Silk Roads – British Museum, London

The Silk Road (or Roads) is an interesting topic which seems to speak to the current Zeitgeist. But unless you love being part of a long queue, you’re better off reading the catalogue than coming to the British Museum.

Silk Roads: Part of the Zeitgeist?

Back in November I shared my experience of seeing A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang at the British Library. I commented at the time that it was one of two exhibitions in London on very similar topics, and wondered what that meant.

I’ve had some time in the interim to think about this further. And I think there are a couple of interrelated points to make. First, let’s think about what sort of images the Silk Road (or Silk Roads) conjure up. Something about trade. Probably some orientalising visions of camels and colourful bazaars and sly merchants. A meeting point of East and West. Am I close to what you see in your mind’s eye?

And then let’s think about the present day. Very uneasy geopolitics between Europe, the US, China, Russia, the Middle East. The retraction of globalisation as many countries move back towards protectionism. Tariffs have certainly been in the headlines recently as one control over trade across borders. International travel and intercultural exchange are likewise becoming a bit more difficult.

Is it any wonder, then, that another model of international interdependency, trade and relations is of interest? Are there things we can learn from this aspect of history? Will it make anyone feel more connected, knowing how far back in time that connection reaches? Does it change any perspectives on nationalism, seeing how profoundly different cultures and religions have influenced one another?

Maybe I’m off base here, and it’s something else entirely. Or just coincidence. But my little theory does align fairly well with this quote from the exhibition catalogue:

“…encounters with various peoples active on the Silk Roads, from seafarers to Sogdians, Aksumites and Vikings, reveal the human stories, innovations and transfers of knowledge that emerged, shaping cultures and histories across continents, centuries before the formation of today’s globalised world.”

Silk Roads, British Museum Press 2024, inner jacket.

Why Silk Roads and Not Silk Road?

Having talked a little about why exhibitions about the Silk Road(s) are popping up at the moment, let’s look now at what this exhibition in particular is about. And here it comes down to one little ‘s’. Or the question: why Silk Roads and not Silk Road?

The thing we need to understand here is that the Silk Road is a construct. It’s not a real thing. Nobody was loading up their camels and saying to the wife “OK I’ll be back in three years, just going down the Silk Road to drop off this lot.” The idea of the Silk Road is a simplification of an immense network of trade routes, where goods would change hands as many times as necessary before reaching consumers. Some bits were more arduous than others, and involved crossing deserts, for instance. But it wasn’t just silk, it wasn’t one route, and it wasn’t only East/West, either. The Silk Roads (because knowing how many there were, we now add the ‘s’) connected people in modern-day China, Korea, Indonesia, Ghana, Egypt, Iraq, Türkiye, Italy, Sweden, the UK, and many more places besides.

