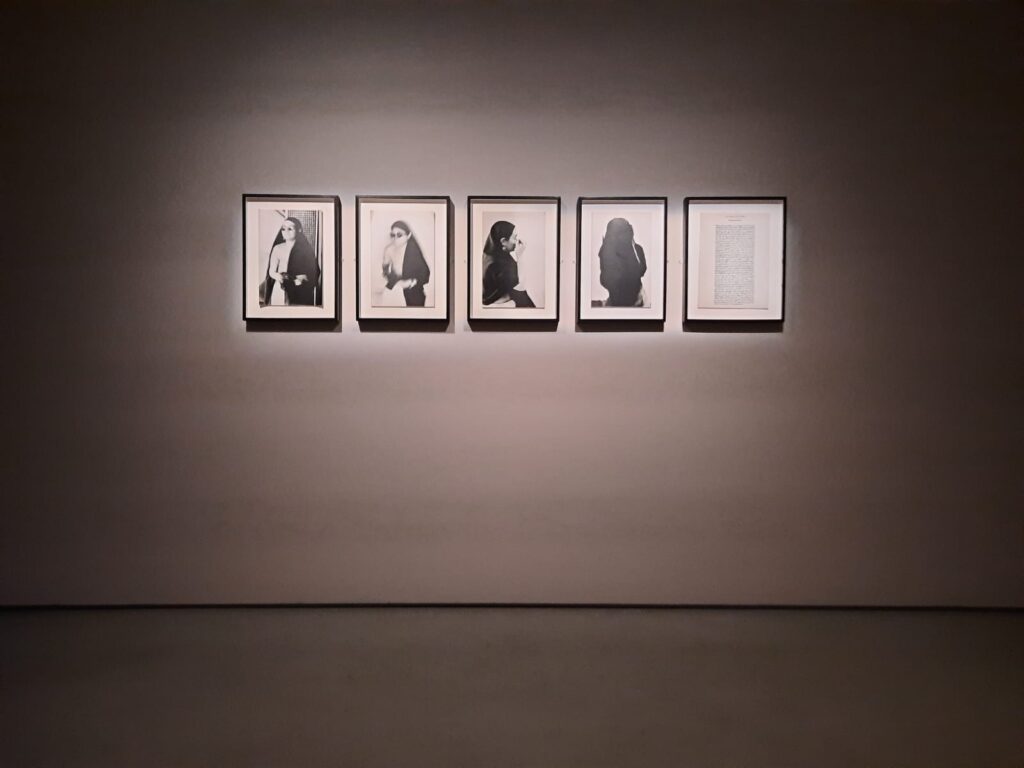

The exhibition starts, as (nearly) always, in the upstairs mezzanine galleries. It’s broken into four themes. We start by looking at physical changes to urban and rural spaces: the impacts of urbanisation, a changing economy, and movements affecting class/caste consciousness. Next up is a section on gender, feminism and sexuality. The third theme looks at how contemporary artists responded to traditional or indigenous/Adivasi art and different ways of life between city and countryside. Before finally we get into the politics of the period, tensions, unrest, violence and resistance.

