Drawing the Italian Renaissance – The King’s Gallery, London

Now this is more like it: the Royal Collection of Italian Renaissance drawings is on display in all its glory at the King’s Gallery, with plenty of detail about how these extraordinary works came to be.

Drawing the Italian Renaissance

Is this my final last minute exhibition review for the winter season? Perhaps. Unless I can sneak in just one more: there are still a few things I wanted to see and haven’t made it to… But we’re really getting down to the wire now. This one, Drawing the Italian Renaissance, for instance, closes on 9 March. Bear that in mind if you’re inspired by what you read here and fancy a visit yourself.

And I do rather wish I could go back in time a little, both for myself and in terms of what I would have suggested to you, too. If I’d been a lot more organised, what I would have suggested would be seeing this one first, and then Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael: Florence, c.1504 after that. The second exhibition (now closed) at the Royal Academy had some top-notch works and some nuanced art historical theses. But I would really have benefitted from the King’s Gallery exhibition’s more foundational approach before graduating to the Royal Academy. Oh well, can’t win them all.

I do like these exhibition pairings, though. Like A Silk Road Oasis at the British Library and Silk Roads at the British Museum. It’s just really interesting (speaking as an avowed museum geek) seeing how different institutions treat the same or similar subjects. Exhibitions are a somewhat subjective thing, so there’s often one I prefer, whether that be because I had a nicer visitor experience, connected with something within one, or preferred the curatorial approach of the other. If we have time, we’ll come back for a little compare-and-contrast at the end.

Why Are There Such Good Renaissance Drawings in the Royal Collection?

That’s an interesting question. Sort of. Maybe it depends on whether you’re also an avowed museum/art geek like me…? Anyways, I’m getting sidetracked. The Royal Collection, like exhibition appreciating, is quite a personal thing. Monarchs have been more or less free throughout history to acquire as much art, and whatever art, they want to. Within some bounds of finances and taste, I guess. But each monarch definitely brought a certain slant to what they added. And some cared more about art than others. Charles I, George III and Queen Victoria (and Prince Albert) for instance really made their mark. We’ve seen the fabulous drawings Henry VIII acquired from his court painter Hans Holbein.

Charles II’s legacy is a little different. Because I mentioned Charles I’s collecting efforts above, but he came to a famously sticky end. And Oliver Cromwell was not what you’d call an art patron. In fact, on his orders, one of the greatest art collections in Europe was sold off. When the monarchy was restored in 1660, Charles II set about restoring more things besides, including the royal art collection. He couldn’t buy back all the works that were lost. But he did his best to fill the artistic coffers once more.

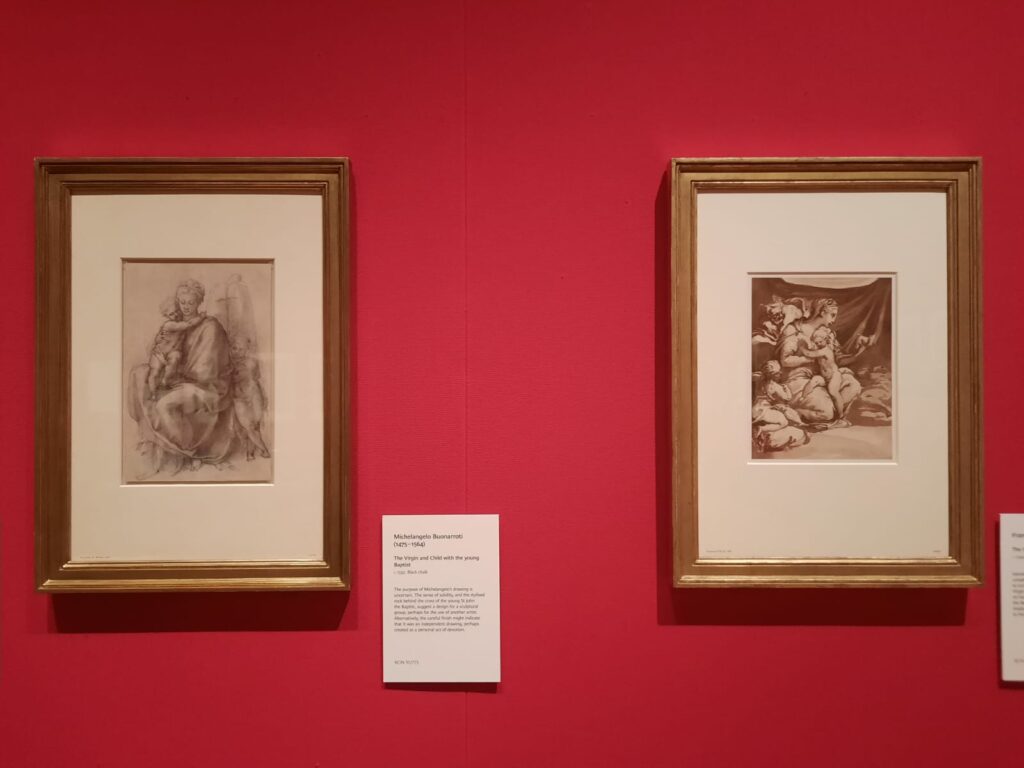

It’s not that all the Renaissance drawings in the Royal Collection today are there thanks to Charles II. But a significant number probably are. Later art-loving monarchs like George III were not so interested in the period. In any event, the Royal Collection holds a collection of Renaissance drawings fit for a king (pardon the pun). Particularly works by that familiar trio of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, but other Renaissance names too, and interesting works by lesser-known or unnamed artists. I’ll come back to a few personal highlights in a bit.