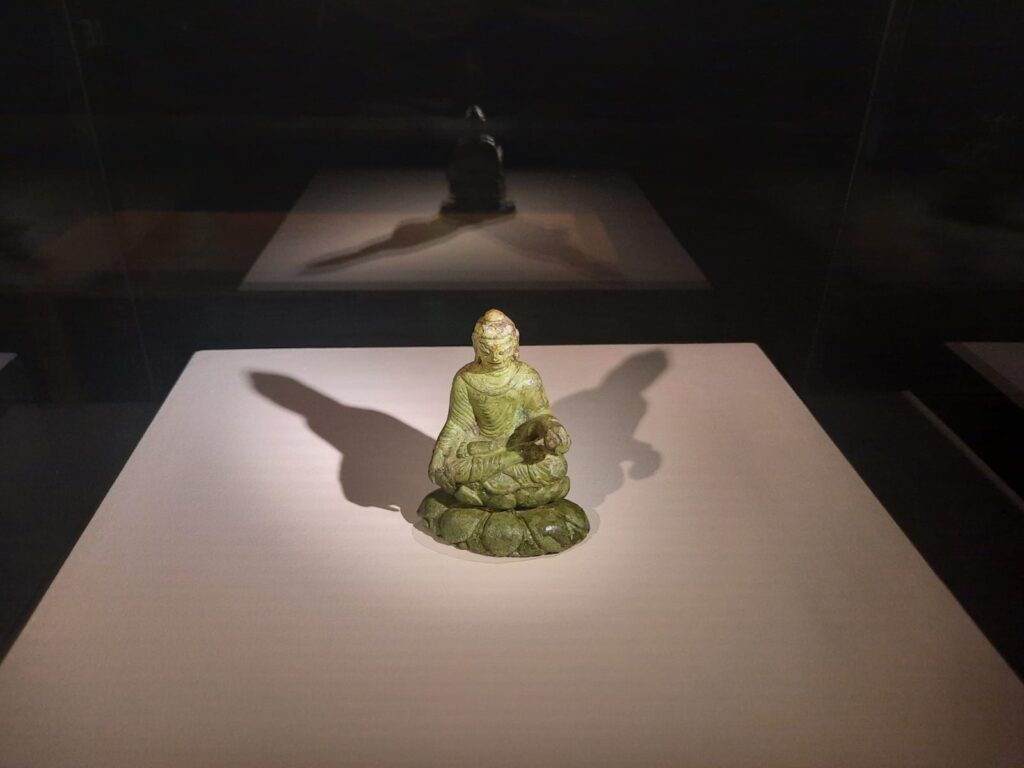

It’s a shorthand, really, for that sometimes surprising trade between civilisations we might not otherwise connect. It’s no coincidence that the exhibition opens with a spotlight on a tiny bronze Buddha from the 500-600s, likely made in what’s now Pakistan and found in a burial in Sweden. The shorthand is a 19th century invention. There’s some debate, but it’s normally attributed to geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen. So originally the Silk Roads were Seidenstrasse. And as I mentioned in my last post on the subject, the term was popularised at least in part by Sven Hedin (a defender of Nazi Germany, boo).

The British Museum, then, aim to expand our horizons once more. From a single strand of silk connecting East and West back to a complex and intricate network, like a beautiful textile connecting most parts of what was then the ‘known world’. What a fascinating subject to investigate!

Silk Roads? More Like Silk Traffic Jams…

The last time I had a real moan about overcrowding in an exhibition it was one of my most successful posts in a while. So get ready, lovers of complaints and first world problems!

I found the experience of visiting Silk Roads absolutely horrendous. So much so that the Urban Geographer and I raced through in record speed and bought the catalogue so we could find out what we missed. Like the National Gallery, British Museum exhibitions are normally busy. As I’ve commented before, there is a science to both designing exhibitions and knowing how many people they will comfortably hold, so at some point I have to assume it’s either willful or reflects some dire financial situation. Unless they are really surprised every time at how busy it is…?

I have seen enough other reviews to know that I wasn’t the only one. And the first of two points that I would like to make here is something I’ve seen echoed elsewhere. That being – the whole thing was a traffic jam. Why is that? Let me tell you my thoughts:

- There is one long snaking route from start to finish. Contrast this with Hew Locke: what have we here? which I visited on the same day in the same museum. This exhibition was deliberately not linear, meaning although it was busy everyone could move around freely to unoccupied exhibits. Here I skipped entire display cases because I couldn’t face the slow-moving queues.

- The queues were very slow because you had to read most of the text at the same time. This is something that (in my opinion) they could have planned a bit better. Mount more texts on walls. Hand out a guide with some of the texts on it. Have an app. But when the texts are all at display case or person height, you have to stand in front of each exhibit reading and looking. Particularly when the museum is a major tourist attraction in its own right and so has a lot of visitors for whom English isn’t their first language. Even the introductory texts were often out of sight behind queuing visitors.

There was something I found a little ironic here. The thesis of the exhibition is that the Silk Roads were a matrix rather than one route. Isn’t there some way the exhibition could have been more of a matrix rather than… one route?

A Trade Route? Or a Trade Fair?

The other thing I would like to complain about (and am allowed to because this is my personal blog – you can choose whether or not to read but you can’t stop me) is that it felt at times more like a trade fair than an exhibition. I work in an industry where I go to a fair number of conferences, and Silk Roads felt a lot like a vendor exhibition rather than a museum exhibition. Maybe it’s that I find both an assault on the senses, but there was also something about the exhibition design that made this connection for me.

