Exploring Hong Kong’s Heritage I: Ping Shan Heritage Trail

The Ping Shan Heritage Trail in Hong Kong’s New Territories is a great way to spend half a day. Get out of the city and step back in time amongst ancestral and study halls, temples and shrines.

Hong Kong: Getting Under the Skin of a City

You may remember a while back I posted some reviews from HKPAX, the inaugural Hong Kong Performing Arts Expo. Although leisure was not the aim of my visit to Hong Kong, the Salterton Arts Review is nothing if not good at juggling responsibilities to squeeze in a bit of culture on any excursion. And so, with the time I did have available, I thought about what to see and do.

This was not my first visit to Hong Kong. In fact I’ve been a few times, going back as far as 2007. Any first visit to this small territory is likely to be urban. Seeing the skyscrapers of Hong Kong Island, perhaps from the Peak or Kowloon. Taking the outdoor escalators up to the Mid Levels. Catching the Star Ferry across the harbour. Over the years I’ve added more experiences. The big Buddha on Lantau Island. Exploring the islands for hiking or swimming. The Temple of 10,000 Buddhas. Even Hong Kong Disneyland.

But on this trip, I got to thinking about what makes Hong Kong unique. The thing about our globalised world is that, to a large extent, a city is a city. Sure, Hong Kong is different than London, in terms of climate, geography and sights and sounds. And yet we move through one urban environment much like another. So for this visit I decided to focus on unique aspects of Hong Kong’s history.

That history, as you can imagine, goes back a long way. Hong Kong has always been of relative interest due to its location and natural harbour. In Prehistoric times, it was a site of salt production. During the Chinese Imperial period, it was a fairly distant territory. The population grew largely due to refugees from Mongol invasions, and various clans moving down from Guangdong. There wasn’t particularly good agricultural land, so people relied on salt, fishing and the pearl industry. The British could see potential for international trade here though, and occupied Hong Kong Island during the Anglo-Chinese War in 1841, forcing China to cede the territory in 1842. Further territory was leased in 1898 for 99 years, expiring in 1997 when Hong Kong became a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. How’s that for history in a nutshell?

The Ping Shan Heritage Trail

So where does the Ping Shan Heritage Trail fit into all this? Well, the Ping Shan Heritage Trail was the first of its kind in Hong Kong, opening in 1993. In terms of my whirlwind historical overview (which, granted, excluded a lot), it is part of that clan phase of Hong Kong’s history. The Tang clan moved here from Guangdong (formerly anglicised as Canton) in the 12th century. Tang Yuen-Ching and his son Tang Chung-Kwong were the first of the Ping Shan Tang lineage.

Setting up a heritage trail here was the result of the combined efforts of several organisations: the Antiquities Advisory Board, Antiquities and Monuments Office, Architectural Services Department, Hong Kong Jockey Club, and the Lord Wilson Heritage Trust. And, of course, the Tang Clan themselves, who still live in Ping Shan and use several of the buildings for community activities.

The trail is 1.6KM in length, and easily reached from public transport. It starts at a Heritage Centre in a former police station, and ends back near the closest MTR station (Hong Kong’s subway). Between those two points, a basic map guides you around several sights. Not all are open to the public, but most post opening hours to the heritage trail website. Payment is not required to visit any of the buildings. For visitors, it’s a chance to see traditional Chinese buildings like Ancestral Halls, Study Halls, temples and walled villages. For residents, the status of a heritage trail affords protection: many of the buildings have been listed before or after the trail opened in 1993.

If you wish to follow the trail yourself, you can find more information here. Click on the map to bring up the building listings. Please note the map is representative rather than accurate: having Google Maps to hand helped me to find my way on a couple of occasions. You can also pick up a hard copy of the trail information by starting your visit at the Heritage Centre as I did. And please note there are other Heritage Trails available in Hong Kong: this is just the one I found the most interesting and accessible for my half day outing!