The Renaissance: A Doodler’s Paradise

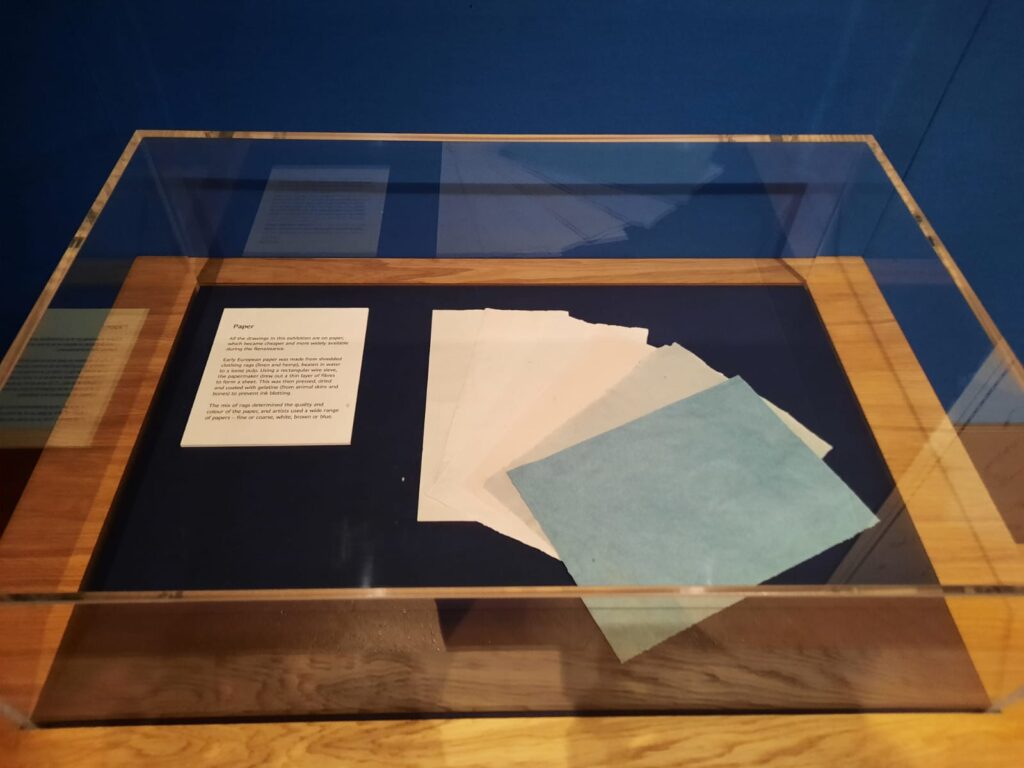

I’m being a little flippant with the title of this section, please forgive me. What I want to talk to you about now is paper. Before the Renaissance (or, more properly, before the printing press), paper was a relative luxury. Or wasn’t mass-produced in any case. Books were hand-written on parchment for the most part, for instance. But the exhibition makes the point that increased paper production to supply printing presses had the secondary consequence of allowing artists greater access to paper. They’d always used it, for instance for preparatory drawings, but now they had a bit more leeway to work out ideas, or even have a bit of fun!

It was also the sort of rag-based paper which lasts a lot better than the more recent wood-pulp paper. It’s not really an exaggeration to suggest that these Renaissance drawings could well be around for longer than some sketches artists are producing today. Definitely longer than the paper used in cheap paperbacks, anyway. And so we can continue to learn rather a lot about what these artists drew, and how they drew.

