Hew Locke: what have we here? – British Museum, London (LAST CHANCE TO SEE)

Blending artefacts and contemporary art, Hew Locke interrogates the archives and stores of the British Museum in order to ask timely and important questions about museums and their relationship to power, history-telling and colonialism.

Hew Locke: what have we here?

The Salterton Arts Review has been a little preoccupied in January, and so it was as a last-minute rush job that I managed to squeeze in to see Hew Locke: what have we here? Thank goodness I did! I knew I was going to like it, the blend of status-quo challenging questions and museological musings is right up my street. I also find it a very interesting project for the British Museum to undertake, and wanted to see it for myself for that reason as well.

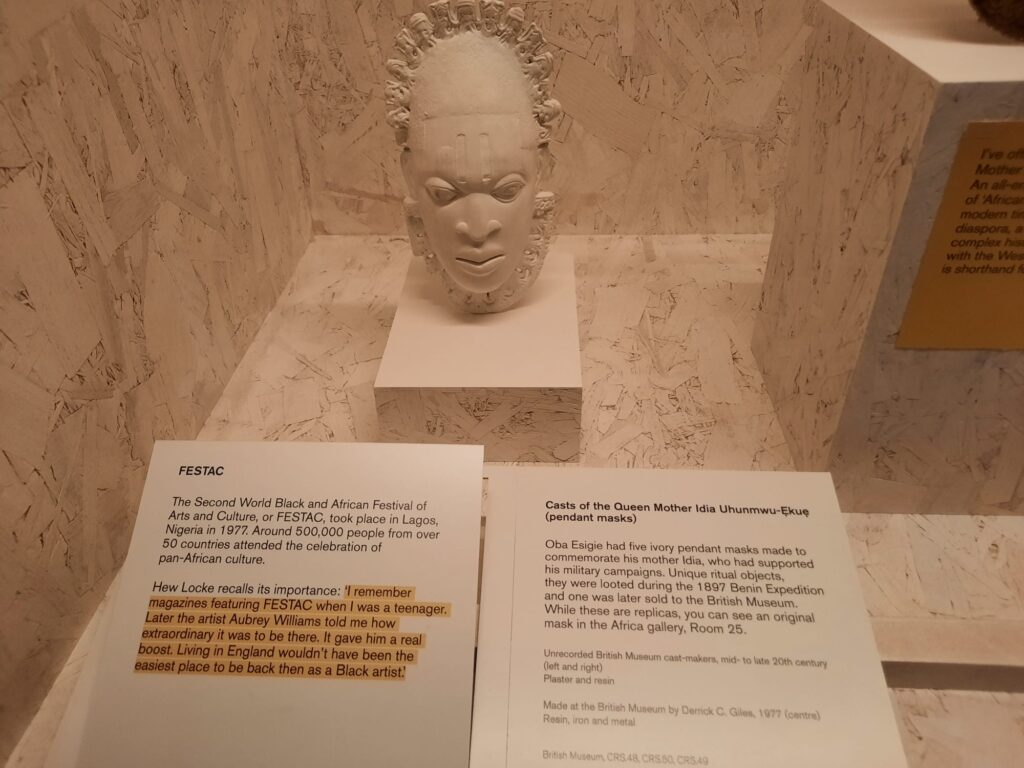

But let’s backtrack a little. Who is Hew Locke? And what is this exhibition about? The first question is relatively easy to answer. Locke is a Guyanese-British artist whose work we have encountered before. In what have we here? he takes on a dual role as co-curator and artist. As a co-curator, Locke has spent two years in the stores and archives of the British Museum, selecting objects that bring to the forefront messy and problematic stories. As an artist, he has contributed his own works to what is ultimately a beautiful exhibition despite the difficult conversations it generates.