Let’s Get Started: Ping Shan Tang Clan Gallery cum Heritage Trail Visitors Centre

The Ping Shan Heritage Trail starts in a nice hilltop location with views of the surrounding area. It’s surprisingly lush, and a far cry from the high-rise skyline of Hong Kong Island! It’s housed in the Old Ping Shan Police Station, one of the last remaining colonial police stations in the New Territories, completed in 1900. The police vacated in 2001, and the visitor centre opened in 2007.

I’m glad this feature has been added to the trail, because it’s a very good addition. For visitors unfamiliar with Ping Shan, the Tang Clan or Hong Kong’s history, it gives a good overview using archival sources. There are also loans of objects from local families, including furniture, clothing, household and agricultural objects, and ritual objects. Community members tell their own stories in filmed interviews. It’s simple, but does the job.

I particularly liked the old photographs of the area, showing what life was like here. Originally, the Tang Clan established “Three Wais (walled villages) and Six Tsuens (villages)”. Today it’s more like one suburban area or village, so the archival images help to set the scene. Learning about the rituals and rhythms of life in Ping Shan also helps to bring some of the later buildings to life. I liked that the local community seem to have been so involved in the creation of this heritage centre.

Hung Shing Temple

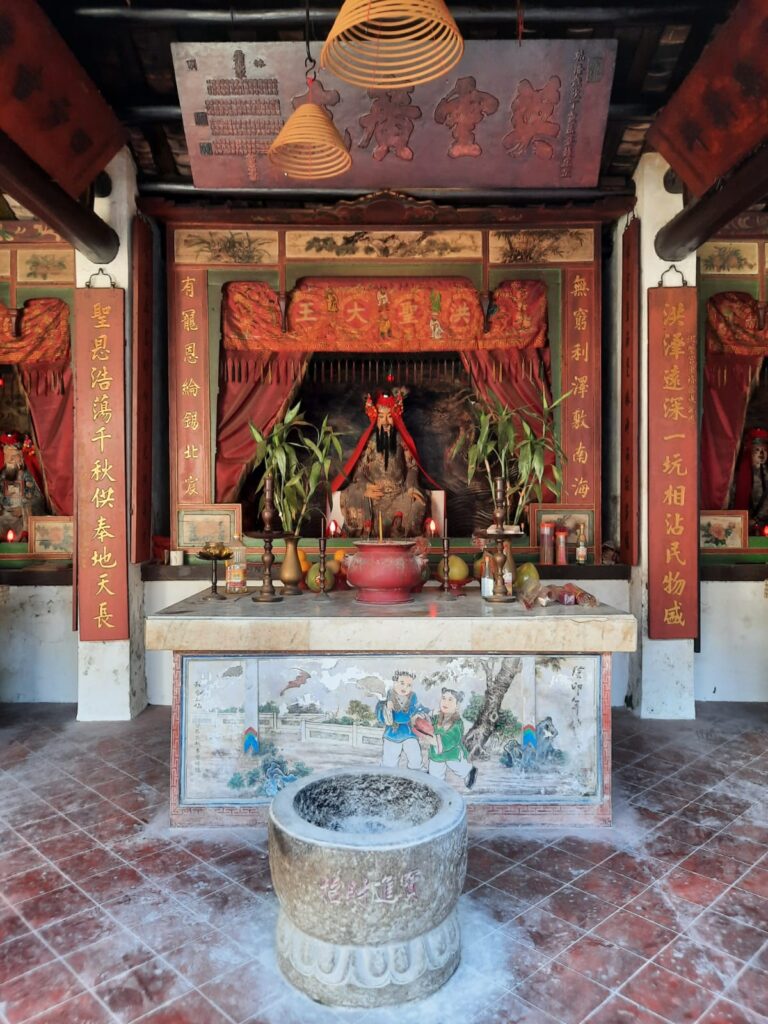

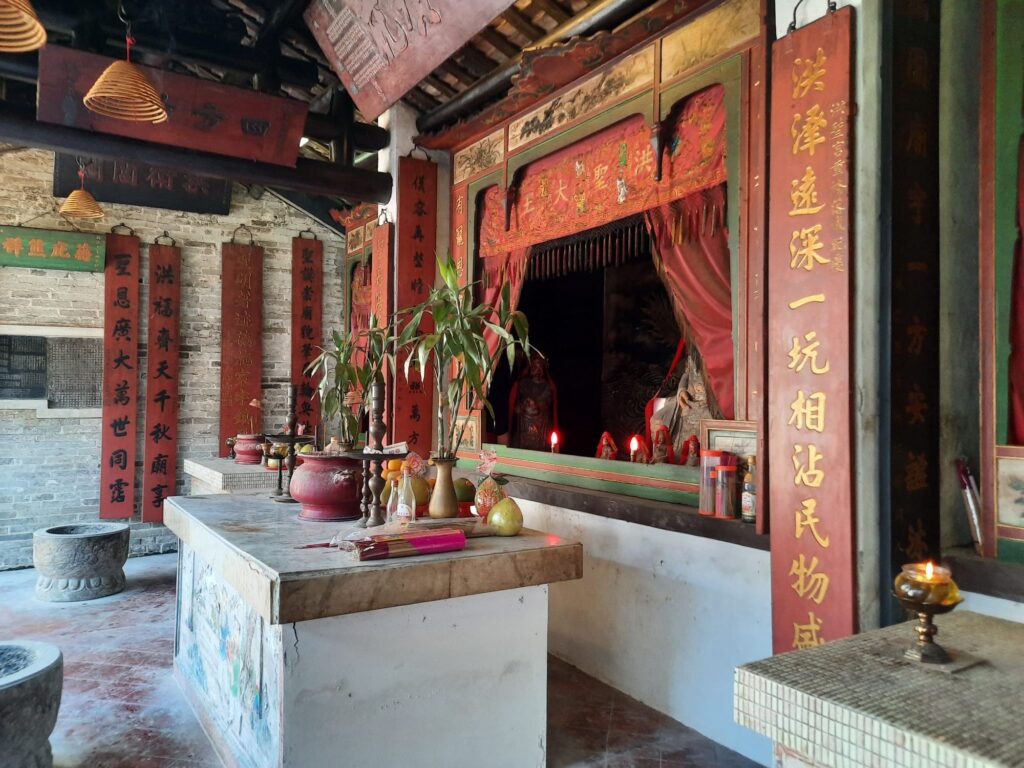

Our next stop, Hung Shing Temple, is located in one of Ping Shan’s six villages, Hang Mei Tsuen. Hung Shing, or Hung Shing Tai Wong (洪聖大王) is a deity in Chinese folk religion. In life he is said to have been an official in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). He most likely derives from Zhurong, the fire deity and god of the southern seas. In this blended historic and mythical version he is portrayed as a righteous and virtuous government official who, after his death, continued to protect the people, most notably from tempests. Temples in his name are particularly common in the Guangdong region.

A board inside this temple dates it to 1767 during the Qing Dynasty. It was rebuilt in 1866 and substantially renovated in 1963. It is a simple structure, consisting of two halls and an open courtyard. The open courtyard is an unusual feature, as most temples in Hong Kong have replaced this open space with a roof forming an incense tower. Hung Shing Temple is relatively light and airy as a result, and is a well-preserved example. Stepping inside, I saw residents stopping off to offer prayers, and smelled the fragrance of the incense coils common to Hong Kong’s temples.

Hung Shing Temple sits on a little village square which is a useful, shaded spot to sit and figure out your route through the remaining sights on the trail.