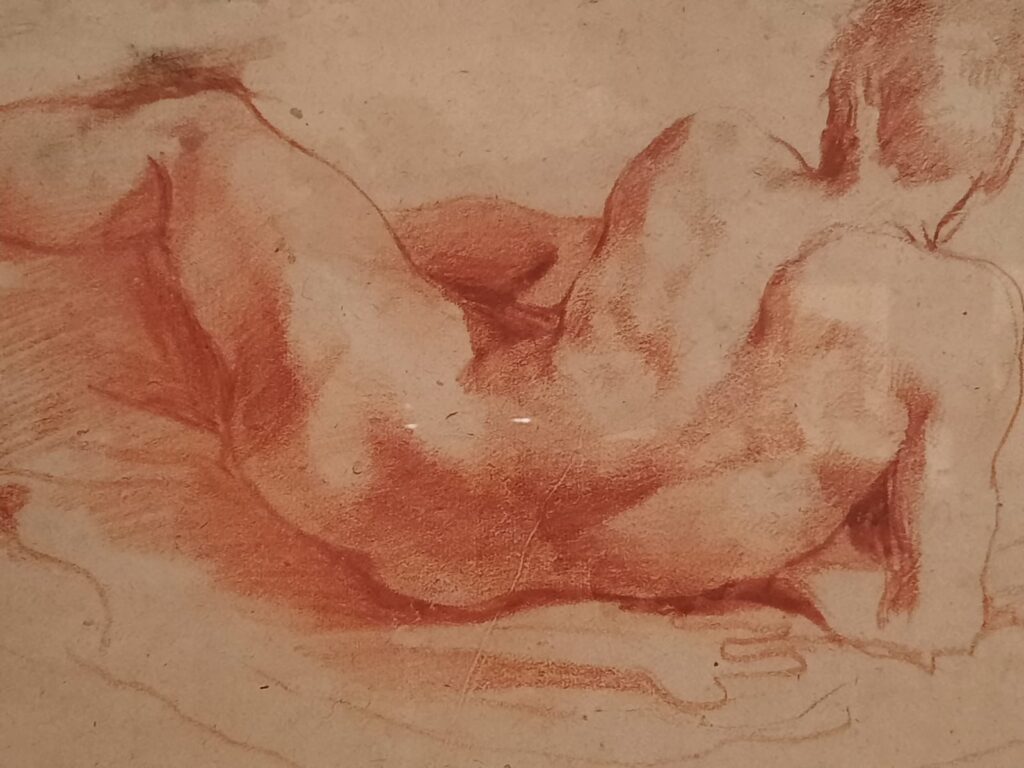

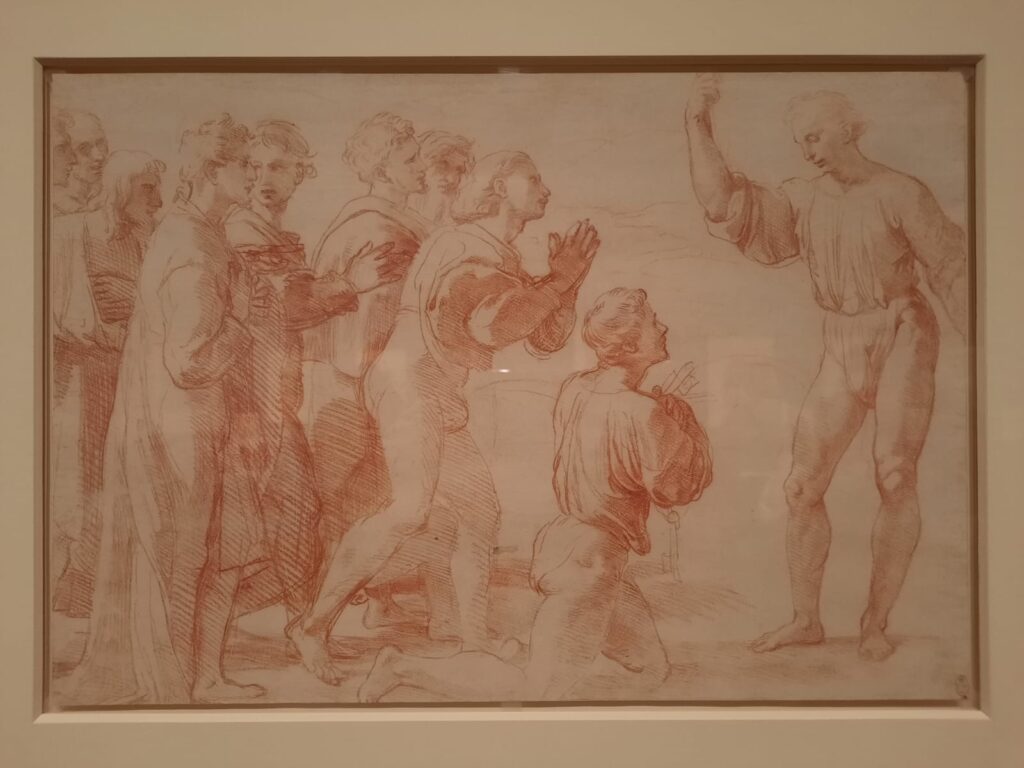

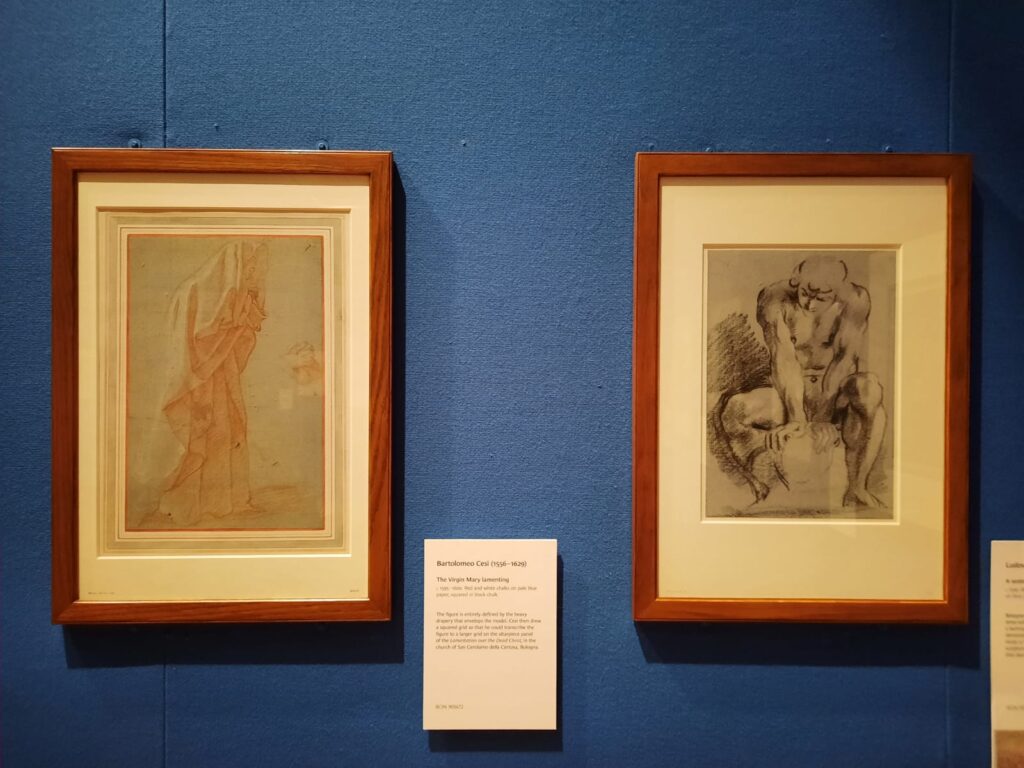

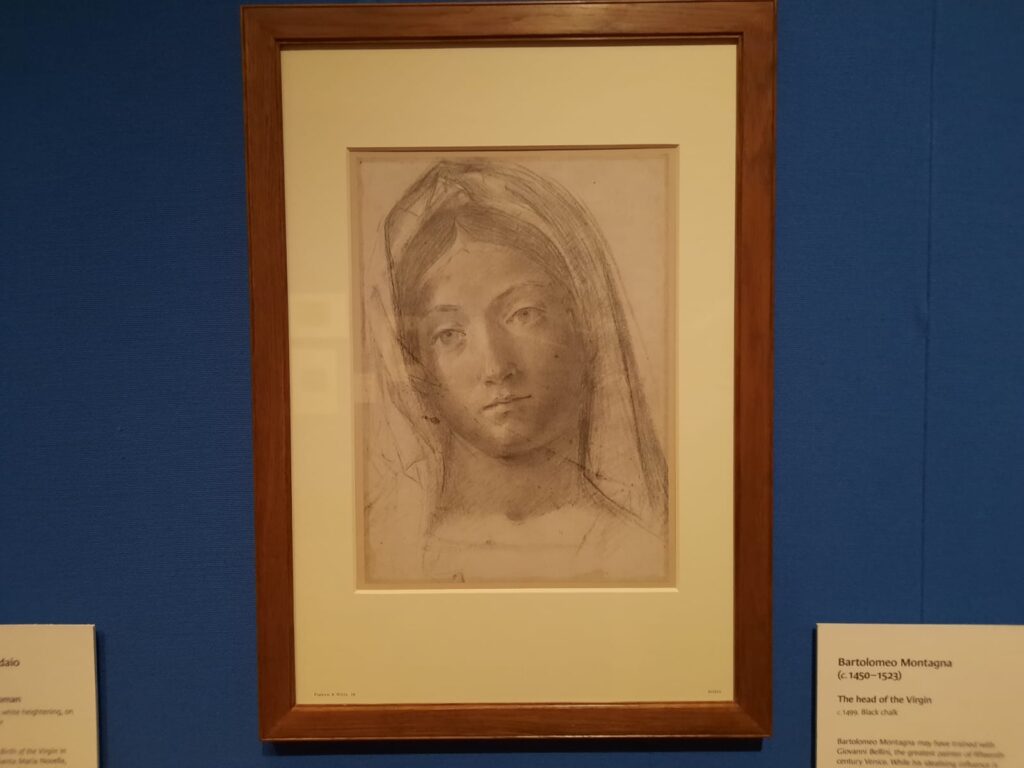

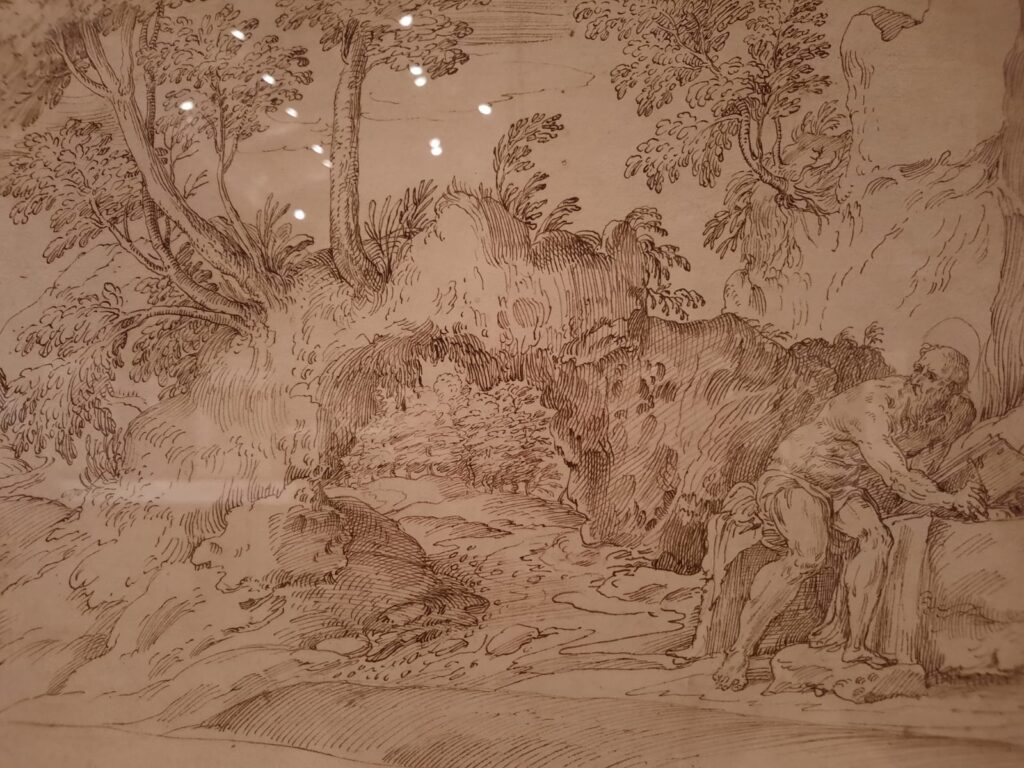

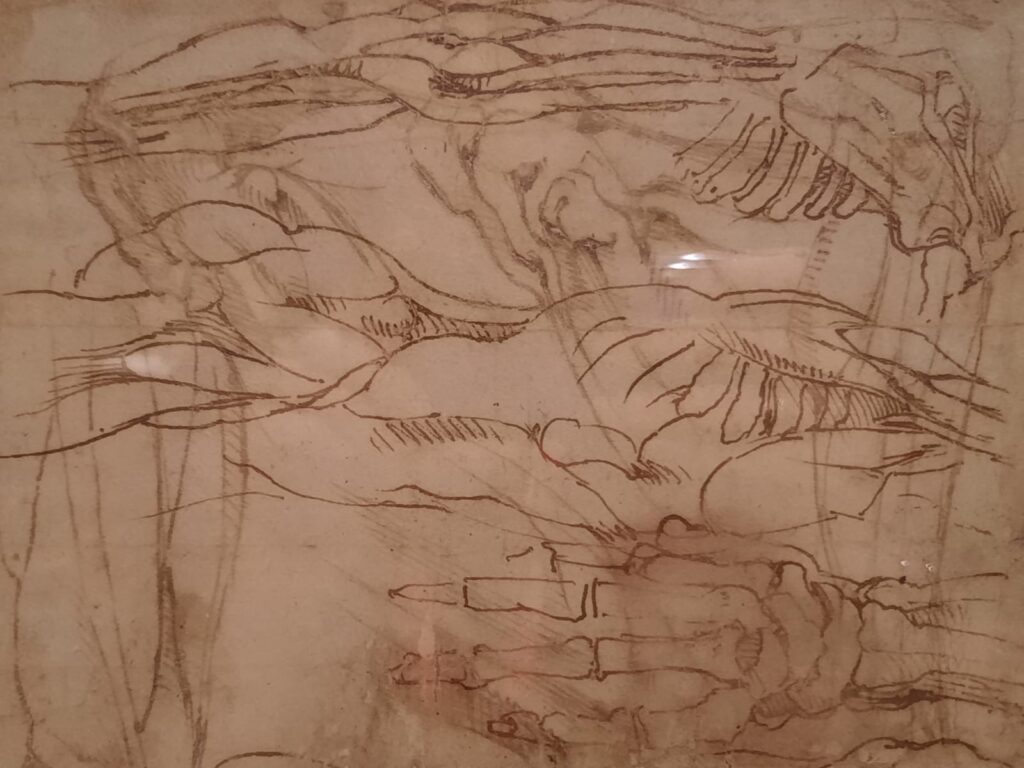

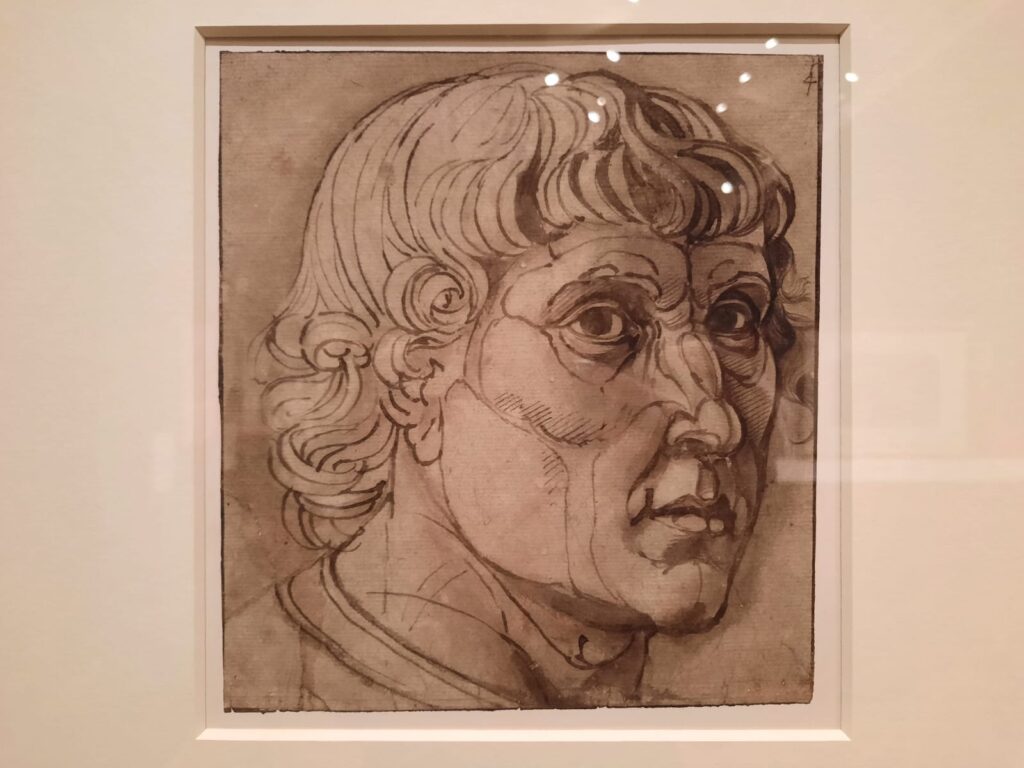

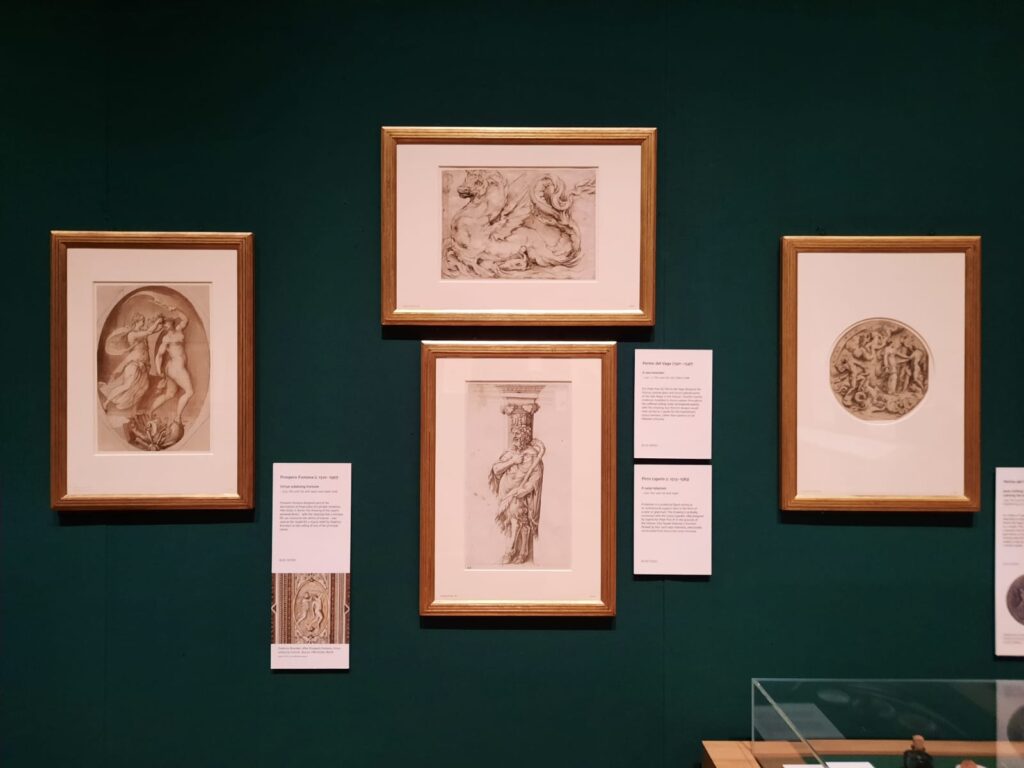

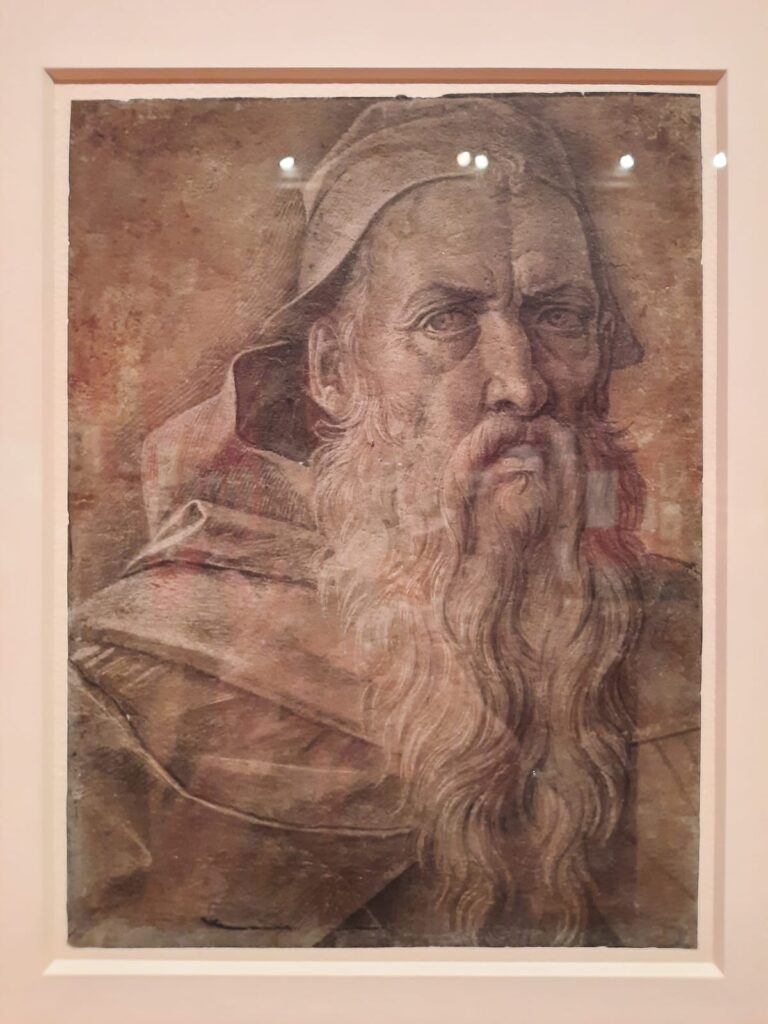

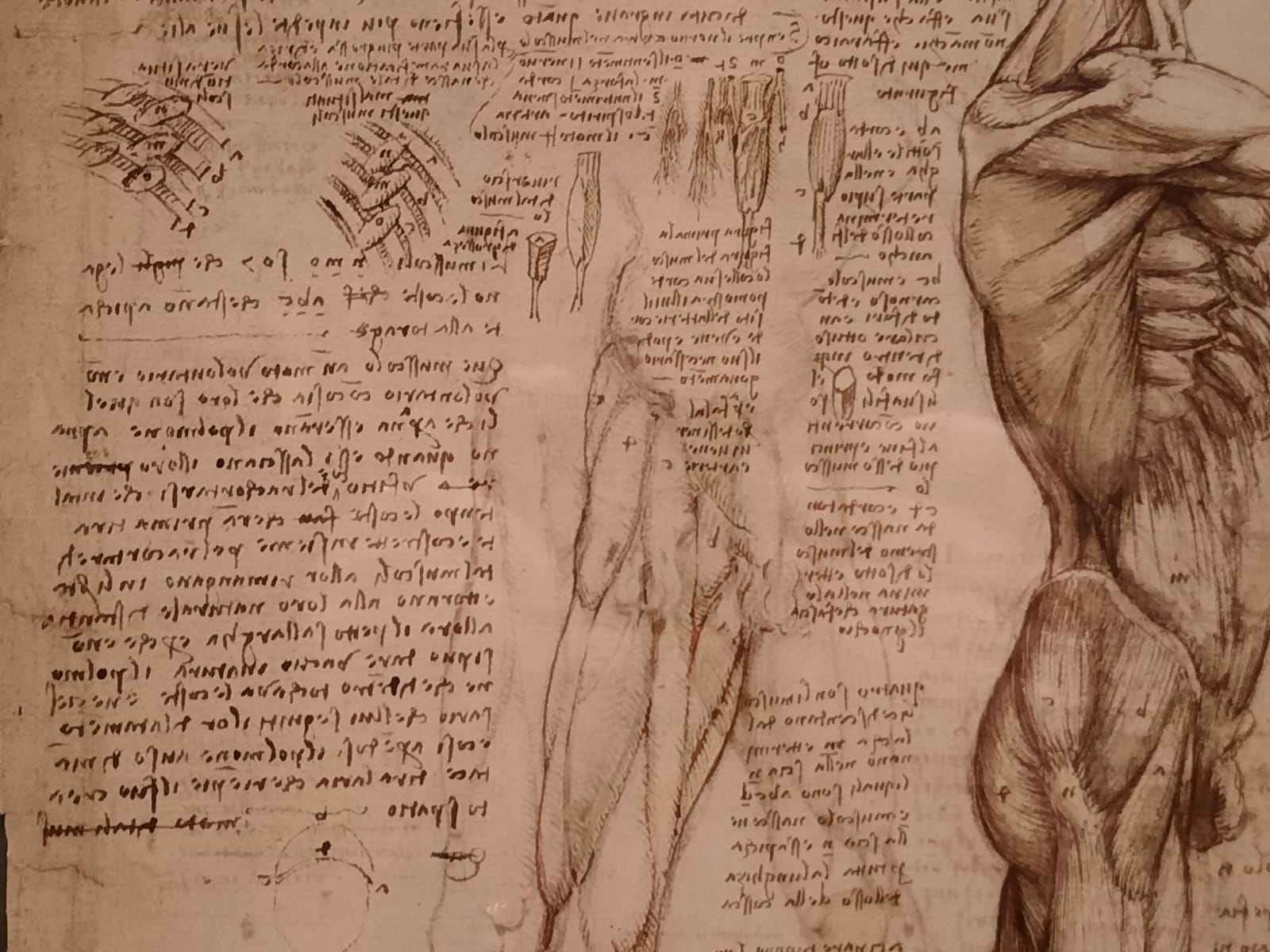

And this is where I thought this exhibition went into quite a nice level of detail. Accompanying many works is information about the techniques used. Toned paper, metal point, cross hatching, pouncing. How drawing from antique sculpture was a way for artists to learn. The fact that drawings from Bologna have heavy, dramatic lines because artists there used charcoal impregnated with oil. The role of anatomical studies. Bringing us into the present day, there’s also information about how some of the drawings have been conserved for the exhibition. And why some of them are important. For instance, I wouldn’t have thought of the fact that Renaissance designs for metal objects survive more frequently than the finished products, the latter often having been melted down in the intervening centuries. If you take your time and read the texts, there’s a real wealth of information there.

A Few Highlights

As we have established, there are many lovely drawings on display here. It really speaks to the quality of the Royal Collection actually that I’ve been so impressed by so many exhibitions of drawings here, given that I’m otherwise a little prejudiced against the level of excitement works on paper can hold vs. paintings and other media.

