Exploring Hong Kong’s Heritage III: Tai Kwun

The final part of our series on Hong Kong’s heritage looks at Tai Kwun, a brand new cultural centre at the heart of Hong Kong that balances colonial roots with a contemporary outlook.

Navigating Hong Kong’s Colonial Heritage

We bid farewell today to Hong Kong, but not before finishing on a high note, with a final post about a bold new cultural centre at the city’s heart. My visit to Asia’s financial centre was a busy one culturally speaking, especially given my primary purpose here was not tourism. But I nonetheless managed to see two events at Hong Kong’s Performing Arts Expo HKPAX, learned about life in clan villages on the Ping Shan Heritage Trail, and understood more about Hong Kong’s public housing programme by visiting two very different museums in Kowloon.

Hong Kong’s public housing, beginning in the 1950s, of course has colonial roots. But the subject of today’s post, Tai Kwun, allows us to consider in more detail how this small territory is navigating its post-colonial identity. It’s been 27 years already since British rule ceased in Hong Kong, which instead became a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. One country, two systems. It would be naive to think that over 150 years of colonial influence could be easily shrugged off, though. Hongkongers are proud of their identity, and what makes them unique. And part of that identity comes from the cultural fusion of colonialism with all its connotations.

The British administration had a far-reaching impact on the territory. Colonial power relations established social and governance structures. Cultural exchange influenced the city’s language, tastes and habits. And British urban planners shaped its geography. I spoke previously about how the experience of Hong Kong today is, to a large extent, the globalised experience of a major world city. Skyscrapers, nightlife, public transport: specific to the location but not necessarily unique. And the pressure in Hong Kong to develop and redevelop available land means that the traces of what has gone before may be quickly erased. Colonial buildings, for instance, are not as much in evidence as in other former cities of the British Empire.