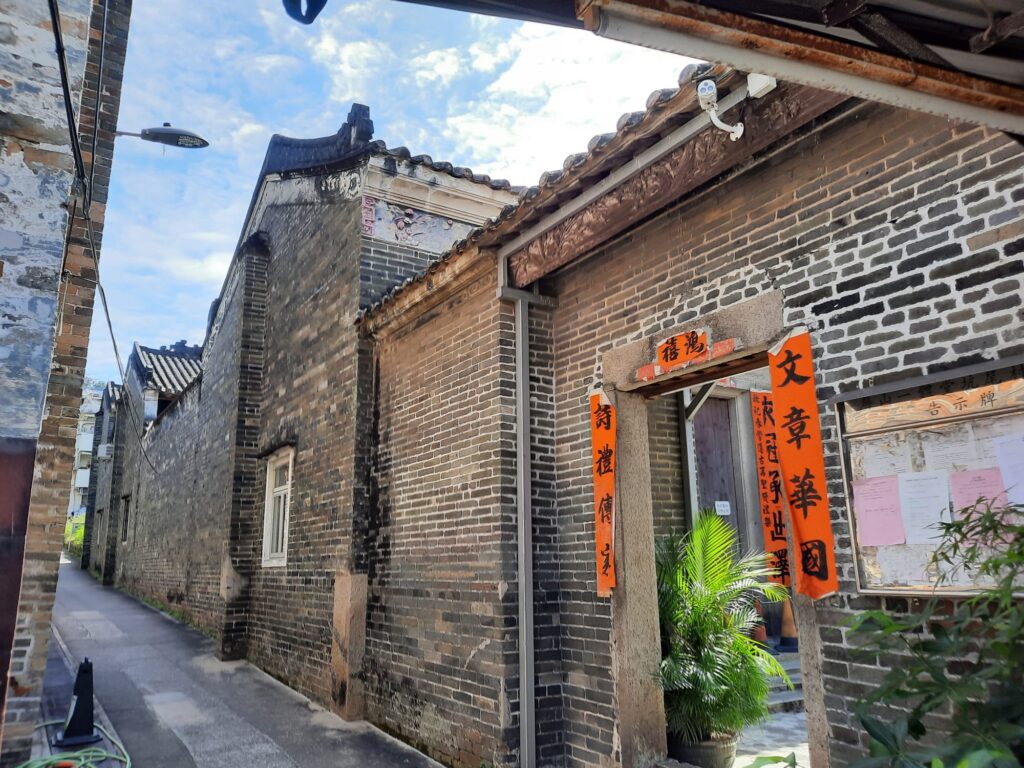

Entrance Hall of Shut Hing Study Hall

The first image above is of a shrine to (I believe) the Earth God, on the way to our next stop. There are a few of these around Ping Shan, including one which is an official stop on the trail, where I will explain a bit more. The next image just goes to show that, even with clear signage, things aren’t always easy to find. Someone pointed me in the right direction to Shut Hing Study Hall, there was this sign as well, but I still overshot and ended up at the other end of the village. No matter, it was a short walk back and I found it in the end.

Let’s start with what exactly a Study Hall is, then, before we learn about this one in particular. Study Halls go back to the Chinese Imperial period and their very serious exams. This method of selecting civil servants based on merit rather than rank started as early as the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE), and lasted until 1905. The examinations ensured a shared culture and ultimately a unified empire through testing candidates on language and literature.

A position in the government could mean prestige, wealth and power for one’s relatives as well as oneself, so was serious business. Clans thus set up study halls to prepare their young men to sit the exams. Traditionally the halls consisted of two parts: an Entrance Hall and a Study Hall. The Tang Clan built this example in 1874, but demolished the Study Hall component in 1977 as it was in disrepair. The Entrance Hall is thus all that remains.

Out of all the stops on the Ping Shan Heritage Trail, this is a very interesting one. Interesting firstly because the Entrance Hall is not on a street but is at the centre of a block of buildings. It’s actually part of them: the interior is now residential. It’s curious seeing this traditional architecture juxtaposed with people’s cleaning supplies and drying laundry. Well worth locating though for its roof ridge decorations, murals, and carved details.