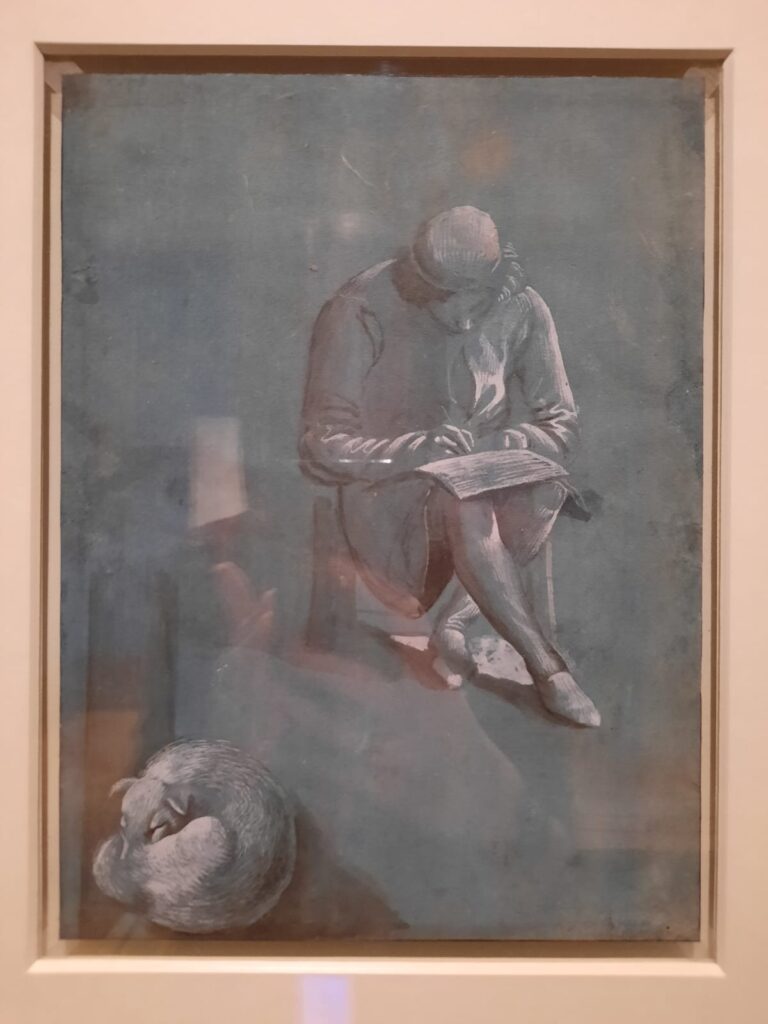

But impressed I certainly was. And right from the outset, too. The curators set the tone very nicely by starting with a drawing by an unknown artist. In it, a young man sits in an artist’s studio. He doesn’t look at the viewer: he is too busy drawing on a sheet of paper. Nearby, a dog slumbers. It’s a great way to contextualise the act of drawing within Renaissance Italy. What’s the same (the technique, mostly) and what’s different (the workshop system, the fashions, sadly the quality of the paper).

With this in mind we progress to the rest of the drawings. The groupings are largely by type. Preparatory works, portraits, studies from nature, applied arts, decoration, and drawings as finished artworks in their own right. In a liminal space between galleries there’s an interesting bit about the ways we can tell which collections or dealers some drawings came from. As I wandered the other rooms, many works caught my eye. I loved Leonardo’s quick sketches, and his more careful pages from notebooks, complete with his famous mirror writing. A page of cat sketches with a lone dragon thrown in is a real treat.