Locke rightly says in this curator’s tour (well worth a look), it’s a collaboration that would have been unthinkable even ten years ago. It’s still surprising today. The British Museum features heavily in debates about restitution and repatriation from museum collections. Some of the most sustained and vocal campaigns, like that of Greece for the return of the Parthenon Marbles, involve its collection. Historically the opposing view has relied on one of three arguments: that returning some things might “open the floodgates”, that the world can come to the British Museum and see the collected treasures of humanity, and that it’s not legal for the British Museum to deaccession anything, anyway. Taking such a radical look at the connection between Empire, colonialism, violence, and the objects in the British Museum is thus a surprising level of transparency and open dialogue. Isn’t it?

Multiplicity of Viewpoints

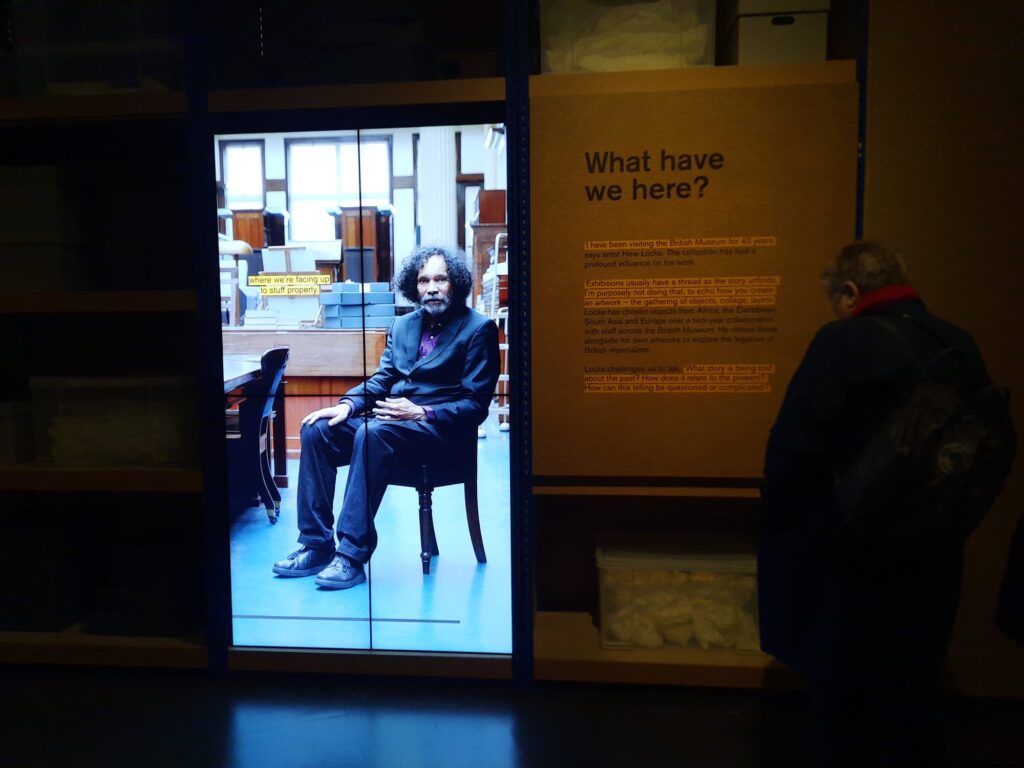

The exhibition design for Hew Locke: what have we here? contributes seamlessly to the aims of Locke and his co-curators. There are a couple of ways it does this. The first thing we encounter, for one, is a life-sized video of Locke, explaining his intentions and encouraging us to explore the exhibition freely and bring our own histories to it. As we enter the exhibition space, we know we can wander and ponder, creating connections and questioning the objects, their juxtapositioning, and the words used.