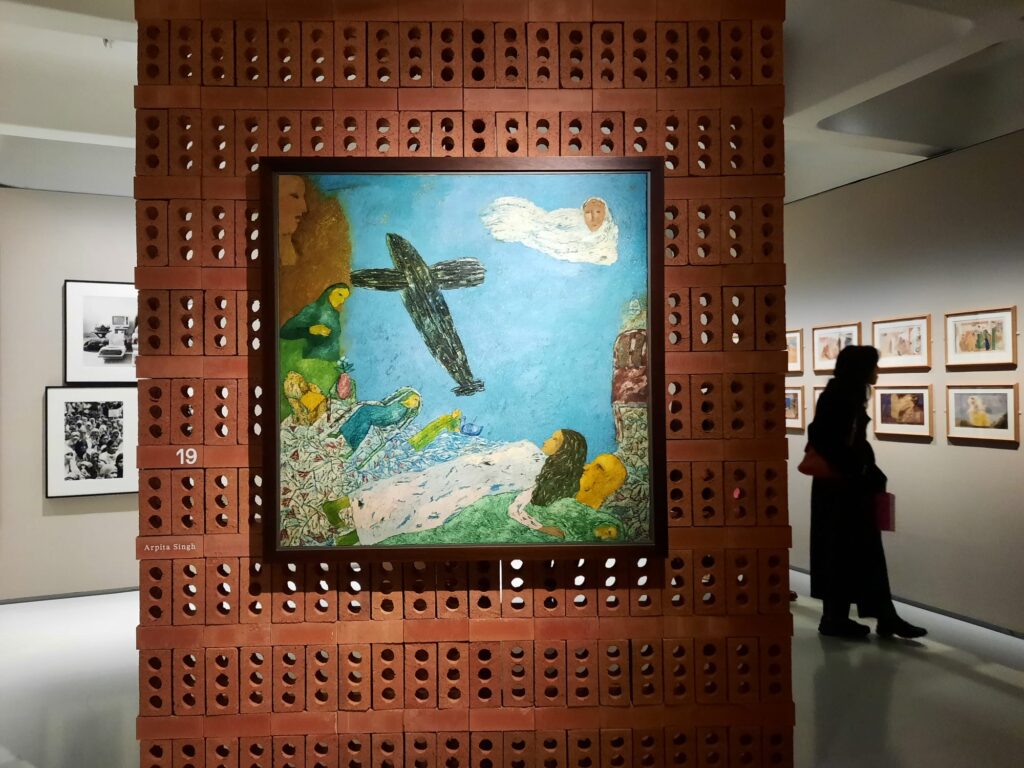

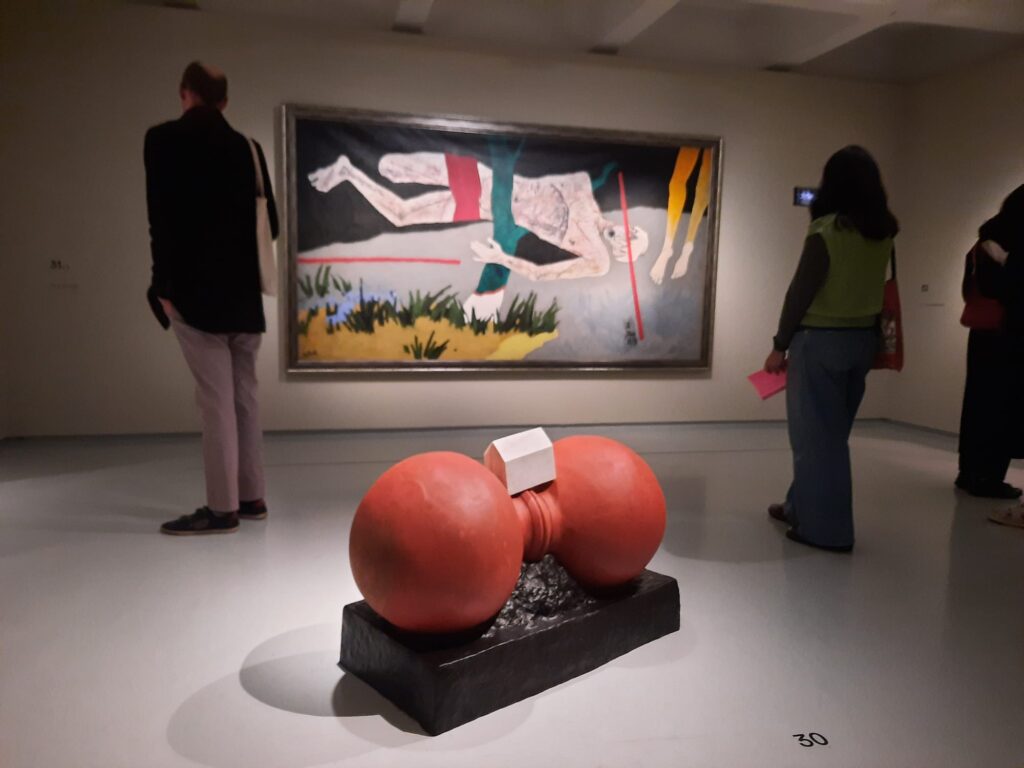

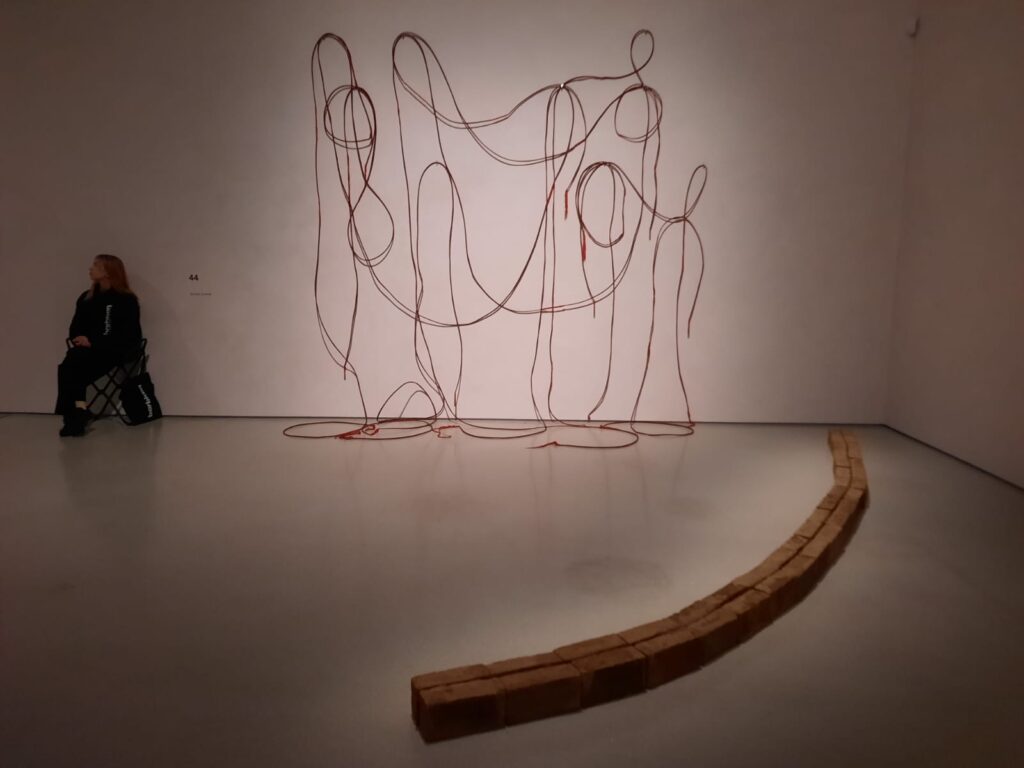

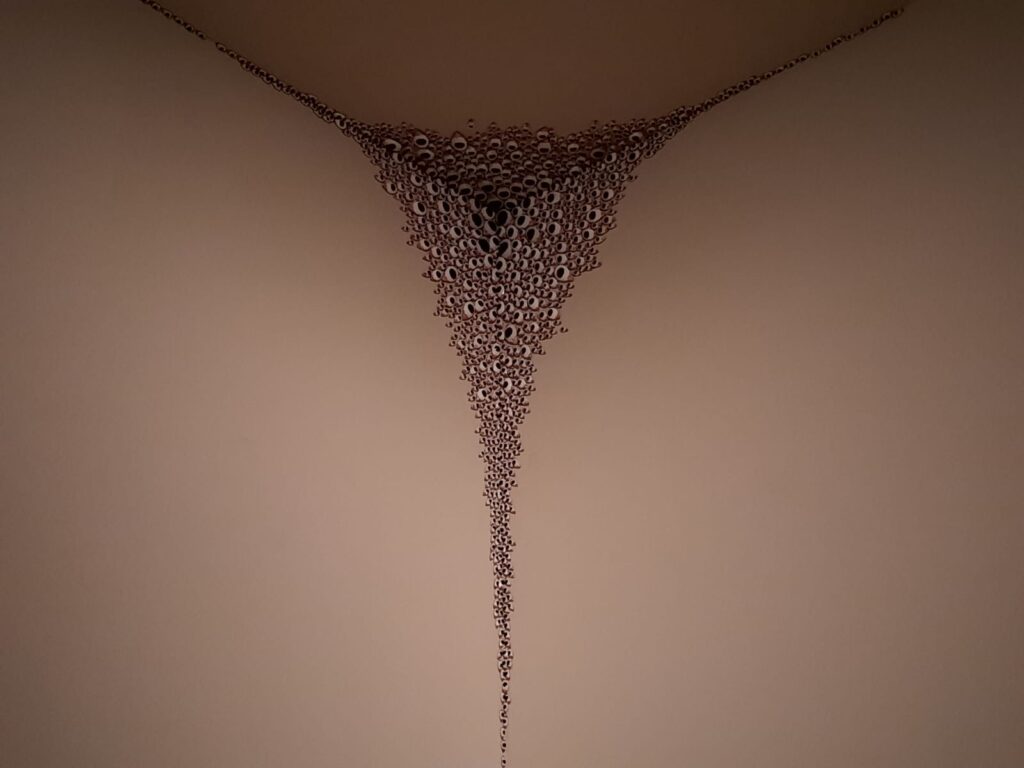

The presentation of the artworks is satisfying. The spotlighting is dramatic and sombre. It would be terrible for trying to read texts and labels, but luckily these are mostly all in an accompanying booklet. Temporary partitions are made of brick and wood, evoking the changing (particularly urban) environment. And the way the thematic groupings progress, it feels apt that we move from smaller paintings, sculptures and photography upstairs to larger installations and sculptures downstairs. Like coming to an apex, knowing that something explosive is around the corner.