Silk Roads is organised broadly East to West. Signs overhead name different cities and trading posts, like Dunhuang, Samarkand, Chang’an, Damascus, Aachen or Sutton Hoo. What I might call the fringes of the Silk Roads are in curtained bays. These are topics like maritime trade or Vikings. Occasionally there are videos projected onto the walls, mostly scenes of nature. Compared to other exhibitions I’ve seen in the same exhibition space, it seemed really open, like a big hangar. I’m telling you, it is really strongly reminiscent of an IT conference. And more specifically, the space with all the vendor stalls. Everyone trying to entice you and clamouring for attention. Only here, it’s somehow the same exhibition competing with itself.

I’m not saying I think orientalising is a good thing – it’s patently reductionist and othering. But – and hear me out – if the experience of Silk Roads had been a little like a bazaar, that would be one thing. Maybe leaning into stereotypes a bit, but at least a captivating experience. And there are things that would make sense in that context, like exhibits where you lift a flap to smell an exotic scent. Plus the thing about a bazaar is that you can go where your fancy takes you, it’s not an IKEA where you’re trapped following one route. But I don’t think anyone could have been aiming to recreate the atmosphere of a vendor showcase at an IT conference. This has got to be an unintended consequence.

Bringing Disparate Strands Together

This has been a review of two halves. I spent the first two sections setting out the purpose of the exhibition and pondering why it is that the Silk Road(s) are on everyone’s mind at the moment. Then I went off on a rant based on my experience visiting the exhibition. How do we now bring these disparate strands back together, or at least into some sort of connection with each other?

I think one important thing to note is that we tend to have the biggest reactions when high expectations haven’t been met. I’ve experienced busy exhibitions before at the British Museum, sure. And some of them have had the same pitfalls, like displays of little objects and accompanying texts that you can’t help but crowd around. But I’ve never given up to such an extent before, and just picked up a catalogue instead.