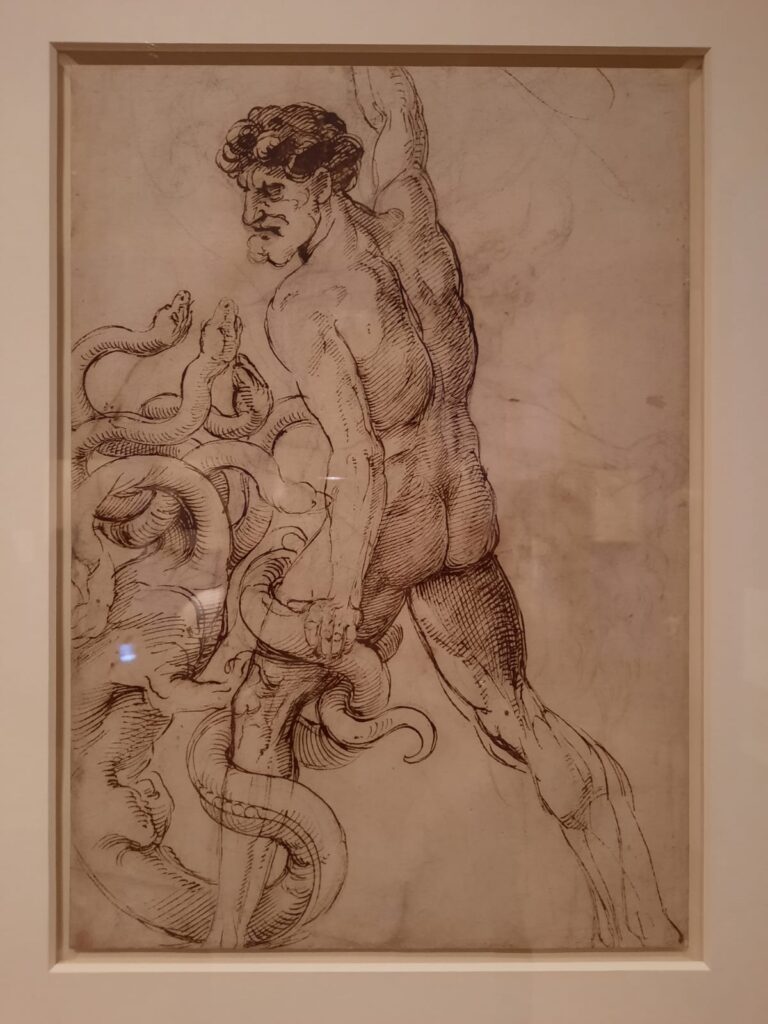

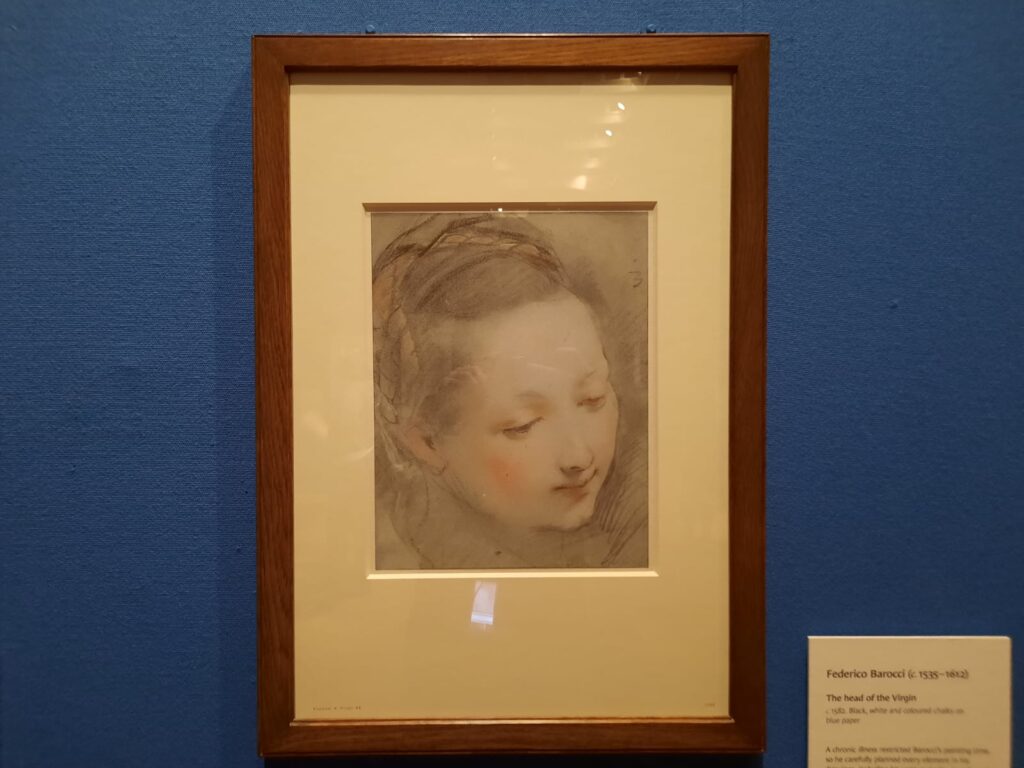

Add in some colour and Federico Barocci’s portraits are suddenly timeless. They look for all the world like the 18th century work of someone like Liotard. Or there’s Raphael’s strongly-lined drawing of Hercules slaying the hydra, the subject of an interesting ten minute gallery talk when I visited.

Final Thoughts on Drawing the Italian Renaissance

Mostly, though, I liked the drawings as a connection to the artists’ thought processes. I recall from the exhibition at the RA that preparatory sketches by Michelangelo are relatively rare, as he preferred everyone to think his genius emerged fully-formed in paint or stone. There are plenty here. The other Renaissance big hitters are well-represented too. But I equally liked seeing other artists or unknown artists work things out, hone their craft, or just make the most of the availability of paper to have some fun.

In terms of exhibitions, Drawing the Italian Renaissance is very pleasant. It’s well-organised, with different sections clearly demarcated. There’s a free audioguide, which does two things. Firstly it allows visitors to focus in on a few works out of the many on display, and imparts a different level of information. And secondly it’s a helpful way to tune out background noise in the event it’s busy during your visit.

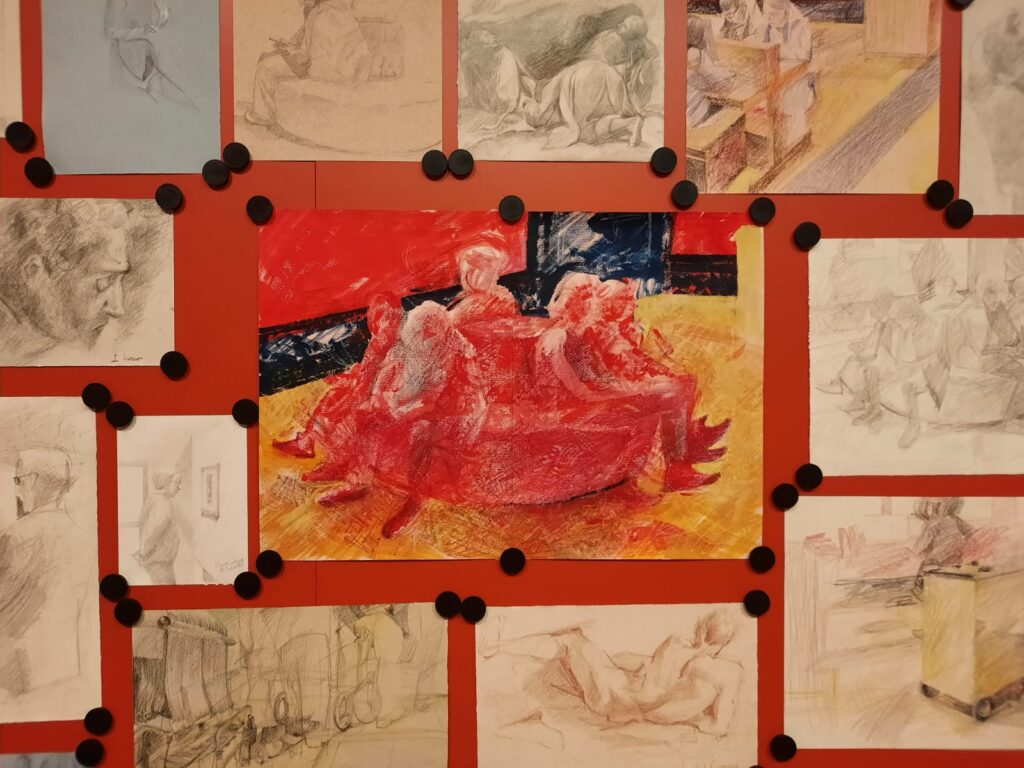

Finally, I also appreciated the King’s Gallery’s efforts to connect this historic and somewhat academic topic to the contemporary. Three graduates of the Royal Drawing School, Jesse Ajilore, Sara Lee Roberts and Joshua Pell, are artists in residence for this exhibition. They frequently draw in the galleries, and their works in response to the exhibition are in a separate room as you exit. There are also drawing tables set up in two rooms with materials and prompts to get you started. Compared to other exhibitions I’ve seen here at the King’s Gallery (and when it was the Queen’s Gallery), this feels like it might be the start of a more inclusive turn. A good omen for the future?

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Drawing the Italian Renaissance on until 9 March 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

I agree – drawing seems to suggest the artists’ thinking far more than painting.

I love when you can see different placements of a limb or a series of quick sketches of an idea: like the artist is communicating across the years or centuries.