A Few Highlights

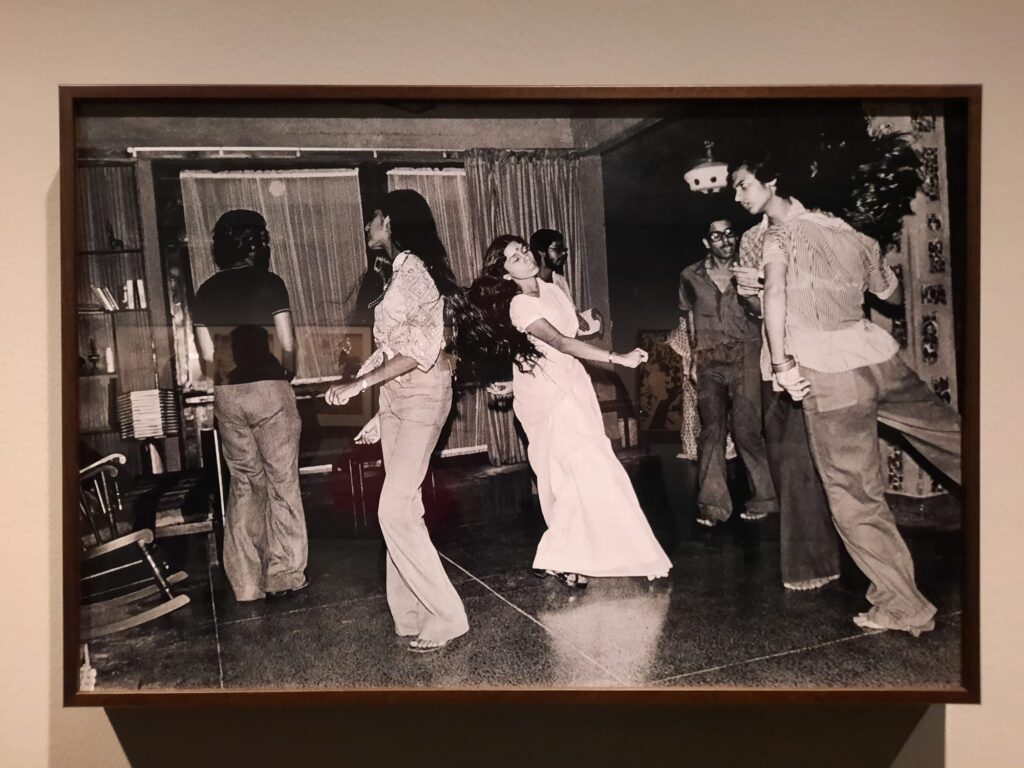

There is much to enjoy in this exhibition, even if the subject matter is not always easy. One perspective I particularly appreciated was the trajectory of artists over time. By this I mean there are 30 artists represented in the exhibition, and about 150 artworks. Sometimes you will see a few artworks by the same artist together. A series of photographs by Sunil Gupta (Exiles, 1987), for instance, of gay men amongst New Delhi’s landmarks and cruising sites. Coincidentally, we saw some of the same series here years ago as part of Masculinities. But I digress. My point is that I liked when an artist cropped up in the exhibition, then again later but with a clearly shifting outlook on life and art.

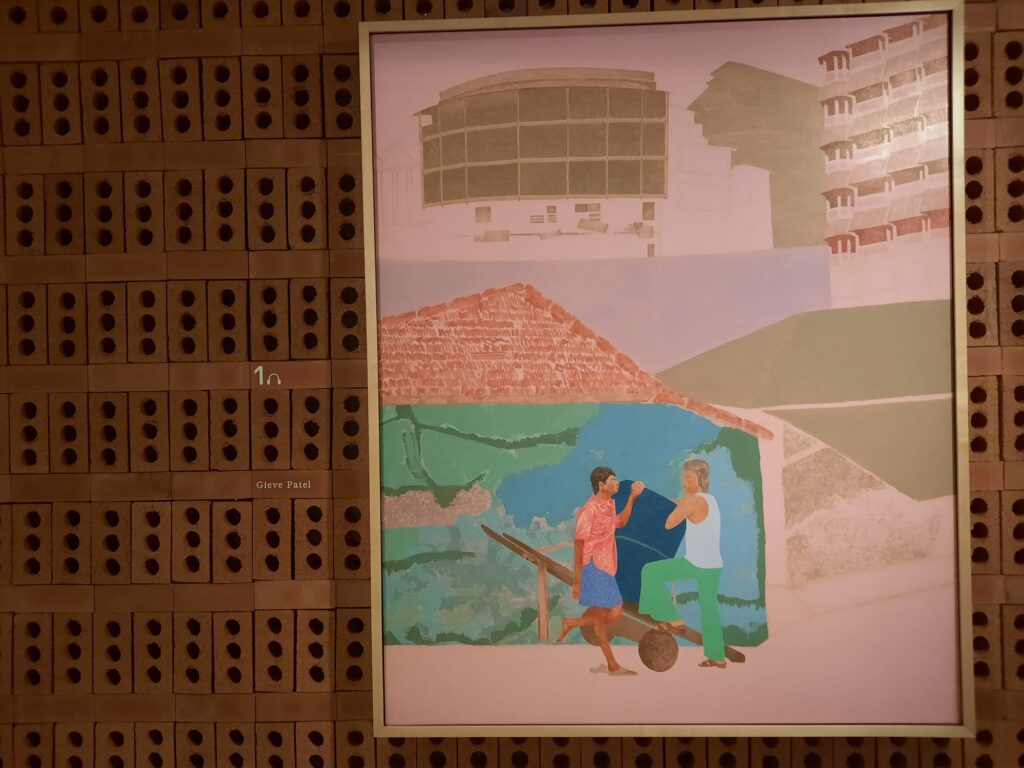

Take Gieve Patel, for instance. One of Patel’s works, Two Men with Hand Cart (1979), opens the show. Under a pink sky, the two men look relaxed despite the changing city around them. A little bit later we encounter Off Lamington Road (1982-86). This is a busy street scene featuring happy figures as well as destitute ones. The crowd includes adults and children begging, while a naked woman lies bleeding in the street. As a practicing doctor in Mumbai as well as an artist, perhaps we can surmise Patel had contact with those for whom the promises of independence and Indira Gandhi’s populist slogan ‘Abolish Poverty!’ were well and truly unfulfilled by this point. By the time we encounter Patel in the 1990s the title, Battered Body in a Landscape (1993) almost says it all.