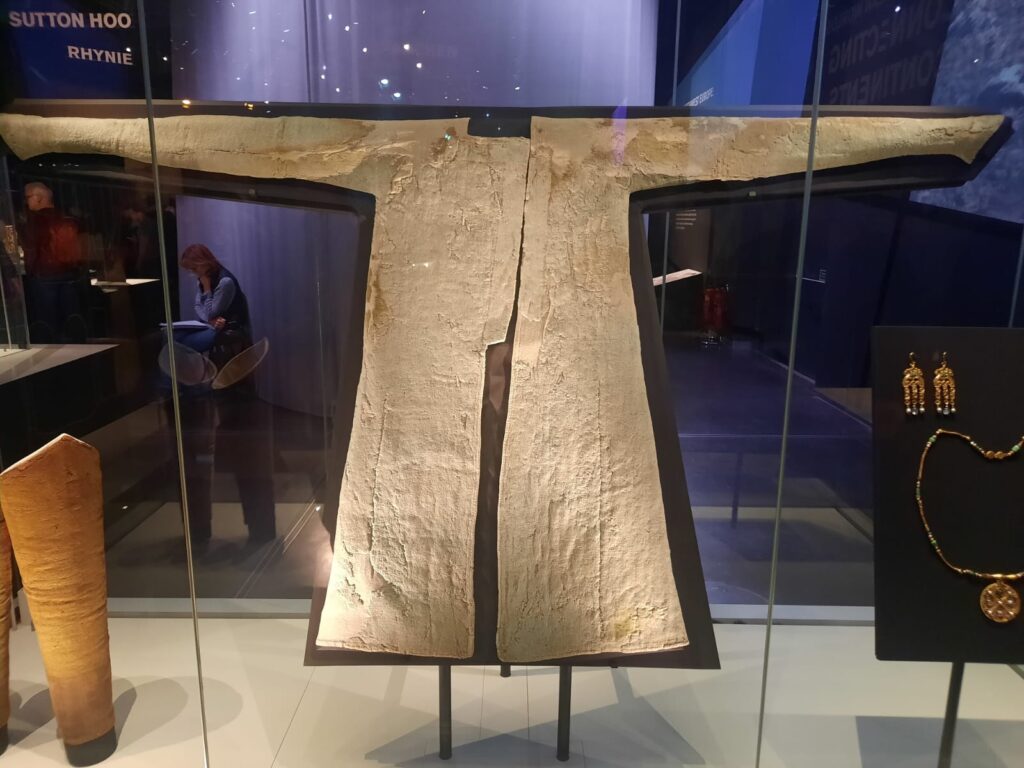

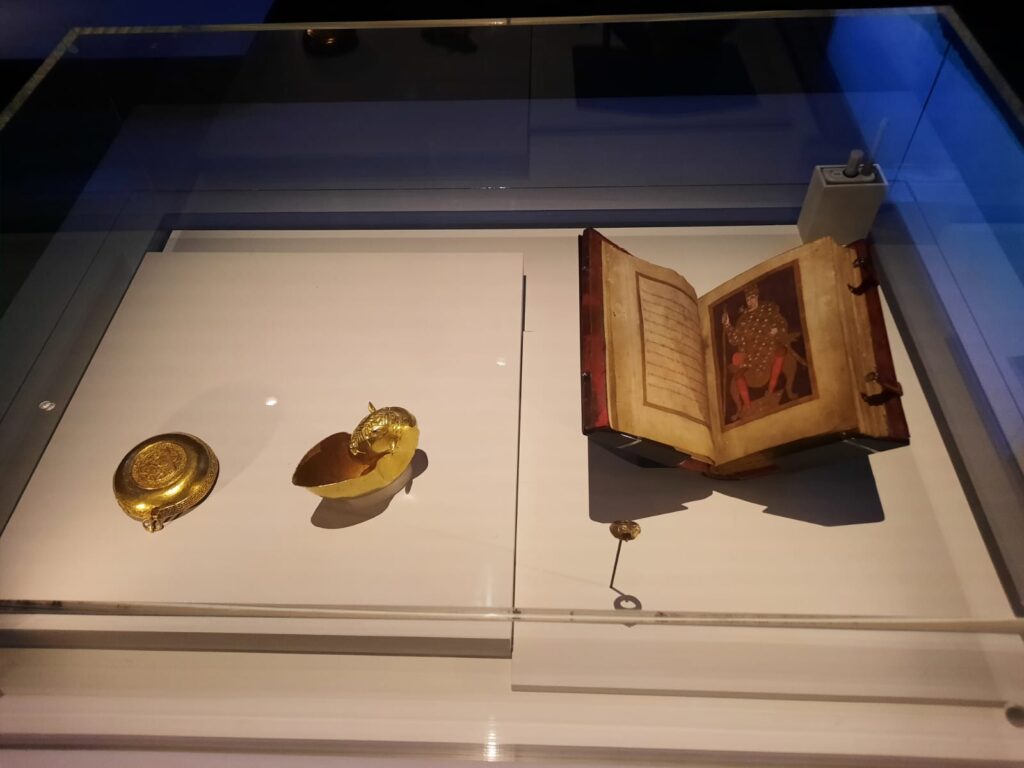

Part of my disappointment was that I felt like there was a really fascinating exhibition underneath it all, which I couldn’t get to because of the crowding. I love archaeological finds, remarkable textile survivals, indications of cross cultural contact like that little Buddha or the Franks Casket. At some point during my university days I studied the Franks Casket, actually, so I was pleased to see it there. I am always the first to have a go at exhibits you can sniff or interact with in different ways. It was a shame not to get up close to all these cool objects.

Is there a lesson here? I hope it’s not that those who don’t complain about the exhibitions get the press invites and get to go to nice, calm press openings. It could be that the Silk Roads are never quite what you think they are. They’re not neat and orderly. They’re messy and complex and sometimes inconvenient. Taking it a step further, does that mean they are or aren’t a model for today’s complex world? Or is the lesson that history does repeat itself, we’re all interconnected, but we always find new ways to make things complicated. If only I’d seen the exhibition properly, maybe I would have found out!

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5 for the exhibition, 2/5 taking experience into account

Silk Roads on until 23 February 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.