Medieval Women: In Their Own Words – British Library, London

A well-structured exhibition at the British Library, Medieval Women: In Their Own Words brings to life the evidence for women’s contributions to the private, public and religious spheres of medieval life.

At the British Library Once More

After an absence of a couple of years, I have visited the British Library twice in recent months to see their temporary exhibitions. The British Library had been very busy in the interim, including with a major cyber security incident in late 2023 which is still making itself felt. Including in exhibition ticketing arrangements. When I came to see A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang a couple of months ago I took a photo on my phone of payment confirmation in order to enter. This time, for Medieval Women: In Their Own Words I was handed an A4 version of what would normally be a phone-sized QR code. It just goes to show how long-reaching the effects of such attacks can be.

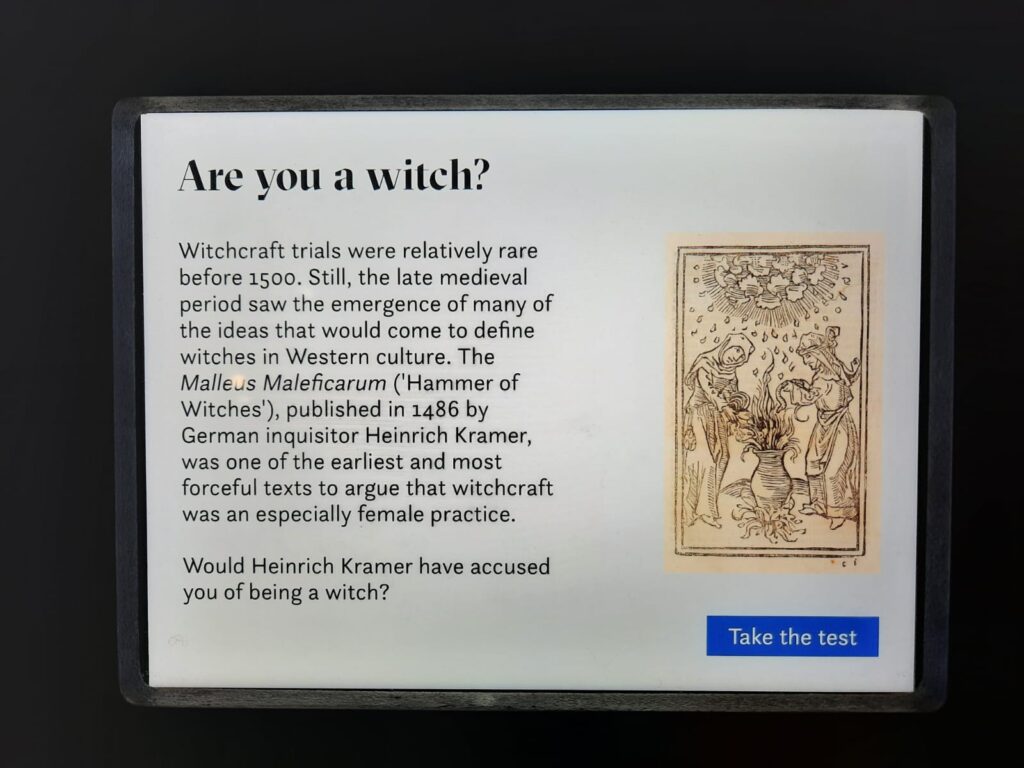

This is just a little aside, though. We’re here today to talk about that latest exhibition. It’s in the larger of the British Library’s adjacent temporary exhibition spaces. And is very interesting indeed. The exhibition website promises to introduce “the women of medieval Europe through their own words, visions and experiences”. Intriguing, especially given the low literacy rates generally in medieval Europe, particularly when it comes to women. An outcome of this lower literacy and overall lower participation in public life by women of the period is that we tend to think of medieval women in terms of a few stereotyped images. Princesses in flowing headdresses, perhaps. Nuns. Witches. Maybe some peasant women.

All of these types of women are addressed in Medieval Women. And more. The British Library have selected works from their collections (along with a few loans) which attempt to show medieval women from all kinds of different angles. And in all different spheres, as well. The result is very engaging, even when the materials occasionally feel like a bit of a stretch vis-à-vis the intended scope.

Women in Medieval Europe

It’s a fairly obvious fact that women have been about half of all humans (or slightly more) since humans have existed. But we live in a patriarchal society, at least in the West, which has long favoured a secondary role for women. Politics, business and public life are a man’s world. Domesticity and children are the preserve of women. Why bother investing, then, in a traditional education for girls? Better they spend their time on handicrafts and accomplishments designed to lure a suitor.

Things have never been quite that simple. I’m generalising wildly, and also talking about a certain socioeconomic class within society. When it comes to working class* families, women have always worked, out of necessity. That’s both in rural settings, where women participated in farm labour, and in urban settings where they took on a variety of jobs or supported their husbands in business. And, although limited, there have been opportunities throughout history for some women to take on a different kind of role in society.