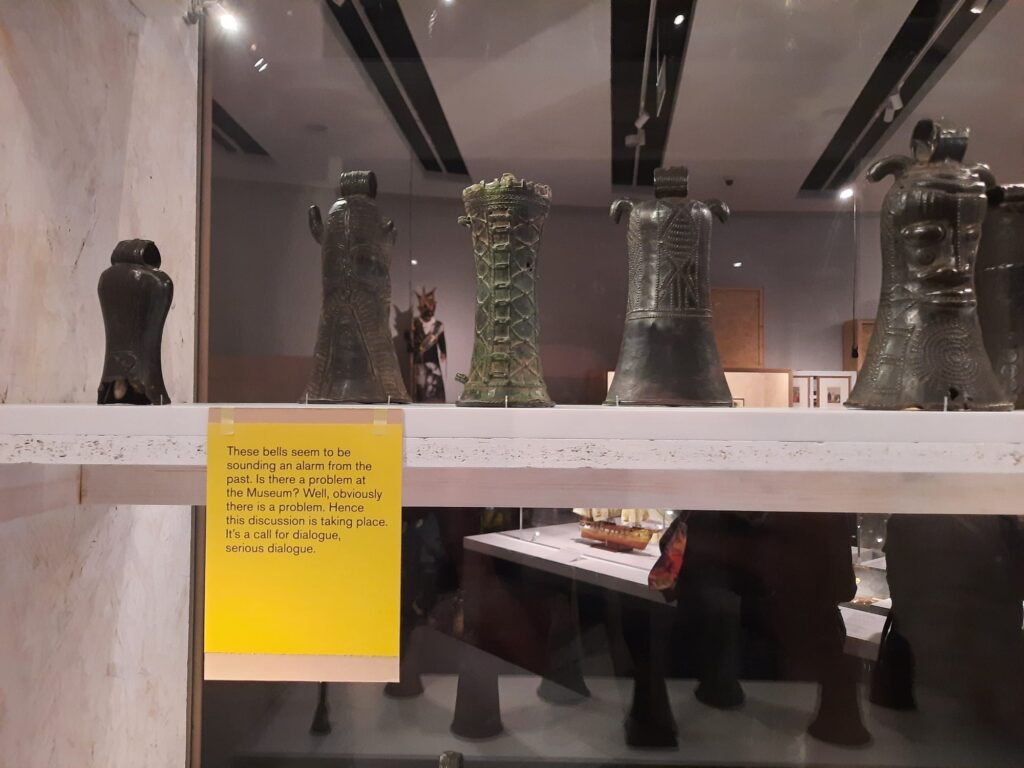

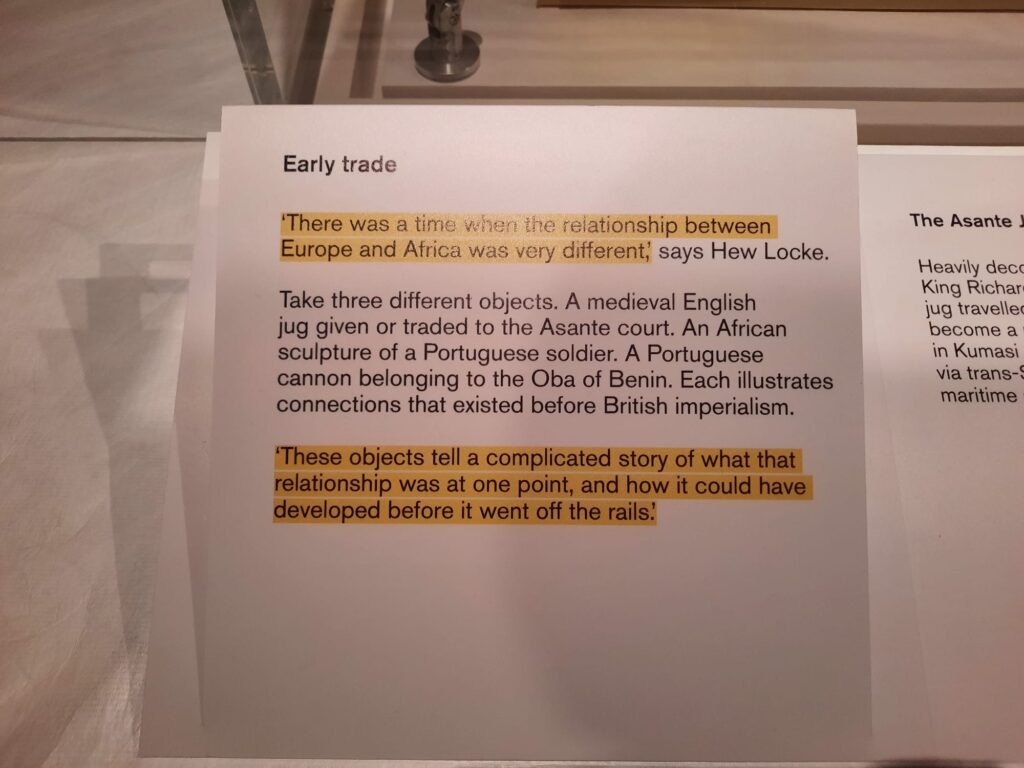

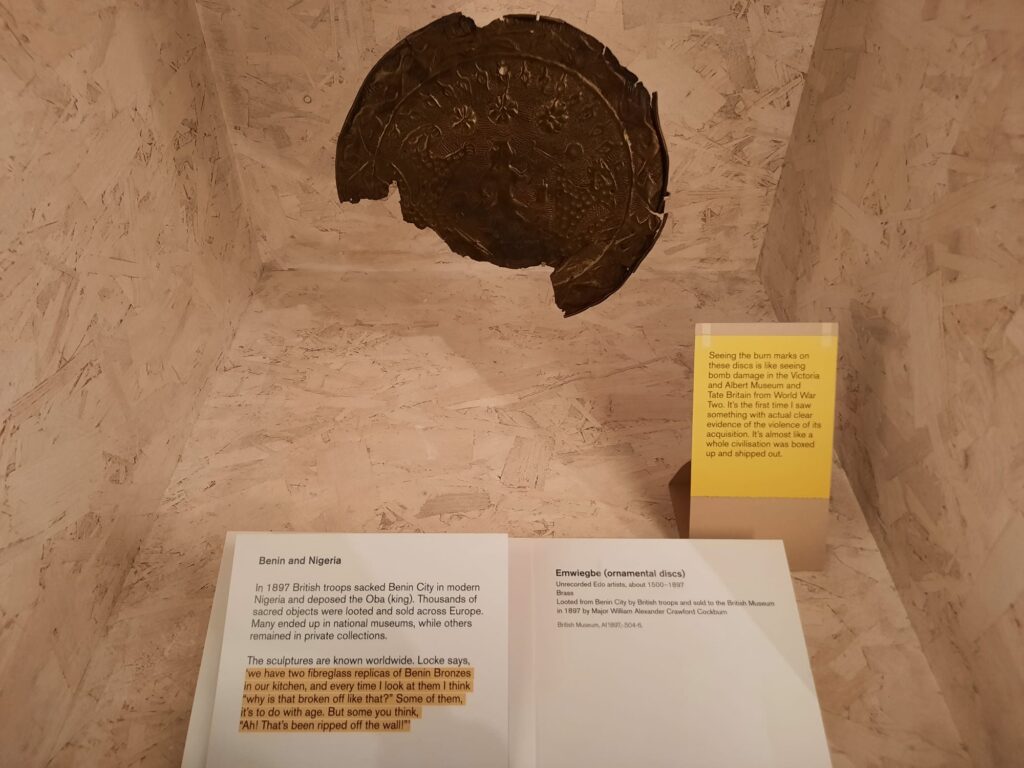

Those words are another of the excellent choices. For each object, there is a typical (“neutral”, although that’s a loaded term and nothing is truly neutral) label written by museum staff. Next to this are Locke’s thoughts, quotes he’s found, or explanations behind the selection of particular objects. Important details are highlighted in yellow. Immediately we are noticing alongside Locke, while also thinking about that idea of museum neutrality, and what it might conceal.