Ching Shu Hin

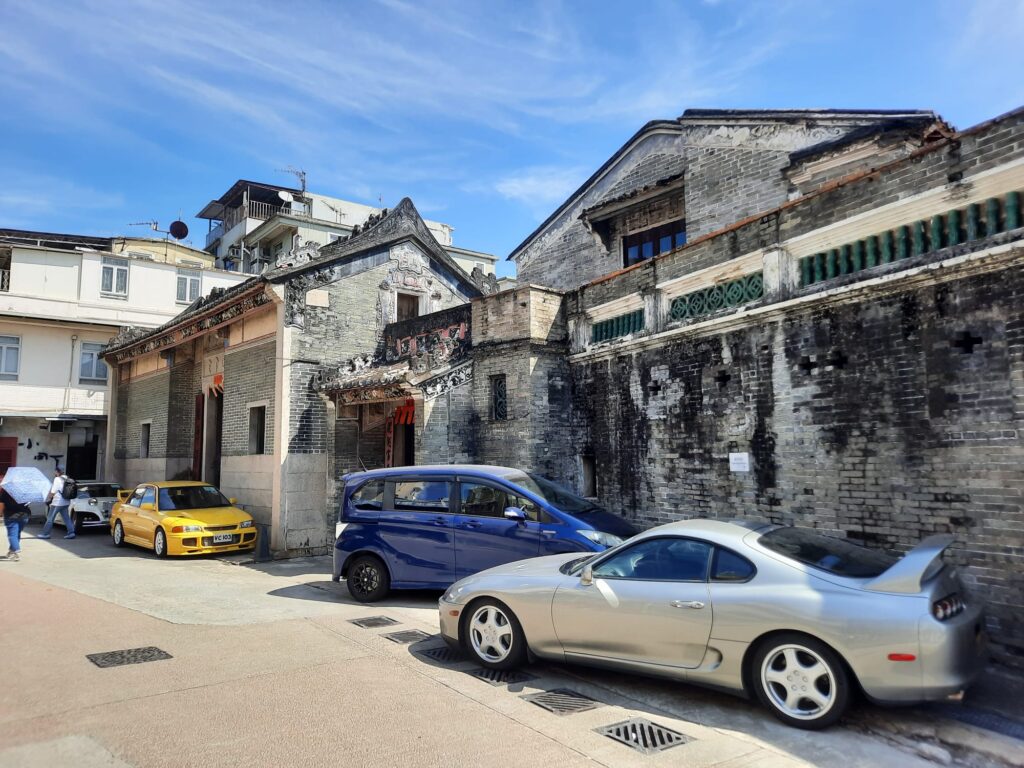

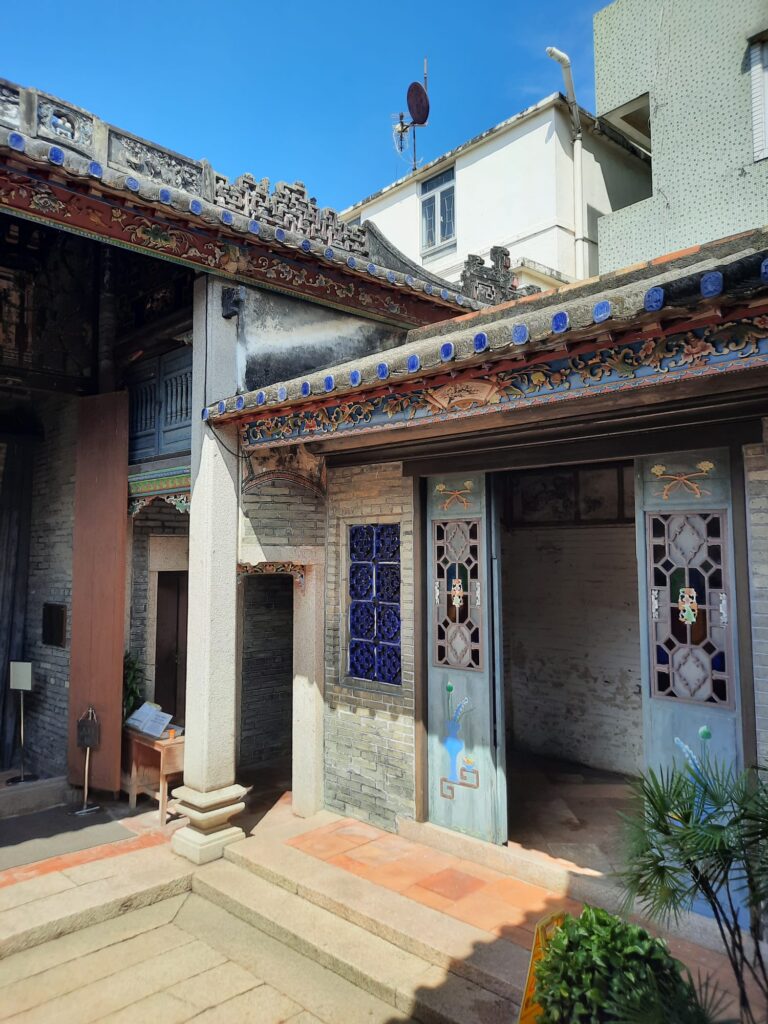

Just before we visit another Study Hall, we have what I thought was one of the most atmospheric stops on the trail. Ching Shu Hin is a guesthouse adjoining the upcoming Kun Ting Study Hall. Prominent scholars and visitors would stay here. The name came later and refers to one of the rooms within.

Linked to the Study Hall by a first storey footbridge, Ching Shu Hin is an L-shaped building. It has rich decoration for its illustrious guests. This takes the form of murals, mouldings, carved panels and brackets, and patterned grilles. I had the space to myself when I visited, and enjoyed wandering around and examining the decorations. I wouldn’t mind staying a guesthouse like that myself!

Kun Ting Study Hall

And now we have our second Study Hall of the Heritage Trail, Kun Ting. This time it’s intact rather than just the Entrance Hall we saw before. It dates to 1870, and actually combined the functions of a Study Hall and ancestral worship. The ancestral altar within has an attractive design showing the skill of the craftsmen who built it.

When the British occupied the New Territories back in 1899, they turned this Study Hall into a police station for a time. It later continued as an educational facility for the community, even after the end of the Imperial examinations. It was a school, in fact, until shortly after WWII. Despite the opulence of the adjoining lodgings, this is a relative simple Study Hall consisting of a two-hall building with a single courtyard.

Tang Ancestral Hall