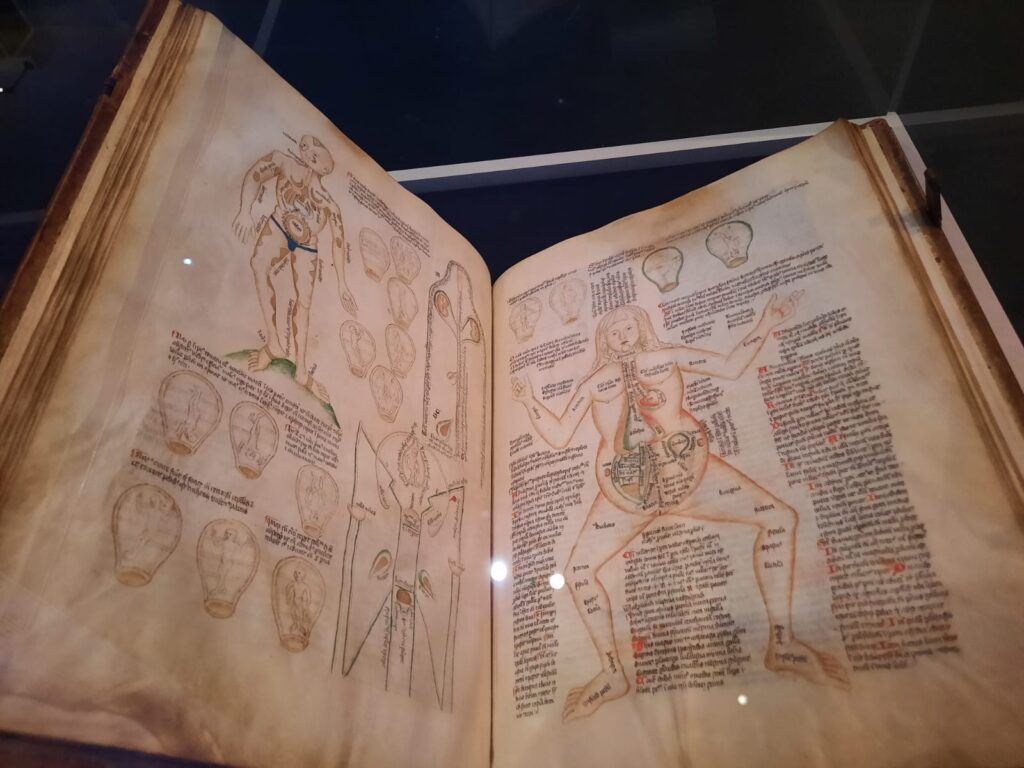

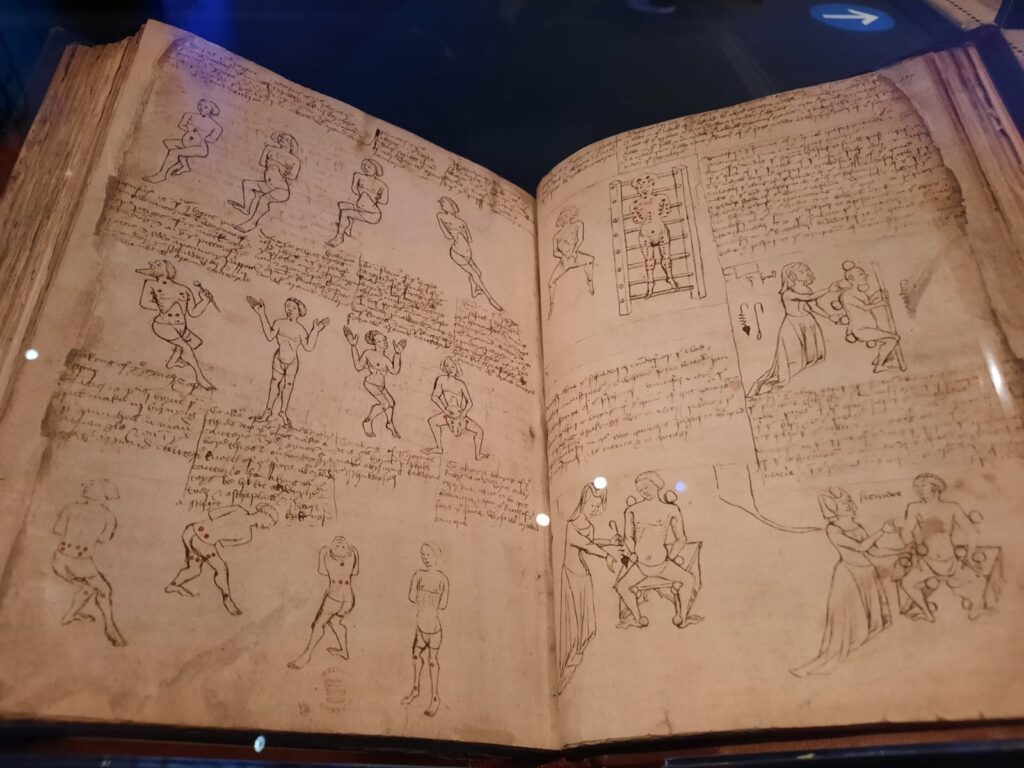

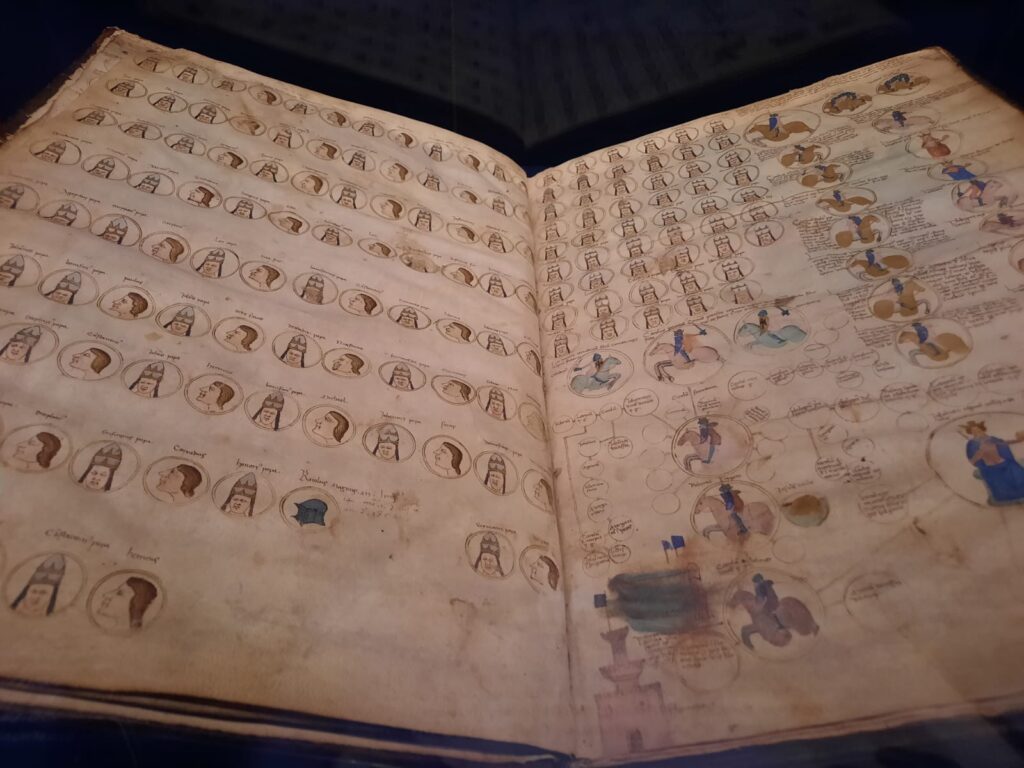

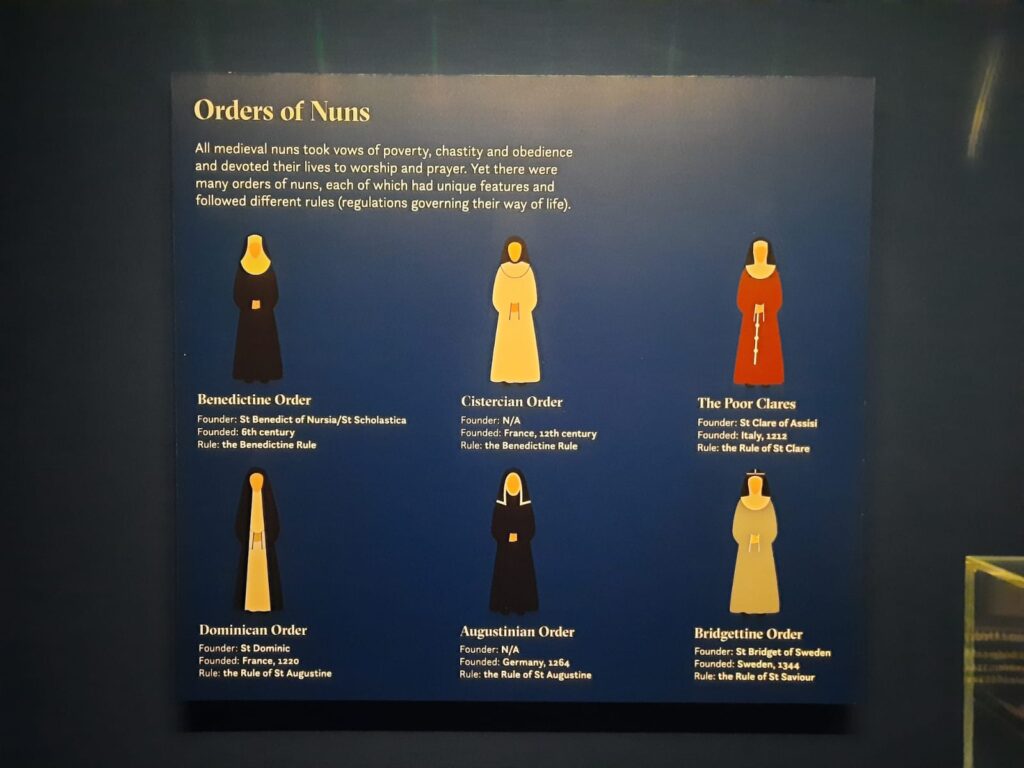

Medieval Women: In Their Own Words sets out to explore the evidence for all these contributions by first of all breaking medieval society down into its most fundamental building blocks. Private life, public life, and religious life. Private life covers domestic activities, medicine, childbirth, inheritance, friendships and so on. Public life covers rulers (one of the better ways to be remembered as a medieval woman was as a queen), but also women in business and women of letters. And religious life is mostly about nuns, abbesses and anchorites, but also includes Joan of Arc as the leader of a religious crusade.

In all of these spheres the British Library has found examples of women in their own words. But it’s not quite as simple as that.

*I use the phrase ‘working class’ a couple of times in this post. We’re mostly talking about feudal economies so it doesn’t quite fit. But you know what I mean.

In Their Own Words?

Again I’m going to categorise into three here, although this time it’s my own categorisations rather than the British Library’s.