Both the design and the texts encourage a personal, non-hierarchical approach to the exhibition. There are already two different points of view (at least) per object. And one is intensely personal. So we know that we’re not being told an “official” history by a voice of authority. We are active participants in making meaning, in a dialogue. The matrix layout underscores this. It’s not chronological. It’s not linear. Items are grouped according to what they might reveal about each other. We can choose how and when we interact with them. It’s also immensely practical in an institution which (in my opinion) oversells exhibition tickets. We’ll see a radically different visitor experience in an upcoming post.

A Favourite Model

And so we come to an old favourite, a model from the Salterton Arts Review’s university days which is relevant in many an exhibition context. I’m talking, of course, about ‘the object as data carrier’. Described by Peter van Mensch, this is the idea that an object (in a museum context) has different data layers. There are the materials it is made of and how it’s made. There is its purpose and function as an object. And then there are the stories it carries. These are not visible but are a big part of the object’s value. This exhibition is one of the best possible examples of this idea.

Let’s take a few artefacts and see, shall we? For starters, a medieval jug. So far, so ordinary (relatively speaking). But it has a remarkable story. It came from medieval England, where it may have been made for a king. Somehow or other, it ended up in the Asante court in what is now Ghana. It was a highly venerated object, as photographs show. Why is it in the British Museum? It was part of the loot of the Anglo-Asante War of 1895-6.