We now come to two side-by-side ancestral halls. The first is the Tang Ancestral Hall, the main site of ancestral worship for the Tang Clan in Ping Shan. Tang ancestor Tang Fung-Shun reputedly built the Ancestral Hall here some 700 years ago. The Clan still use it regularly for worship, festivals and ceremonies, and community meetings. It has been a listed monument since 2001.

Benefitting from a major refurbishment in the 1990s, this is one of the finest examples of an Ancestral Hall in Hong Kong. It has a three-hall structure with two internal courtyards. The raised red pathway in the first courtyard suggests that all those study halls paid off and at least one resident held a high ranking government position. It has drum platforms with granite and sandstone columns supporting the roof. The fine wooden carvings feature auspicious Chinese symbols, and the ridges and roof have ceramic dragon-fish and lions. The display at the back is of ancestral tablets. These are physical tablets symbolising ancestors and giving them a spiritual home for veneration.

Finally, please note the stone tablets in the final image. I could be completely off base, but I wondered if they were something I had read about on the page for another Hong Kong heritage trail. The Lung Yeuk Tau Heritage Trail notes the presence of stone tablets to ward off evil spirits, placed at unfavourable locations (eg. where accidents have occured). If anyone can read Traditional Chinese and wants to correct me, please do so in the comments section below!

Yu Kiu Ancestral Hall

I haven’t found anything online or in the Heritage Trail materials to tell me why there are two Ancestral Halls side by side. But such is the case. This is the second of the two, Yu Kiu Ancestral Hall. It’s an early 16th century construction by two brothers, Tang Sai-Yin and Tang Sai-Chiu. It also served as a school in the mid-20th century. Like its twin next door, it was declared a monument in 2001.