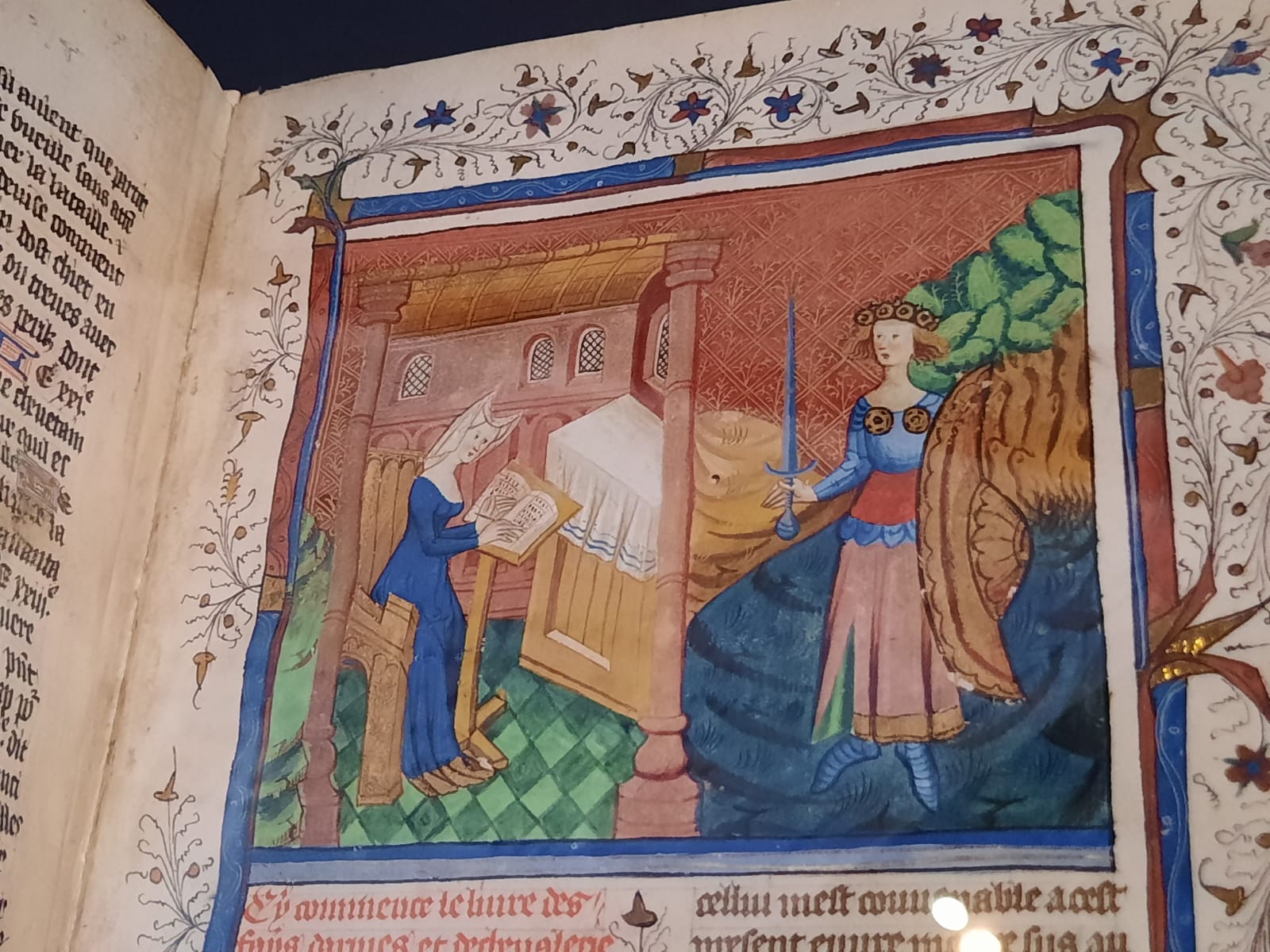

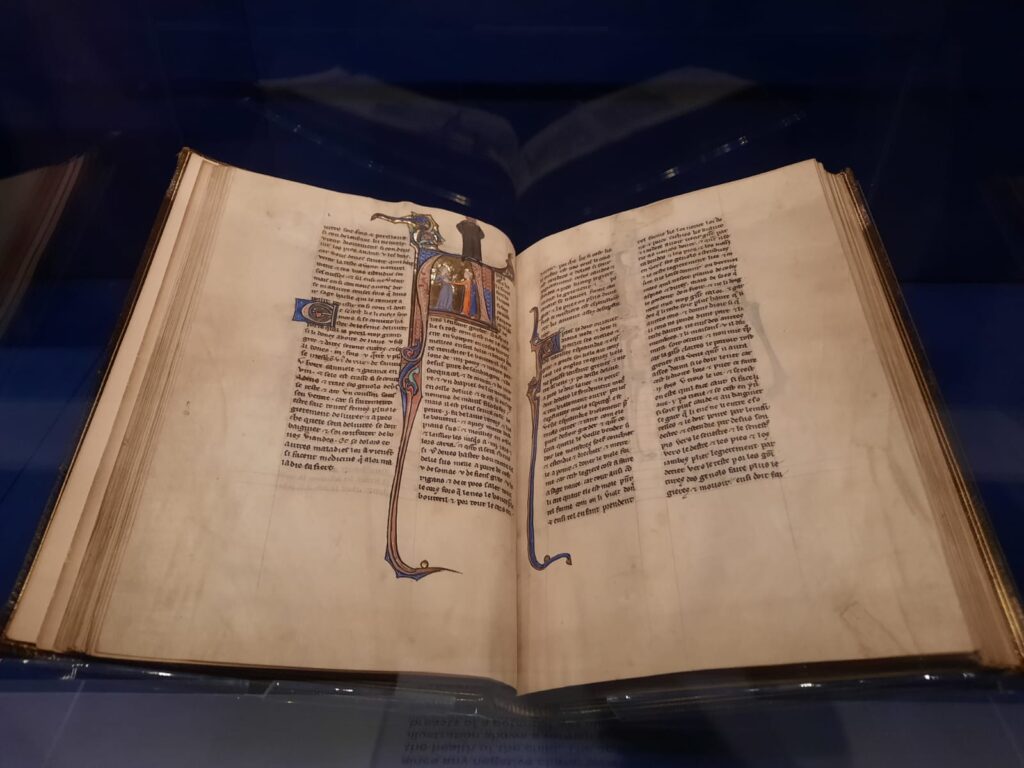

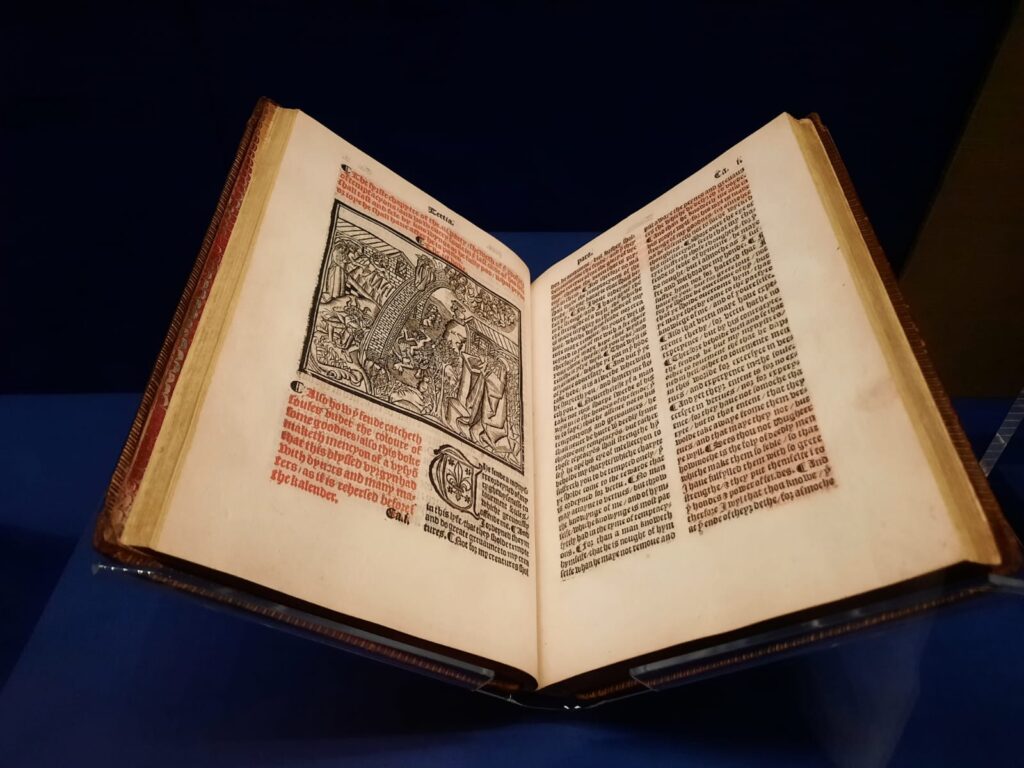

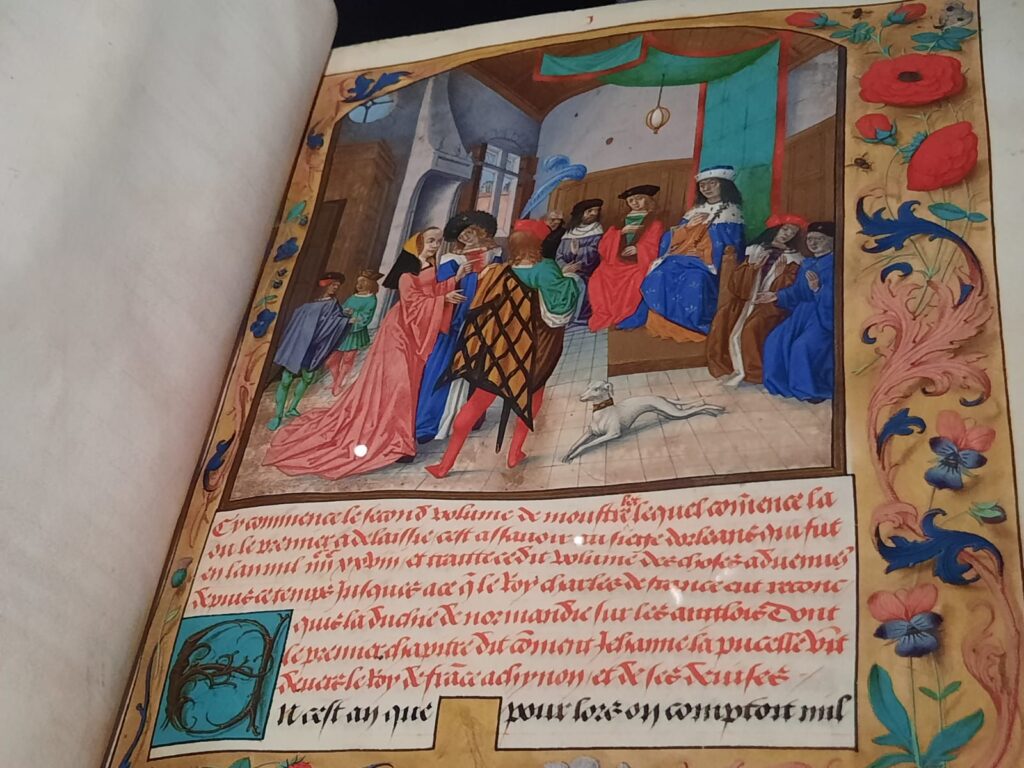

There are, in this exhibition, plenty of examples of women’s own words. Let’s start with the more obvious spheres, the public and the religious. The exhibition includes, for instance, Christine de Pizane’s Book of the City of Ladies (early 1400s). Sometimes considered the first professional female author in Europe, de Pizane built a metaphorical city out of tales of exemplary women. She served as a court writer, including for Charles VI of France, to support her family after the death of her husband. Or there is Hildegard of Bingen, an abbess and polymath who wrote, composed music, was a philosopher, practiced medicine, had visions: basically every avenue open to a medieval religious woman.