A Brief History of Tai Kwun

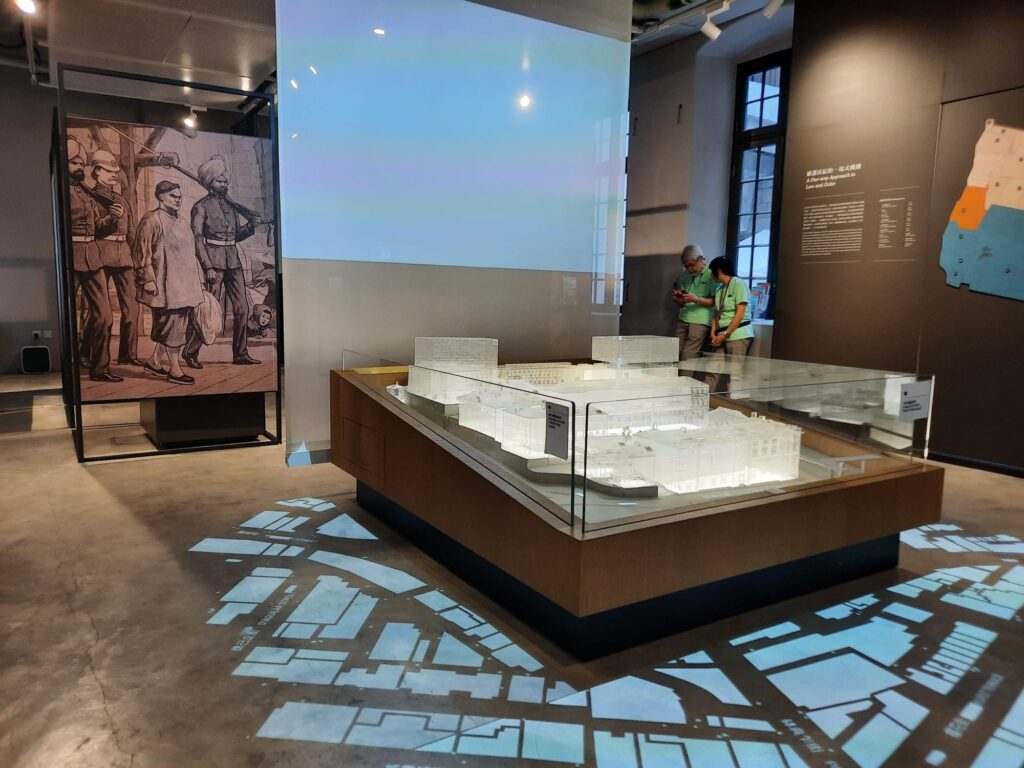

I give this as background because I found it interesting to think about these dynamics as I explored Tai Kwun. There must have been pressure to redevelop this prime site in the Central and Western District. And yet it survives as a sprawling cultural centre. Like many colonial buildings, it contains within it stories of foreign ways of life imported to new places, the coming together of different peoples, and oppression and control. The degree to which these stories surface at Tai Kwun, and how, adds an additional piece to our puzzle of Hong Kong’s unique heritage.