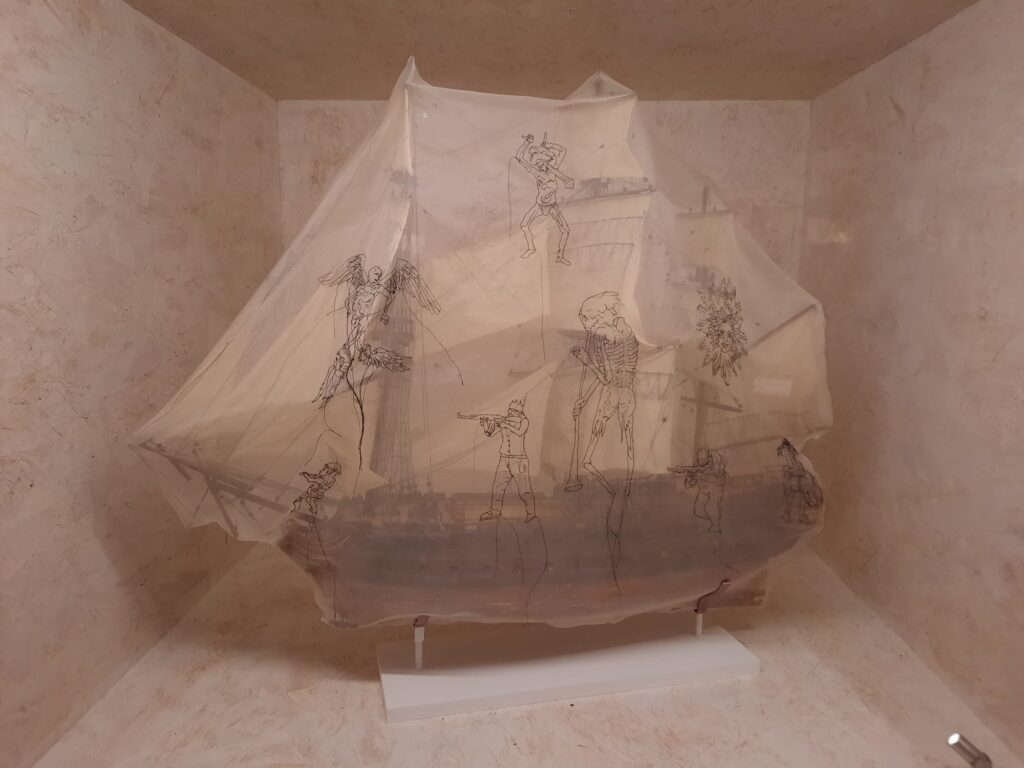

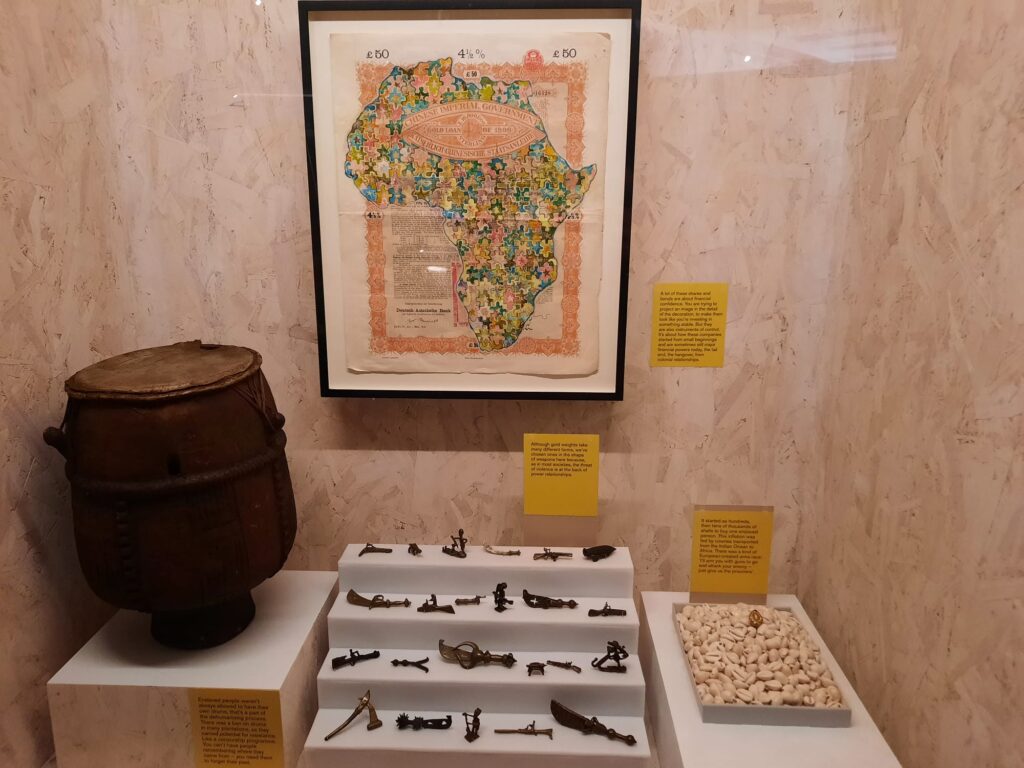

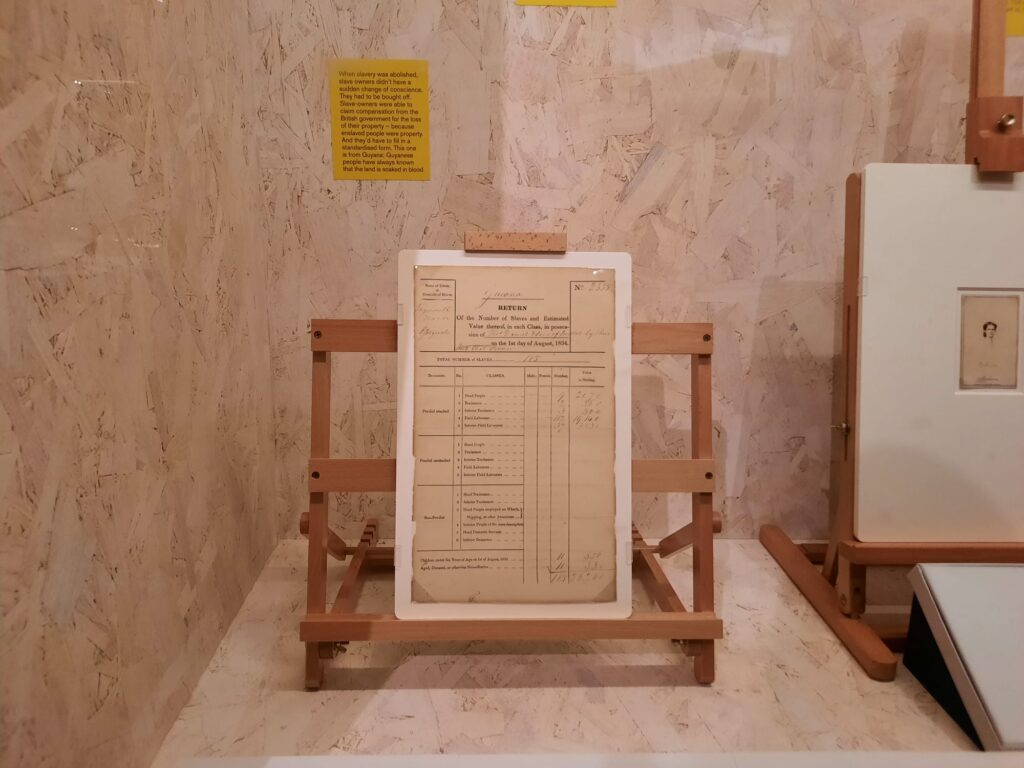

Another example is a painting of a ship, from the 1790s. It’s a nice enough painting. It’s only by understanding some of the details that you would know it’s a ship that was involved in the trade in enslaved people. With the right interpretation or knowledge, this whole other story attaches itself to an otherwise ordinary maritime painting. Likewise to trade beads, which are just colourful glass beads until you know which ones were exchanged for enslaved people.

This pattern replicates itself right across the exhibition. Many objects come from one of four conflicts: the Anglo-Asante Wars of 1823-1901; the 1867-8 Abyssinian expedition; the British military expedition to Benin in 1897; and the Younghusband military expedition to Tibet of 1903-04. Every use of ‘expedition’ there is a euphemism, they were violent conflicts rather than adventures. These conflicts are part of the history, the data attached to these objects. Other examples Locke selects or references, like the Koh-i-Noor diamond, show just how tangled and complex some of these histories and conversations are. As well as how power has shifted, ebbed and flowed over the centuries.

What Have we Next?

Having now got over our shock that this exhibition exists at all, what do we do with it? What does it mean? Are attitudes at the British Museum changing?

The answer is, I don’t know. On any count. Allowing a contemporary artist to select objects and ask such difficult questions might point to change. On the other hand, is the complexity, the ‘world histories’ angle part of the British Museum’s reasoning for keeping objects in London? Not sure. Some of Locke’s commentary addresses this directly or indirectly, for instance wondering if high quality replicas might allow some objects to return to their countries or cultures of origin.