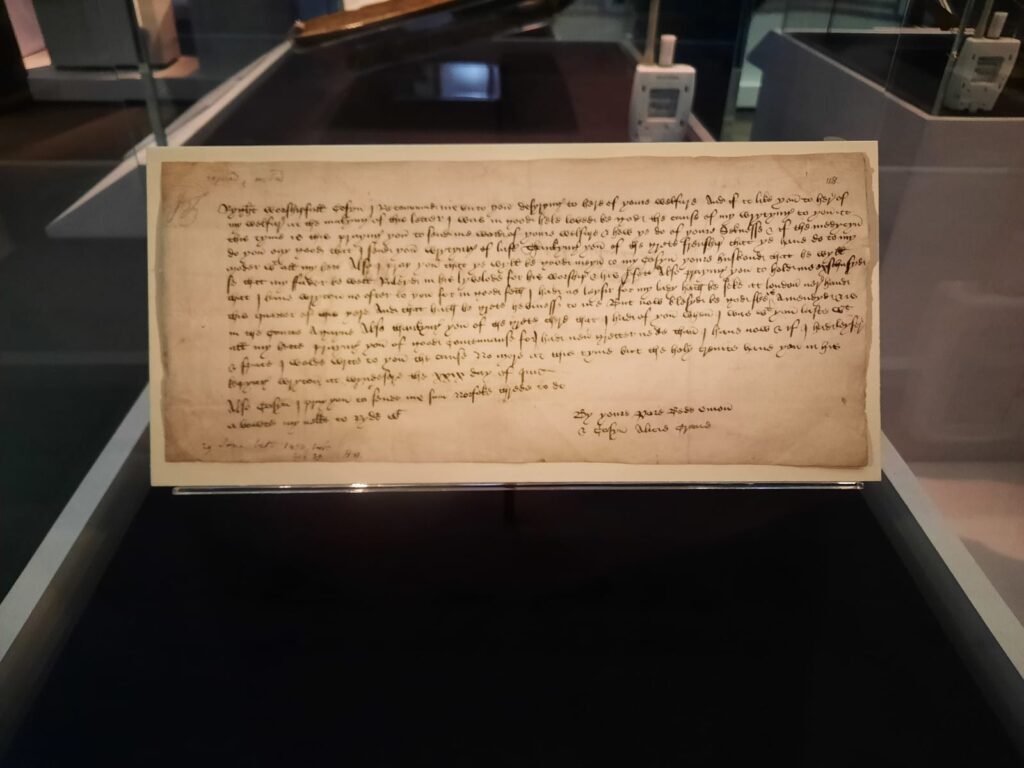

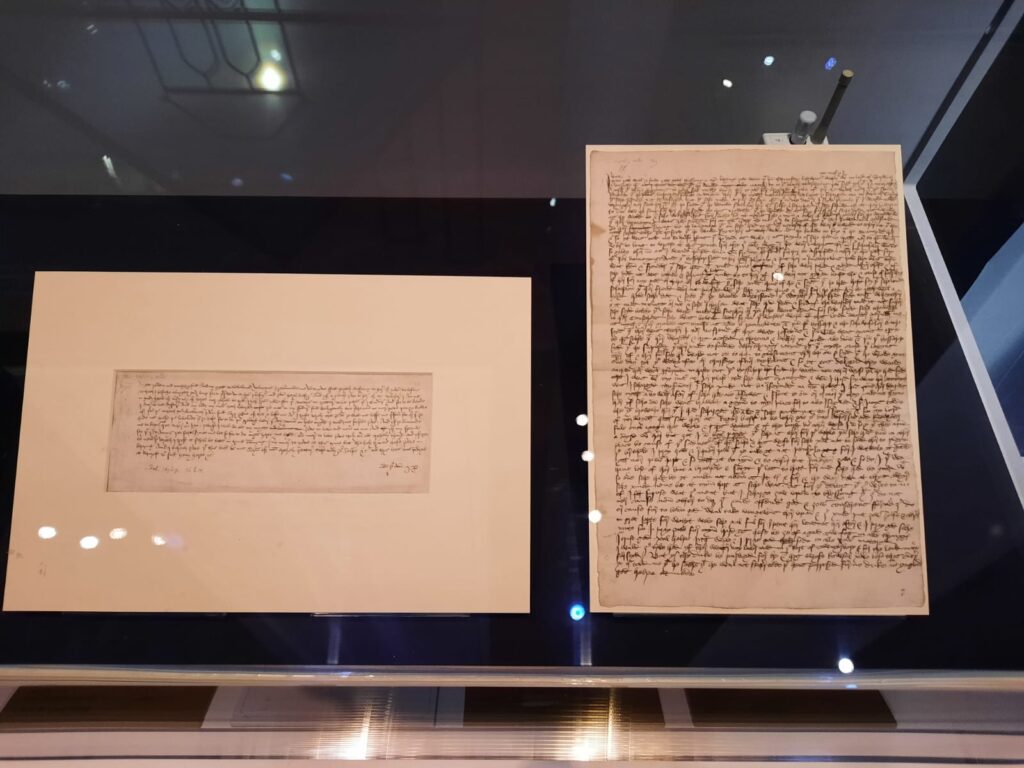

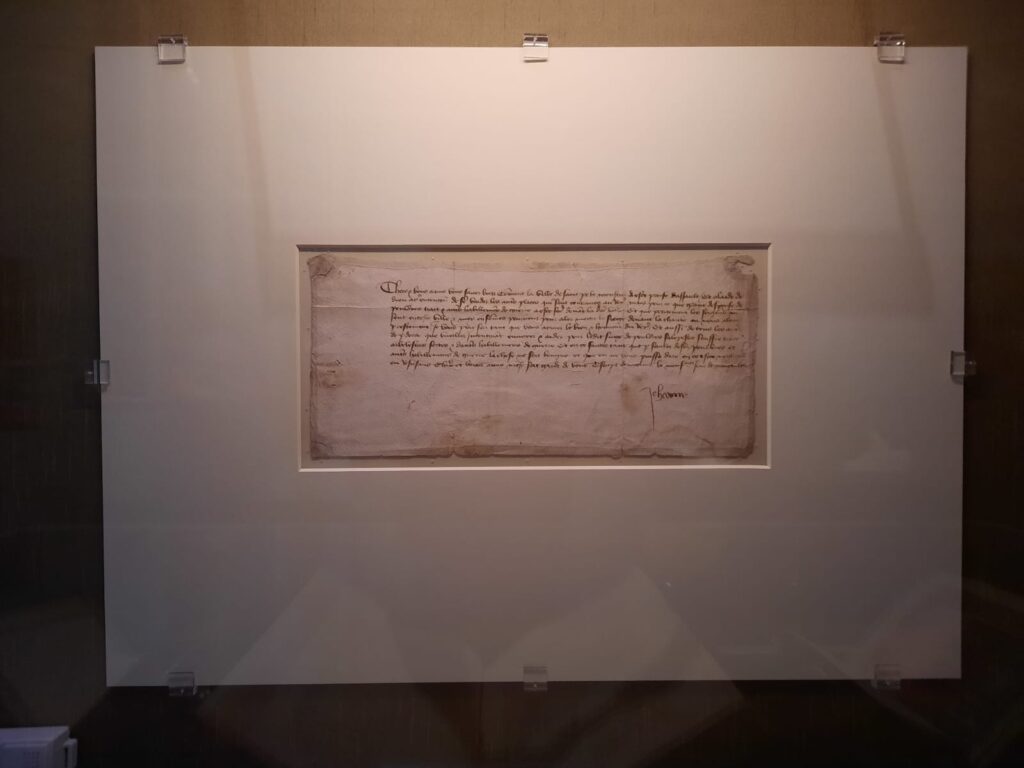

A second category of exhibits are those which are almost women’s own words, but were never in their own hand. Because of low literacy levels, some of the women dictated their words to men who committed them to parchment. For instance Margery of Kempe, whose second attempt at dictating her autobiography was to an ‘extremely reluctant priest’. Or the correspondence of the Paston family of Norfolk, a remarkable survival of letters between family and friends, the women’s contributions dictated to scribes. How might this filtering through men have altered the women’s words from what they might have written themselves? If we contrast with the poetry of the absolutely extraordinary 18th century Welsh poet Gwerful Mechain, could you imagine a man taking dictation of the following?