The Yu Kiu Ancestral Hall was in the process of renovations when I visited. This gave an interesting opportunity to compare the two halls. They share many features, with Yu Kiu Ancestral Hall having a more ‘lived-in’ feel. It’s still very much at the heart of the community, with storerooms packed with materials for festivals and ceremonies. The layout is very similar to the Tang Ancestral Hall, with a three hall structure.

Yan Tun Kong Study Hall

After passing an intriguing walled complex on the way, I broke out Google Maps again to find the third and final Study Hall of our Heritage Trail. Yan Tun Kong Study Hall is not currently open for visitors, but I could look from the outside, and read the Heritage Trail guide to find out more.

Also known as Yin Yik Tong, this Study Hall is in Hang Tau Tsuen Village. As with the previous Study Hall, it also served as an Ancestral Hall, and contains ancestral tablets. It was originally a structure of two halls and one courtyard, but now has a 1950s annex at the back. From the outside I could see the auspicious figures on the roof ridge, and striking figures on the doors.

Old Well

And now we have a stop on the Ping Shan Heritage Trail that I found a little odd. It’s a well. About 200 years old. Now fenced off, and with carp living in it. I wonder if they enjoy being there? It was once the main source of drinking water for two villages.

Yeung Hau Temple

Just up from the well is one of the locations that I think best evokes what it used to be like in these clan villages. The Yeung Hau Temple is still a little outside Hang Tau Tsuen Village, in a peaceful and secluded spot. We don’t know the exact date of its construction, but it’s probably several centuries old. Major renovation projects took place in 1963, 1991 and 2002.

This is one of several temples in the area dedicated to Hau Wong. Hau Wong means “Prince Marquis” or “Holy Marquis” rather than being the name of one specific individual. However, the worshippers here believe that he was the Marquis Yang Liangjie, a Song Dynasty general venerated for his bravery and loyalty. This Hau Wong having taken refuge in Kowloon, it’s perhaps not a surprise that most Hau Wong temples are found in Guangdong.

The three bays in the temple contain figures of Hau Wong, the Earth God To Tei, and protector of expectant mothers Kam Fa.

Sheung Cheung Wai

We’re down to the final few sights now, and making our way back towards the MTR. This is Sheung Cheung Wai, the only walled village on the Ping Shan Heritage Trail. It’s not possible to see inside, but there are other walled villages you can enter in Hong Kong, often for a nominal fee.

Sheung Cheung Wai has a few typical features of walled villages in the area. It’s symmetrical, enclosing rows of houses within a grey brick wall. It once had a moat for protection, controlling comings and goings through the sole entrance. Even without taking a look inside, you can see the blend of tradition and modernity in the contemporary houses peeking over the wall.

Shrine of the Earth God

I promised you another Earth God shrine, and here it is. Known generally as To Tei Kung and locally as She Kung, altars to this deity are common in Chinese villages. They were often built just outside villages as a protective measure. Like this one and the one we saw earlier, they may contain a few offerings, incense burners, small statues, and other items of worship. Those with gable walls with “wok yee” design (like the handles of a cooking wok), as seen here, denote higher status.

Tsui Sing Lau Pagoda

It’s the penultimate stop now, and it’s a good one! We’re also right across the street from the MTR, so it’s not long before we head away from the New Territories once more. Tsui Sing Lau Pagoda (Pagoda of Gathering Stars) is Hong Kong’s only ancient pagoda. It was built by Tang Yin-Tung more than 600 years ago.

Originally, this pagoda stood at the mouth of a river. Its purpose was to ward off evil spirits through the application of Feng Shui, and to prevent flooding. Its auspicious location also gave clan members a helping hand in their Imperial examinations. What a building!

Today, it’s much lower than the current street level, and looks a bit lost amidst the surrounding roads. Inside, there isn’t much to see: a small shrine and an out of bounds staircase. It’s a striking building from the outside, though, and a reward for making it this far on the Ping Shan Heritage Trail.