I enjoyed the often vibrant, frequently challenging works on the mezzanine level. Moving downstairs, the increased scale of some of the sculptures and installations was also pleasing. N. N. Rimzon’s The Tools (1993) is very striking when seen from upstairs and up close. A central figure stands in meditation, surrounded by broken and rusted iron tools. It seems to reference the displacement and forced change of globalisation, which was making itself felt in rural communities at this time. One of my favourite works was nearby: Nilima Sheikh’s Shamiana (1996). Consisting of painted scrolls (or kanats, ‘side screens’) forming a tent, it draws on Sheikh’s background painting backdrops for a feminist theatre troupe and also mythological and literary traditions. Its scenes of journeys taken by women feels powerful and calming as the artworks beyond its embrace reflect a sense of violence and danger.

A New Perspective on Indian Art

Coming back to The Imaginary Institution of India’s central purpose, what did it contribute to my perspective on Indian art? Quite a lot, in a nutshell. First and foremost, it opened up a new set of artists and art movements I was not familiar with. Even when I’ve visited India, I’ve tended to be interested in history and monuments. My knowledge of modern and contemporary Indian art outside the big names like De Souza is limited. And not just getting to know new artists but seeing how their work developed over their careers is a rare joy.

Also a joy is the sheer breadth of works on view. There is the range of media I alluded to earlier. Photography, painting, lost wax sculptures, installations, video art, drawings, collage, stacks of cow dung: the list is almost endless. But there’s also the huge variety of subjects and topics. Historic events like the Bhopal disaster of 1984. Homosexuality, women’s rights, dowry-related violence, child marriage. Caste politics, including the Dalit movement. Rapid urbanisation, political disillusionment, increasing violence. The status of artists and indigenous Indian (or Adivasi) forms of art.

Each of these media or topics could be a small exhibition (or sometimes a large one) in its own right. That they all hang together and are not completely overwhelming points to very good curation. Including the right selection of works. I feel I learned a lot during my time here: about art, history and society. Many of the works stirred emotional responses, too. What more could you ask of an exhibition, really?

Final Thoughts on The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998

And that, in a nutshell, is my perspective on this exhibition. Well-curated, a great opportunity to see works rarely seen in the UK, and plugging a sizeable art-historical gap. An almost incredible breadth of artworks and subjects, yet still comprehensible in terms of the broad themes and key points.

So we come back to this idea of an imaginary institution of India. It speaks to the creation of a country which was India, in a colonial context. To the need to unite disparate peoples in order to fight for independence. And then attempt to govern those people and meet their many needs. When things started to unravel under Indira Gandhi’s leadership, her answer was to rule by force, imprisoning opponents, removing civil and democratic rights, and even controlling population growth through extreme measures. Over two decades later another key moment in Indian history united (for the most part) the country, marking India’s entry onto the world stage in a new way.

What a privilege to be able to go to the Barbican, a relatively short distance away, and learn about all this on a Saturday morning. I could hope that we will see more exhibitions of this calibre on different facets of Indian art. But it’s more sensible for me to urge you to see this one while it’s here. And should I ever make it to New Delhi, I will be pleased to see many of these works back in their original setting at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. Artists will always respond to what’s happening around them. And it’s frequently the case that, the more ‘interesting’ the times, the more interesting the art. What we learn from it may be idiosyncratic, sometimes biased, frequently partial. But it’s also the emotive lens to balance the factual (and also biased) nature of history books.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4.5/5

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 on until 5 January 2024

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.