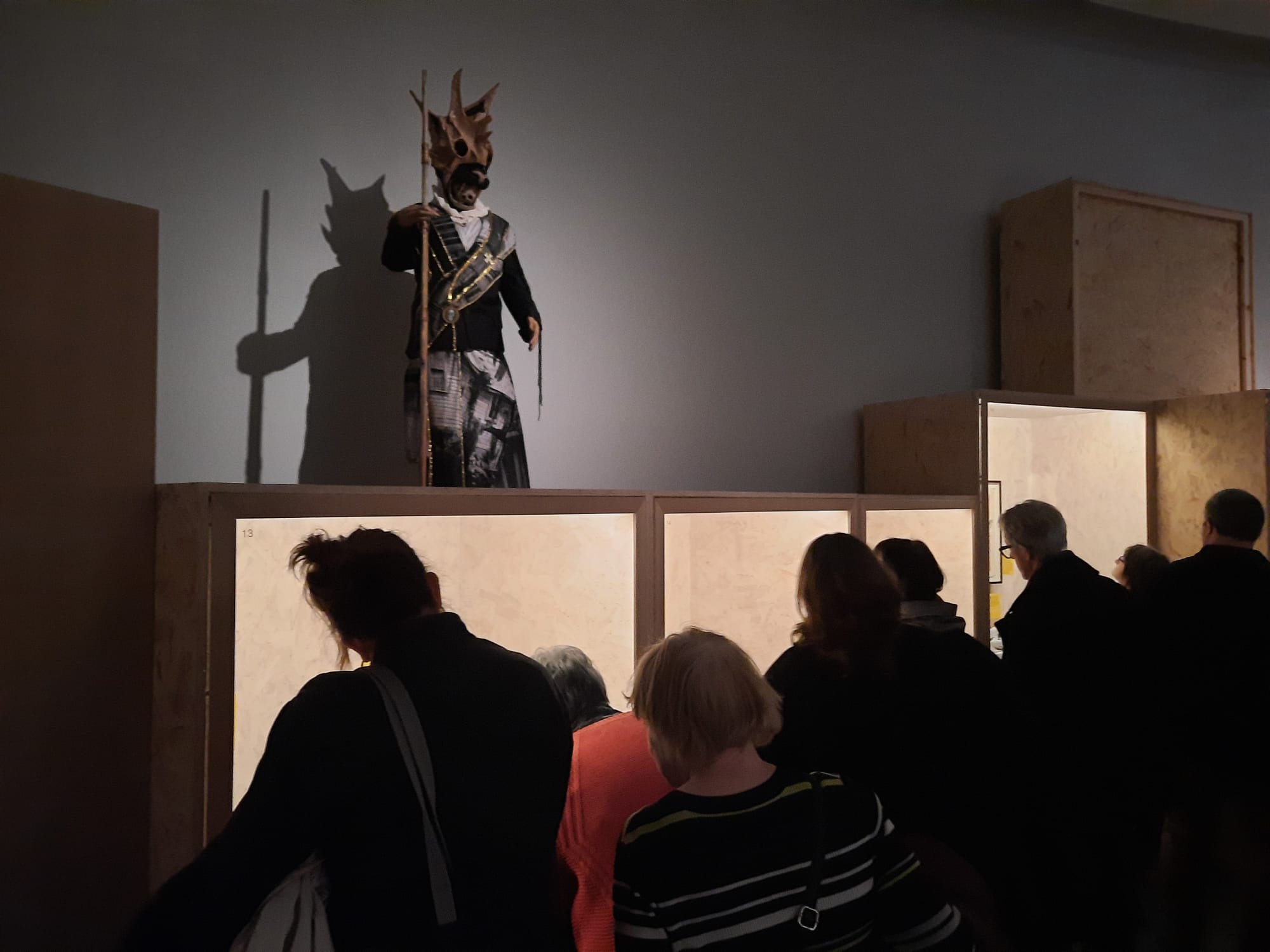

One thing that’s clear is that, as a visitor to the exhibition, you become part of the conversation. Locke’s Watchers series of sculptures stand over the display cases to remind us of this. The act of consuming culture is not neutral, we have some accountability to think and act on what we see. And, as the brilliant exhibition design once more reminds us (by evoking a museum storage environment), these objects are a few amongst millions of similarly storied objects in Western institutions. The problems aren’t small-scale, they’re enormous.

I see Hew Locke: what have we here? as part of an encouraging trend. Within the last year, I saw Entangled Pasts at the Royal Academy. And saw new ways of engaging with and presenting collections at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. As we face a reactionary moment in many Western countries, I hope major institutions can stay the course. Artists, as ever, are the voices of radical candour that will help us to do so.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4.5/5

Hew Locke: what have we here? on until 9 February 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.