“A girl’s thick glade,

Gwerful Mechain, ‘Poem to the Vagina’, translated by Katie Gramich (2005).

it is full of love,

Lovely bush, blessed

be it by God above.”

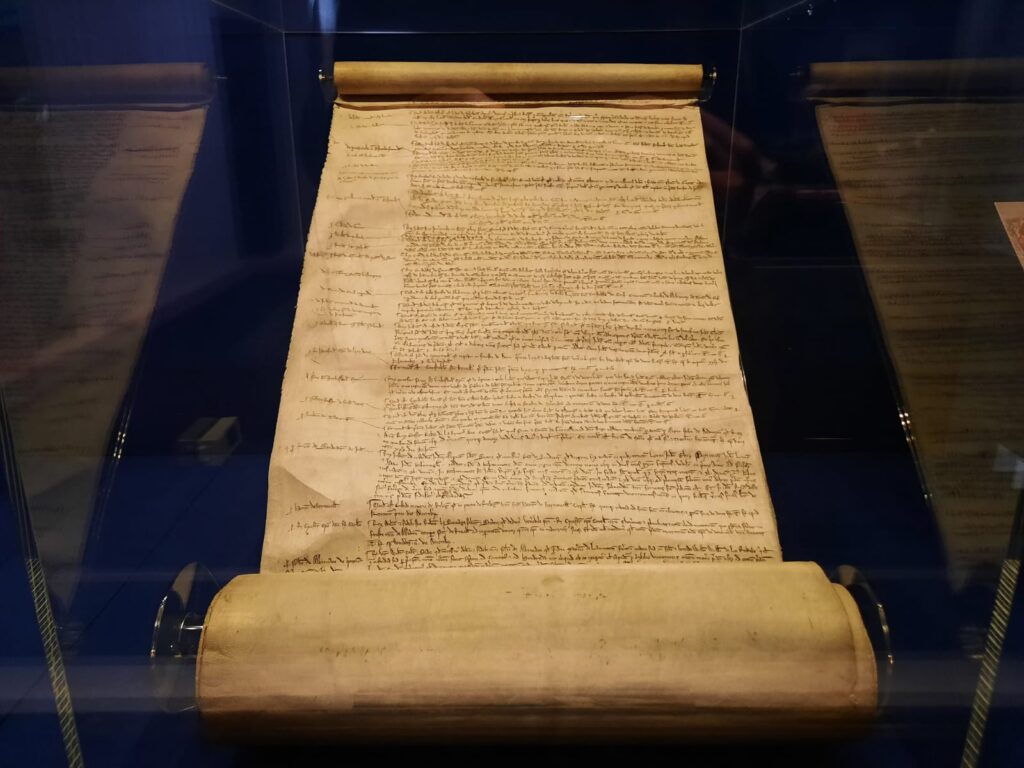

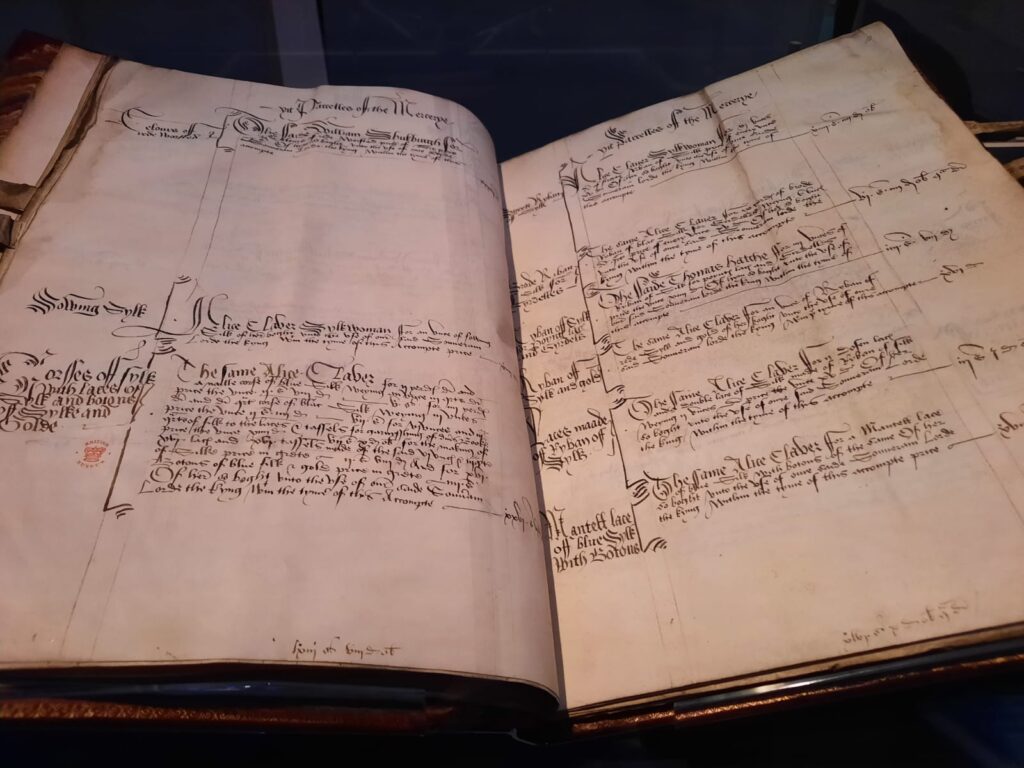

And the third category of exhibits are those which are about women. This is done, I think, to round out the exhibition. Very occasionally, for instance, a working class woman might be quoted in court documents. But otherwise very few voices of ordinary women have survived. Even fewer if you want to include intersectionally marginalised women like women of colour or Jewish women. And so there are a few things on display like records of farm workers’ wages, or a certificate of sale of an enslaved woman, or records of debts owed to women. These women’s own words may not be remembered, but traces of them remain, and that’s also important.