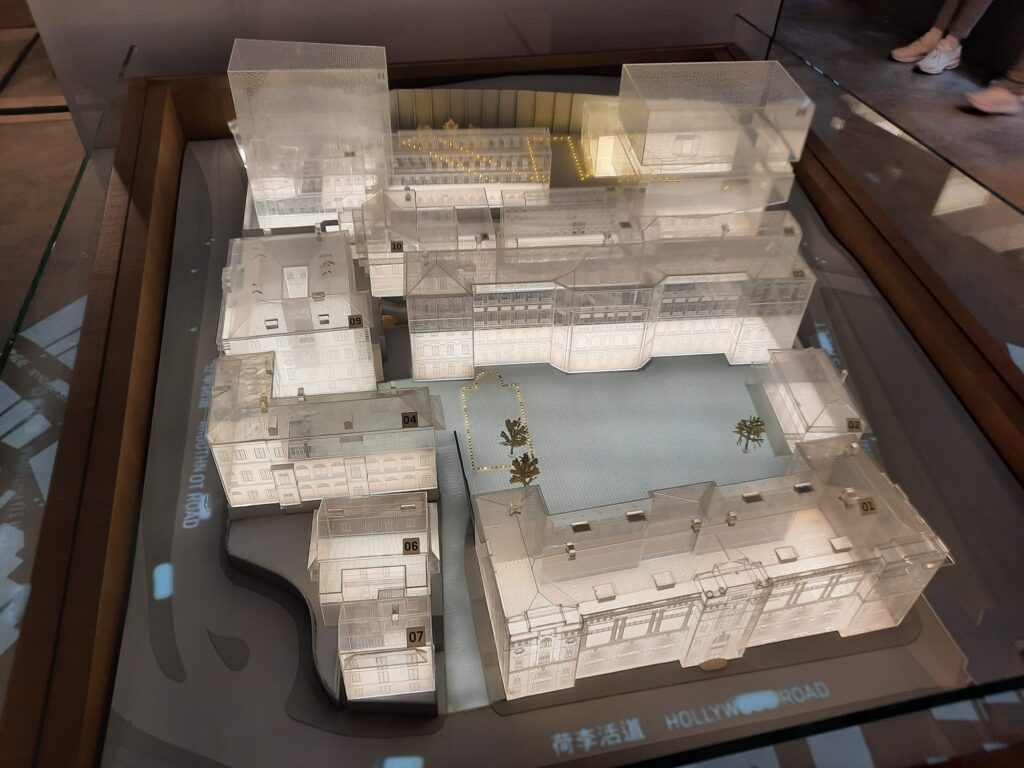

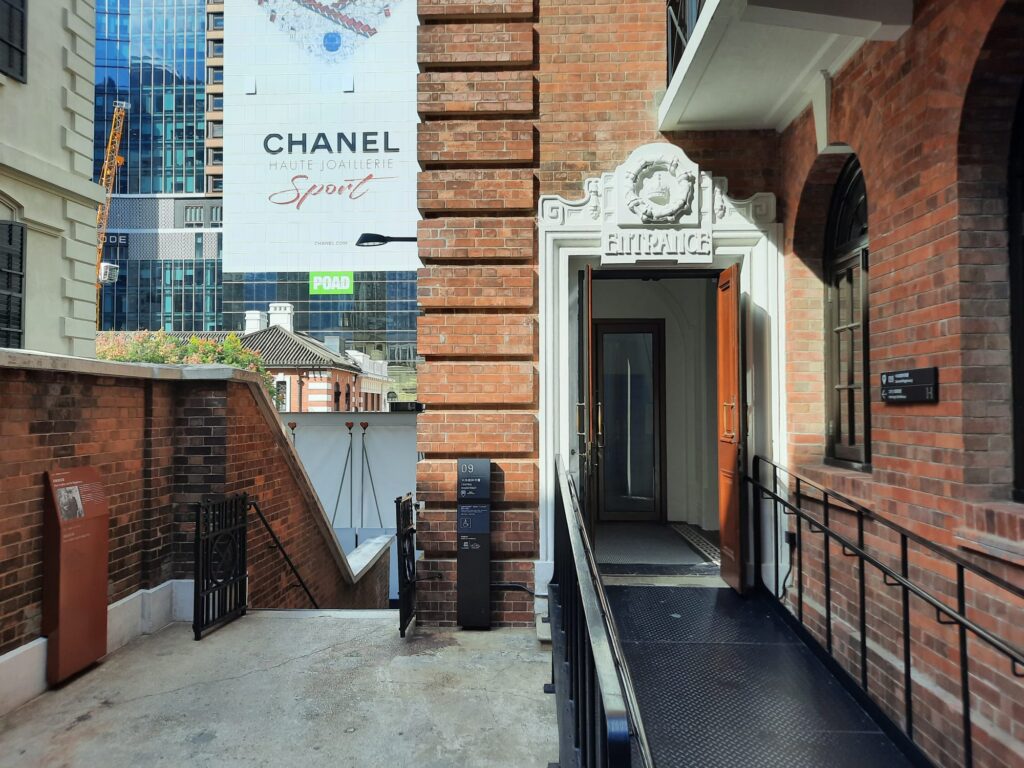

“Tai Kwun” literally means “Big Station” in Cantonese. It was a three-in-one site for the colonial government: Central Police Station, Central Magistracy, and Victoria Prison. There are 16 historic buildings, the oldest dating to 1841 (the year British rule began) and the most recent to 1925. The most recent historic building, that is: Herzog & de Meuron led the rearchitecture of the site and contributed new buildings including a contemporary art gallery.

But back to the history of the site. The Magistrate’s House came first, and included jail cells within it. Prison overcrowding led to the expansion of what became Victoria Gaol/Prison in the 1860s. It was on a radial plan, popular at the time and in line with other colonial prisons like the infamous Port Blair Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands, albeit on a smaller scale. The Central Police Station also moved here in the 1860s. A myriad of prisoners passed through, including Ho Chi Minh in the 1930s. The Japanese authorities took it over during their WWII occupation of Hong Kong. It was a site of colonial power and oppression: protests uprisings were suppressed from Tai Kwun, including anti-colonial riots in 1967.

But policing and justice have changed over the years. Eventually, Tai Kwun was no longer fit for purpose. The Magistracy was decommissioned first, in the 1970s-80s. And, having been declared monuments in 1995, the whole site closed up shop in 2006. It took until 2008 for the Hong Kong Government to announce plans to transform the site into a cultural hub, and a further 10 years to achieve that aim (including delays when a building partially collapsed). The redevelopment of Tai Kwun, like a lot of heritage projects in Hong Kong, was a partnership with the Hong Kong Jockey Club.

Historic Spaces

So we’ve learned a little about the context and background to Tai Kwun. What exactly can you see and do there? Quite a lot, actually. Tai Kwun today is a mixed use space with restaurants, art and heritage exhibitions, and events. And it’s free to visit. Just check the opening hours: the restaurants are – predictably – open longer than the exhibitions.

Speaking of exhibitions, let’s start with the historic ones. My advice for visiting them is to get yourself a map and plot a route. It’s best to start with the Main Heritage Gallery in the former Barrack Block, and continue from there. The Main Heritage Gallery gives a historic overview of the site and of policing and justice in Hong Kong. Branching out from there, you can head towards preserved cell blocks. Or there is the Story of Central Police Station exhibition in the Police Headquarters Block.

For my money, the cell blocks are the most interesting historic spaces within Tai Kwun. There are two of them – B Hall and D Hall – as well as the former admissions block, F Hall. B Hall is ‘conserved as found’ – meaning it’s in largely the same state as when operations ceased in 2006. D Hall is part of the early radial prison. In both you can get a sense of the cells, see changes over the years, and see interpretation on different topics. Things like labour, clothing, rehabilitation, and immigration.