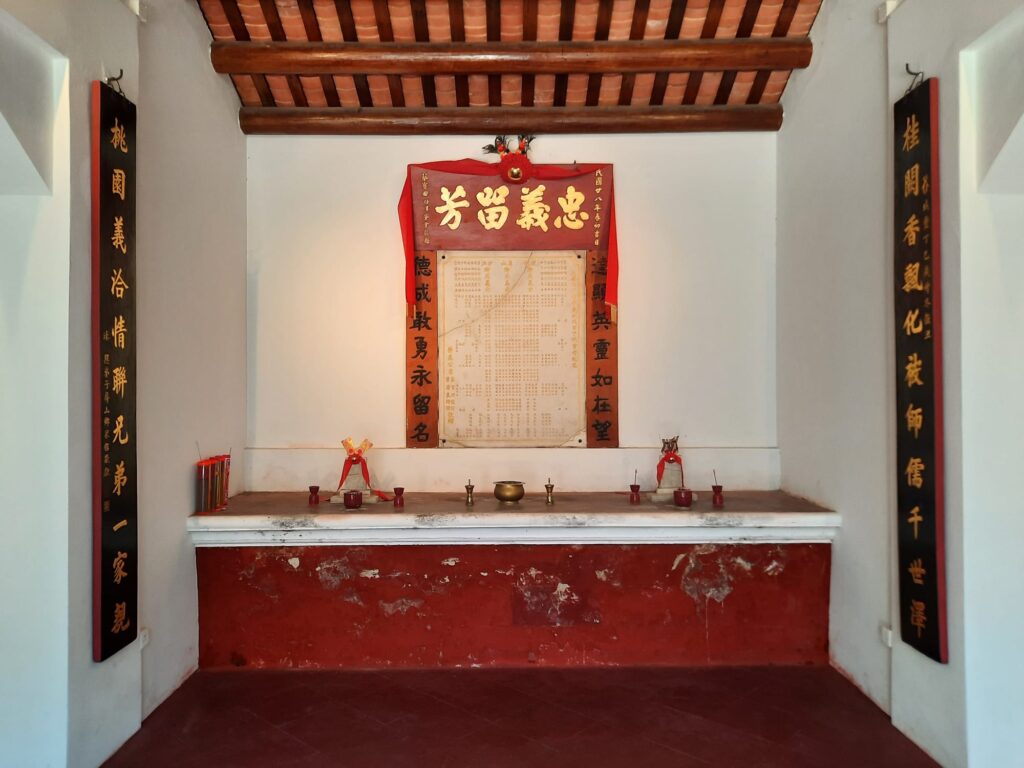

Tat Tak Communal Hall

We made it! It’s the final stop! And again it’s a unique building within Hong Kong, the only surviving purpose-built Communal Hall. This building had several functions: a meeting place, place of worship, and management office for a local market. It was the work of Tang Fan-Yau, and completed in 1857. This may be one of the sites of armed resistance against the British takeover of the New Territories in 1899.

Now that we’ve seen a few halls of different types, the structure is familiar. Two halls, one at the front and one at the back, and three bays. The poetically-named Hall of Lonesome Consolation and Hall of Bravery were later additions in the 1860s.

Final Thoughts on the Ping Shan Heritage Trail

So there we have it. We covered only 1.6KM (add a bit more for getting lost), but saw centuries of history. And more importantly, we caught a glimpse of a way of life that has nothing to so with all those skyscrapers in the globalised city just a few MTR stops away. The Ping Shan Heritage Trail shows how traditional buildings can survive into the present and continue, in some cases, to fulfil their original function. Others, like the Study Halls and their accommodation, are no longer needed but serve as reminders of what came before.

I really enjoyed my half day on the Ping Shan Heritage Trail. It’s free to visit, and everyone I met was friendly and welcoming. I reminded myself how green Hong Kong is once you get beyond Hong Kong Island and Kowloon. And I learned a lot about how clans lived, worshipped and studied together in small groupings of villages.

In terms of my aim of getting beyond the global and into the local, the Ping Shan Heritage Trail very much fit the bill. If I am lucky enough to return, I look forward to following one of the other heritage trails on offer, either in Lung Yeuk Tau or elsewhere.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.