Bringing Archival and Printed Materials to Life

It’s not the first time I’ve made this point, but I appreciate how the British Library always make an effort in their exhibitions to bring things to life. Because, although I am a historian and a museologist, even I sometimes find exhibitions of archival and printed materials to be a bit… dull after a while. Don’t shoot the messenger, I’m just being honest! And it never stops me going to see said exhibitions.

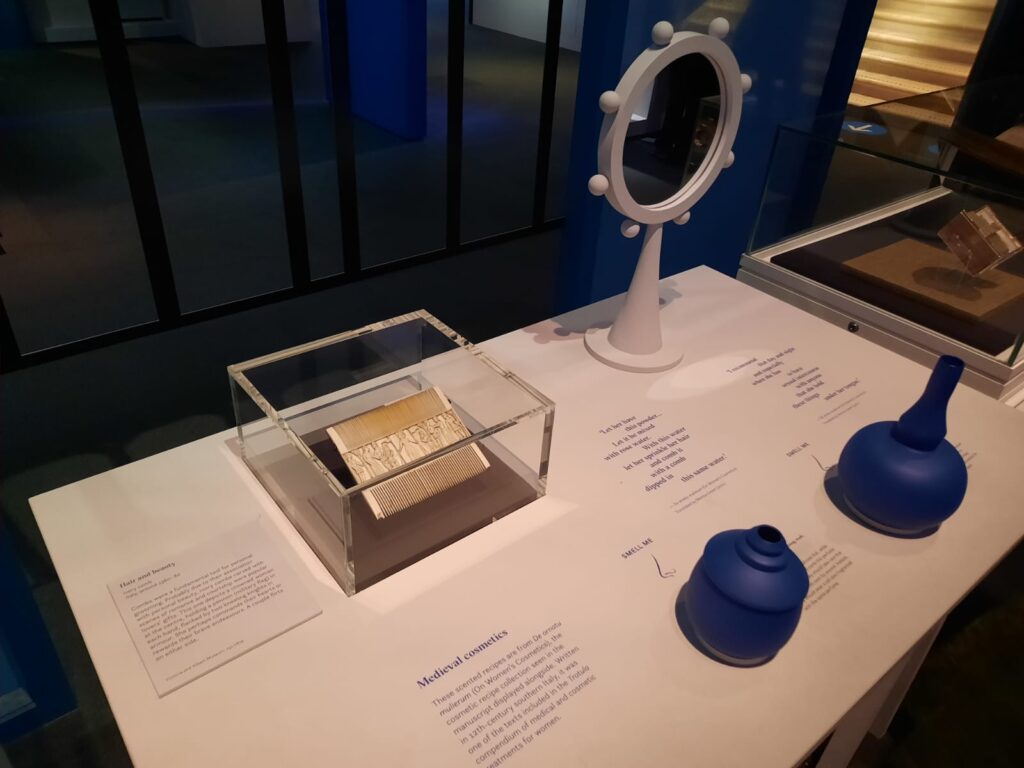

In Medieval Women, they do this in a few ways. Firstly, the exhibition design itself is nice. The different spheres of private, public and religious are enclosed within dividers that look like medieval buildings. It makes for an easy path to follow, and looks interesting. Secondly, there’s the selection of objects to exhibit. While the majority of works on view are letters, manuscripts and books, these are broken up where possible with paintings, objects or sculptures. It makes things more visually interesting.

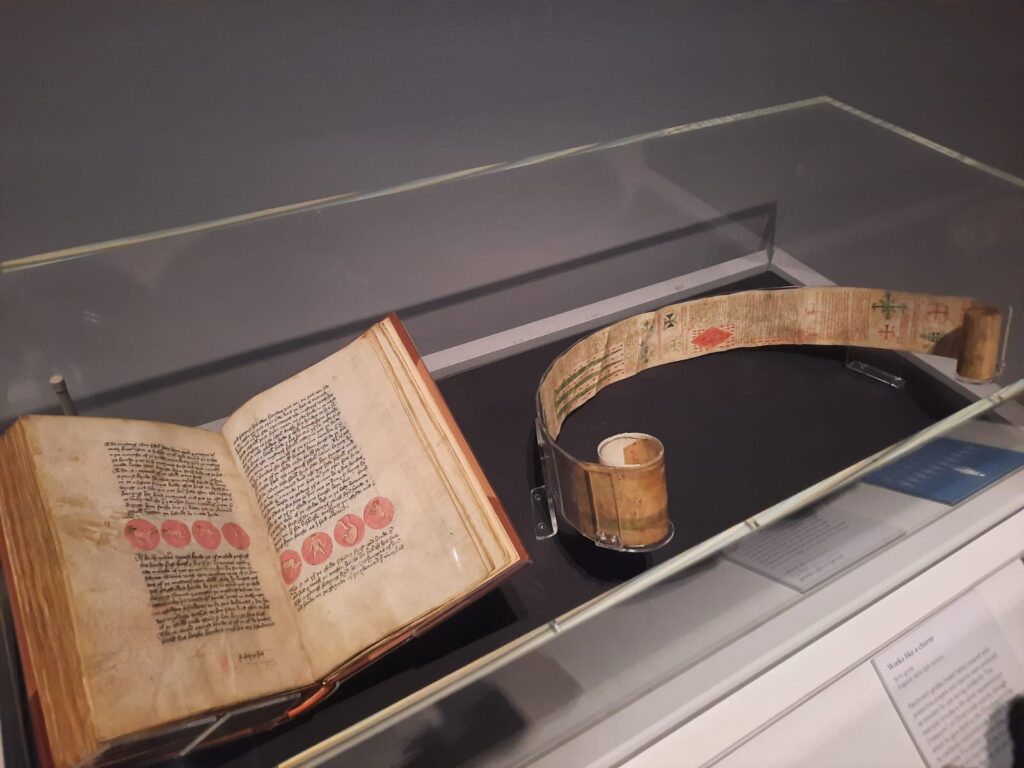

Next, there are the text panels accompanying the exhibits. In many places, they pull out key details or statistics. For instance, I might see that 82% of contracts for enslaved people in Venice between 1360 and 1499 were for women, and wander over to see what type of document would tell us that information. The texts help make sense at a glance of what are essentially bits of paper with hard-to-decipher medieval handwriting. I didn’t figure out, though, why some text panels were in gold and clearly meant to denote something specific. Then there are the videos, including ones on the remains of plague victims or anchoresses.