Tai Kwun take heritage seriously. A couple of quotes from a handout I picked up should suffice to give a sense of their lofty aims:

“Once a monument devoted to law and order, this space for justice, at times, was compromised by the historical realities of xenophobia, racism, and social injustice inherent in colonial enterprises. It also bore witness to on-going prison reform.”

Tai Kwun Heritage Exhibitions: Victoria Prison, exhibition booklet

“The transformed heritage site now connects all people, including the marginalised and the vulnerable. It is a visual reminder of the values of freedom, resilience, peace, and social cohesion for a sustainable society.”

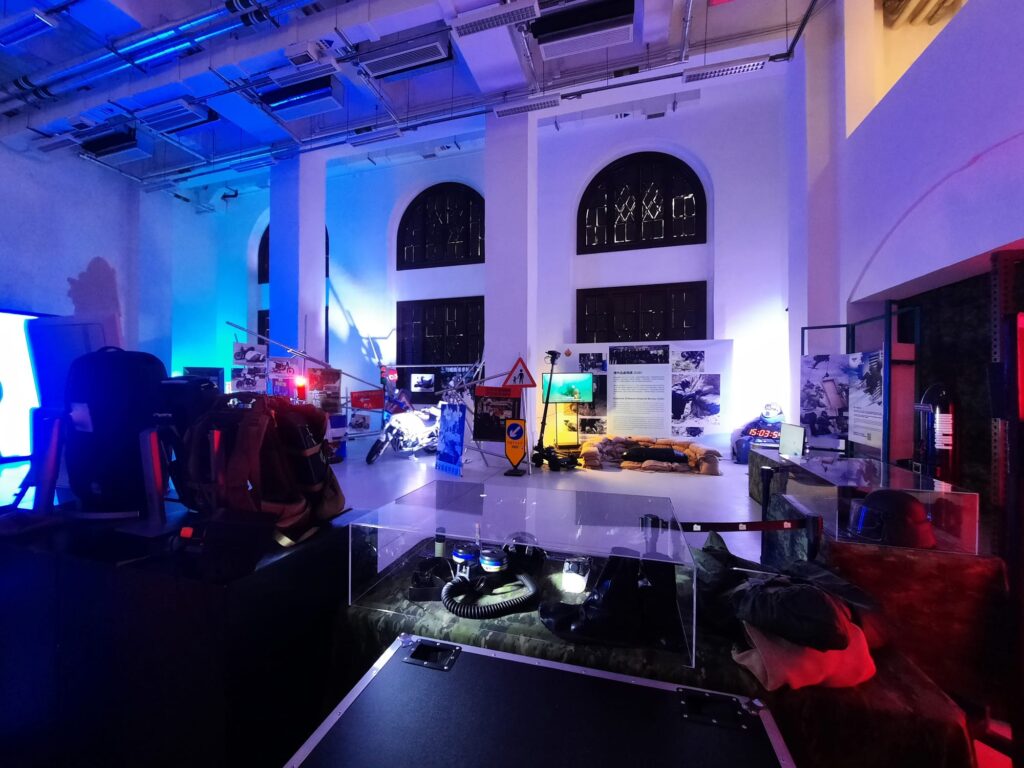

Contemporary Art at Tai Kwun

Moved by what we’ve seen in the heritage blocks of Tai Kwun, we now turn our attention to the contemporary. Contemporary art, that is, without which no cultural centre is complete. And as I mentioned, Tai Kwun has a brand new, Herzog & de Meuron-designed space within which to mount contemporary art exhibitions. The gallery is as nice as you would expect from such esteemed architects. JC Contemporary peers above some of the historic buildings, with an exterior drawing inspiration from the latter’s brick patterns.

Inside, it is again a versatile space. A striking, Instagram-worthy staircase takes you up to the galleries. On the way, you can stop off at an Asian art-focused library and reading room. Between five and eight exhibitions take place here each year. Despite decent tourist numbers, Tai Kwun focuses on its Hong Kong public in its art programme. For them, this means scheduling local artists, as well as collaborating with international institutions. There is also a lot of arts education programming around each exhibition.