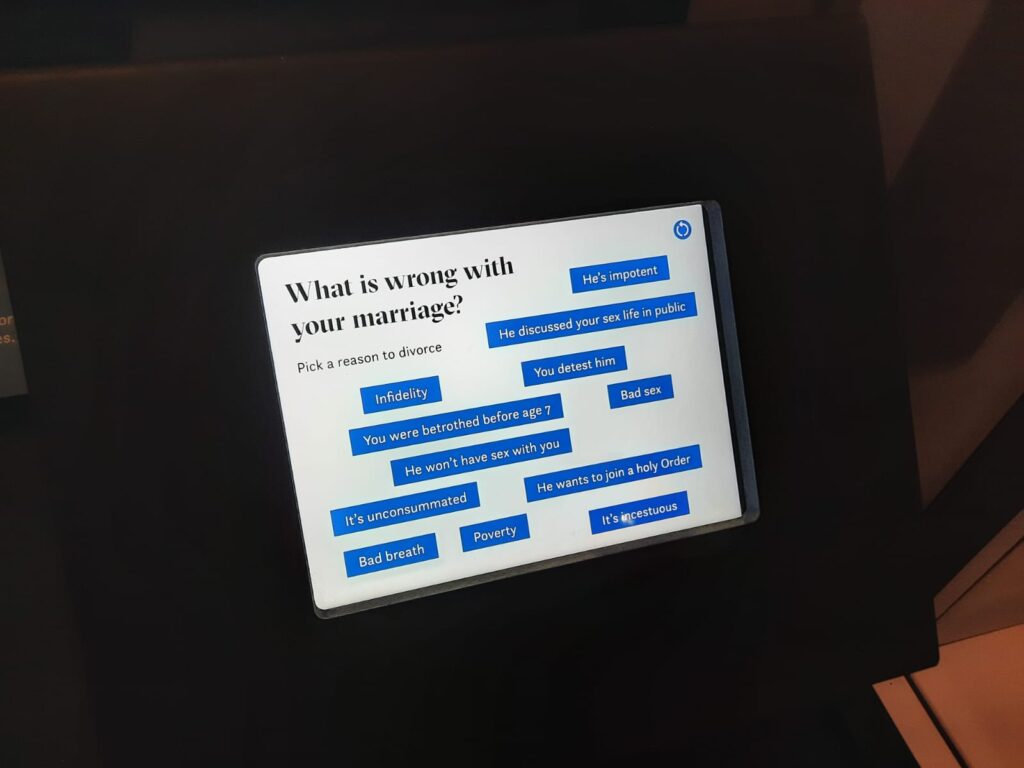

But I’m saving the best for last. The interactive tablets are a lot of fun. You can guess valid reasons for divorce on one. Bad breath? Poverty? You hate him? Click and see! Or are you a witch? Here’s a hint: don’t let anyone know about your box of bewitched penis pets, that’s a very suspicious sign of witchcraft. Lastly there are a few multisensory exhibits, including the smell of heaven and hell (or the Devil and angels) based on women’s visions. A lot of thought has gone into how to make the exhibition fun and engaging.

Final Thoughts on Medieval Women: In Their Own Words

Thinking about the exhibition as a whole, I don’t think it challenged any of my expectations. Is that a bad thing? Maybe not. Because my expectations were that women participated in many areas of medieval life. Some more actively than others – religious life being one way for women to have more agency and access to learning than your typical medieval women. But that the historic record overwhelmingly favours men, especially when it comes to first hand accounts.