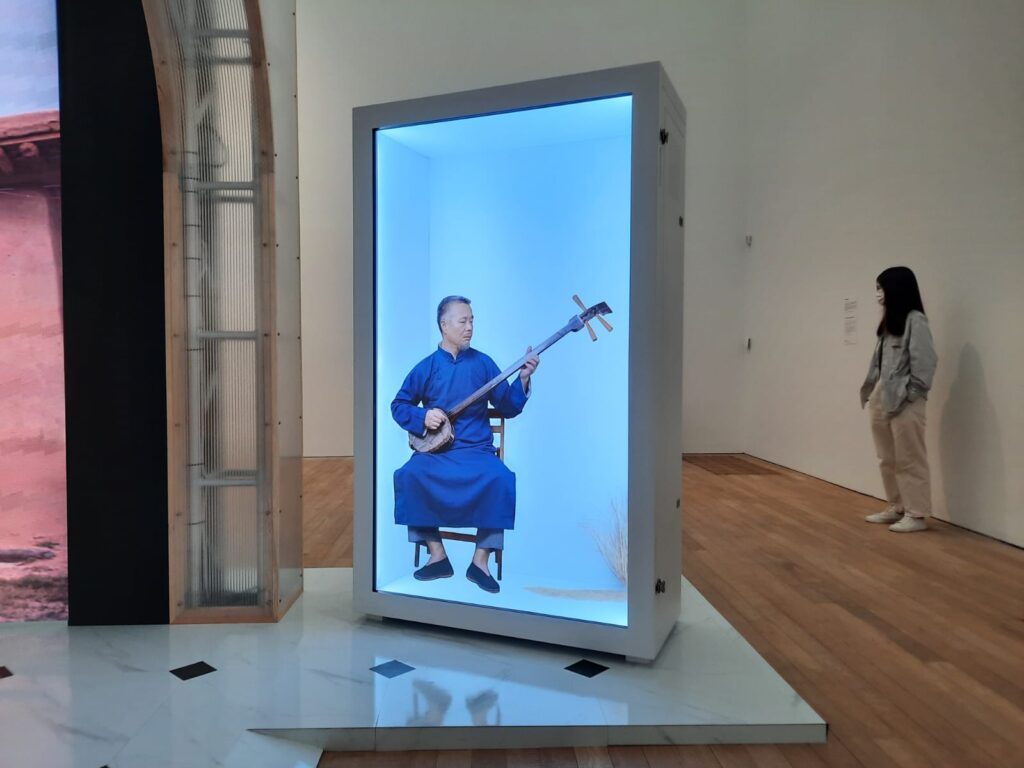

When I visited I saw Tao Hui: In the Land Beyond Living. This is the Chinese artist’s first exhibition in Hong Kong. It was a multi-media exhibition, including video, sculpture, painting and installation. Although Surrealist, it was a fascinating glimpse into different ways of life in China. I appreciated being able to see work of this calibre completely for free.

Wrapping Up: Heritage in Hong Kong

I was always going to visit Tai Kwun on my visit to Hong Kong. The photograph from above at the top of this post is the view from my hotel room. It would have been rude not to go. But since my first visit a few years ago, it’s also a place I keep returning to. The relatively low-rise buildings and open spaces feel like an oasis of cultural calm in a busy city.

And that, for me, is the point of these posts. Hong Kong is a bustling, busy place. You could easily spend a trip here working (in my case), shopping, eating, and hitting the main sights. But with just a little additional effort you can also scratch the surface and look at what lies beneath. Traces of all the different ways of life that have made up Hong Kong over the centuries. And a reminder that the past is never really forgotten. It is present in the shape of our towns and cities, the language we speak, the things we hold to be important.

You may not have time to head over to Ping Shan or to explore some of Kowloon’s smaller museums. But almost everyone visiting Hong Kong will be able to squeeze in a stop at Tai Kwun. Please do, it’s a fantastic, free resource and an opportunity to learn more about the city’s history. And as a repeat visitor I can confirm I’ve seen something different, both on the heritage and the art fronts, each time I’ve been here. I hope I’ll continue to have the opportunity to test that out!

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.