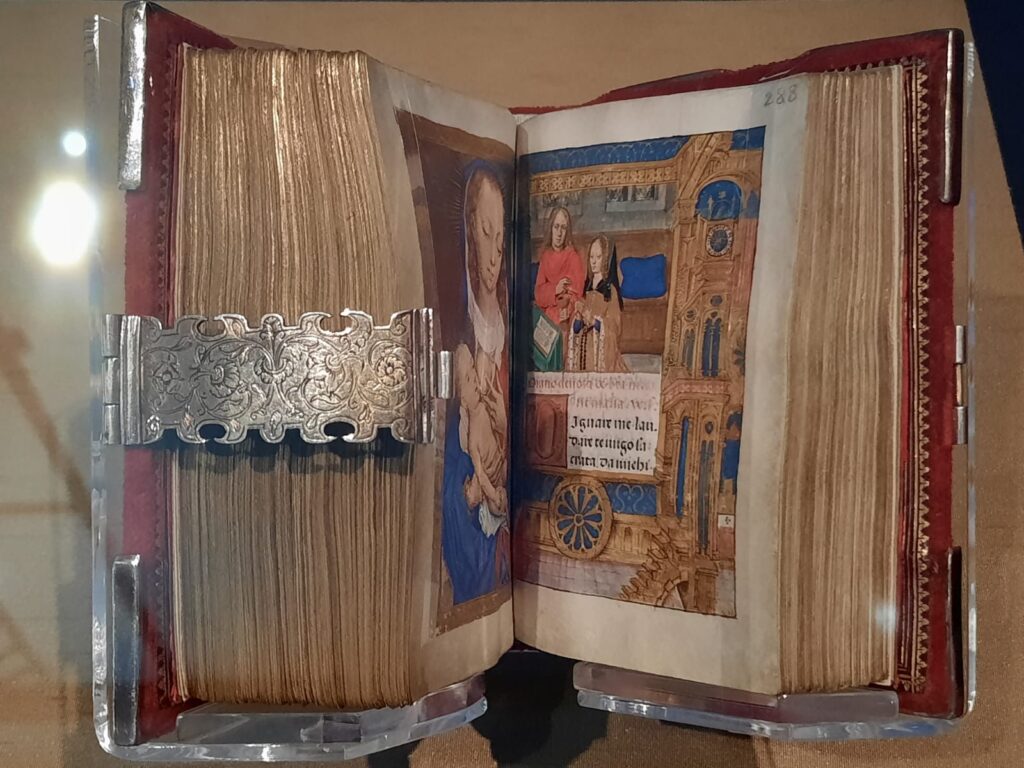

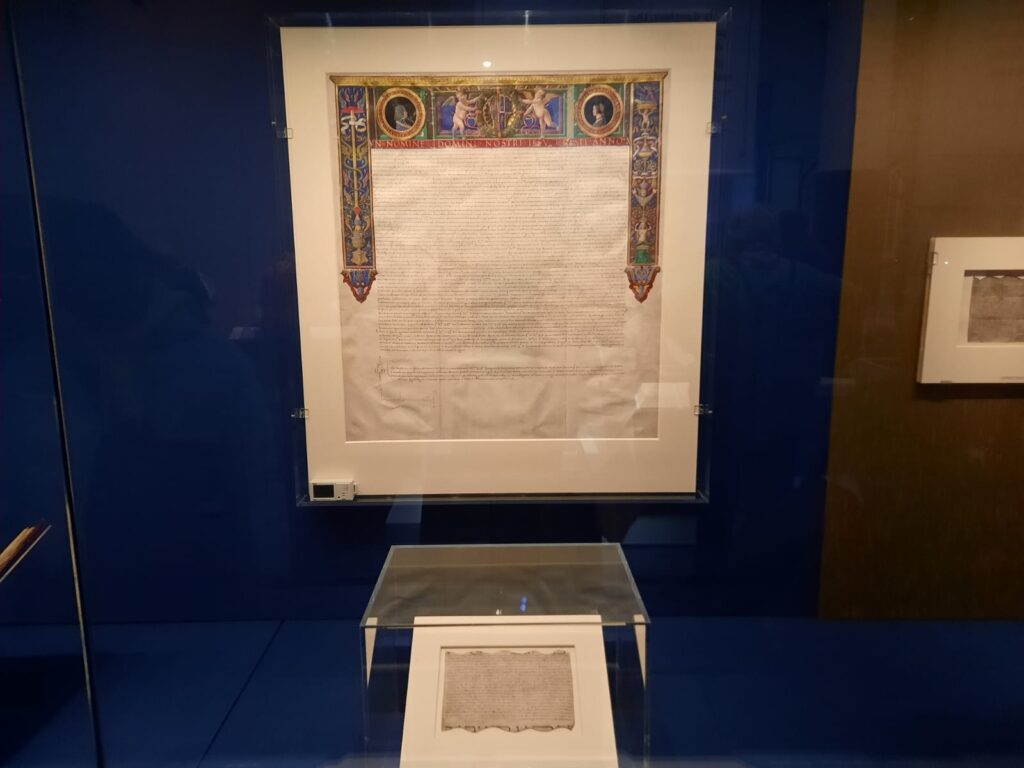

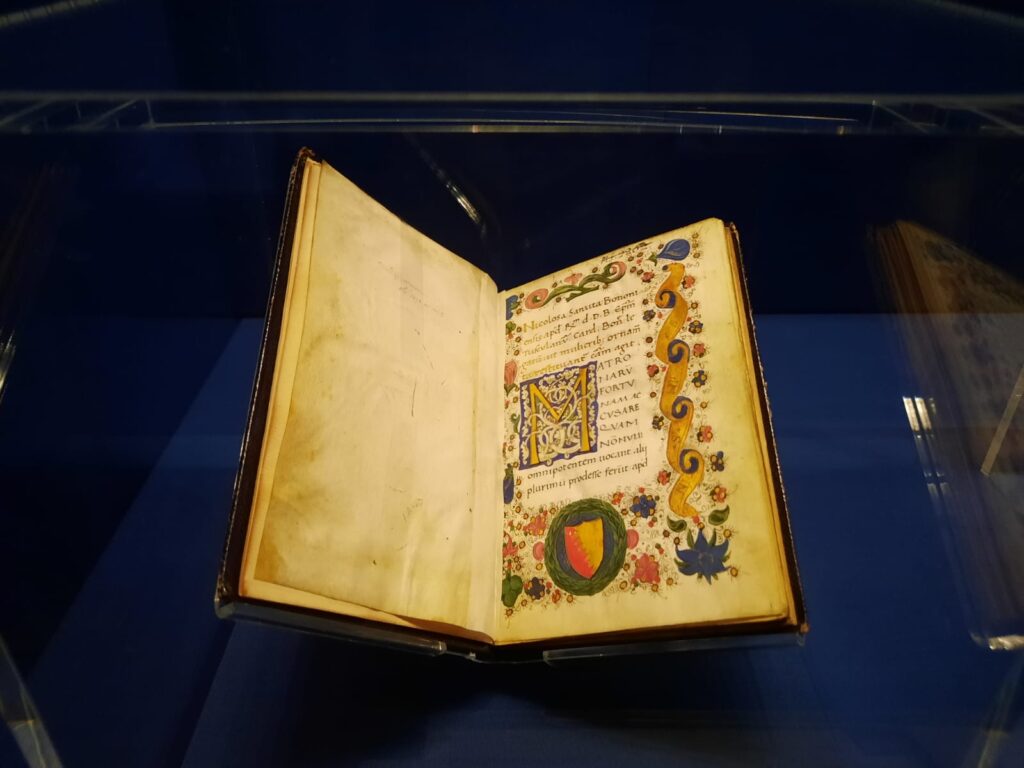

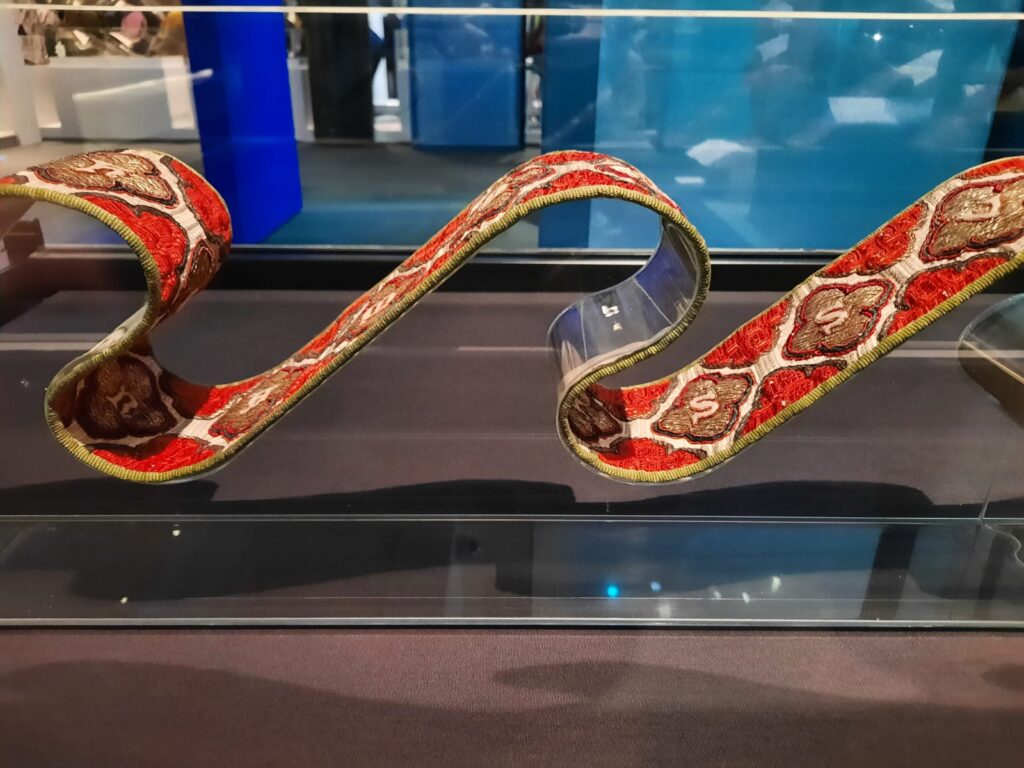

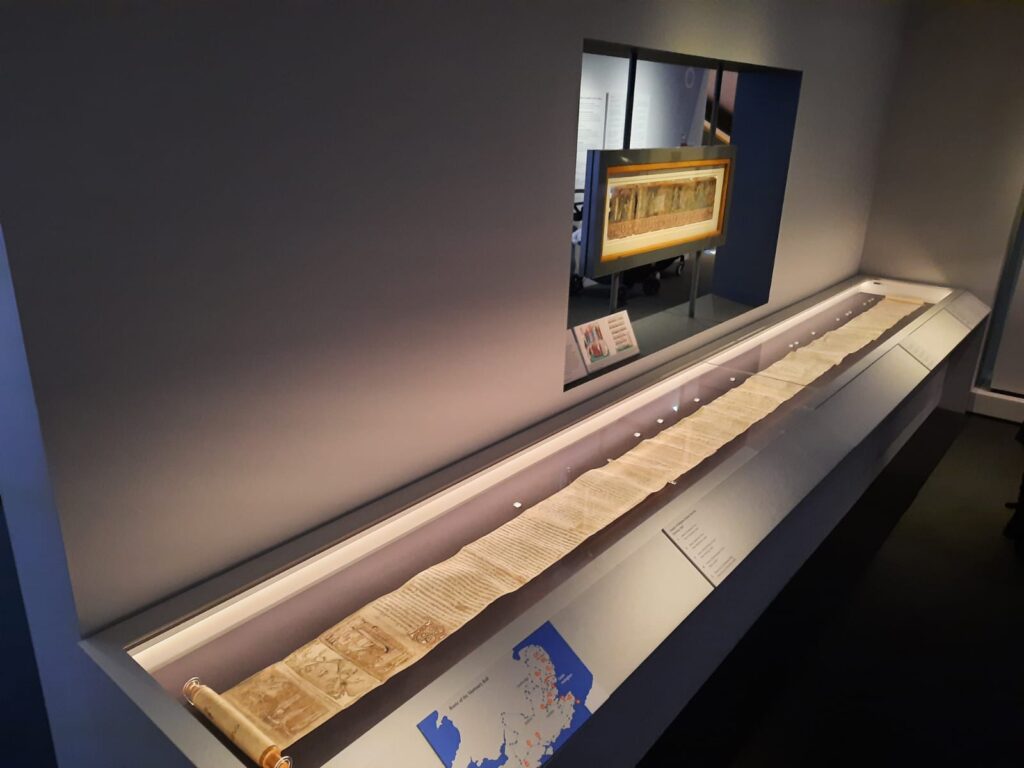

That was borne out by the exhibition. It’s telling, for instance, that there aren’t enough examples of women in their own words for that to be the basis of the whole exhibition. There are things written by women, spoken (ie. dictated) by women, and about women. It’s nonetheless very interesting. I learned the names and stories of more medieval women than I knew before. I saw beautiful illuminated manuscripts, and unusual objects like a superstitious parchment belt for women giving birth. Plus I saw Joan of Arc’s signature (she was one of the ones dictating messages), which is pretty cool.

One thing which may or may not be a shame is how many women were there when I visited. It’s great on the one hand for women to learn about this topic and see interesting women from history. But isn’t is also great for men to do the same? It’s not that there were no men, to be fair. Just a generous gender bias.

The exhibition is on for a few more weeks. I encourage my readers of all genders to go and take a look. Between this and the other exhibition on the Silk Road, there are the makings of an educational and interesting day out at the British Library.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Medieval Women: In Their Own Words on until 2 March 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.